Central Bureau of Investigation: India

(→General consent for investigating cases in a state) |

(→CBI investigations: who can order?) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

| + | ==How the CBI takes up cases== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-how-the-cbi-investigates-birbhum-bengal-killings-7836684/?utm_source=newzmate&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=explained&utm_content=6386461&pnespid=AeYyqlpE5HxMjlmfusiMR1FbsQM_m7xtsQ9NA79fOYLKmzWVLELTrmjZbWQkX921Tq7vzS_2 Deeptiman Tiwary, March 26, 2022: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' How does the CBI take up cases? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unlike the NIA, CBI cannot take suo motu cognizance of a case in a state — whether in a matter of corruption involving government officials of the Centre and PSU staff, or an incident of violent crime. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In order to take up corruption cases involving central government staff, it either needs general consent (see last question) of the state government, or specific consent on a case-to-case basis. For all other cases, whether involving corruption in the state government or an incident of crime, the state has to request an investigation by the CBI, and the Centre has to agree to the same. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In case the state does not make such a request, the CBI can take over a case based on the orders of the High Court concerned or the Supreme Court. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Can the CBI decline to take up a case for investigation? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | After a state makes a request for an inquiry by the CBI, the Centre seeks the opinion of the agency. If the CBI feels that it is not worthwhile for it to expend time and energy on the case, it may decline to take it up. In the past, the CBI has refused to take over cases citing lack of enough personnel to investigate, and saying it is overburdened. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2015, the agency had told the Supreme Court that it could not take any more Vyapam scam cases because it did not have enough staff to investigate them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “CBI is the country’s premier investigation agency, and it is expected to probe complex and sensitive cases. It cannot probe every case that a state is willing to hand over to it,” a CBI officer said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to a former CBI officer, in nine out of 10 instances, the Centre seeks the opinion of the agency before accepting or refusing a case. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “In 10% of cases, the Centre directly orders the registering of a case if it suits the ruling dispensation to do so. Once, in a Northeastern state, an additional chief secretary was beaten up and the state government wanted the CBI to investigate. The agency, after a preliminary probe, refused to accept the case on the ground that it was too small an incident for the CBI to get involved, and that the state police were fully capable of carrying out the probe,” the officer said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' What is the CBI’s workload currently? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the latest Annual Report of the Central Vigilance Commission, the CBI registered 608 FIRs in 2019 and 589 FIRs in 2020. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2020, a total 86 cases related to demands for bribes by public servants for showing favour, and 30 cases for possession of disproportionate assets were registered. | ||

| + | Out of 676 cases in the year (including FIRs and Preliminary Enquiries), 107 cases were taken up on the directions of constitutional courts and 39 on requests from state governments/ Union Territories. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are over 1,300 vacancies in the CBI. As on December 31, 2020, against a sanctioned strength of 7,273, only 5,899 officials were in position, and 1,374 posts were lying vacant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' What is the CBI’s progress on cases? ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the end of 2020, the CBI had 1,117 cases (both FIRs and PEs) pending investigation. In 2019, this number stood at 1,239. During 2020, investigation was finalised in 693 FIRs and 105 PEs. As many as 637 cases were pending for investigation for more than one year as on December 31, 2020. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The conviction rate during the year was 69.83% against 69.19% in 2019. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At the end of 2020, 9,757 cases were pending in various courts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The conviction rate in corruption cases was slightly lower at 67% in 2020. In 2020, CBI registered 425 cases of corruption involving 565 government officials. It completed investigations in 429 cases (including those from previous years). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 191 cases, trials were completed, of which 128 ended in conviction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, of the 655 people who stood trial in CBI cases during the year, only 260 were convicted — meaning 60% of accused were either acquitted or discharged. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Until December 31, 2020, as many as 6,497 corruption cases were pending trial in various courts. Of these, 5,193 cases (80%) had been pending for more than three years. Almost 2,000 corruption cases are pending trial for more than 10 years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Government|C | ||

| + | CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:India|CCENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIACENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIACENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIACENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIA | [[Category:India|CCENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIACENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIACENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIACENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIA | ||

CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIA]] | CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION: INDIA]] | ||

Revision as of 19:18, 27 March 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Autonomy

SC’s 2019 verdict

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Don’t interfere with CBI autonomy: SC, January 9, 2019: The Times of India

Five years after CBI earned the ‘caged parrot’ moniker over its then director going to the political executive for vetting a coal scam probe status report meant only for the Supreme Court, the apex court on Tuesday said Parliament always intended to insulate the agency from external influences.

Quashing the Centre’s October 23 order divesting director Alok Verma of all powers, SC warned all authorities to keep away from “interfering in the functioning of the CBI director”. However, it said: “In a situation where such interference may be called for, public interest must be writ large against the backdrop of necessity”. However, it clarified that such a necessity could only be tested by the Selection Committee comprising the PM, Leader of Opposition and CJI or his nominee.

A bench of CJI Ranjan Gogoi and Justices S K Kaul and K M Joseph said the stipulation in the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act that the CBI director cannot be transferred except with the prior consent of the Selection Committee would convey that the panel’s prior consent is mandatory not only for transfer but also for any action amounting to tinkering with the two-year fixed tenure of the CBI chief.

The CJI said if prior consent of the panel was confined only to transfer, such an interpretation would “clearly negate legislative intent” and would make it easy for the government “to effectively disengage the CBI director from functioning by adopting various modes... which may not amount to transfer but would still have the same effect as a transfer from one post to another, namely, cessation of exercise of powers and functions of the earlier post”.

After an in-depth consideration of the development of legislation in the light of SC judgments, the CJI-led bench said: “(It) leaves us with no doubt the clear legislative intent in bringing the aforesaid provisions to the statute book are for the purpose of ensuring complete insulation of the office of the CBI director from all kinds of extraneous influences, as may be, as well as for upholding the integrity and independence of the institution of the CBI as a whole.”

SC added that “the head of the institution.. therefore, has to be the role model of independence and integrity, which can only be ensured by freedom from all kinds of control... except to the extent that Parliament may have intended. (That) would require all authorities to keep away from intermingling or interfering in” the chief ’s role.

CBI investigations: who can order?

HC can order CBI probe

From the archives of The Times of India 2010

HC can order CBI probe: SC

Swati Deshpande | TNN

Mumbai: A five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court headed by the Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan, on Wednesday adjudged that the country’s high courts can order a CBI probe into a case without the assent of a state government, while also cautioning that such powers should be used sparingly, and only in matters of national or international importance.

The SC was hearing the West Bengal government’s petition challenging the Calcutta high court order of a CBI probe into the Midnapore firing in which 14 Trinamool Congres workers were killed. The WB government argued that law and order was a state subject and that a CBI probe without the state’s nod would be a ‘‘destruction of the federal character of the Constitution’’. West Bengal was the main petitioner along with some southern states.

But, taking a stand based on the ‘‘higher principle of constitutional law’’, attorney general Goolam Vahanvati argued that the powers of the high courts and the Supreme Court under Articles 226 and 32 were coupled with a strong obligation to prevent injustice in sensitive cases and to protect the fundamental rights of citizens. The SC bench agreed with him, and dismissed the petition. Until now, the CBI conducted probe in any state only with prior consent of the concerned government under the provisions of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act.

The five-judge Constitution Bench headed by Chief Justice K G Balakrishnan and Justices R V Raveendran, D K Jain, P Sathasivam and J M Panchal agreed unanimously with Vahanvati but said the power must be exercised sparingly in ‘‘exceptional and extraordinary circumstances.’’ Otherwise, the CBI will be flooded with such directions in routine cases, the bench said.

How the CBI takes up cases

Deeptiman Tiwary, March 26, 2022: The Indian Express

How does the CBI take up cases?

Unlike the NIA, CBI cannot take suo motu cognizance of a case in a state — whether in a matter of corruption involving government officials of the Centre and PSU staff, or an incident of violent crime.

In order to take up corruption cases involving central government staff, it either needs general consent (see last question) of the state government, or specific consent on a case-to-case basis. For all other cases, whether involving corruption in the state government or an incident of crime, the state has to request an investigation by the CBI, and the Centre has to agree to the same.

In case the state does not make such a request, the CBI can take over a case based on the orders of the High Court concerned or the Supreme Court.

Can the CBI decline to take up a case for investigation?

After a state makes a request for an inquiry by the CBI, the Centre seeks the opinion of the agency. If the CBI feels that it is not worthwhile for it to expend time and energy on the case, it may decline to take it up. In the past, the CBI has refused to take over cases citing lack of enough personnel to investigate, and saying it is overburdened.

In 2015, the agency had told the Supreme Court that it could not take any more Vyapam scam cases because it did not have enough staff to investigate them.

“CBI is the country’s premier investigation agency, and it is expected to probe complex and sensitive cases. It cannot probe every case that a state is willing to hand over to it,” a CBI officer said.

According to a former CBI officer, in nine out of 10 instances, the Centre seeks the opinion of the agency before accepting or refusing a case.

“In 10% of cases, the Centre directly orders the registering of a case if it suits the ruling dispensation to do so. Once, in a Northeastern state, an additional chief secretary was beaten up and the state government wanted the CBI to investigate. The agency, after a preliminary probe, refused to accept the case on the ground that it was too small an incident for the CBI to get involved, and that the state police were fully capable of carrying out the probe,” the officer said.

What is the CBI’s workload currently?

According to the latest Annual Report of the Central Vigilance Commission, the CBI registered 608 FIRs in 2019 and 589 FIRs in 2020.

In 2020, a total 86 cases related to demands for bribes by public servants for showing favour, and 30 cases for possession of disproportionate assets were registered. Out of 676 cases in the year (including FIRs and Preliminary Enquiries), 107 cases were taken up on the directions of constitutional courts and 39 on requests from state governments/ Union Territories.

There are over 1,300 vacancies in the CBI. As on December 31, 2020, against a sanctioned strength of 7,273, only 5,899 officials were in position, and 1,374 posts were lying vacant.

What is the CBI’s progress on cases?

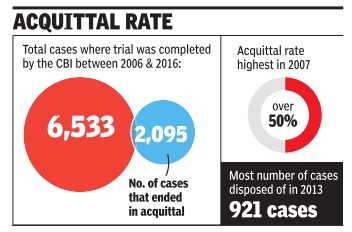

At the end of 2020, the CBI had 1,117 cases (both FIRs and PEs) pending investigation. In 2019, this number stood at 1,239. During 2020, investigation was finalised in 693 FIRs and 105 PEs. As many as 637 cases were pending for investigation for more than one year as on December 31, 2020.

The conviction rate during the year was 69.83% against 69.19% in 2019.

At the end of 2020, 9,757 cases were pending in various courts.

The conviction rate in corruption cases was slightly lower at 67% in 2020. In 2020, CBI registered 425 cases of corruption involving 565 government officials. It completed investigations in 429 cases (including those from previous years).

In 191 cases, trials were completed, of which 128 ended in conviction.

However, of the 655 people who stood trial in CBI cases during the year, only 260 were convicted — meaning 60% of accused were either acquitted or discharged.

Until December 31, 2020, as many as 6,497 corruption cases were pending trial in various courts. Of these, 5,193 cases (80%) had been pending for more than three years. Almost 2,000 corruption cases are pending trial for more than 10 years.

Controversial cases

Moin Akhtar Qureshi

Neeraj Chauhan, How one case took down three agency directors, October 25, 2018: The Times of India

After a year of squabbling between CBI director Alok Verma and special director Rakesh Asthana, both were sent on leave — and the man at the centre of the controversy once again was Moin Akhtar Qureshi, who was also behind the downfall of two CBI chiefs, A P Singh and Ranjit Sinha.

The millionaire meat exporter from Kanpur faces multiple investigations, ranging from tax evasion to money laundering and corruption. He is also accused of spending large sums through hawala transactions and other modes to oblige government officials, including CBI officers and politicians.

His name first cropped up in 2014, when it was found that he visited then CBI chief Ranjit Sinha’s residence at least 70 times in over 15 months. Hyderabad-based businessman Sathish Babu Sana, who now figures in the fight between Verma and Asthana, reportedly told the Enforcement Directorate (ED) last year that he had paid Rs 1 crore to Qureshi to get bail for his friend in a CBI case through Sinha.

The Supreme Court came down heavily on Sinha for his meeting with accused persons or suspects and he came under the CBI scanner. The allegations against Sinha revived calls for reforming CBI and more oversight in its working. Sinha, who headed the CBI from 2012 to 2014, has repeatedly denied all charges.

Later in 2014, it turned out that Qureshi had exchanged messages with another CBI director, A P Singh, who headed the agency from 2010 to 2012. The income tax department and the ED probed the matter initially and in February last year, the CBI too registered a case against Singh to probe his links with Qureshi. The allegations cost Singh his ‘member’ post in Union Public Service Commission as he had to step down. Singh too has denied all charges against him and says the CBI is yet to even contact him.

The Qureshi probe has now cost Alok Verma his job, as the government on Wednesday divested him of all his powers and duties.Asthana has alleged that Verma took Rs 2 crore bribe from Sana, a suspect, to give relief in the Qureshi case while Verma filed an FIR against Asthana last week alleging that the latter took Rs 3 crore from Sana.

Qureshi rose to become India’s biggest meat exporter after starting a small slaughterhouse in Rampur, UP, in 1993. He established more than 25 companies spreading across sectors including construction and fashion in last 25 years.

Cases against top opposition politicians

Dhananjay Mahapatra, Sep 9, 2019: The Times of India

In the last 10 years, we witnessed the CBI investigating major scams and cases, involving prominent politicians. The agency earned a ‘caged parrot’ epithet from the Supreme Court in May 2013 for allowing the UPA government to vet its probe status report to the SC in the coal scam, in which the government itself was in the dock.

When P Chidambaram was home minister, the SC in Rajendran Chingaravelu vs RK Mishra [2010

(1) SCC 457] case had disapproved the tendency of investigating agencies to subject the accused to media trial by selectively leaking unsubstantiated probe details . It had said, “There is a growing tendency among investigating officers to inform the media, even before completion of investigation, that they have caught a criminal or an offender. Such crude attempts to claim credit for imaginary investigational breakthroughs should be curbed. Premature disclosures or ‘leakage’ to media in a pending investigation will not only jeopardise and impede further investigation, but many a time, allow the real culprit to escape from law.” Chidambaram must now be experiencing the truth behind these observations as he languishes in judicial custody in the INX Media case.

Sadly, investigating agencies did not abandon their old practice following the SC judgment. In 2010, the CBI took interest in then Gujarat minister of state for home Amit Shah in the Sohrabuddin fake encounter case after the SC transferred the probe from Gujarat police to the central agency.

The CBI arrested Shah on July 25, 2010. On his arrest, Shah had said that charges against him were “fabricated, politically motivated and were on the instructions of the Congress government” at the Centre, which are exactly the same lines now parroted by Chidambaram, his son and big lawyers appearing for him.

Defending the CBI action, Congress spokesperson A M Singhvi had said, “Do you think the CBI is full of a bunch of fools who will risk their entire career by making false allegations and non-existing charges, which are going to be examined by the Supreme Court?”

The Gujarat HC granted bail to Shah on October 29, 2010. The CBI immediately rushed to the SC seeking cancellation of bail. Shah volunteered to stay away from Gujarat. The SC agreed and continued his bail with a caveat that he would mark his attendance before the CBI once every fortnight.

After filing a chargesheet on November 25, 2010, the CBI moved the SC in January 2011 seeking transfer of trial outside Gujarat, preferably to Mumbai. A bench headed by Justice Aftab Alam recorded what the CBI said in its application, “Amit Shah presided over an extortion racket. In his capacity as minister for home, he was in a position to place his henchmen, top ranking policemen at positions where they would sub-serve and safeguard his interest.”

In its September 27, 2012, order, the Justice Alam-headed bench transferred the trial to Mumbai. It rejected the CBI’s plea for cancellation of Shah’s bail with a sarcastic order, “We are not inclined to cancel the bail granted to Amit Shah about two years ago. Had it been an application for grant of bail to Amit Shah, it is hard to say what view the court might have taken.”

However, the SC clarified that whether Shah was to be sent to jail in “judicial custody or granted bail” in the Tulsiram Prajapati fake encounter case would be decided without taking into account grant of bail in the Sohrabuddin case.

The CBI had filed a separate FIR in the Tulsiram Prajapati case after strenuously claiming before the SC that Prajapati’s murder was part and parcel of the Sohrabuddin encounter case. Tee SC rejected it and quashed the separate FIR in Prajapati case. A Mumbai trial court discharged Shah from the Sohrabuddin-Prajapati case in December 2014.

In five years, the tables appear to have turned and the same CBI is now going after then home minister Chidambaram in an alleged corruption case relating to grant of foreign investment clearance to INX Media.

Judges of the SC and HCs take little time to discern merits of commoners’ anticipatory bail petitions. Strangely, when such pre-arrest bail pleas are filed by VIPs, renowned lawyers weave legal complexities, allege violation of right to life and liberty while accusing probe agencies of wreaking political vendetta.

Judicial treatment to anticipatory bail plea of Chidambaram is a classic example of this. A Delhi HC judge heard arguments for anticipatory bail for days and reserved judgment in January while protecting Chidambaram from arrest. He took six months to analyse the arguments and rule that Chidambaram did not deserve protection from arrest.

Senior lawyers moved the SC immediately. It was mentioned for urgent hearing before the CJI, who through court officials suggested mentioning before Justice N V Ramana the next day.

On August 21 morning, Justice Ramana ordered that the petition be placed before the CJI for orders on listing. Hours later, the matter was mentioned again before Justice Ramana, who was informed by court officials that defects in the petition were cured a few minutes before 2 pm and hence could not be listed. In the evening, the CJI ordered it to be listed on August 23. The CBI arrested him on August 21, not without enacting a drama before TV cameras.

The counsel cried foul accusing the SC of not giving importance to Chidambaram’s apprehension of his right to liberty being violated by refusing to hear his plea on August 22. A bench headed by Justice R Banumathi gave more than adequate time to lawyers who argued an anticipatory bail plea for four days. Other bail-seeking litigants would be a lot satisfied if the SC granted them a fraction of the time it spent on Chidambaram’s plea.

Yet, it was the CBI which found itself in the dock. It took a lot of accusations in the SC and outside from Congress, whose government was instrumental in getting it the “caged parrot” moniker.

Regimes will come and go. Political vindictiveness will continue to play out. But investigating agencies would do well to read Joginder Kumar vs State of UP [(1994) 4 SCC 260], in which the SC had said, “No arrest can be made because it is lawful for the police officer to do so. The existence of the power to arrest is one thing. The justification for the exercise of it is quite another.

“The law of arrest is one of balancing individual rights, liberties and privileges, on the one hand, and individual duties, obligations; weighing and balancing the rights, liberties and privileges of single individual and those of individuals collectively; of simply deciding what is wanted and where to put the weight and the emphasis; of deciding what comes first - the criminal or society, the law violator or the abider.”

Directors of CBI

2017-2018/9...: Alok Verma

Appointment of the CBI Chief, Jan 20 2017: The Times of India

Govt appoints Delhi top cop as new CBI chief

Alok Verma Gets PM & CJI's Nod, Kharge Dissents

The government has approved the appointment of Delhi Police commissioner Alok Verma as the new CBI chief in keeping with the recommendation of the selection committee.

The proceedings of the three-member collegium comprising PM Narendra Modi, Chief Justice of India J S Khehar and leader of Congress in Lok Sabha Mallikarjun Kharge, proposed the appointment by a majority decision.

Kharge gave a dissenting note, stating that the selection should be on the basis of both seniority and merit. It is understood that he had pitched for the candidature of R K Dutta, currently special secretary in the home ministry . Kharge reportedly gave his dissent note on selecting Verma citing that he had no experience of having served in CBI and he also had very little vigilance experience.

The PM and the CJI, however, felt that Verma was well suited for the job and his seniority should be taken into account.Verma will assume charge at a time when the agency is being accused by political parties of motivated probes in the context of cases against Trinamool and AAP leaders.

The decision comes ahead of the hearing in Supreme Court on Friday on a plea filed by an NGO challenging the appointment of Rakesh Asthana as acting director of the CBI after the retirement of Anil Sinha.

Official sources said Verma, a1979 batch IPS officer from the Arunachal Pradesh-Goa-Mizoram and Union Territories cadre, has been appointed CBI director for a period of two years by the Appointments Committee of Cabinet from the date he assumes office. Verma, 59, was due to retire from service in July and will now have a fixed tenure of two years. He had worked in various positions in Delhi Police, Andaman-Nicobar Islands, Puducherry , Mizoram and the Intelligence Bureau. Verma, who took charge as Delhi police chief in February last year, is likely to join in a couple of days. The CBI director's post has been lying vacant since Anil Sinha retired in the first week of December. Soon after, Asthana, a 1984 batch IPS officer from Gujarat cadre, was named interim director.

He took charge of Delhi Police from B S Bassi after relinquishing charge as director general of Tihar Jail. Verma, who will be the 27th director of CBI, has not worked in the agency before. Verma takes over at a time when the CBI is probing several crucial cases including the Rs 3,767 crore VVIP chopper scam, in which former IAF chief S P Tyagi was arrested last month. Several defence scandals, the Embraer deal, coal and 2G scams, chit fund cases, Vyapam scam, NRHM scam and non-performing assets of public sector banks are other cases being probed by the agency .

While deciding Verma's name, the collegium had also discussed the names of three other strong contenders R K Dutta, Maharashtra DGP Satish Mathur and ITBP director general Krishna Chaudhary .

Verma's appointment will also leave Delhi police headless and the government will have to soon choose the next commissioner. Two senior IPS officers Dharmendra Kumar and Deepak Misra -are in line for the post.

2019, interim: M Nageswara Rao and SC contempt

Rejects Apology, Fines Him, Legal Adviser ₹1L Each

In yet another blow to the CBI, the Supreme Court convicted its former interim chief, M Nageswara Rao, as well as additional legal adviser Bhasuran S for contempt of court and sentenced them to confinement till the rising of the court, besides imposing a fine of Rs 1 lakh each.

The two had attracted the court’s ire for shifting joint director A K Sharma out of the CBI in disregard of the court order that the latter be retained as in-charge of probe into the Muzaffarpur shelter home rape cases.

Both Rao and Bhasuran were told to “sit in a corner and remain inside till the rising of the court”. They were made to sit at the left-hand side visitors’ gallery of the courtroom and were not allowed to go out even during lunch time from 1-2pm, when the bench had risen.

This is the first time a top officer of the CBI and a legal adviser have been punished for contempt of court. A bench of Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice L Nageswara Rao showed no leniency to the contemnors after going through the file noting on relieving Sharma from the CBI in an unusually expeditious manner on January 18 after the Centre decided to promote him as additional director general of the CRPF.

Apology, though stated to be unconditional, isn’t so: SC

In our considered view, the present is a case where contempt has been committed, both by Nageshwar Rao, then in-charge CBI director (now additional director, CBI) and Bhasuran S, additional legal adviser and incharge director of prosecution, CBI. The apology tendered, though stated to be unconditional, is not so. There is a submission/contention that the actions were not wilful, with which contention, we are in total disagreement,” the bench said.

Octogenarian AG K K Venugopal tried hard to get the court to relent, arguing that it was not a case of wilful default and also that the two officers had apologised unconditionally. “To err is human and to forgive is divine,” said the AG.

But the plea failed to mollify the SC’s anger.

The bench said, “For commission of contempt of court, we sentence them till the rising of the court and impose a fine of Rs 1 lakh each on Rao and Bhasuran, to be deposited within a week.”

At around 3.30pm, the AG, accompanied by the two contemnors, made another attempt for leniency by pleading that they were tendering an unconditional apology and be allowed to go. But the CJI-led bench said: “We have sentenced you to sit inside the court till the rising of the bench. Hope you do not want it to be extended till tomorrow.”

Rao and Bhasuran finally walked out of the courtroom at 4.30pm.

A K Sharma, considered close to Verma — the former director who was removed because of the charges facing him — lost the key position of joint director (policy) after Nageshwar Rao took over as the interim director in October.

He got back the coveted perch in January when the SC restored Verma, with the latter reversing all transfers and postings effected under Rao. Sharma could continue at the key station only for two days as a PM-led panel removed Verma and Rao returned as interim director.

The bench found that Rao was aware of the two SC orders in a petition relating to the Muzaffarpur rape cases, directing that Sharma must not be shifted out as he was in charge of the probe. In fact, the examination of documents showed that Rao had raised the issue of the SC bar on shifting Sharma out with Bhasuran and was advised that Sharma, who has been promoted as ADG of CRPF, could be shifted out and the court only had to be informed about it.

Rishi Kumar Shukla, 2019-

From: Neeraj Chauhan, PM, CJI outvote Kharge, pick ex-MP DGP as new CBI chief, February 3, 2019: The Times of India

The Prime Minister Narendra Modi-led selection panel appointed 1983-batch Madhya Pradesh cadre IPS officer Rishi Kumar Shukla as the new CBI director on Saturday by a 2-1 vote, with the Congress’ leader in Lok Sabha giving a note of dissent against the choice of the PM and Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi.

In his note of dissent, Mallikarjun Kharge said the government ignored the need for experience in anti-corruption investigation while picking Shukla, who was last week removed as the MP police chief by the newly-elected Congress government, for the post. In his note, Kharge proposed an alternative panel of Javeed Ahmed, R R Bhatnagar and Sudeep Lakhtakia as probables, claiming that Shukla has “nil” experience in anti-graft probes.

Junior personnel minister Jitendra Singh, however, rebutted the charge saying that the selection was done on the basis of the criteria endorsed by CJI Gogoi. The criteria included “experience of 100 months in investigation”, he added. Shukla has 117 months of experience.

“He (Kharge) wanted to include some officers of his preference in the shortlist of candidates. Whatever is being said by him is totally unfounded and not based on facts. For the selection of the CBI director, very objective criteria was followed,” Singh added. Government sources said the selection panel finalised a list of eight names in its second meeting on Friday and Shukla was among the top choices considering his “seniority”.

Directors investigated by CBI

A P Singh

Neeraj Chauhan, CBI books one of its ex-chiefs for corruption, Feb 21 2017: The Times of India

AP Singh Faces Probe In Moin Qureshi Case

The Central Bureau of Investigation has booked its former director, A P Singh, as an “accused“ under the Prevention of Corruption Act to probe his association with meat exporter Moin Qureshi, allegedly a middleman for senior officers and politicians.

The agency conducted raids at Singh's residence in Defence Colony , the premises of Moin Qureshi and another key accused and Hyderabad-based businessman Pradeep Koneru and others in Delhi, Ghaziabad, Chennai and Hyderabad. It is the first time that CBI has on its own initiated a probe against its ex-director in a corruption case.CBI's probe against another former chief of the agency, Ranjit Sinha, who succeeded Singh, was at the instance of the Supreme Court. Among other things, CBI has based its case against Singh on BlackBerry messages exchanged. Many messages mentioned in the FIR refer to amounts Qureshi allegedly deposited in the accounts of Singh's daughter, Ragini Behrar, who was in London.The alleged exchanges have Qureshi regretting a dip in transfers during what he called a “lean season in meat business“ and Singh's daughter thanking him for making her “so rich“.

In another message allegedly sent by BBM to Qureshi, who was identified by the Enforcement Directorate as a middleman for certain public officials, Singh purportedly asked him to get a packet delivered at 37, Slaidburn St, presumably an address in London. Another BBM message cited in the FIR has Qureshi seeking help for a “family friend“, a former chairman of a public sector bank who was being investigated in agraft case. Singh, in his reply to Qureshi on BBM, said that the chargesheet had already been filed in the case and Qureshi's family friend could get help only from the court.

The exchanges between the two continued after Singh had left CBI and one of the alleged exchanges on BBM show Qureshi trying to help an aviation logistics firm for which he had planned to approach two senior politicians. Singh responded by suggesting that Qureshi approach someone else, a person whose surname matched that of a powerful minister.

A 1974 batch IPS officer, Singh headed the probe agency between November 30, 2010 and November 30, 2012, when the Congress was in power.His tenure saw the arrest of former telecom minister A Raja and several corporate bigwigs in connection with the 2G spectrum allocation scam, former Indian Olympics Association chief Suresh Kalmadi in the 2010 Commonwealth Games scam and the Aarushi-Hemraj murder probe. He was appointed a member of the Union Public Service Commission by the UPA government. However, a tax evasion probe by the income tax department against Qureshi brought out their close links. The probe saw the Modi government putting his appointment in the deep freezer, leading Singh to decline the appointment.

In a report filed in SC in October 2014, on the basis of the I-T department probe, attorney general Mukul Rohatgi had said, “The report reveals an astonishing state of affairs (that is) wholly unbecoming and revealing the shocking conduct of a former CBI director, now a member of the UPSC. He was in regular touch with Qureshi and there were BBM exchanges between them on a daily basis and that too in code language.Many of the messages clearly revealed plans to save the accused in many cases.“

In 2016, Qureshi had managed to leave the country without informing any authority despite having a lookout circular against him. He, however, came back in a few days.

Directors’ terms

Why CBI chief’s tenure is unique

Bharti Jain, October 25, 2018: The Times of India

The sanctity of CBI director’s fixed two-year tenure is unique vis-a-vis other secretary-level posts with its mandate from the Supreme Court. The fixed tenure enjoyed by the cabinet secretary and secretaries of home, defence and foreign as well as directors of Intelligence Bureau and RAW, on the other hand, is governed by executive rules that can be altered by a minister’s order.

Perhaps that is why in the past, governments led by both Congress and BJP have shunted out senior bureaucrats midway through their “fixed” two-year terms.

A senior IAS officer said while the fixed tenure rule was provided for certain posts in All-India Services Rules, they were only executive rules and could be changed with mere approval of the minister.

The cabinet secretary’s post was the first to get a fixed two-year term. The UPA government later included secretaries of home and defence secretary. A former secretary (personnel) said while the fixed two-year term was specified for certain posts, it was silent on early curtailment. “But one can always send a bureaucrat on leave, prevail upon him to resign or opt for early retirement,” said another officer.

General consent for investigating cases in a state

In 2018 and 2019, some states ruled by opposition parties, notably Andhra Pradesh, Bengal and Chhattisgarh, withdrew the ‘general consent’ that had been given to the CBI for investigating cases in their states.

The legal position

CBI can still move court if it wants to probe case in Maha, October 22, 2020: The Times of India

Mumbai/New Delhi:

The Uddhav Thackeray government’s decision to withdraw ‘general consent’ to the CBI means the central agency cannot investigate a case in Maharashtra on its own but will not turn the state into a forbidden territory.

Under the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act which governs the CBI, it is mandatory for the probe agency to secure the consent of state governments for investigating central government employees stationed within their geographical boundaries. State governments readily give the “consent” as otherwise the agency would be required to come rushing to them each time it wants to investigate an employee belonging to the I-T department, customs, railways or a CPSU. ‘General consent’ or ‘prior permission’ spares the CBI and the state governments the hassle of obtaining and giving consent for each case. For cases against state government employees or violent and serious crimes within a state, the CBI, in any case, cannot move in without specific consent of the state government concerned or directives by HCs and Supreme Court. Specific consent, by very definition, is limited to a particular case.

Now that the Maharashtra coalition has chosen to withdraw the ‘general consent’, the CBI will be required to seek consent each time it wants to take action against a Central government employee in Maharashtra — a situation they already face in West Bengal, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh.

But the order does not turn Maharashtra into a “nogo” territory for CBI which can continue to investigate cases registered before the state government withdrew consent. Withdrawal of consent, if any, by a state can be effected prospectively and not retrospectively. CBI can also probe people based in Maharashtra who are found involved in cases registered in other states.

While it may not be practically possible for the agency to carry out raids and arrests if the state government and police refuse to cooperate, it can overcome the problem by approaching courts. There have been several examples of courts allowing such pleas by the CBI.

Also, while CBI cannot register fresh cases in Maharashtra, it can conduct investigations in the state by getting a case registered in another state where it does not suffer from similar disability. Again, there have been instances of courts ruling in the agency’s favour in such situations.

Still, the order puts CBI in an unviable situation, given the number of central government employees in Maharashtra and Mumbai being the financial capital. The state is home to several public sector undertakings and a base of legions of I-T and customs personnel — something which explains why the agency had to split the state into four zones.

General consent: a backgrounder

Andhra, Bengal have withdrawn general consent for CBI investigation. Why does CBI need consent, how many states have granted or denied it, how far will the denial restrict CBI in the two states?

the Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal governments withdrew “general consent” to the CBI for investigating cases in their respective states. The state governments said they had lost faith in the CBI in the backdrop of its internal turmoil marked by the open war among the agency’s top officers. They have also alleged that the Centre is using the CBI to unfairly target Opposition parties.

What is general consent?

Unlike the National Investigation Agency (NIA), which is governed by its own NIA Act and has jurisdiction across the country, the CBI is governed by the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act that makes consent of a state government mandatory for conducting investigation in that state.

There are two kinds of consent: case-specific and general. Given that the CBI has jurisdiction only over central government departments and employees, it can investigate a case involving state government employees or a violent crime in a given state only after that state government gives its consent.

“General consent” is normally given to help the CBI seamlessly conduct its investigation into cases of corruption against central government employees in the concerned state. Almost all states have given such consent. Otherwise, the CBI would require consent in every case. For example, if it wanted to investigate a bribery charge against a Western Railway clerk in Mumbai, it would have to apply for consent with the Maharashtra government before registering a case against him.

What does withdrawal mean?

It means the CBI will not be able to register any fresh case involving a central government official or a private person stationed in these two states without getting case-specific consent. “Withdrawal of consent simply means that CBI officers will lose all powers of a police officer as soon as they enter the state unless the state government has allowed them,” said a former CBI officer who has handled policy.

Under what provision has general consent been withdrawn?

GO (government order) number 176 issued by the Andhra Pradesh Home Department by Principal Secretary A R Anuradha on November 8 states: “In exercise of power conferred by Section 6 of the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act, 1946 (Central Act No 25 of 1946), the government hereby withdraws the general consent accorded in GO No 109 Home (SC.A) Department dated August 3, 2018 to all members of the Delhi Special Police Establishment to exercise the powers and jurisdiction under the said Act in the State of Andhra Pradesh.’’

Section 6 of the Act says, “Nothing contained in Section 5 (which deals with jurisdiction of CBI) shall be deemed to enable any member of the Delhi Special Police Establishment to exercise powers and jurisdiction in any area in a State, not being a Union Territory or Railway, area, without the consent of the Government of that State.”

Does that mean that the CBI can no longer probe any case in the two states?

No. The CBI would still have the power to investigate old cases registered when general consent existed. Also, cases registered anywhere else in the country, but involving people stationed in Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal, would allow CBI’s jurisdiction to extend to these states.

There is ambiguity on whether the agency can carry out a search in either of the two states in connection with an old case without the consent of the state government. However, there are legal remedies to that as well. The CBI can always get a search warrant from a local court in the state and conduct searches. In case the search requires a surprise element, there is CrPC Section 166, which allows a police officer of one jurisdiction to ask an officer of another to carry out searches on his behalf. And if the first officer feels that the searches by the latter may lead to loss of evidence, the section allows the first officer to conduct searches himself after giving a notice to the latter.

What happens in fresh cases?

Withdrawal of consent will only bar the CBI from registering a case within the jurisdiction of Andhra and Bengal. The CBI could still file cases in Delhi and continue to probe people inside the two states.

An October 11, 2018, order of the Delhi High Court makes it clear that the agency can probe anyone in a state that has withdrawn “general consent” if the case is not registered in that state. The order was given with regard to a case of corruption in Chhattisgarh, which also gives consent on a case-to-case basis. The court ordered that the CBI could probe the case without prior consent of the Chhattisgarh government since it was registered in Delhi.

Thus, if a state government believes that the ruling party’s ministers or members could be targeted by CBI on orders of the Centre, and that withdrawal of general consent would protect them, it would be a wrong assumption, experts say. A CBI officer said: “CBI could still register cases in Delhi which would require some part of the offence being connected with Delhi and still arrest and prosecute ministers or MPs. The only people it will protect is small central government employees.”

Is it the first time a state government has withdrawn consent?

No. Over the years, several states have done so, including Sikkim, Nagaland, Chhattisgarh and Karnataka — which stands out as an example. In 1998, the Janata Dal-led government of J H Patel had withdrawn general consent. In 1999, the S M Krishna-led Congress government took over and did not revoke Patel’s order. The then state Home Minister was Mallikarjun Kharge, current Leader of the Congress in Lok Sabha. “General consent wasn’t renewed for eight long years. The CBI had to virtually close down its office,” said an officer who was in the CBI then. He added that the agency had to seek permission of the state government for every case and every search it conducted on central government employees.

A

Deeptiman Tiwary, November 12, 2021: The Indian Express

The Supreme Court expressed concern over a submission by the CBI that since 2018, around 150 requests for sanction to investigate have been pending with eight state governments that have withdrawn general consent to the agency.

“It is not a desirable position,” a Bench led by Justice S K Kaul observed, and referred the matter to Chief Justice of India N V Ramana.

The CBI had filed the affidavit after the court inquired last month about the bottlenecks it faced, and the steps it had taken to strengthen prosecutions.

What is general consent?

The National Investigation Agency (NIA), which is governed by The NIA Act, 2008, has jurisdiction across the country. But the CBI is governed by The Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act, 1946, and must mandatorily obtain the consent of the state government concerned before beginning to investigate a crime in a state.

The consent of the state government can be either case-specific or general.

A “general consent” is normally given by states to help the CBI in seamless investigation of cases of corruption against central government employees in their states. Almost all states have traditionally given such consent, in the absence of which the CBI would have to apply to the state government in every case, and before taking even small actions.

Section 6 of The DSPE Act (“Consent of State Government to exercise of powers and jurisdiction”) says: “Nothing contained in section 5 (“Extension of powers and jurisdiction of special police establishment to other areas”) shall be deemed to enable any member of the Delhi Special Police Establishment to exercise powers and jurisdiction in any area in a State, not being a Union territory or railway area, without the consent of the Government of that State.”

Which states have withdrawn general consent, and why?

Eight states have currently withdrawn consent to the CBI: Maharashtra, Punjab, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, and Mizoram. All except Mizoram are ruled by the opposition.

Mizoram in fact, was the first state to withdraw consent in 2015. The state was ruled by the Congress at the time, and Lal Thanhawla was chief minister. In 2018, the Mizo National Front (MNF) under Zoramthanga came to power; however, even though the MNF is an NDA ally, consent to the CBI was not restored.

In November 2018, the West Bengal government led by Mamata Banerjee withdrew the general consent that had been accorded to the CBI by the previous Left Front government back in 1989. West Bengal announced its decision within hours of Andhra Pradesh, then ruled by N Chandrababu Naidu’s TDP, taking a similar decision.

“What Chandrababu Naidu has done is absolutely right. The BJP is using the CBI and other agencies to pursue its own political interests and vendetta,” Banerjee said.

After Naidu’s government was replaced by that of Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy in 2019, however, Andhra Pradesh restored consent.

The Congress government of Bhupesh Baghel in Chhattisgarh withdrew consent in January 2019. Punjab, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Kerala, and Jharkhand followed in 2020. At the time of withdrawing consent, all states alleged that the central government was using the CBI to unfairly target the opposition.

What does the withdrawal of general consent mean?

It means the CBI will not be able to register any fresh case involving officials of the central government or a private person in the state without the consent of the state government.

“CBI officers will lose all powers of a police officer as soon as they enter the state unless the state government has allowed them,” a former CBI officer who has handled policy during his time in the agency, said.

Calcutta High Court recently ruled in a case of illegal coal mining and cattle smuggling being investigated by the CBI, that the central agency cannot be stopped from probing an employee of the central government in another state. The order has been challenged in the Supreme Court.

In Vinay Mishra vs the CBI, Calcutta HC ruled in July this year that corruption cases must be treated equally across the country, and a central government employee could not be “distinguished” just because his office was located in a state that had withdrawn general consent.

The HC also said that withdrawal of consent would apply in cases where only employees of the state government were involved.

The petition had challenged the validity of FIRs registered by the CBI’s Kolkata branch after the withdrawal of consent.

So where does the CBI currently stand in these eight states?

The agency can use the Calcutta HC order to its advantage until it is — if it is — struck down by the Supreme Court. Even otherwise, the withdrawal of consent did not make the CBI defunct in a state — it retained the power to investigate cases that had been registered before consent was withdrawn. Also, a case registered anywhere else in the country, which involved individuals stationed in these states, allowed the CBI’s jurisdiction to extend to these states.

There is ambiguity on whether the CBI can carry out a search in connection with an old case without the consent of the state. But the agency has the option to get a warrant from a local court in the state and conduct the search.

In case the search requires an element of surprise, Section 166 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) can be used, which allows a police officer of one jurisdiction to ask an officer of another to carry out a search on their behalf.

And should the first officer feel that a search carried out by the latter may lead to loss of evidence, the section allows the first officer to conduct the search himself after giving notice to the latter.

Finally, consent does not apply in cases where someone has been caught red-handed taking a bribe.

But what about fresh cases?

Again, the CBI could use the Calcutta HC order to register a fresh case in any state. Alternatively, it could file a case in Delhi and continue to investigate people inside these states.

In an order passed on October 11, 2018, Delhi High Court ruled that the agency could probe anyone in a state that has withdrawn general consent, if the case was not registered in that state. The order came on a case of corruption in Chhattisgarh — the court said that since the case was registered in Delhi, the CBI did not require prior consent of the Chhattisgarh government.

In sum, avenues remain available to the CBI to proceed even without consent. “The CBI could register cases in Delhi if some part of the offence is connected with Delhi, and still arrest and prosecute individuals in these states,” a CBI officer said.

Have states started denying consent only after the present government came to power in Delhi?

No. States, including Sikkim, Nagaland, Chhattisgarh and Karnataka, have done this throughout the history of the agency. In 1998, the Janata Dal government of Chief Minister J H Patel withdrew general consent to the CBI in Karnataka. The Congress government of S M Krishna, which took over in 1999, did not revoke the previous government’s order. The home minister of Karnataka then was Mallikarjun Kharge, the current Leader of Opposition in Rajya Sabha.

“Consent wasn’t renewed for eight long years. The CBI had to virtually close down its office (in Karnataka),” said an officer who was with the agency at the time. The CBI had to seek the permission of the state government for every case and every search it conducted on central government employees, the officer said.

Political accusations aside, to what extent is the CBI “its master’s voice”?

After the 2018 amendments to the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, the Centre has come to exercise power over the CBI not just administratively, but also legally.

In 2018, the government pushed through Parliament amendments to Section 17A of the Act, making it mandatory for the CBI to seek the Centre’s permission before registering a case of corruption against any government servant.

Earlier, the Centre had mandated that such permission was required only for officials of the level of joint secretary and higher. The amendments were brought after the Supreme Court struck down the government’s directive.

CBI officers say the 2018 amendment virtually means the agency can investigate only the officers that the government of the day wants investigated. In fact, corruption cases registered by the CBI dropped by over 40 per cent between 2017 and 2019.

Jurisdiction

State government’s consent mandatory in its jurisdictions

November 19, 2020: The Times of India

The Supreme Court has said that the provision making the state government’s consent mandatory for a CBI probe in their respective jurisdictions is in tune with the principle of federalism and the Centre cannot extend the jurisdiction of the agency to a state without its consent.

Referring to Section 5 and 6 of the Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act that regulates CBI’s functioning, a bench of Justices A M Khanwilkar and B R Gavai said, “It could thus be seen, that though Section 5 enables the Central Government to extend the powers and jurisdiction of members of the DSPE beyond the Union Territories to a state, the same is not permissible unless, a state grants its consent for such an extension within the area of state concerned under Section 6 of the DSPE Act.”

8 states have withdrawn nod for CBI probe in fresh cases

The verdict comes in the wake of eight non-BJP states having so far withdrawn general consent for CBI to probe fresh cases, Punjab being the last one to do so. The others are Jharkhand, Kerala, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Mizoram. Andhra Pradesh was among the first to withdraw consent, but Jagan Reddy restored it soon after coming to power.

“Obviously, the provisions are in tune with the federal character of the Constitution, which has been held to be one of the basic structures of the Constitution,” the court said. The bench passed the order on an appeal filed by accused challenging validity of the CBI probe against them in a corruption case on the ground that prior consent was not taken from state government. Two of the accused are state government employees and the rest are private parties, including one company.

Rejecting their appeal, the court said the state of UP had accorded a general consent for extension of powers and jurisdiction of the members of Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) in 1989 in the whole of state under the Prevention of Corruption Act, “The same is however with a rider, that no such investigation shall be taken up in cases relating to public servants, under the control of the state government, except with prior permission of the state government. As such, insofar as the private individuals are concerned, there is no embargo with regard to registration of FIR against them,” the bench said.

The bench ruled against government employees also saying that “there are no pleadings by public servants with regard to the prejudice caused to them on account of non-obtaining of prior consent under Section 6 of the DSPE Act qua them specifically in addition to the general consent in force, nor with regard to miscarriage of justice”.

The bench passed the order on an appeal filed by accused challenging validity of the CBI probe against them in a corruption case on the ground that prior consent was not taken from state government

Pressures on CBI

…especially when probing politicians; 1948- 2018

Connection counts in India, especially to keep the police, or the CBI, at bay. Since independence, ruling political parties have maintained a firm grip over investigating agencies and the prosecution and decide when a criminal case should be filed against an opponent and a pending case against a friend be closed. The police, the CBI or the prosecution seldom had the independence to chart the course of politically sensitive cases.

Immediately after independence, then India’s high commissioner to the UK V K Krishna Menon ignored protocol and signed a Rs 80 lakh contract with a foreign firm for supply of 200 jeeps to the Army. Contract money was paid upfront but only 155 jeeps reached India. A probe began but was abruptly closed by then PM Jawaharlal Nehru, who forced home minister G B Pant to shut the files. Menon’s proximity to the then PM came handy. Since then, the ruling class has never let go an opportunity to dictate the course of investigation in a case to the CBI. Often, pliant CBI directors complied with political diktats, unconcerned with the merit of cases.

In the last 22 years, constitutional courts have unfolded the blatant interference in CBI probes into politically sensitive cases. First was the JMM MPs bribery case, where the Congress government led by P V Narasimha Rao attempted to misdirect the CBI probe right from the time of registration of FIR. A tenacious Delhi HC bench of Justices Y K Sabharwal and D K Jain had scooped out the details.

Rashtriya Mukti Morcha had lodged a complaint with the CBI on February 1, 1996, alleging that the Congress government won the vote of confidence in July 1993 by a wafer thin majority after buying votes of MPs from JMM and JD-A. It had produced account details of one JMM MP, who had naively deposited the bribe money in the bank. Despite clear evidence, the CBI headed by K Vijaya Rama Rao diluted the FIR so as to prevent embarrassment to PM Rao. The director was caught redhanded by the HC bench, admonished and the CBI was ordered to register a proper FIR.

Ironically, the Rao government had set up a commission headed by N N Vohra in July 1993 to unearth the unholy politician-bureaucrat-police-mafia nexus. The nexus continues to prosper despite the Vohra committee identifying the malaise and suggesting remedial measures, which never got seriously implemented.

Then came the coalition era at the Centre and the Bofors scam. For decades, the case was on and off the CBI’s burner depending on the political strength and manoeuvring of Congress, which was erecting and dismantling coalition governments at its whim. The gun proved its mettle but the CBI lost credibility. One of the main suspects Ottavio Quattrocchi escaped the law. The Congress government allowed de-freezing of his London account. It also refused permission to appeal in the Argentina SC for his extradition. As the gun silenced its opponents in the Kargil war, lapse of time numbed the prosecution. The Delhi HC quashed the case. The CBI took more than a decade to file an appeal in the SC.

In 2003, the SC ordered the CBI to register an FIR against BSP chief Mayawati in the Taj Heritage Corridor scam. The probe meandered on and off track, depending on BSP’s usefulness to the central government. In 2006, the then AG agreed with the CBI that the case needed closure. The SC sought the opinion of the CVC, which said there was enough evidence to prosecute her. The CBI finally decided to file a chargesheet but UP governor T V Rajeswar declined sanction based on a 262-page opinion given by a law officer of UPA.

When Mayawati was in the good books of Congress-led UPA, Mulayam Singh Yadav was not. On a PIL, the SC had ordered a probe by CBI into Malayam and his family’s disproportionate assets. The agency proceeded with zeal and came out with meticulous details of his and family members’ income to tell the SC that there was enough evidence to prosecute Mulayam and his family members.

Political equations change dramatically. It was Mulayam and his party’s sizeable number of MPs which bailed out the UPA government in Parliament over the India-US nuclear deal, which caused Left parties to leave the coalition. The seasoned Mulayam demanded his pound of flesh. An indebted Manmohan Singh government readily obliged and the CBI accomplished a seemingly difficult task of re-calculating the assets’ value and sheepishly inform SC that the Yadavs’ had no disproportionate assets.

The CBI has competent investigating officers, who have time and again displayed their ability to crack difficult cases which did not involve politicians. The Ghaziabad PF scam, in which the scanner was on some constitutional court judges, was probed fearlessly. But the CBI top brass showed rubbery backbones and bent to the wishes of the ruling dispensation whenever it took up investigations into politically sensitive cases.

The list of beneficiaries and sufferers are many and include Lalu Prasad, Rabri Devi, Shibu Soren and Ajit Jogi. The heavy feet of the agency were best exhibited in the criminal case relating to demolition of Babri Masjid, which started in December 1992 and is still dragging on.

The CBI’s instinctive reflex action to bend before political power was palpable in the SC monitored coal scam probe. The agency director had rushed to get its probe status report, to be filed in the SC, vetted by UPA law minister Ashwani Kumar before putting it before the SC bench. This was unacceptable to the SC as it was getting the feel of the scam reaching the doors of PM Manmohan Singh. This action of the CBI, coupled with its past approach of being obedient to the master, led the SC to christen it ‘caged parrot’, a tag that the agency is finding difficult to shed.

The systematic dismantling, destruction and devaluing of CBI has been going on with impunity for decades. What we will see in future could be worse, unless someone with integrity and firm backbone assumes leadership of CBI. The sooner it is, the better it will be for the country.

International ambit

2016

CBI director Anil Sinha said in 2016 that 392 of its criminal investigations, which have international angles to them, are pending in 66 countries.

The central anti-corruption agency has many investigations where it needs information from several countries including 2G scam, AgustaWestland scam, the defence scandal related to Embraer and India deal. CBI is India’s nodal agency for the transnational organised crime, Interpol, anti-corruption and bank frauds. (The Times of India)

Jurisdiction

Limits of CBI jurisdiction

Can States bar the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) from functioning in their territory?

Yes. The CBI is a national agency with police powers. Its primary jurisdiction is confined to Delhi and Union Territories. As policing (detecting crime and maintaining law and order) is a State subject, the law allows the agency to function outside only with the consent of the States. Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal have withdrawn their general consent to the CBI to operate within their territories.

Has it happened before? And why?

There are several instances of State governments withdrawing their consent. There was even an instance in Sikkim, when the State withdrew its consent after the CBI registered a case against former Chief Minister Nar Bahadur Bhandari, and before it could file a charge sheet. The most common reason for withdrawal of consent is a strain in Centre-State relations, and the oft-repeated allegation that the agency is being misused against Opposition parties. The decision by Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal has come amid concerns being voiced by Opposition parties that Central agencies such as the CBI, Enforcement Directorate and Income Tax Department are being used against them.

Under what law is it done?

The CBI draws its power from the Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act. The Home Ministry, through a resolution, set up the agency in April 1963. Under Section 5 of the Act, the Central government can extend its powers and jurisdiction to the States, for investigation of specified offences. However, this power is restricted by Section 6, which says its powers and jurisdiction cannot be extended to any State without the consent of the government of that State.

What is the impact of States taking back their consent?

The withdrawal of general consent restricts the CBI from instituting new cases in the State concerned. However, as decided by the Supreme Court in Kazi Lhendup Dorji (1994), the withdrawal of consent applies prospectively and therefore, existing cases will be allowed to reach their logical conclusion. The CBI can also seek or get specific consent in individual cases from the State government.

How has the consent issue played out?

In most cases, States have given consent for a CBI probe against only Central government employees. The agency can also investigate a Member of Parliament. Apart from Mizoram, West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh, the agency has consent in one form or the other for carrying out investigations across the country.

What happens to cases in which there is a demand for a CBI probe?

The Supreme Court has made it clear that when it or a High Court directs that a particular investigation be handed over to the CBI, there is no need for any consent under the DSPE Act. A landmark judgment in this regard was the 2010 Supreme Court decision by which the killing of 11 Trinamool Congress workers in West Bengal in 2001 was handed over to the CBI.

2018: AP, Bengal withdraw “general consent”

The fight between oppositioncontrolled states and the BJPled Centre intensified dramatically on Friday with Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal forbidding CBI and other central agencies from operating within their boundaries.

In a marked escalation, governments led by Chandrababu Naidu and Mamata Banerjee, both of whom are busy trying to erect an anti-BJP front, withdrew the “general consent” extended to the CBI.

Naidu justified the move by saying the CBI had been reduced to a tool for blackmail by the Centre, an accusation which was soon endorsed by Banerjee as she followed suit.

“The CBI has lost its credibility,” the Trinamool boss said. West Bengal, incidentally, was the first state to open its doors to the CBI.

BJP alleged that a “coalition of corrupt parties” was taking shape in the country and the party would raise this issue at all political platforms. “Recent happenings in the CBI have been cited as a lame excuse and a ruse to brazenly save the corrupt and extend political patronage to people and organisations involved in acts of corruption and criminality,” BJP’s G V L Narasimha Rao said.

In fact, Andhra Pradesh’s move was not limited to the CBI. It withdrew consent also with regard to implementation of 63 central Acts and 188 different sections of the IPC — a drastic move which many in the government believe might hinder probe and action by central agencies that deal with offences such as hijacking, smuggling of antiquities, and those covered under central laws dealing with arms, atomic energy, benami transactions, customs, explosives, passports and money-laundering.

Personnel issues

Dir Verma vs, SplDir Asthana

From: Neeraj Chauhan, No. 1 vs No. 2 war in CBI escalates, DSP in Asthana’s team arrested, October 23, 2018: The Times of India

From: October 24, 2018: The Hindu

From: October 24, 2018: The Hindu

From: October 25, 2018: The Times of India

From: Five charges that hurt ousted CBI chief Alok Verma, January 11, 2019: The Times of India

Govt May Ask NSA Doval To Examine Facts

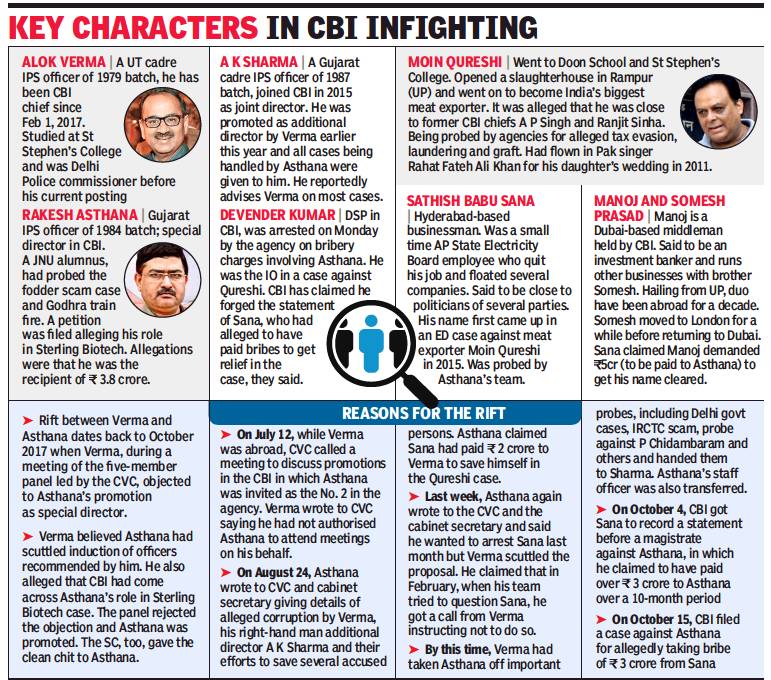

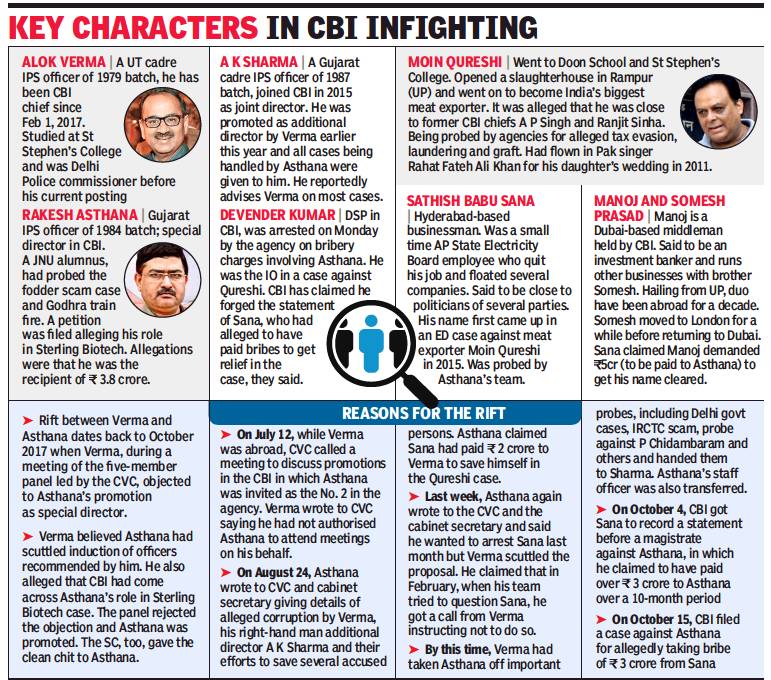

The internal war within India’s premier investigative agency, the CBI, escalated with the arrest of DSP Devender Kumar, who, along with special director Rakesh Asthana, has been accused of taking Rs 3 crore in bribes from businessman Sathish Babu Sana.

The action against Kumar, whose office was searched by the agency, was seen as a declaration of intent by CBI director Alok Verma to take the FIR against his rival Asthana to its logical culmination and

as a pointer to the sordid lengths to which the factional blood-letting might go.

The agency has named Asthana as accused number one in its FIR registered on October 15 on the basis of a complaint from Sana, promoter of Playboy Club in Hyderabad. Another accused in the case, Dubai-based investment banker Manoj Prasad, has already been arrested.

The repercussions of the strife will travel beyond what happens to the combatants; it has opened a bloody sore at the heart of the government. Besides threatening to chip at its claim of strong and decisive governance, it raises questions about the fate of sensitive cases being handled by Asthana, like the ones against Vijay Mallya and the AgustaWestland scam. The matter was already causing concern to the government and there were indications that NSA Ajit Doval might be asked to look at the facts.

Asthana was said to be exploring legal options in the face of what sources close to him ter med a “vicious effort” by Verma and other factional rivals, as well as a few working for other agencies, to thwart him from becoming the CBI chief by “framing” him in a “false corruption case”. The CBI was yet to show recovery of the bribe amount that DSP Kumar and Asthana allegedly extorted from Sana.

As reported earlier, Sana was being probed by an SIT led by Asthana for a suspicious transaction of Rs 50 lakh with Moin Qureshi, a meat exporter accused in a money-laundering case. During its investigation, the SIT chanced upon evidence of alleged payment of bribe of Rs 2 crore to the CBI chief by Sana with the help of a Rajya Sabha member belonging to a regional party. Asthana communicated this to the CVC on August 24. On September 26, Sana allegedly admitted, in a statement before Kumar, to paying a Rs 2 crore bribe to the CBI chief.

But in a dramatic turn of events just 19 days later, the CBI registered an FIR against Asthana for allegedly taking a bribe of Rs 3 crore from Sana, whom he wanted to arrest.

CBI spokesperson Abhishek Dayal said Sana’s statement against Verma was fabricated by Kumar as an “afterthought” to substantiate the charge that Asthana levelled against Verma in his complaint to the CVC.

BJP concerned about implications

BJP expressed concern on Monday about the implications for the credibility of the CBI and said the government would take action to ensure it was not eroded. “We would like people’s faith in the institution of the CBI to continue,” BJP spokesperson Meenakshi Lekhi said.

Rahul says CBI in terminal decline

Congress chief Rahul Gandhi blamed the CBI internal war on the Centre’s interference and targeted special director Rakesh Asthana. “The PM’s blue-eyed boy... has now been caught taking bribes. An institution in terminal decline that’s at war with itself,” he tweeted.

Verma-Asthana clashes festered for over a year

CBI spokesperson Abhishek Dayal stressed on Monday that Sathish Babu Sana. was not in Delhi on September 26, the day when he purportedly admitted to DSP Devender Kumar that he had paid a bribe to CBI chief Verma — an assertion which meant the CBI has given a clean chit to Verma.

Sources close to Asthana, however, claimed that there was strong evidence of the Rajya Sabha MP meeting Verma to organise help for Sana.

Some in the agency expressed surprise over Asthana being named in the FIR based on Sana’s statement when the latter was already being investigated for bribery, and when there was no evidence of any contact between him, in person or through phone or email, and Asthana.

Asked why the agency didn’t take permission from the government as per Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption Act, the CBI said the provision didn’t apply in this case. The CBI also refused to comment on Asthana’s allegations against additional director A K Sharma’s family members running shell companies, saying the CVC was looking into the case.

The clash between Verma and Asthana has festered for over a year now since Verma first opposed Asthana’s elevation as special director, which was turned down by the CVC, the government and the Supreme Court.

Over the last 6-7 months, important cases handled by Asthana have been taken away from him while the CBI’s special unit has been reportedly unleashed on Asthana and his subordinates. In one of the letters written to the cabinet secretary on August 24, Asthana had claimed that “there have been concerted attempts by Verma, Rajeshwar Singh (joint director of the Enforcement Directorate) and others to tarnish” his image.

Verma is also learned to have given adverse remarks in Asthana’s performance report. Asthana alleged that this was being done to “adversely affect my career prospects”.

Verma vs Asthana: How it all started

Alok Verma vs Rakesh Asthana: How it all started, October 24, 2018: The Times of India

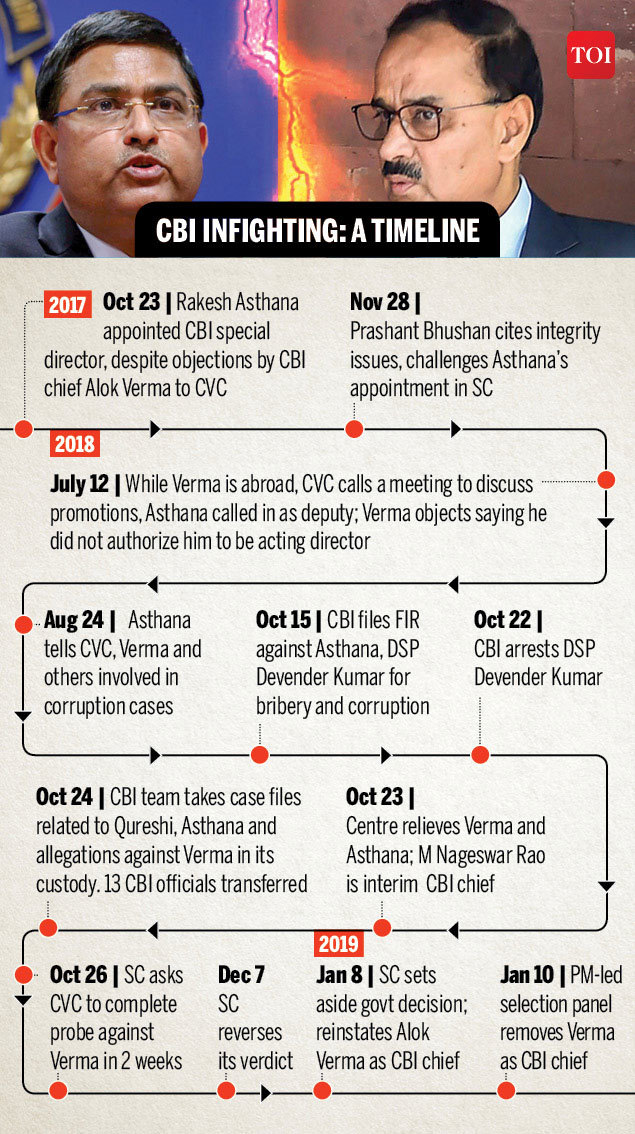

The government sent CBI director Alok Verma and special director Rakesh Asthana on leave and appointed M Nageshwar Rao as interim chief of the probe agency "with immediate effect".

The government's move to appoint Rao as interim CBI chief + comes a day after high-voltage drama involving director Alok Verma and special director Rakesh Asthana in the Delhi high court. But, the two have never been on good terms while serving in the agency, with each accusing the other of wrongdoing.

We take a look at the bitter feud in the agency. Here is how it all started:

- The rift between Verma and Asthana dates back to October 2017 when Verma, during a meeting of the five-member CVC, objected to Asthana's promotion as special director.

- Verma believed Asthana had scuttled induction of officers recommended by him. He also alleged that CBI had come across Asthana's role in the Sterling Biotech case. The panel rejected the objection and Asthana was promoted. The SC too, gave the clean chit to Asthana.

- On July 12, while Verma was abroad, CVC called a meeting to discuss promotions in the CBI in which Asthana was invited as the No. 2 in the agency. Verma wrote to CVC saying he has not authorised Asthana to attend meetings on his behalf.

- On August 24, Asthana wrote to CVC and cabinet secretary giving details of alleged corruption by Verma, his right-hand man additional director AK Sharma and their efforts to save several accused persons. Asthana claimed Sathish Babu Sana, Hyderabad-based businessman had paid Rs 2 crore to Verma to save himself in the Moin Qureshi case.

- Last week, Asthana again wrote to the CVC and the cabinet secretary and said he wanted to arrest Sana last month but Verma scuttled the proposal. He claimed that in February, when his team tried to question Sana, he got a call from Verma instructing not to do so.

- By this time, Verma had taken Asthana off important probes, including Delhi government cases, IRCTC scam, probe against P Chidambaram and others, and handed them to Sharma. Asthana's staff officer was also transferred.

- On October 4, the CBI got Sana to record a statement before a magistrate against Asthana, in which he claimed to have paid him Rs 3 crore over a 10-month period.

- On October 15, the CBI filed a case against Asthana for allegedly taking bribe of Rs 3 crore from Sana.

- On Tuesday, the Delhi high court directed the CBI to maintain status quo on the criminal proceedings initiated against the agency's special director Asthana and a trial court sent an arrested mid-level officer facing bribery charges to seven-day remand.

- Both Alok Verma and Rakesh Asthana sent on leave on October 24.

Asthana, Verma and the CBI slugfest

HIGHLIGHTS

Asthana, during his initial years in Gujarat, would often seek central deputations as he had little patience for how Congress leaders worked.

In 2002, when Modi was the Gujarat chief minister, Asthana was asked to head the Special Investigation Team (SIT) to probe the Sabarmati Express train tragedy.

CBI special director Rakesh Asthana, who was probing some of the biggest cases with the CBI - including the AgustaWestland scam, the INX media case, and the Vijay Mallya loan default - is the consummate insider.