Rock Art: Ladakh

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=Rock Art= | =Rock Art= | ||

| − | |||

==Ladakh: A potential for an Open Museum of Rock Art part 1== | ==Ladakh: A potential for an Open Museum of Rock Art part 1== | ||

| Line 46: | Line 41: | ||

Leh: As I have already mentioned in the previous issue (Part I) that Ladakh has a rich source of rock art in the form of Petroglyphs, enough to be an ‘open museum’. One of the richest sites of rock art is along the river Indus. For convenience, we may divide it as lower and upper Indus, Leh being the dividing point. It depicts the earliest expressions of humankind. It is associated with cultural values. They are irreplaceable records of the artists, his thought and reason for the art he has drawn. Here in Ladakh it could play a vital role in understanding the role played by these mountainous regions as a cultural crossroads from the prehistory to the present day. | Leh: As I have already mentioned in the previous issue (Part I) that Ladakh has a rich source of rock art in the form of Petroglyphs, enough to be an ‘open museum’. One of the richest sites of rock art is along the river Indus. For convenience, we may divide it as lower and upper Indus, Leh being the dividing point. It depicts the earliest expressions of humankind. It is associated with cultural values. They are irreplaceable records of the artists, his thought and reason for the art he has drawn. Here in Ladakh it could play a vital role in understanding the role played by these mountainous regions as a cultural crossroads from the prehistory to the present day. | ||

| + | |||

Phyang, Taroo, Umla, Basgo, Likir, Alchi, Nyurla all have some forms of prehistoric rock art. Some of the rocks in Basgo have been inundated due to the Alchi dam. One of the most important one with Kharoshti inscription near the Khaltse Bridge has been damaged. From Khaltse to Domkhar there are several sites worth noticing. Achinathang has some rock displaying human figures of rare representations. At Domkhar, particularly in the private compound of Thangjuk family lies one of the most beautiful forms of animal representations, a clear Central Asian art of more than two thousand years old. A scholar of rock art writes about this site as “This site is indeed a true gold mine for scientists and a possible key to better understand the ancient past of the lower Indus valley and thus potentially throw light on the ancient history of Ladakh, which up to present remains almost unknown”. There are also some Chinese inscriptions. The family has now made it a Rock Art Heritage Garden for visitors to enjoy. From Domkhar to Batalik there are another not less than dozen sites, each displaying some unique subject and forms. Near Bema, there is a large boulder with hundreds of figures, along with some Kharoshti inscriptions. At another site we have discovered pictograph (painting on the rock) which is rare to be found in Ladakh, it is yet to be studied in detail. | Phyang, Taroo, Umla, Basgo, Likir, Alchi, Nyurla all have some forms of prehistoric rock art. Some of the rocks in Basgo have been inundated due to the Alchi dam. One of the most important one with Kharoshti inscription near the Khaltse Bridge has been damaged. From Khaltse to Domkhar there are several sites worth noticing. Achinathang has some rock displaying human figures of rare representations. At Domkhar, particularly in the private compound of Thangjuk family lies one of the most beautiful forms of animal representations, a clear Central Asian art of more than two thousand years old. A scholar of rock art writes about this site as “This site is indeed a true gold mine for scientists and a possible key to better understand the ancient past of the lower Indus valley and thus potentially throw light on the ancient history of Ladakh, which up to present remains almost unknown”. There are also some Chinese inscriptions. The family has now made it a Rock Art Heritage Garden for visitors to enjoy. From Domkhar to Batalik there are another not less than dozen sites, each displaying some unique subject and forms. Near Bema, there is a large boulder with hundreds of figures, along with some Kharoshti inscriptions. At another site we have discovered pictograph (painting on the rock) which is rare to be found in Ladakh, it is yet to be studied in detail. | ||

| + | |||

Only some of these rock art has been studied, and few of them have been dated to around three thousand BC. This cultural heritage as we have seen has been neglected and at many places they have been destroyed and damaged. We still have time to protect these rocks or else they may disappear forever. There are about half a dozen of scholars (foreigners) who are studying, but I feel, we as a Ladakhi have the responsibility to protect them and be proud of these rare and historically significant art: equally as any other monuments. | Only some of these rock art has been studied, and few of them have been dated to around three thousand BC. This cultural heritage as we have seen has been neglected and at many places they have been destroyed and damaged. We still have time to protect these rocks or else they may disappear forever. There are about half a dozen of scholars (foreigners) who are studying, but I feel, we as a Ladakhi have the responsibility to protect them and be proud of these rare and historically significant art: equally as any other monuments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =As in 2024= | ||

| + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=18_08_2024_023_008_cap_TOI Malini Nair, August 18, 2024: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: One of her most rewarding finds has been what she calls the ‘Stone Temple’ of Skindisa in an uninhabited valley in Nubra.jpg|One of her most rewarding finds has been what she calls the ‘Stone Temple’ of Skindisa in an uninhabited valley in Nubra <br/> From: [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=18_08_2024_023_008_cap_TOI Malini Nair, August 18, 2024: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Ahtushi Deshpande is no stranger to the stunning trans Himalayan moonscape of Ladakh. As a solo trekker, she has traversed the landscape swept by broad brushstrokes of browns, beige, purple, white and turquoise several times. And revelled in its utter solitude and surprising finds. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

None of it, however, prepared the writer and photographer for the spectacle at Kawathang, 100 km from Leh where, standing out against the dark patina of worn rocks were etchings — beautiful, spare, mysterious and abstract. Especially intriguing were the delicate hand impressions, elongated fingers stretching upward. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

What were they trying to say across at least 5,000 years? Did they mark a tribe, an identity, or were they a sign of welcome? In an obsessive quest over 13 years and 18 journeys, Deshpande has documented more than 200 such sites across Ladakh. They can be found along the riverine stretch of the Indus which runs for 400 km through Ladakh as well as along ancient trails. Some are simply parked in the middle of nowhere on vast desertic stony flats. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

It is a formidable project — the terrain is inhospitable and mind-bogglingly vast and temperatures can drop to minus 40 degrees C in winters while summers stay bone dry. But the etchings and the stories they tell, says the 55-year-old, were irresistible. “They are big outdoor museums of rock art, all done in situ, on the toughest and most ungiving canvas there can be. It made me realise that we have forgotten how hardy and resilient we can be as a human race,” she says. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Some petroglyphs, as etched rocks are called, are known, some are hidden, and some simply a part of the mountain landscape that shepherds pass without a second look. There are hunting scenes on these rocks, rites of passage, scenes from community life, celebratory dancing and, of course, animals, most notably the ibex, a wild goat with dramatically arched horns. These densely engraved spare stick figures, which show great artistry, sophistication and imagination, have been captured in a stunningly illustrated book by Deshpande titled, ‘Speaking Stones: Rock Art of Ladakh’. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

There is an urgency to the work. Unlike cave art, which is still protected by its shelter dwelling, Ladakh’s petroglyphs stand open to the elements, and vulnerable to human interference. “Even in the 13 years I have travelled, I have seen rocks disappear, either into the waters or felled for road construction or painted over by graffiti or signage,” says Deshpande, stressing the need to preserve these ‘ancient canvases’. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

There are two journeys subsumed in Deshpande’s quest: one through the rarified air of Ladakh and the other through the fragility of life itself. She is a three-time breast cancer survivor, and the disease arrived four years after her Ladakh quest began. But she would rather not let what she calls “an errant cell” overcome the narrative on her book. “Cancer divides your life into two — the one before and the one after diagnosis. But Ladakh gave me the purpose to keep going instead of allowing the fear to overwhelm me. I am alive today and that is all that counts,” she says, and this is a philosophy that also defines her work with cancer support groups. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The earliest explorations of the petroglyphs began in 1905 with archaeologist August Hermann Francke but it was not until the 1980s, when access to the region became easier, that more research was undertaken. The most extensive academic work on the area was done by Martin Vernier, Laurianne Bruneau and Quentin Devers over the last 20 years. But the reason Deshpande’s work is pioneering is because it documents the complexities of rock art in an accessible manner, bringing together elements of anthropology, history and travel. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

With no GPS markings, finding a site in Ladakh’s remote and monumental wastelands is unimaginably hard, says Deshpande, though she has an indispensable driver and enthusiastic collaborator in Jigmet Dorjey. “The light can fade any time and you are up on a thang (large stretches of barren land) with no idea which way to turn. Sometimes, it is hard to even find a site you have visited. You have to bank on mental mapping. There are days when I have returned with nothing in hand.”

| ||

| + | |||

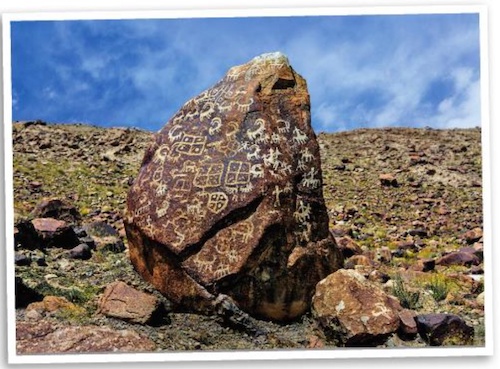

| + | There have also been rewards like the immense and striking piece that the photographer refers to as the ‘Stone Temple’ of Skindisa which stands at an uninhabited site in the Nubra valley. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

There are many undocumented etched rocks that Deshpande stumbled upon but she is not interested in being credited as their ‘finder’. “These are works of art a shepherd probably crosses several times every day. Why would I want to claim to have discovered them?” she says. For her, it is enough to offer readers a curated open-air museum through her visuals.

Deshpande’s photos will be shown at the Médiathèque Edmond Rostand in Paris from Nov 13 to Dec 31, 2024 | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Arts|R | ||

| + | ROCK ART: LADAKH]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|R | ||

| + | ROCK ART: LADAKH]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|ALPHABET | ||

| + | ROCK ART: LADAKH]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|R | ||

| + | ROCK ART: LADAKH]] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:11, 15 September 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

[edit] Rock Art

[edit] Ladakh: A potential for an Open Museum of Rock Art part 1

By Tashi Ldawa, Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Leh: Ladakh is getting more and more popular as a tourist destination. And why not: the peculiar landscape, the snow-capped mountains, the high altitude lakes, a different culture, the monasteries and so on make it an ideal tourist destination.

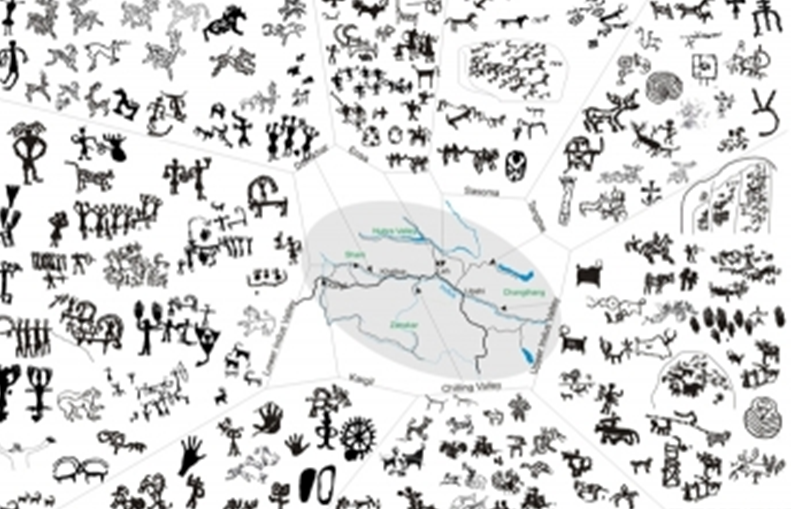

The rock art of Ladakh is one aspect which has a high potential for tourist attraction of a different nature altogether. Rock art is a heritage that we have inherited and many of these arts are more than 3-5 thousand years old. It is in fact the oldest monument to be found in Ladakh, far more than any monasteries. India is said to have third largest concentration of rock art in the world after Australia and Africa. Many of the rock art sites in the world, including India, have successfully tapped rock art as a tourist destination. The rock art of Ladakh (technically classified as petroglyphs) is so widespread throughout Ladakh that we can claim to have largest concentration of petroglyphs in India (if not world). In fact we feel Ladakh could serve as an open museum for rock art. More interestingly, there is a wide range in the subject and style to amaze any one. Many of the elements are Central Asian, while many resemble similarity with the ones found in Northern region of Pakistan and Tibet. So far we have discovered hundreds of sites, thousands of engraved rocks and tens of thousands of figures, throughout Ladakh.

While there are many universal messages in the rock art like celebration, ritual, tradition, hunting etc., yet many of the elements of rock art of Ladakh shows a rare exception in beauty, style and subject. Surely they display much more than archaeologist’s delight, it is worth a public display: for art or history. Given the fact of their antiquity, there is every scope of an open museum of rock art in Ladakh. But till anything is done, for the present, the message is “protect these rock art” they are part of our cultural heritage.

The collection of figure shows just a fraction of figures from different regions of Ladakh. I hope in future volumes I can write articles on rock art of Ladakh region-wise: keep watching.

Tashi Ldawa is an independent researcher on rock since last more than fifteen years. He has attended many national and international conferences on the subject and presently the only local expert on rock art. He is working for protection and conservation too. His book on rock art of Ladakh is likely to be published soon.

[edit] Rock Art of Lower Ladakh: Sham Part II

By Tashi Ldawa, Thursday, July 4, 2013

Leh: As I have already mentioned in the previous issue (Part I) that Ladakh has a rich source of rock art in the form of Petroglyphs, enough to be an ‘open museum’. One of the richest sites of rock art is along the river Indus. For convenience, we may divide it as lower and upper Indus, Leh being the dividing point. It depicts the earliest expressions of humankind. It is associated with cultural values. They are irreplaceable records of the artists, his thought and reason for the art he has drawn. Here in Ladakh it could play a vital role in understanding the role played by these mountainous regions as a cultural crossroads from the prehistory to the present day.

Phyang, Taroo, Umla, Basgo, Likir, Alchi, Nyurla all have some forms of prehistoric rock art. Some of the rocks in Basgo have been inundated due to the Alchi dam. One of the most important one with Kharoshti inscription near the Khaltse Bridge has been damaged. From Khaltse to Domkhar there are several sites worth noticing. Achinathang has some rock displaying human figures of rare representations. At Domkhar, particularly in the private compound of Thangjuk family lies one of the most beautiful forms of animal representations, a clear Central Asian art of more than two thousand years old. A scholar of rock art writes about this site as “This site is indeed a true gold mine for scientists and a possible key to better understand the ancient past of the lower Indus valley and thus potentially throw light on the ancient history of Ladakh, which up to present remains almost unknown”. There are also some Chinese inscriptions. The family has now made it a Rock Art Heritage Garden for visitors to enjoy. From Domkhar to Batalik there are another not less than dozen sites, each displaying some unique subject and forms. Near Bema, there is a large boulder with hundreds of figures, along with some Kharoshti inscriptions. At another site we have discovered pictograph (painting on the rock) which is rare to be found in Ladakh, it is yet to be studied in detail.

Only some of these rock art has been studied, and few of them have been dated to around three thousand BC. This cultural heritage as we have seen has been neglected and at many places they have been destroyed and damaged. We still have time to protect these rocks or else they may disappear forever. There are about half a dozen of scholars (foreigners) who are studying, but I feel, we as a Ladakhi have the responsibility to protect them and be proud of these rare and historically significant art: equally as any other monuments.

[edit] As in 2024

Malini Nair, August 18, 2024: The Times of India

From: Malini Nair, August 18, 2024: The Times of India

Ahtushi Deshpande is no stranger to the stunning trans Himalayan moonscape of Ladakh. As a solo trekker, she has traversed the landscape swept by broad brushstrokes of browns, beige, purple, white and turquoise several times. And revelled in its utter solitude and surprising finds.

None of it, however, prepared the writer and photographer for the spectacle at Kawathang, 100 km from Leh where, standing out against the dark patina of worn rocks were etchings — beautiful, spare, mysterious and abstract. Especially intriguing were the delicate hand impressions, elongated fingers stretching upward.

What were they trying to say across at least 5,000 years? Did they mark a tribe, an identity, or were they a sign of welcome? In an obsessive quest over 13 years and 18 journeys, Deshpande has documented more than 200 such sites across Ladakh. They can be found along the riverine stretch of the Indus which runs for 400 km through Ladakh as well as along ancient trails. Some are simply parked in the middle of nowhere on vast desertic stony flats.

It is a formidable project — the terrain is inhospitable and mind-bogglingly vast and temperatures can drop to minus 40 degrees C in winters while summers stay bone dry. But the etchings and the stories they tell, says the 55-year-old, were irresistible. “They are big outdoor museums of rock art, all done in situ, on the toughest and most ungiving canvas there can be. It made me realise that we have forgotten how hardy and resilient we can be as a human race,” she says.

Some petroglyphs, as etched rocks are called, are known, some are hidden, and some simply a part of the mountain landscape that shepherds pass without a second look. There are hunting scenes on these rocks, rites of passage, scenes from community life, celebratory dancing and, of course, animals, most notably the ibex, a wild goat with dramatically arched horns. These densely engraved spare stick figures, which show great artistry, sophistication and imagination, have been captured in a stunningly illustrated book by Deshpande titled, ‘Speaking Stones: Rock Art of Ladakh’.

There is an urgency to the work. Unlike cave art, which is still protected by its shelter dwelling, Ladakh’s petroglyphs stand open to the elements, and vulnerable to human interference. “Even in the 13 years I have travelled, I have seen rocks disappear, either into the waters or felled for road construction or painted over by graffiti or signage,” says Deshpande, stressing the need to preserve these ‘ancient canvases’.

There are two journeys subsumed in Deshpande’s quest: one through the rarified air of Ladakh and the other through the fragility of life itself. She is a three-time breast cancer survivor, and the disease arrived four years after her Ladakh quest began. But she would rather not let what she calls “an errant cell” overcome the narrative on her book. “Cancer divides your life into two — the one before and the one after diagnosis. But Ladakh gave me the purpose to keep going instead of allowing the fear to overwhelm me. I am alive today and that is all that counts,” she says, and this is a philosophy that also defines her work with cancer support groups.

The earliest explorations of the petroglyphs began in 1905 with archaeologist August Hermann Francke but it was not until the 1980s, when access to the region became easier, that more research was undertaken. The most extensive academic work on the area was done by Martin Vernier, Laurianne Bruneau and Quentin Devers over the last 20 years. But the reason Deshpande’s work is pioneering is because it documents the complexities of rock art in an accessible manner, bringing together elements of anthropology, history and travel.

With no GPS markings, finding a site in Ladakh’s remote and monumental wastelands is unimaginably hard, says Deshpande, though she has an indispensable driver and enthusiastic collaborator in Jigmet Dorjey. “The light can fade any time and you are up on a thang (large stretches of barren land) with no idea which way to turn. Sometimes, it is hard to even find a site you have visited. You have to bank on mental mapping. There are days when I have returned with nothing in hand.”

There have also been rewards like the immense and striking piece that the photographer refers to as the ‘Stone Temple’ of Skindisa which stands at an uninhabited site in the Nubra valley.

There are many undocumented etched rocks that Deshpande stumbled upon but she is not interested in being credited as their ‘finder’. “These are works of art a shepherd probably crosses several times every day. Why would I want to claim to have discovered them?” she says. For her, it is enough to offer readers a curated open-air museum through her visuals. Deshpande’s photos will be shown at the Médiathèque Edmond Rostand in Paris from Nov 13 to Dec 31, 2024