Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Tribes

(→Uncontacted tribes, India and the world) |

(→The main tribes) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

And, as the police considers retrieving Chau’s body, it should not compound his error by going to the island or inviting a confrontation, “further contact could be absolutely lethal”, warns Mukerjee. | And, as the police considers retrieving Chau’s body, it should not compound his error by going to the island or inviting a confrontation, “further contact could be absolutely lethal”, warns Mukerjee. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Shompen and the Great Nicobar Project= | ||

| + | ==As of 2024== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.indiatimes.com/article-share?article=14_10_2024_016_026_cap_TOI BKP Sinha & Arvind Kumar Jha, Oct 14, 2024: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Deep within Great Nicobar Island forests live the Shompen tribe, classified as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Traditionally hunter-gatherers, their lives revolve around forests, rivers and wildlife, their diet a range of forest foods, wild animals and crops such as pandanus, lemon, and colocasia. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Recognising the significance of preserving their right to life and livelihood, the 1991 amendment to the Indian Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, despite enforcing a nationwide ban on hunting, safeguarded Shompen’s traditional hunting rights, specified in the A&N administration’s notification of April 28, 1967. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Traditional knowledge | Surveys on Shompen show their lifestyle, rites, rituals, and practices are linked intricately to the natural world, forming a unique repository of traditional knowledge systems. In their social structure, community is supreme and family, the smallest unit, their economy subsistence-based. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Indian Journal of Medical Research in its March 2024 publication documented that Shompen have a robust ethnomedicine system that uses resources from the wild. This indicates the richness of biodiversity as also uniqueness of their indigenous knowledge. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Lands lost, health ruined | An area of 1,044.5 sq km was declared a reserve for these indigenous people in 1957. This gradually shrank to 853.2 sq km with encroachment by outsiders, despite protective measures under the A&N (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956. Significant influx since 1969 was exacerbated by construction of a 43km East-West Road through Shompen territory, impacting also their cultural fabric.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | While the population of outsiders grew steadily, numbers of Shompen fluctuated: 131 in 1991, 398 in 2001, and 229 in 2011. Their nomadic and hunter-gatherer lifestyle combined with an aversion to external interference is cited as a major reason for these fluctuations. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Destruction of habitat is undermining Shompen’s local health tradition. Nutritional mix provided by wild foods (fruits, tubers, honey, fish, and game) has deteriora- ted. Shompen’s health and nutrition survey 2024 showed chronic undernutrition. High stunting rates were observed in 63% children; 33% children were underweight. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Legally protected | The Scheduled Tribes and Other Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, familiar as FRA, defines the community tenures of habitat and habitation as a ‘forest right’. It favours primitive tribal groups and pre-agricultural communities. For Shompen, their habitat is the space where their bio-culturally evolved life and traditional institutions coexist. Shaped over centuries, their habitat has nurtured a unique lifestyle, livelihood system, culture, economy, and worldview. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Sections 3(1)(e) and 4(1) of FRA, in particular, provide for the recognition of habitat rights of forest dwelling STs like the Shompen. FRA also facilitates their recognition by defining hamlets as a ‘village’. Further, a gram sabha that initiates the recognition process can consist of a village’s all adult members, rather than voters. Accordingly, processing of ‘habitat rights’ cases as also those of access to biodiversity, intellectual property and traditional knowledge, was easily possible. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Safeguards diluted | Per the tribal affairs ministry website, FRA implementation in A&N Islands has been limited to setting up committees and organising awareness programmes. Instituting a state-level monitoring committee and training of officials hasn’t been done. While it says Shompen have rights under the A&N (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956 in the tribal reserve notified as reserve forests & protected forest reserve, a Jan 2022 report, for the first time, enters a ‘Nil’ figure under progress to date. | ||

| + |

Thus, their forest rights and Shompen’s opportunity at empowerment under FRA Section 5 are disregarded. The ‘Nil’ figure also makes their gram sabhas virtually inconsequential in future diversions of their habitat. | ||

| + |

Then the construction | Compounding these issues is the looming threat posed by the Great Nicobar Island (GNI) Project. Valued at ₹72k cr, the project includes a port, a greenfield airport, and other infra constructions. The project deserved stricter scrutiny of environmental and FRA compliance, poised as it is to severely impact Shompen’s already fragile habitat. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The project area overlaps with a Unesco biosphere reserve, nesting grounds for leatherback turtles, habitat of the vulnerable Nicobar megapode, and CRZ 1A areas (ecologically sensitive areas part of Coastal Regulation Zone, which regulates industrial activity near coastlines).The proposed felling of an estimated 1mn trees puts at risk both the Shompen and the island’s biodiversity. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Recognise their rights | Unless Shompen’s statutory rights are recognised and adequately protected, any action with such adverse impact on their habitat amounts to gross injustice. Consequences could be catastrophic, potentially rendering the Shompen as ‘ecological refugees’, just like the Pardhi tribe subsequent to the total ban on hunting in 1991. Historical precedents should serve as stark reminders of the perils of disregarding indigenous peoples’ rights and conservation practices. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Shompen’s survival and prosperity requires an inclusive approach that respects their rights and protects their habitat while acknowledging the importance of island’s ecological uniqueness. Destruction of their habitat and pressures of large-scale development demand urgent action to recognise Shompen’s statutory rights and preserve pristine natural resources. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Sinha is former principal chief conservator of forests (PCCF), UP. Jha is former PCCF & commissioner (tribal department), Maharashtra. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Andaman And Nicobar Islands|T ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Communities|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

=Uncontacted tribes, India and the world= | =Uncontacted tribes, India and the world= | ||

| Line 139: | Line 186: | ||

[[Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Flora]] | [[Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Flora]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Andaman and Nicobar: Hindus, Hinduism]] | ||

[[Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Natural calamities]] | [[Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Natural calamities]] | ||

| Line 165: | Line 214: | ||

ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

[[Category:Places|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | [[Category:Places|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Andaman And Nicobar Islands|T ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Communities|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

| + | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|A ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBESANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES | ||

ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS: TRIBES]] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:04, 21 December 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] The main tribes

[edit] A backgrounder

Why the Sentinelese choose solitude even 60,000 years on, November 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Why the Sentinelese choose solitude even 60,000 years on, November 26, 2018: The Times of India

From: Why the Sentinelese choose solitude even 60,000 years on, November 26, 2018: The Times of India

What are the original tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands?

There are six original tribes in this archipelago of 572 islands spread over the Bay of Bengal from Land Fall Island in the north to the Great Nicobar Island in the south. Four of these — Great Andamanese, Onge, Jarawa and Sentinelese — are Negrito, dark-skinned ethnic groups who inhabit parts of south and southeast Asia. Survival International, a rights group for indigenous and uncontacted peoples, estimates Negrito tribes arrived in the Andamans from Africa up to 60,000 years ago. There are also two Mongoloid tribes — the Shompen and Nicobarese — who likely came from the Malay-Burma coast and have lived on Nicobar islands for thousands of years.

Are they all hostile to outsiders?

The first modern settlement of outsiders was established in 1789 by Lt. Blair at Chatham Island, now part of Port Blair. The settlers faced hostility from the start. The most determined effort to push out the British was the 1859 Battle of Aberdeen. But locals with bows and spears were no match for modern British troops. When the Britishers arrived, there were more than 5,000 Great Andamanese. After the battle and “mainstreaming”, they number 44 today. The Onges met a similar fate; from 670 in 1900 their population has declined to 101 today. The Jarawas, hostile till 1998, have been relatively successful in maintaining their population. But experts believe their condition has worsened after increased interaction with outsiders. In 1999 and 2006, Jarawas suffered outbreaks of measles, which has wiped out many indigenous tribes worldwide. Tourism has also led to exploitation, including sexual abuse of Jarawa women. Experts say the Sentinelese could be hostile to outsiders because of similar incidents.

What is the religious composition of these tribes?

Of the six original tribes, the overwhelming majority follow their original religions, which are largely unknown to us. The Nicobarese are the only tribe that follow mainstream religions and Christianity is the most popular. Some experts believe that the success of Christianity could have been the trigger for missionaries like John Allen Chau, whose attempt to interact with the Sentinelese has received widespread criticism.

What is their population?

It is difficult to have a normal house to house census for remote and hostile tribes like the Sentinelese, and so estimates have a wide range. Official data from census 2011 estimates the Scheduled Tribe population of the islands at 28,530. The overwhelming majority are the Nicobarese. Among the six original tribes, the Jarawas are a distant second while the Sentinelese constitute the smallest group.

[edit] … and their fears

From: November 24, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The main tribes of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands… and their fears

[edit] Contacts of outsiders with Andaman, Nicobar Tribes

Amulya Gopalakrishnan, November 25, 2018: The Times of India

From: Amulya Gopalakrishnan, November 25, 2018: The Times of India

Whatever combination of recklessness and zeal possessed John Allen Chau, American adventurer and Christian missionary, to land on North Sentinel Island, with a football and a Bible, it didn’t end well. He wanted to “declare Jesus” to one of the last uncontacted tribes on earth.

But far from saving their souls, Chau presented a threat to their lives. The North Sentinelese are among the only surviving direct descendants of the first humans in Asia. In their 50-square-km island in the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, they have lived apart from others for millennia. Raining arrows upon anyone who comes too close like Chau, they obviously want to keep it that way.

This makes sense since their long isolation has left them with no immunity to our germs. Contact with outsiders has been destructive to other indigenous communities in the Andamans — whether through colonial raids or civilising missions, settlers encroaching on their land and exploiting their resources, anthropologists bearing gifts or tourists throwing scraps of food, it is the others who have never left them alone.

“They have been on those islands anywhere between 20,000 and 40,000 years, and they’ve done fine without us. The Andamans would not have been a part of India if not for British colonisation, and that logic continues to operate even now. It became a convenient place to move refugees from Bangladesh. There has been no consideration of the native inhabitants, or water shortages or how fragile the island ecology is,” says Madhusree Mukerjee, author of ‘The Land of Naked People’, a book about the indigenous islanders.

The Andaman islands are home to four aboriginal tribes, who have been here for tens of thousands of years, long before the British, the Japanese or Indian presence. Each of these is a different story of clumsy external interventions. The Great Andamanese, the first to encounter outsiders, numbered around 5,000. In less than a century after the British established a penal colony, their numbers dwindled drastically as they succumbed to diseases like measles and syphilis. Now there are barely 50 of them, remnants of a lost culture, living on Strait Island. Entire languages, and the secret things they contained, have disappeared. “They are like lost souls, misfits who belong neither to our society nor what they used to be a 100 years ago,” says Anvita Abbi, a linguist who has studied the disappearing languages of the Great Andamanese.

The Onge too, in Little Andaman island, have been battered by an alien culture. After the British and the Japanese, it was the Indian state that settled mainlanders and refugees in the islands, clearing forests for plantations, farmland and settlements — making it harder for the Onge to access wild pig and dugong, spreading disease, inflicting heavy social pressure. They would be given bottles of alcohol, in exchange for precious resources like honey, resin, ambergris and turtle eggs. “We occupied and settled areas, confined them to a small space in a tribal reserve,” says Denis Giles, editor of the Andaman Chronicle. Now, with logging and poaching destroying their habitat and their way of life, “they totally depend on provisions we supply,” he says.

Only the Sentinelese, confined to their island, and not in the way of anyone else’s ‘development’, have successfully kept their distance. The Jarawas, whose space is surrounded by settled areas, and was cleaved by the Andaman Grand Trunk Road, have had decades of interactions with outsiders — an encounter that has been fraught by all accounts — from hostility to a partial softening by the late 1990s, and even forays into the society outside. ‘What have we given back? All kinds of diseases, sexual exploitation, poaching their resources,” says Giles. In recent years, video clips of Jarawa girls made to dance for policemen and tourist safaris had gone viral. “The Jarawas are in transition, there may be generational differences among them, when it comes to contact with outsiders – but it should be entirely their choice,” says Mukerjee.

Despite laws like the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (1956), and Andaman Adim Janjati Vikas Samiti, a special policy for Jarawas framed in 2004 and a dedicated protection police, the spirit is weak when it comes to implementation. “In spite of so many cases registered, brought before the magistrate, the offenders are released on bail. Not even one person has been punished for breaking these laws, says Giles.

Cultural protection can’t be disentangled from ecological protection, says Pankaj Sekhsaria, scientist, environmentalist and writer. “These indigenous communities have the first right on land and resources, which the government of India has failed to recognise.” It is hard for them to survive when the forests, which their lives and practices are bound up with, are destroyed. “The 1,000 square kilometres of the Jarawa tribal reserve, for instance, holds the last of the remaining original evergreen forest of the Andamans, and it is more biodiverse than any wildlife sanctuary in these parts,” he points out.

All too often, the needs of the settlers and their economic aspirations have been expressed in a desire to “mainstream” and “integrate” indigenous people like the Jarawas, who are regarded as ‘Indian citizens’. This is just ignorant and racist, says Mukerjee, without an attempt to understand the indigenous people themselves. Their idea of the good life, their knowledge, their social and spiritual values are not the same as those of their neighbours. “What can you teach them? About Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Narendra Modi? How could that be meaningful in their lives,” asks Giles.

All ‘tribes’ cannot be painted with the same brush, says Abbi — the Andamanese tribes are entirely different from the central Indian groups or even the Nicobarese. “How can a society jump ahead tens of thousands of years?” More importantly, why should it? They know things we don’t — about fish, seashells, how to survive. Not one of them died during the 2004 tsunami, because they knew how to read the signs. “What does assimilation mean, they are already assimilated into their environment, and we are not,” says Abbi. While compiling her dictionary of the Great Anadamanese languages, she discovered they didn’t have a word for rape or sexual assault, but now they are painfully aware of what it means, having been attacked by outsiders.

We have to get beyond our own frames to appreciate human diversity, rather than interfere and assume that everyone wants what we want. For instance, the Jarawas orient themselves by the light and shade of the forest, according to the anthropologist Visvajit Pandya —this lightscape is crucial to their social order. If your daily practices involve stars and fireflies, and you dread intense heat and light — then wouldn’t it make sense that electric lightbeams are registered as an assault, not an amenity? In other words, your vision of development isn’t necessarily the same as theirs.

Now, there has been a grand push for tourism in the Andamans, floated by the Niti Aayog, which seems to assume that the islands are virgin territory, to be made over at will. Restricted area permits were removed from several islands, including North Sentinel and Little Andaman. “Of the many islands in the Andamans that might be suited for tourism, why pick those most vulnerable, which are home to indigenous groups?” asks Giles.

And, as the police considers retrieving Chau’s body, it should not compound his error by going to the island or inviting a confrontation, “further contact could be absolutely lethal”, warns Mukerjee.

[edit] Shompen and the Great Nicobar Project

[edit] As of 2024

BKP Sinha & Arvind Kumar Jha, Oct 14, 2024: The Times of India

Deep within Great Nicobar Island forests live the Shompen tribe, classified as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Traditionally hunter-gatherers, their lives revolve around forests, rivers and wildlife, their diet a range of forest foods, wild animals and crops such as pandanus, lemon, and colocasia.

Recognising the significance of preserving their right to life and livelihood, the 1991 amendment to the Indian Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, despite enforcing a nationwide ban on hunting, safeguarded Shompen’s traditional hunting rights, specified in the A&N administration’s notification of April 28, 1967.

Traditional knowledge | Surveys on Shompen show their lifestyle, rites, rituals, and practices are linked intricately to the natural world, forming a unique repository of traditional knowledge systems. In their social structure, community is supreme and family, the smallest unit, their economy subsistence-based.

Indian Journal of Medical Research in its March 2024 publication documented that Shompen have a robust ethnomedicine system that uses resources from the wild. This indicates the richness of biodiversity as also uniqueness of their indigenous knowledge.

Lands lost, health ruined | An area of 1,044.5 sq km was declared a reserve for these indigenous people in 1957. This gradually shrank to 853.2 sq km with encroachment by outsiders, despite protective measures under the A&N (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956. Significant influx since 1969 was exacerbated by construction of a 43km East-West Road through Shompen territory, impacting also their cultural fabric.

While the population of outsiders grew steadily, numbers of Shompen fluctuated: 131 in 1991, 398 in 2001, and 229 in 2011. Their nomadic and hunter-gatherer lifestyle combined with an aversion to external interference is cited as a major reason for these fluctuations.

Destruction of habitat is undermining Shompen’s local health tradition. Nutritional mix provided by wild foods (fruits, tubers, honey, fish, and game) has deteriora- ted. Shompen’s health and nutrition survey 2024 showed chronic undernutrition. High stunting rates were observed in 63% children; 33% children were underweight.

Legally protected | The Scheduled Tribes and Other Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, familiar as FRA, defines the community tenures of habitat and habitation as a ‘forest right’. It favours primitive tribal groups and pre-agricultural communities. For Shompen, their habitat is the space where their bio-culturally evolved life and traditional institutions coexist. Shaped over centuries, their habitat has nurtured a unique lifestyle, livelihood system, culture, economy, and worldview.

Sections 3(1)(e) and 4(1) of FRA, in particular, provide for the recognition of habitat rights of forest dwelling STs like the Shompen. FRA also facilitates their recognition by defining hamlets as a ‘village’. Further, a gram sabha that initiates the recognition process can consist of a village’s all adult members, rather than voters. Accordingly, processing of ‘habitat rights’ cases as also those of access to biodiversity, intellectual property and traditional knowledge, was easily possible.

Safeguards diluted | Per the tribal affairs ministry website, FRA implementation in A&N Islands has been limited to setting up committees and organising awareness programmes. Instituting a state-level monitoring committee and training of officials hasn’t been done. While it says Shompen have rights under the A&N (Protection of Aboriginal Tribes) Regulation, 1956 in the tribal reserve notified as reserve forests & protected forest reserve, a Jan 2022 report, for the first time, enters a ‘Nil’ figure under progress to date. Thus, their forest rights and Shompen’s opportunity at empowerment under FRA Section 5 are disregarded. The ‘Nil’ figure also makes their gram sabhas virtually inconsequential in future diversions of their habitat. Then the construction | Compounding these issues is the looming threat posed by the Great Nicobar Island (GNI) Project. Valued at ₹72k cr, the project includes a port, a greenfield airport, and other infra constructions. The project deserved stricter scrutiny of environmental and FRA compliance, poised as it is to severely impact Shompen’s already fragile habitat.

The project area overlaps with a Unesco biosphere reserve, nesting grounds for leatherback turtles, habitat of the vulnerable Nicobar megapode, and CRZ 1A areas (ecologically sensitive areas part of Coastal Regulation Zone, which regulates industrial activity near coastlines).The proposed felling of an estimated 1mn trees puts at risk both the Shompen and the island’s biodiversity.

Recognise their rights | Unless Shompen’s statutory rights are recognised and adequately protected, any action with such adverse impact on their habitat amounts to gross injustice. Consequences could be catastrophic, potentially rendering the Shompen as ‘ecological refugees’, just like the Pardhi tribe subsequent to the total ban on hunting in 1991. Historical precedents should serve as stark reminders of the perils of disregarding indigenous peoples’ rights and conservation practices.

Shompen’s survival and prosperity requires an inclusive approach that respects their rights and protects their habitat while acknowledging the importance of island’s ecological uniqueness. Destruction of their habitat and pressures of large-scale development demand urgent action to recognise Shompen’s statutory rights and preserve pristine natural resources.

Sinha is former principal chief conservator of forests (PCCF), UP. Jha is former PCCF & commissioner (tribal department), Maharashtra.

[edit] Uncontacted tribes, India and the world

The last few remaining Sentinelese, believed to number around 15, have come into the limelight following the death of American preacher-traveller John Allen Chau on November 17, 2018 in the patch of Andaman Islands populated by them.

But there are are plenty of other tribes that live in majestic isolation.

MORE THAN 100 UNCONTACTED TRIBES

Like the Sentinelese, according to estimates, there are more than 100 uncontacted groups around the world, mostly in the densely forested areas of South America and New Guinea, such as Awá (Brazil), Papuan tribes (West Papua), Mashco Piro (Peru) and Kawahiva (Brazil).

From: The Times of India

From: The Times of India

THE ENDANGERED

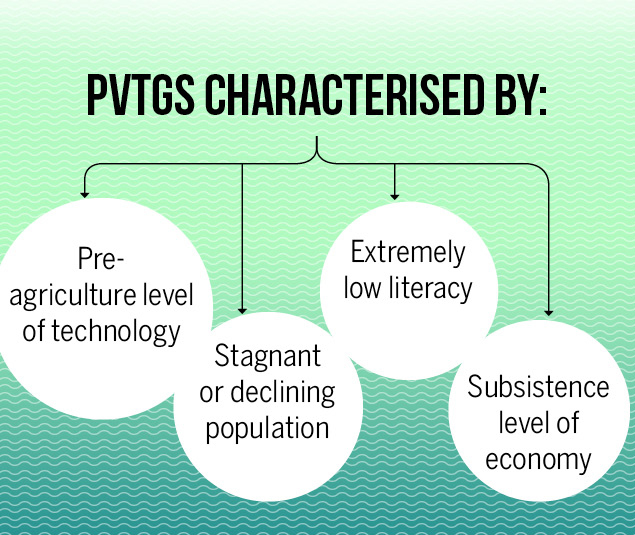

India too is home to hundreds of indigenous people and tribes, of which 75 are classified as Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs)

From: The Times of India

DWINDLING NUMBERS

From: The Times of India

From: The Times of India

From: The Times of India

REMOTE HABITATS

These groups generally inhabit isolated, remote and difficult areas, ranging from plains and forests to hills. The Sentinelese inhabit the small North Sentinel Island (60 sq. km.) and because of the geographical separation from other islands, they have maintained strict isolation from the rest of the world. It is illegal to make contact with the tribe although curbs on visiting the tiny island were lifted in August 2018.

From: The Times of India

The Jarawas of the Andaman islands saw their land split in two when the administration built a highway (Andaman Trunk Road) through their territory, which is now being used by settlers, tourists and poachers targeting their reserve.

From: The Times of India

From: The Times of India

From: The Times of India

THE WAY FORWARD

Development has not reached several tribes, but many do not want it either. A fine balance between development and respecting the rights, culture, traditions and privacy of these people is required.

[edit] See also

Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Fauna

Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Flora

Andaman and Nicobar: Hindus, Hinduism

Andaman And Nicobar Islands: Natural calamities

Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Parliamentary elections

Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Tribes

Census India 1931: The Population Problem in Andaman and Nicobar Islands