Armenians in India

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> </div> |} [[Category:Ind...") |

(→History) |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | =History= | ||

| + | ==As of 1895== | ||

| + | This section is an extract from | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |||

| + | |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | ||

| + | '''THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL.''' <br/> | ||

| + | By H.H. RISLEY,<br/> | ||

| + | INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE, OFFICIER D'ACADÉMIE FRANÇAISE. <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ethnographic Glossary. <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CALCUTTA: <br/> ''Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press.''<br/> 1891. .</div> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all. | ||

| + | |||

| + | NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, [http://www.facebook.com/Indpaedia Indpaedia.com]. All information used will be duly acknowledged. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =Armenians= | ||

| + | IN 1605 Shah 'Abbas invaded Armenia, and transferred 12,000 inhabitants of Julfa, on tbe Araxes, to the neighbourhood of Ispahan, where he allotted them land on the banks of the Zindarud, which subsequenty became the site of a town, since known as New Julfa. While Shah 'Abbas lived, he treated the settlers with remarkable liberality, advancing money without exacting interest, granting the free exercise of their religion, and permitting them to elect a "Kalan-tar." or headman, of their own. No Muhammadan was allowed to reside within the walls, and, as the murder of an Armenian could only be expiated by the rigorous law of retaliation, the inhabitants were respected, and favoured, by the Persians themselves. During the reign of Shah Hussain (1694-1722), however, many of these privileges were repealed, and the slayer of an Armenian was absolved from all punishment on payment of a load of corn. The prosperity of the settlement was destroyed by Shah Mahmud and the Afghans in 1722, but not until after a gallant though unavailing resistance.1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | stone of one Khwajah Martinas, who died in 1611.1 It was, however, into Western India that Armenians chiefly congregated. In 1623 Pietro della Valle found the Dutch intermarrying with them; and in 1638 Mandelslo encountered Armenians in Surat and Gujarat. Tavernier,2 moreover, has preserved the name of one Corgia, brought up by Shah Jahan, an excellent wit and poet, much in the King's favour, who had conferred on him many fair commands, though he could never by threats or promises win him to turn Muhammadan. Bender, too, mentions Armenians in Delhi, who were ruining the inland trade of the Dutch by their competition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If Mr. Glanius is to be relied on, a body of Armenian cavalry, celebrated for its horses and discipline, accompanied the army of Mir Jamlah, in 1662, when he invaded Assam. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Towards the end of the seventeenth century many Armenians resided at Chinsurah, and they possessed "a pretty good garden" opposite Calcutta.. During the latter days of Muhammadan rule the principal Armenian settlement in Bengal was at Saidabad, near Murshidabad, whence were annually exported valuable assortments of piece goods and raw silk. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Armenians have always been distinguished as enterprising traders throughout Asia, and as early as 1690, when the East India Company was entering upon its marvellous career, Mr. Charnock received3 instructions to employ them to sell the annual shipments in the interior, and buy fine muslins and other valuable goods. The ostensible reason for this preference being that they could transact business with the native traders better than agents of the Company provided with a firman.3 In 1694, again, a proposal was made to the Armenians of Ispahan to sell the goods of the Company, or barter them for silk, money, and "Caramania wool;" but this project failed, as the Armenians themselves imported, by Aleppo, the goods of the Turkey Company. During the eighteenth century, the Armenian community in Bengal prospered, and, favoured by many special grants from the Imperial court, secured much of the inland trade of the province. Several individuals raised themselves to positions of eminence during the civil wars preceding the overthrow of the Mughal power. Coja (Khwajah) Gregory, better known as Gurghin Khan, commanded the artillery of Mir Qasim at the battle of Gheriah, in August, 1763; while his brother, Coja Petrus, or Petrus Arrathoon, was still more intimately connected with the early struggles of the Company, being as Gumastha, or agent, of both Sirajuddaulah, and Mir Qasim, mixed up with many of the intrigues of that eventful period. The latter survived till 1782, when he died, leaving great wealth. At this time the Armenians were often charged, but probably without sufficient reason, with being turbulent and crafty, and doing much injury by thwarting the policy of the English Company. In spite of this accusation, however, they were permitted to reside in Calcutta in 1758; but an order forbidding their dwelling in the smaller factories was in force as late as 1765. The Court of Directors, regarding this busy people as the pioneers of commerce, issued an order that whenever a certain number congregated together, an Armenian church should be built for them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The history of the Armenian colony at Dacca has not been preserved. It is stated, on doubtful authority, that when Job Charnock returned to Calcutta in 1698, he invited the Armenian merchants in Dacca to settle in the new town; but the first authentic record is a time-worn tombstone in the old churchyard of Tezgaon, which marks the grave of one Avitis, an Armenian trader, who died on the 5th August, 1714. At the middle of the eighteenth century Armenians, as well as Europeans, were extensively engaged in the slave trade, and if we judge of the morality of the time by that described by one of their number, the standard was not a high one. In 1747 a rich Armenian died at Dacca without heirs, and to prevent the estate lapsing to the Nawab, the narrator consented to come forward as a son of the deceased. The perjury is justified on the plea that it prevented "wild beasts from eating the flesh of lambs."1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the census of 1866 there were 703 Armenians resident in Calcutta, while on the 6th April, 1876, they numbered 707. In 1872, again, the Armenian population of Bengal proper was only 875, and of that number 710 resided in and around Calcutta, and 113 in Dacca. Mr. I. G. Pogose, in 1870, estimated the Dacca Armenians at 107, of whom 36 were males, 23 females, and 48 children. The professions and occupations of the males were as follows: one was a priest, five landholders, three merchants, one a barrister, five shopkeepers, seven shopmen, and four Government servants. Until comparatively recent times no Armenian could hold land; but under the Muhammadan rule many were farmers of the revenue and executive officers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The causes which have checked the growth of the Armenians in Eastern India have been recapitulated by a writer in the Calcutta Review,2 who points out that the early settlers were robust, energetic, and frugal men, devoting their whole time and thoughts to trade, while their descendants, lacking many of the peculiar traits of the race, have sadly degenerated. Separation from home influences, and association with alien races, effected a marked change of habits, and, resisting the introduction of European customs, they insensibly adopted many Indian ones. The indolence, moreover, induced by a hot, uncongenial climate, along with a rooted aversion to physical exertion, promoted habits of immorality and intemperance. Early marriages became fashionable, the offspring growing up sickly and tainted by disease. In-breeding still further impaired the race, and only those families who sought or brides in distant cities, or among immigrants from Persia, have inherited the muscular healthy constitutions of the parent stock. As late as a generation ago the Armenians of India were generally illiterate, being totally ignorant of European literature. They spoke and often read Armenian, they conversed fluently in Persian, Urdu, and Bengali; but they were unacquainted with the English language. Of late years, however, although Armenian is till the language of their homes, English is spoken universally, and an English education is considered indispensable. The English costume, too, is always worn, and the national dress is only seen on festive occasions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The modern Armenian is proverbially hospitable, while his open-handed charity to the poor of all creeds, his benevolence, and sympathy for the destitute and unfortunate of his own faith, and his kindness to his native servants and acquaintances, excite the admiration of his fellow townsmen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Catholicos, or Patriarch, of the Armenian church resides at Echmadzin, in Russian Armenia. Not only is he the Primat, but his monastery is the centre where pilgrims join in fraternal union with their brethren of other lands, and from which the Chrism, or holy oil, is brought for the services of the church in the East. The Bishop of Julfa has jurisdiction over all the Armenian churches in India, and by him the priests are inducted, or translated. India has so few attractions for the priesthood, that livings in that country, it is said, can only be got by an offering of twenty Tomans, equivalent to ten guineas. The priests met with in India are always married men, whose wives and families remain at Julfa, as hostages for their return. Five years is the fixed period of their residence, but on application a transfer to another church is often obtained. The greatest objection to this system is, that new arrivals can only converse in Persian and Armenian, while their flock speak Armenian, rarely Persian. Having acquired the vernacular, they are transferred to Singapore, or China, where another language has to be learned, under the same discouraging circumstances. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The position of an Armenian priest in India is an unenviable one. Separated from all his dearest ties, he finds himself in a small community stirred by the influences of strange races, and rival faiths, and dependent on the goodwill and liberality of his brethren. Services, beginning before daybreak, and lasting for six or seven hours, at which the congregation only attend towards the end; fasts twice every week, and during Lent continuing for weeks, tell upon the strongest constitutions. But the interest shown in the spiritual welfare of his flock, the sympathy shown to the sick and dying, and their moral, and generally blameless, lives, are the bonds which bind and endear them to their people. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The four great festivals of the Armenian church are the Nativity, Ascension, Annunciation, and that observed in honour of St. George. These festivals, as in the Greek church, are kept according to the old style; for instance, the Nativity, along with the Epiphany, on the 6th January. The Assumption, however, celebrated by the Greek and Latin churches on the 15th Ausgust, is commemmorated by the Armenian on the Sunday between the 12th and 18th of that month. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The dogmas, rites, and practices of the Armenian church in India1 are identical with those of the parent establishment, being uninfluenced by contact with other Christian churches, but several customs are followed which are not mentioned by writers on such matters. Thus, on the Assumption, raisins wrapped in coloured paper are distributed in the church; and until late years a large pile of dry grass was collected near the church door on Ash Wednesday, and at a certain part of the service the congregation, carrying lighted tapers, defiled out of the building, and set fire to it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At Easter and Christmas, after service, the priest visits each household, presenting the goodman with a cake of unleavened bread, in return for which he receives a fee, and his attendants wine, sweetmeats, and dyed eggs. Although they disbelieve in the purgatory of the Roman Church, Armenians admit that the spirits of the dead remain till the Day of Judgment in Paradise, or a place of probation. During Christmas and Holy Week, therefore, incense and wax tapers are forwarded to the priest who performs a service at the grave of the deceased relatives. Armenians are forbidden, like the Jews and Muham- | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1 For interesting particulars regarding this Christian Sect, see "Histoire, Dogmes, Traditions et Liturgie de l'Eglise Armenienne Orientale." Par E. Dulaurier, Paris, 1855. | ||

| + | |||

| + | madans, to eat blood or things strangled, and on Christmas and Easter the flesh eaten must have been killed by a Christian, and a godfather. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The public declaration of vows is one of the most solemn ceremonies of the Armenians. The person vowing presents the priest with two wax candles and two rupees for each pledge. Two gilt hands with the forefingers and thumbs united, the other fingers extended and adorned with jewels, being taken from the altar are dipped into holy water, and the lips of all present touched, whils the witness kneeling rests his forehead on the floor. The priest, after repeating certain prayers, holds the two hands over the people and blesses them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Armenians esteem the "Little Gospel" as only second in value to the Bible itself, and are fond of detailing incidents recorded in it. This uncanonical scripture is the "Historia de Nativitate Mariae et de Infantia Salvatoris."1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Last century the Armenians observed many Persian, Bengali, and European customs. The dress of the men consisted of a Persian vest, or Jamah, fastened with a belt (Patka), and loose trousers. Their head-dress was a black brimless hat, about eight inches high. The costume of the women resembled that of the men, but the vests were longer. They wore the hair hanging down loose behind, adorned with strings of pearls, and other gems, and covered with a hat, called Kambhara. Moreover, their teeth were stained with Misi, the hands and feet with Menhdi. It was considered indecorous and improper for the women to speak to, or appear before men in public, and, like the Muhammadan wife, the Armenian had to endure great hardships when most requiring sympathy, the doors and windows of her room were carefully closed against evil spirits for forty days, a fire was kept burning on the threshold, and no one dared to enter the room till mustard seed had been cast on the embers. As a further protection the child was arrayed with strings of amulets and charms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The amusements of the men were confined to kite-flying, in which pastime much money was lost and won, and to the fighting of rams and game cocks. Native music was, and still is, preferred to European, and dinner parties wound up with "Nach" dancing and singing. At meals tables were not used, but mats and carpets being spread, the guests squatted and ate with their fingers. The Armenian cuisine more nearly resembles that of the Muhammadans than the English, and at feasts the variety of dishes is so embarrassing that the etiquette requiring each guest to taste of every dish becomes positively dangerous. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''1 Giles' "Uncanonical Gospels." London, 1852.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''1 "The Life and Adventures of Joseph Emin, and Armenian." London, 1792.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''2 "The Armenian in London Physically considered," vol. xxx, June, 1858.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''1 "J.A.S." of Bengal, August, 1874.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''2 "Voyage," Liv. i, c. 7.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''3 "Annals of the E.I. Company," iii, 88, 160.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Armenian marriages are ordinarily negotiated by the parents, or guardians. A few days before the wedding the hands and feet of the bride are stained with Menhdi. The bridle trousseau, exhibited on a table, is blesssd by the priest, who takes two rings, dropping them into a glass of wine and consecrates it. The rings are then taken out and placed one on the ring finger of the bride, the other on that of the bridegroom. A portion of the wine being drunk by the bridegroom, he hands the glass to the bride, who tastes it. Sweetmeats wrapped in tinted paper, and a sherbet, known as "Gulab-nabat, are served to the guests.. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The marriage ceremony in a few respects differs from that followed in Western Europe. For instance, before entering the church the pair, standing beneath the bell tower, plight their troth in the hearing of the priest, after which they kneel at the altar with their heads covered with veils. Throughout the service the sponsor holds a silver cross over the pair, and when the service ends the priest gives the bridegroom a belt and a cross, which are worn for three days, and can only be removed after the reading of certain prayers, until which time the marriage is not consummated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As soon as an Armenian expires, the arms are crossed over the chest, and a wax taper being lighted, is placed at the head, while incense is burned in the room. The priest being informed of the death, orders the church bells to be tolled as an intimation to the friends. At the burial the priest, relatives, and friends follow on foot, while the coffin is preceded by persons carrying a cross and torches. The coffin is first of all placed beneath the campanile, and prayers being offered up, it is borne into the church and placed on a catafalque surrounded by tapers, where it remains until the appointed service is read. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the room where the deceased expired a candle is kept constantly burning for forty days, while on the seventh and fortieth days, as well as on the anniversary of the death, a mass is celebrated in the church, and after the last service a feast, to which all relatives and friends are invited, is given, at which a peculiar kind of Pulao with raisins is handed round. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The future of the Armenian race in India is difficult to predict; but if the tendency to adopt English ideas and ways extends, it must overcome the contrary spirit still influencing the majority. In many respects the Jew and Armenian resemble one another. Cut off from the cradle of their religion and nationality they sojourn apart from the European, and exhibit few sympathies for the Hindu or Muhammadan. Each has preserved an ancient established religion which, ordinarily at least, debars the alien and Gentile from admission into its pale, and each is yearning for a spiritual and temporal supremacy in their original home. With such aspirations, however, it has become the habit with Armenians to educate their boys as English parents do, and so successfully has this been followed out, that several have in competition gained admission into the Army and Indian Civil Service. The education and position of the Armenian female, however, leaves much to be desired. | ||

| + | |||

| + | She is generally brought up with only a superficial knowledge of any language; she leads a secluded, uninteresting life, diversified by attendance at church, and by visits to her relatives, and her sympathies are neither cultivated nor encouraged. Until she is raised to an equality with her husband, and acquires those accomplishments which adorn her European sister, it cannot be predicated of the Armenians that the future is for them altogether bright and cheerful. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Armen Sarkissian’s overview== | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/former-armenia-prime-minister-armen-sarkissian-mahatma-gandhi-8351354/?utm_source=newzmate&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=explained&utm_content=6386461&pnespid=ArElrUJZ7zVIlkXEtIrbR0dSoApg2OtyuV9BQrkcNcvK..IO6eo7A5R.Ip.YazWzSknhQdVz Written by Armen Sarkissian, Dec 30, 2022: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Armen Sarkissian writes: The partnership between Armenia and India is not driven by governments alone. It is pushed forward to a great extent by ordinary people from both countries. Governments need to catch-up. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Few nations occupy a more exalted position in our national memory than India — the land where generations of Armenian diaspora communities have thrived and gave shape to the dream of reviving the Armenian state, which had been obliterated over centuries of invasion and rule by foreign powers. Take, for instance, the Mamikonians, a revered aristocratic dynasty which controlled vast swathes of Armenia until the 8th century. A branch of the family moved between Armenia and India, and the greatest warrior it produced — the fifth-century military commander Vartan Mamikonian — bore a Sanskrit name. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Centuries before Vartan Mamikonian led his forces in defence of Christianity against the Persian army, a pair of Indian princes from Magadha had taken refuge in Armenia and even been allowed to raise Hindu settlements. That warmth and liberality were reciprocated by Indian rulers as late as the Mughal era. In 17th-century India, Armenians were highly valued for their artisanship, granted trade privileges, and taken on as advisors by royal courts. So extensive was the network of Armenians in India that by the 19th century, Kolkata — home, among other Armenian-Indians, to the fabled classical singer Gauhar Jaan — had gained a reputation as an Armenian city. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It was in Chennai, however, that ideas of resuscitating the Armenian state first bloomed. As early as 1773, Shahamir Shahamirian, the great Armenian nationalist based in southern India, published his pamphlet on a future Armenian state – a work that has justly come to be regarded as both a roadmap and a draft constitution for a reconstituted Armenia. Two decades after Shahamirian’s book, the first Armenian language journal, Azdarar, was published from Chennai. Together, these two works of print galvanised Armenian communities around the world and sparked a national consciousness. The Armenian republic which existed briefly between 1918 and 1920 was the culmination of an aspiration that had acquired wings in India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Armenian republic which was reborn in 1991 was recognised by India a day after the Soviet Union’s demise. New Delhi chose Yerevan, the Armenian capital, as the site of its first embassy in the Caucasus. My own career as a diplomat and politician, which began in the 1990s, was enhanced by the friendships I forged with Indians —from groundbreaking scientists to pioneering businesspersons and visionary politicians — and influenced by the lessons I learnt from India’s struggle for freedom. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2018, days after being sworn in as the fourth president of Armenia, I was confronted with the most formidable political challenge in Armenia’s post-Soviet history as tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered in the capital to demand the expulsion of the then prime minister. The protest has since been titled the “velvet revolution”, but there was nothing at the time to suggest that it was going to end peacefully. The slightest miscalculation by either side could have resulted in carnage. The Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, which is marked every year on April 24, was around the corner. I feared that we were on the verge of disgracing that solemn occasion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although my role was largely ceremonial, I was adamant that something had to be done. The impetus for what came next emanated from my reading of Mahatma Gandhi, who in my opinion set the highest standard for personal conduct in politics. I told my advisors that I was going to meet the protestors. They baulked at the idea and said plainly that my security detail could not guarantee my safety. But the people massed outside the presidential palace were my compatriots. I could not function as their president if I feared them. So I walked out of the palace and into the crowd and shook hands with the people. Seeing that their first citizen was not some distant figure, they spoke freely. This breakthrough was worth every risk to my life. Suddenly, there were cheers. And instead of a bloodbath, Armenia experienced a peaceful transfer of power in the weeks that followed. This is a story I remember fondly because it speaks to the enduring power of nonviolence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are, however, still occasions when force is unavoidable, especially when it comes to nationhood and sovereignty. Over the past half-decade, India has emerged as Armenia’s pre-eminent defence partner. The current leadership of India is unafraid to speak bluntly about the ongoing aggression in the Caucasus, including the blockade of the Lachin corridor that has cut-off 1,20,000 Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh from the world. As Armenia’s president, I cherished my excellent relations with India and it is heartening to see Delhi’s solidarity with Armenia in this time of crisis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|AARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|K ARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Armenian communities in India= | ||

| + | (From ''People of India/ National Series Volume VIII.'' Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, [http://www.facebook.com/Indpaedia Indpaedia.com]. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Synonyms: Hay [West Bengal] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Surnames: Arathun, Basil, Grigory, Poladian, Sukias [West Bengal] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|AARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|K ARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|AARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|K ARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Armenians in India, city-wise= | ||

| + | ==Chennai== | ||

| + | '''A SLICE OF ARMENIA''' | ||

[http://epaper.timesofindia.com/Default/Scripting/ArticleWin.asp?From=Archive&Source=Page&Skin=TOINEW&BaseHref=TOICH/2012/01/28&PageLabel=46&EntityId=Ar04601&ViewMode=HTML ''The Times of India''] | [http://epaper.timesofindia.com/Default/Scripting/ArticleWin.asp?From=Archive&Source=Page&Skin=TOINEW&BaseHref=TOICH/2012/01/28&PageLabel=46&EntityId=Ar04601&ViewMode=HTML ''The Times of India''] | ||

[[File: Armenian Church.jpg| Armenian Church, Chennai |frame|500px]] | [[File: Armenian Church.jpg| Armenian Church, Chennai |frame|500px]] | ||

| − | + | ||

Dr S Suresh walks down the hallowed corridors of the Armenian Church and gives us a glimpse of its history and architecture… | Dr S Suresh walks down the hallowed corridors of the Armenian Church and gives us a glimpse of its history and architecture… | ||

| Line 28: | Line 166: | ||

The writer is the Tamil Nadu State Convener INTACH | The writer is the Tamil Nadu State Convener INTACH | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Kolkata== | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Armenia-still-lives-in-the-heart-of-Kolkata-24042016008058 ''The Times of India''], Apr 24 2016 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ajanta Chakraborty | ||

| + | |||

| + | | ||

| + | '''Armenia still lives in the heart of Kolkata''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | City's 195-year-old Armenian school had a near-death experience when its student body shrank to one. But it has now returned to life, thanks to immigrant students | ||

| + | |||

| + | What Parsis were to Mumbai, Armenians were to Kolkata -a refugee race that washed up on Indian shores before the British, and proceeded to establish iconic businesses and institutions that live to this day.One such in Kolkata is the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy (ACPA), nearly two centuries old. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Built in 1821 as a residential school for children of Armenian descent, ACPA was founded by two Armenian merchants, Astvatsatur Muradkhanian and Manatsakan Vardanian who hailed from Julfa (now in Iran). The school was founded to impart an `Armenian' education to its students, in their language, and about their culture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the early 19th century, the Armenians were a prominent business community in Kolkata that ran coal mines, indigo and shellac businesses, and built some of the city's famous landmarks, including Stephen Court on Park Street and Grand Hotel (today Oberoi Grand). | ||

| + | |||

| + | But after the British quit India, so did most of the Armenians, who migrated abroad. Half a century ago, Kolkata's Armenian population dwindled to just 2,000, vanishing still further to leave behind only around 150. Two of these Indo-Armenians are counted among the 68 students currently studying at the school; the rest are immigrant Armenians from Iraq, Iran, Russia and Armenia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The school -in whose original building novelist William Makepeace Thackeray was born -has had its ups and downs. Its student body shrank and expanded -going from 138 in 1932, to 149 in 2003, and even plummeting to a solitary student in 1990, perhaps marking the most trying year in the school's long history. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In February 1999, a Calcutta high court ruling transferred the school's administra tion to Armenia's Mother See of Holy Etch miadzin, the administrative headquarters of the Armenian Apostolic Church. It is now the Pope of Armenia who appoints the school manager. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Since the institution's guardianship was vested with the church, the school has maintained its standards and a minimum number of students,“ said Rev. Zaven Ya zichyan, manager of Armenian College and pastor of the Indian-Armenian Spir itual Pastorate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following the transfer of power, the first batch of 34 immigrant students reached Kolkata from Iraq, Iran, Russia and Arme nia -sent here for the free education and boarding provided by the school. Often, Armenian families in places like Iraq and Iran send their children here even as they plan to migrate to the West, the school be coming an interim harbour for their chil dren. ACPA now routinely invites the dias pora abroad to enroll their children here. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the run-up to their 200th year celebra tions in 2021, Rev. Yazichyan has been at tempting to revive the institution. Among the ambitious projects is the preservation and digitization of the Araratian library, set up in 1828 and named after Mount Ara rat, the place where Noah's Ark landed after the Flood. Other efforts include the creation of a databank of all Armenians from Kol kata (the last was created in 1956) and for mal associations with other international educational organizations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To retain a cultural identity , ACPA teach es Armenian history , language and religion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On visiting the campus on Free School Street (some say it got its name from the free Armenian school), the students seem content. Hovhannes Saringulyar, who teach es Armenian history, says, “If they miss their parents, they talk to them on Skype.“ | ||

| + | ==Surat== | ||

| + | ===A decline, 1980-1800=== | ||

| + | [http://www.sunday-guardian.com/news/shunned-by-brits-indians-descendant-will-rule-uk ''The Guardian''], 15th Jun 2013 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Seth, the Armenian historian, writes: “The decline and dispersion of the Armenians at Surat must have been very rapid.… During the last two decades of the 18th century (1780-1800), there were 33 (Armenian) merchants besides many others in the humbler walks of life.… Their numbers dwindled down to only (seven) souls in 1820. Their names were: Mrs Elizabeth Farbessian, Mrs Maishkhanoom Avietian, Mrs Mariam Vardanian, Stephen Petrus, Minas Margarian, Gregore Agahian and Arrathoon Balthazarian, the only well-to-do amongst them being the lady mentioned first.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''The warehouse''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Jahnubhai Patel, who runs a zari business in the area, does not remember any Armenians but says his ancestors bought the home-cum-warehouse he owns from a Parsi businessman. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “There were many Parsis here then. The English Factory (a former East India Company warehouse-cum-house where Forbes once worked and lived) down the road was also owned by a Parsi businessman called Cooper who bought it from the British,” Patel said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We know this because his last descendant, who lived in the massive building all alone in the 1960s, was insane and broke down the place using a bulldozer as he was tired of researchers from India and abroad coming to his place regularly and requesting a tour of the premises,” recounts Patel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meghani confirmed the building’s razing by its “insane” owner. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “Prince William better come and collect the remaining bricks on this half-wall of the English Factory before the children of the adjoining I.P. Mission school take them away to use them as wickets in cricket matches on the school compound,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Called Saudagarwada even today, the area’s architectural character has largely changed, but demographically it still remains a predominantly merchant colony like it was when Forbes landed on the banks of the Tapi in 1809. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “As a young officer of the East India Company, he would have sailed in a boat down the Tapi from Suvalli, a British jetty near Surat, and landed on the riverbanks in the old city,” Mahida said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The warehouse of the East India Company, where Forbes would have worked while in Surat, is a few furlongs from the Tapi’s banks. Today, destitute people and immigrant workers catch their afternoon nap on the river embankment by the English Factory, as the warehouse was called. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When The Telegraph visited the place, only a 12ft by 20ft, moss-laden, rundown wall of the “factory” stood. The remnants were in effect no more than a temporary boundary wall for an under-construction residential high-rise coming up where the warehouse once stood. Nothing else of it remains. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Forbes’s time, the “factory” or warehouse was a two-storey structure of bricks and timber, said Meghani, quoting from a research paper on East India Company factories and facilities in Surat by Kyoto University’s Haneda Masashi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Masashi based his research on old Surat Municipal Corporation records before most of them were destroyed in a flood in 2006,” Meghani said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While the ground floor was used as a godown, Forbes would have lived in the comfortable staff quarters on the first floor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | About 500 yards down the same street would have stood the warehouses of other European merchant companies, owned by the Portuguese, Dutch and the French. The Armenian settlement where Eliza would have lived began after that and the Armenian church would have been down the same street. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The entire area would have had a radius of one kilometre. It would have been bordered by gardens, fountains and a red-light district from the Mughal era that existed in the old city till about a decade ago. Saudagarwada would have been a bustling place,” Meghani said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Indian-Armenian marriages=== | ||

| + | [http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130621/jsp/frontpage/story_17032045.jsp#.VwoMpDH2sfY ''The Telegraph''], June 21, 2013 | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: According to Armenian tradition, a girl’s last name was a derivative of either her father’s name or husband’s name.jpg| According to Armenian tradition, a girl’s last name was a derivative of either her father’s name or husband’s name ; Picture courtesy: [http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130621/jsp/frontpage/story_17032045.jsp#.VwoMpDH2sfY ''The Telegraph''], June 21, 2013|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Meghani said that marriages between Armenian men and Indian women were uncommon but not unheard-of around the end of the 18th century. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The community had been settled in India for over 500 years by then and was seen as close to the Mughal throne and hence powerful. So, intermarriages would not have been terribly frowned upon,” Meghani said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''The romance''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | In such a “happening” place, buzzing with pretty local girls and dashing merchants and sailors, the romance of Forbes and Eliza would have blossomed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “And for what it is worth, the relationship seems to have been more than a bond of convenience,” Meghani suggested. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the accepted norm of keeping mistresses, did the 23-year-old Forbes love a 19-year-old Eliza enough to make her his wife? “It seems he tried,” Meghani said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “If British researchers say he may have married her in the Armenian church, it would have been a very honourable thing to do given that if he had not, no one would have raised a finger,” Meghani said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the records, Forbes, when posted to Yemen soon after, took Eliza, pregnant with his daughter, along. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “When the child was delivered in Yemen, he named her Kitty after his mother. By the time Eliza and Forbes returned to Surat, they had had another baby, Alexander. Later, she delivered another son, Fraser, who died after six months,” Meghani said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Although Forbes neglected the family after moving to Bombay, he did send a close friend, Thomas Fraser, another Scotsman, to look up Eliza in Surat. It was on Fraser’s suggestion that he sent Kitty to Scotland. He even mentioned his children and Eliza in his will. Does not seem like a scoundrel to me,” said Meghani. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===No Armenian population in Surat: 2013=== | ||

| + | [http://www.telegraphindia.com/1130621/jsp/frontpage/story_17032045.jsp#.VwoMpDH2sfY ''The Telegraph''], June 21, 2013 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Samyabrata Ray Goswami | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''On the elusive trail of Eliza Kewark''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prince William need not come knocking to Surat; his folks do not live here any more. The genetic needle that threaded his DNA to an Indian ancestor is more or less lost in the haystack of history. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But if he takes a stroll around the old city, perhaps among the oldest cosmopolitan pre-British urban centres in India, he might pick up a few old threads to spin a yarn about his multi-cultural genealogy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are no Armenians in Surat any more. Residents of the old city, largely small-scale textile traders, have long bought over their properties and razed them to build newer houses and trading markets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But it is in the alleys of old Surat’s Saudagarwada (borough of merchants) that his mother’s Indian-Armenian ancestor, Eliza Kewark, lived a lonely life after her Scottish husband deserted her and died aboard a ship on his way back home to Aberdeenshire. | ||

| + | |||

| + | William’s mother Diana was a direct descendant of Kitty, daughter of Eliza and Scotsman Theodore Forbes. | ||

| + | =See also= | ||

| + | [[Armenians in India]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Armenians in India, 1895]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Eliza Kewark]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|A | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|K | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|AARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|K ARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Communities|AARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A ARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|K ARMENIANS IN INDIAARMENIANS IN INDIA | ||

| + | ARMENIANS IN INDIA]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:43, 25 December 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] As of 1895

This section is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

[edit] Armenians

IN 1605 Shah 'Abbas invaded Armenia, and transferred 12,000 inhabitants of Julfa, on tbe Araxes, to the neighbourhood of Ispahan, where he allotted them land on the banks of the Zindarud, which subsequenty became the site of a town, since known as New Julfa. While Shah 'Abbas lived, he treated the settlers with remarkable liberality, advancing money without exacting interest, granting the free exercise of their religion, and permitting them to elect a "Kalan-tar." or headman, of their own. No Muhammadan was allowed to reside within the walls, and, as the murder of an Armenian could only be expiated by the rigorous law of retaliation, the inhabitants were respected, and favoured, by the Persians themselves. During the reign of Shah Hussain (1694-1722), however, many of these privileges were repealed, and the slayer of an Armenian was absolved from all punishment on payment of a load of corn. The prosperity of the settlement was destroyed by Shah Mahmud and the Afghans in 1722, but not until after a gallant though unavailing resistance.1

stone of one Khwajah Martinas, who died in 1611.1 It was, however, into Western India that Armenians chiefly congregated. In 1623 Pietro della Valle found the Dutch intermarrying with them; and in 1638 Mandelslo encountered Armenians in Surat and Gujarat. Tavernier,2 moreover, has preserved the name of one Corgia, brought up by Shah Jahan, an excellent wit and poet, much in the King's favour, who had conferred on him many fair commands, though he could never by threats or promises win him to turn Muhammadan. Bender, too, mentions Armenians in Delhi, who were ruining the inland trade of the Dutch by their competition.

If Mr. Glanius is to be relied on, a body of Armenian cavalry, celebrated for its horses and discipline, accompanied the army of Mir Jamlah, in 1662, when he invaded Assam.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century many Armenians resided at Chinsurah, and they possessed "a pretty good garden" opposite Calcutta.. During the latter days of Muhammadan rule the principal Armenian settlement in Bengal was at Saidabad, near Murshidabad, whence were annually exported valuable assortments of piece goods and raw silk.

The Armenians have always been distinguished as enterprising traders throughout Asia, and as early as 1690, when the East India Company was entering upon its marvellous career, Mr. Charnock received3 instructions to employ them to sell the annual shipments in the interior, and buy fine muslins and other valuable goods. The ostensible reason for this preference being that they could transact business with the native traders better than agents of the Company provided with a firman.3 In 1694, again, a proposal was made to the Armenians of Ispahan to sell the goods of the Company, or barter them for silk, money, and "Caramania wool;" but this project failed, as the Armenians themselves imported, by Aleppo, the goods of the Turkey Company. During the eighteenth century, the Armenian community in Bengal prospered, and, favoured by many special grants from the Imperial court, secured much of the inland trade of the province. Several individuals raised themselves to positions of eminence during the civil wars preceding the overthrow of the Mughal power. Coja (Khwajah) Gregory, better known as Gurghin Khan, commanded the artillery of Mir Qasim at the battle of Gheriah, in August, 1763; while his brother, Coja Petrus, or Petrus Arrathoon, was still more intimately connected with the early struggles of the Company, being as Gumastha, or agent, of both Sirajuddaulah, and Mir Qasim, mixed up with many of the intrigues of that eventful period. The latter survived till 1782, when he died, leaving great wealth. At this time the Armenians were often charged, but probably without sufficient reason, with being turbulent and crafty, and doing much injury by thwarting the policy of the English Company. In spite of this accusation, however, they were permitted to reside in Calcutta in 1758; but an order forbidding their dwelling in the smaller factories was in force as late as 1765. The Court of Directors, regarding this busy people as the pioneers of commerce, issued an order that whenever a certain number congregated together, an Armenian church should be built for them.

The history of the Armenian colony at Dacca has not been preserved. It is stated, on doubtful authority, that when Job Charnock returned to Calcutta in 1698, he invited the Armenian merchants in Dacca to settle in the new town; but the first authentic record is a time-worn tombstone in the old churchyard of Tezgaon, which marks the grave of one Avitis, an Armenian trader, who died on the 5th August, 1714. At the middle of the eighteenth century Armenians, as well as Europeans, were extensively engaged in the slave trade, and if we judge of the morality of the time by that described by one of their number, the standard was not a high one. In 1747 a rich Armenian died at Dacca without heirs, and to prevent the estate lapsing to the Nawab, the narrator consented to come forward as a son of the deceased. The perjury is justified on the plea that it prevented "wild beasts from eating the flesh of lambs."1

According to the census of 1866 there were 703 Armenians resident in Calcutta, while on the 6th April, 1876, they numbered 707. In 1872, again, the Armenian population of Bengal proper was only 875, and of that number 710 resided in and around Calcutta, and 113 in Dacca. Mr. I. G. Pogose, in 1870, estimated the Dacca Armenians at 107, of whom 36 were males, 23 females, and 48 children. The professions and occupations of the males were as follows: one was a priest, five landholders, three merchants, one a barrister, five shopkeepers, seven shopmen, and four Government servants. Until comparatively recent times no Armenian could hold land; but under the Muhammadan rule many were farmers of the revenue and executive officers.

The causes which have checked the growth of the Armenians in Eastern India have been recapitulated by a writer in the Calcutta Review,2 who points out that the early settlers were robust, energetic, and frugal men, devoting their whole time and thoughts to trade, while their descendants, lacking many of the peculiar traits of the race, have sadly degenerated. Separation from home influences, and association with alien races, effected a marked change of habits, and, resisting the introduction of European customs, they insensibly adopted many Indian ones. The indolence, moreover, induced by a hot, uncongenial climate, along with a rooted aversion to physical exertion, promoted habits of immorality and intemperance. Early marriages became fashionable, the offspring growing up sickly and tainted by disease. In-breeding still further impaired the race, and only those families who sought or brides in distant cities, or among immigrants from Persia, have inherited the muscular healthy constitutions of the parent stock. As late as a generation ago the Armenians of India were generally illiterate, being totally ignorant of European literature. They spoke and often read Armenian, they conversed fluently in Persian, Urdu, and Bengali; but they were unacquainted with the English language. Of late years, however, although Armenian is till the language of their homes, English is spoken universally, and an English education is considered indispensable. The English costume, too, is always worn, and the national dress is only seen on festive occasions.

The modern Armenian is proverbially hospitable, while his open-handed charity to the poor of all creeds, his benevolence, and sympathy for the destitute and unfortunate of his own faith, and his kindness to his native servants and acquaintances, excite the admiration of his fellow townsmen.

The Catholicos, or Patriarch, of the Armenian church resides at Echmadzin, in Russian Armenia. Not only is he the Primat, but his monastery is the centre where pilgrims join in fraternal union with their brethren of other lands, and from which the Chrism, or holy oil, is brought for the services of the church in the East. The Bishop of Julfa has jurisdiction over all the Armenian churches in India, and by him the priests are inducted, or translated. India has so few attractions for the priesthood, that livings in that country, it is said, can only be got by an offering of twenty Tomans, equivalent to ten guineas. The priests met with in India are always married men, whose wives and families remain at Julfa, as hostages for their return. Five years is the fixed period of their residence, but on application a transfer to another church is often obtained. The greatest objection to this system is, that new arrivals can only converse in Persian and Armenian, while their flock speak Armenian, rarely Persian. Having acquired the vernacular, they are transferred to Singapore, or China, where another language has to be learned, under the same discouraging circumstances.

The position of an Armenian priest in India is an unenviable one. Separated from all his dearest ties, he finds himself in a small community stirred by the influences of strange races, and rival faiths, and dependent on the goodwill and liberality of his brethren. Services, beginning before daybreak, and lasting for six or seven hours, at which the congregation only attend towards the end; fasts twice every week, and during Lent continuing for weeks, tell upon the strongest constitutions. But the interest shown in the spiritual welfare of his flock, the sympathy shown to the sick and dying, and their moral, and generally blameless, lives, are the bonds which bind and endear them to their people.

The four great festivals of the Armenian church are the Nativity, Ascension, Annunciation, and that observed in honour of St. George. These festivals, as in the Greek church, are kept according to the old style; for instance, the Nativity, along with the Epiphany, on the 6th January. The Assumption, however, celebrated by the Greek and Latin churches on the 15th Ausgust, is commemmorated by the Armenian on the Sunday between the 12th and 18th of that month.

The dogmas, rites, and practices of the Armenian church in India1 are identical with those of the parent establishment, being uninfluenced by contact with other Christian churches, but several customs are followed which are not mentioned by writers on such matters. Thus, on the Assumption, raisins wrapped in coloured paper are distributed in the church; and until late years a large pile of dry grass was collected near the church door on Ash Wednesday, and at a certain part of the service the congregation, carrying lighted tapers, defiled out of the building, and set fire to it.

At Easter and Christmas, after service, the priest visits each household, presenting the goodman with a cake of unleavened bread, in return for which he receives a fee, and his attendants wine, sweetmeats, and dyed eggs. Although they disbelieve in the purgatory of the Roman Church, Armenians admit that the spirits of the dead remain till the Day of Judgment in Paradise, or a place of probation. During Christmas and Holy Week, therefore, incense and wax tapers are forwarded to the priest who performs a service at the grave of the deceased relatives. Armenians are forbidden, like the Jews and Muham-

1 For interesting particulars regarding this Christian Sect, see "Histoire, Dogmes, Traditions et Liturgie de l'Eglise Armenienne Orientale." Par E. Dulaurier, Paris, 1855.

madans, to eat blood or things strangled, and on Christmas and Easter the flesh eaten must have been killed by a Christian, and a godfather.

The public declaration of vows is one of the most solemn ceremonies of the Armenians. The person vowing presents the priest with two wax candles and two rupees for each pledge. Two gilt hands with the forefingers and thumbs united, the other fingers extended and adorned with jewels, being taken from the altar are dipped into holy water, and the lips of all present touched, whils the witness kneeling rests his forehead on the floor. The priest, after repeating certain prayers, holds the two hands over the people and blesses them.

Armenians esteem the "Little Gospel" as only second in value to the Bible itself, and are fond of detailing incidents recorded in it. This uncanonical scripture is the "Historia de Nativitate Mariae et de Infantia Salvatoris."1

Last century the Armenians observed many Persian, Bengali, and European customs. The dress of the men consisted of a Persian vest, or Jamah, fastened with a belt (Patka), and loose trousers. Their head-dress was a black brimless hat, about eight inches high. The costume of the women resembled that of the men, but the vests were longer. They wore the hair hanging down loose behind, adorned with strings of pearls, and other gems, and covered with a hat, called Kambhara. Moreover, their teeth were stained with Misi, the hands and feet with Menhdi. It was considered indecorous and improper for the women to speak to, or appear before men in public, and, like the Muhammadan wife, the Armenian had to endure great hardships when most requiring sympathy, the doors and windows of her room were carefully closed against evil spirits for forty days, a fire was kept burning on the threshold, and no one dared to enter the room till mustard seed had been cast on the embers. As a further protection the child was arrayed with strings of amulets and charms.

The amusements of the men were confined to kite-flying, in which pastime much money was lost and won, and to the fighting of rams and game cocks. Native music was, and still is, preferred to European, and dinner parties wound up with "Nach" dancing and singing. At meals tables were not used, but mats and carpets being spread, the guests squatted and ate with their fingers. The Armenian cuisine more nearly resembles that of the Muhammadans than the English, and at feasts the variety of dishes is so embarrassing that the etiquette requiring each guest to taste of every dish becomes positively dangerous.

1 Giles' "Uncanonical Gospels." London, 1852.

1 "The Life and Adventures of Joseph Emin, and Armenian." London, 1792.

2 "The Armenian in London Physically considered," vol. xxx, June, 1858.

1 "J.A.S." of Bengal, August, 1874.

2 "Voyage," Liv. i, c. 7.

3 "Annals of the E.I. Company," iii, 88, 160.

Armenian marriages are ordinarily negotiated by the parents, or guardians. A few days before the wedding the hands and feet of the bride are stained with Menhdi. The bridle trousseau, exhibited on a table, is blesssd by the priest, who takes two rings, dropping them into a glass of wine and consecrates it. The rings are then taken out and placed one on the ring finger of the bride, the other on that of the bridegroom. A portion of the wine being drunk by the bridegroom, he hands the glass to the bride, who tastes it. Sweetmeats wrapped in tinted paper, and a sherbet, known as "Gulab-nabat, are served to the guests..

The marriage ceremony in a few respects differs from that followed in Western Europe. For instance, before entering the church the pair, standing beneath the bell tower, plight their troth in the hearing of the priest, after which they kneel at the altar with their heads covered with veils. Throughout the service the sponsor holds a silver cross over the pair, and when the service ends the priest gives the bridegroom a belt and a cross, which are worn for three days, and can only be removed after the reading of certain prayers, until which time the marriage is not consummated.

As soon as an Armenian expires, the arms are crossed over the chest, and a wax taper being lighted, is placed at the head, while incense is burned in the room. The priest being informed of the death, orders the church bells to be tolled as an intimation to the friends. At the burial the priest, relatives, and friends follow on foot, while the coffin is preceded by persons carrying a cross and torches. The coffin is first of all placed beneath the campanile, and prayers being offered up, it is borne into the church and placed on a catafalque surrounded by tapers, where it remains until the appointed service is read.

In the room where the deceased expired a candle is kept constantly burning for forty days, while on the seventh and fortieth days, as well as on the anniversary of the death, a mass is celebrated in the church, and after the last service a feast, to which all relatives and friends are invited, is given, at which a peculiar kind of Pulao with raisins is handed round.

The future of the Armenian race in India is difficult to predict; but if the tendency to adopt English ideas and ways extends, it must overcome the contrary spirit still influencing the majority. In many respects the Jew and Armenian resemble one another. Cut off from the cradle of their religion and nationality they sojourn apart from the European, and exhibit few sympathies for the Hindu or Muhammadan. Each has preserved an ancient established religion which, ordinarily at least, debars the alien and Gentile from admission into its pale, and each is yearning for a spiritual and temporal supremacy in their original home. With such aspirations, however, it has become the habit with Armenians to educate their boys as English parents do, and so successfully has this been followed out, that several have in competition gained admission into the Army and Indian Civil Service. The education and position of the Armenian female, however, leaves much to be desired.

She is generally brought up with only a superficial knowledge of any language; she leads a secluded, uninteresting life, diversified by attendance at church, and by visits to her relatives, and her sympathies are neither cultivated nor encouraged. Until she is raised to an equality with her husband, and acquires those accomplishments which adorn her European sister, it cannot be predicated of the Armenians that the future is for them altogether bright and cheerful.

[edit] Armen Sarkissian’s overview

Written by Armen Sarkissian, Dec 30, 2022: The Indian Express

Armen Sarkissian writes: The partnership between Armenia and India is not driven by governments alone. It is pushed forward to a great extent by ordinary people from both countries. Governments need to catch-up.

Few nations occupy a more exalted position in our national memory than India — the land where generations of Armenian diaspora communities have thrived and gave shape to the dream of reviving the Armenian state, which had been obliterated over centuries of invasion and rule by foreign powers. Take, for instance, the Mamikonians, a revered aristocratic dynasty which controlled vast swathes of Armenia until the 8th century. A branch of the family moved between Armenia and India, and the greatest warrior it produced — the fifth-century military commander Vartan Mamikonian — bore a Sanskrit name.

Centuries before Vartan Mamikonian led his forces in defence of Christianity against the Persian army, a pair of Indian princes from Magadha had taken refuge in Armenia and even been allowed to raise Hindu settlements. That warmth and liberality were reciprocated by Indian rulers as late as the Mughal era. In 17th-century India, Armenians were highly valued for their artisanship, granted trade privileges, and taken on as advisors by royal courts. So extensive was the network of Armenians in India that by the 19th century, Kolkata — home, among other Armenian-Indians, to the fabled classical singer Gauhar Jaan — had gained a reputation as an Armenian city.

It was in Chennai, however, that ideas of resuscitating the Armenian state first bloomed. As early as 1773, Shahamir Shahamirian, the great Armenian nationalist based in southern India, published his pamphlet on a future Armenian state – a work that has justly come to be regarded as both a roadmap and a draft constitution for a reconstituted Armenia. Two decades after Shahamirian’s book, the first Armenian language journal, Azdarar, was published from Chennai. Together, these two works of print galvanised Armenian communities around the world and sparked a national consciousness. The Armenian republic which existed briefly between 1918 and 1920 was the culmination of an aspiration that had acquired wings in India.

The Armenian republic which was reborn in 1991 was recognised by India a day after the Soviet Union’s demise. New Delhi chose Yerevan, the Armenian capital, as the site of its first embassy in the Caucasus. My own career as a diplomat and politician, which began in the 1990s, was enhanced by the friendships I forged with Indians —from groundbreaking scientists to pioneering businesspersons and visionary politicians — and influenced by the lessons I learnt from India’s struggle for freedom.

In 2018, days after being sworn in as the fourth president of Armenia, I was confronted with the most formidable political challenge in Armenia’s post-Soviet history as tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered in the capital to demand the expulsion of the then prime minister. The protest has since been titled the “velvet revolution”, but there was nothing at the time to suggest that it was going to end peacefully. The slightest miscalculation by either side could have resulted in carnage. The Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, which is marked every year on April 24, was around the corner. I feared that we were on the verge of disgracing that solemn occasion.

Although my role was largely ceremonial, I was adamant that something had to be done. The impetus for what came next emanated from my reading of Mahatma Gandhi, who in my opinion set the highest standard for personal conduct in politics. I told my advisors that I was going to meet the protestors. They baulked at the idea and said plainly that my security detail could not guarantee my safety. But the people massed outside the presidential palace were my compatriots. I could not function as their president if I feared them. So I walked out of the palace and into the crowd and shook hands with the people. Seeing that their first citizen was not some distant figure, they spoke freely. This breakthrough was worth every risk to my life. Suddenly, there were cheers. And instead of a bloodbath, Armenia experienced a peaceful transfer of power in the weeks that followed. This is a story I remember fondly because it speaks to the enduring power of nonviolence.

There are, however, still occasions when force is unavoidable, especially when it comes to nationhood and sovereignty. Over the past half-decade, India has emerged as Armenia’s pre-eminent defence partner. The current leadership of India is unafraid to speak bluntly about the ongoing aggression in the Caucasus, including the blockade of the Lachin corridor that has cut-off 1,20,000 Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh from the world. As Armenia’s president, I cherished my excellent relations with India and it is heartening to see Delhi’s solidarity with Armenia in this time of crisis.

[edit] Armenian communities in India

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Hay [West Bengal]

Surnames: Arathun, Basil, Grigory, Poladian, Sukias [West Bengal]

[edit] Armenians in India, city-wise

[edit] Chennai

A SLICE OF ARMENIA The Times of India

Dr S Suresh walks down the hallowed corridors of the Armenian Church and gives us a glimpse of its history and architecture…

Chennai has the rare distinction of being one of the few Asian cities that had a sizeable population of Jews and Armenians a few centuries ago. Indeed, the Armenians and the Jews were among the earliest foreign traders to settle in this city. They mostly lived in and around George Town. The Armenians were known for their wisdom and sincerity. Many of them worked, along with the British, in the various government offices in the city. The British were so impressed by the efficiency of the Armenians that they gifted large tracts of land to the community and even built a timber church for them near Fort St George.

The Armenians designed and built a few buildings for use by the British population of this city. One of the largest and most important amongst these buildings is the Clive House, also known as Admiralty House, built within Fort St George in the early eighteenth century by an affluent Armenian merchant named Nazar Jacob Jan. Presently, the Armenian church in George Town is, however, the sole visible testimony of the presence of the Armenians in this city.

The Armenian church, also known as the Armenian Church of Virgin Mary, is located on Armenian Street, not too far from the NSC Bose Road and the Law College and the High Court. The church was built in 1772 but according to some locals, it was originally built in 1712 and expanded and rebuilt in 1772 on the site of the old Armenian cemetery. The church was the result of the efforts of Aga Shawmier Sultan, a prominent Armenian trader. He gifted his ancestral land for the erection of this church.

Unlike many other churches and other religious buildings in George Town and other parts of Chennai, the Armenian Church is built within a spacious courtyard enclosed by high walls. From the street, the courtyard is accessed through tall black wooden doors set within a large entrance on a platform. The secluded courtyard has several gravestones and a lovely garden and thus provides a striking contrast to the din and noise of the crowded streets in the neighbourhood. The church is mainly built of bricks and is plastered with lime. The exterior walls are profusely ornamented. The imposing bell tower is located to the south of the main church building. The bell tower houses some of the largest bells of the city. Art historians have described the church as a specimen of the famous Baroque style of architecture that was very popular in Europe, mainly Italy, in the seventeenth century.

In recent decades, there has been a marked decrease in the population of the Armenians in Chennai. Presently, only a few families belonging to this community reside in the city. Hence, the church is not extensively used. Sometimes, it is used by members of other Christian sects. Thus, the church is now more a heritage building than a religious monument. Although closely linked to the early history of the British rule in India and presently well-preserved by the owners, the church, unfortunately, does not attract many tourists.

The writer is the Tamil Nadu State Convener INTACH

[edit] Kolkata

The Times of India, Apr 24 2016

Ajanta Chakraborty

Armenia still lives in the heart of Kolkata

City's 195-year-old Armenian school had a near-death experience when its student body shrank to one. But it has now returned to life, thanks to immigrant students

What Parsis were to Mumbai, Armenians were to Kolkata -a refugee race that washed up on Indian shores before the British, and proceeded to establish iconic businesses and institutions that live to this day.One such in Kolkata is the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy (ACPA), nearly two centuries old.

Built in 1821 as a residential school for children of Armenian descent, ACPA was founded by two Armenian merchants, Astvatsatur Muradkhanian and Manatsakan Vardanian who hailed from Julfa (now in Iran). The school was founded to impart an `Armenian' education to its students, in their language, and about their culture.

In the early 19th century, the Armenians were a prominent business community in Kolkata that ran coal mines, indigo and shellac businesses, and built some of the city's famous landmarks, including Stephen Court on Park Street and Grand Hotel (today Oberoi Grand).

But after the British quit India, so did most of the Armenians, who migrated abroad. Half a century ago, Kolkata's Armenian population dwindled to just 2,000, vanishing still further to leave behind only around 150. Two of these Indo-Armenians are counted among the 68 students currently studying at the school; the rest are immigrant Armenians from Iraq, Iran, Russia and Armenia.

The school -in whose original building novelist William Makepeace Thackeray was born -has had its ups and downs. Its student body shrank and expanded -going from 138 in 1932, to 149 in 2003, and even plummeting to a solitary student in 1990, perhaps marking the most trying year in the school's long history.

In February 1999, a Calcutta high court ruling transferred the school's administra tion to Armenia's Mother See of Holy Etch miadzin, the administrative headquarters of the Armenian Apostolic Church. It is now the Pope of Armenia who appoints the school manager.

“Since the institution's guardianship was vested with the church, the school has maintained its standards and a minimum number of students,“ said Rev. Zaven Ya zichyan, manager of Armenian College and pastor of the Indian-Armenian Spir itual Pastorate.

Following the transfer of power, the first batch of 34 immigrant students reached Kolkata from Iraq, Iran, Russia and Arme nia -sent here for the free education and boarding provided by the school. Often, Armenian families in places like Iraq and Iran send their children here even as they plan to migrate to the West, the school be coming an interim harbour for their chil dren. ACPA now routinely invites the dias pora abroad to enroll their children here.

In the run-up to their 200th year celebra tions in 2021, Rev. Yazichyan has been at tempting to revive the institution. Among the ambitious projects is the preservation and digitization of the Araratian library, set up in 1828 and named after Mount Ara rat, the place where Noah's Ark landed after the Flood. Other efforts include the creation of a databank of all Armenians from Kol kata (the last was created in 1956) and for mal associations with other international educational organizations.

To retain a cultural identity , ACPA teach es Armenian history , language and religion.

On visiting the campus on Free School Street (some say it got its name from the free Armenian school), the students seem content. Hovhannes Saringulyar, who teach es Armenian history, says, “If they miss their parents, they talk to them on Skype.“

[edit] Surat

[edit] A decline, 1980-1800

The Guardian, 15th Jun 2013

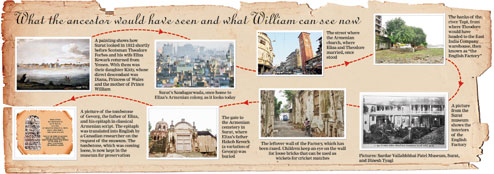

Seth, the Armenian historian, writes: “The decline and dispersion of the Armenians at Surat must have been very rapid.… During the last two decades of the 18th century (1780-1800), there were 33 (Armenian) merchants besides many others in the humbler walks of life.… Their numbers dwindled down to only (seven) souls in 1820. Their names were: Mrs Elizabeth Farbessian, Mrs Maishkhanoom Avietian, Mrs Mariam Vardanian, Stephen Petrus, Minas Margarian, Gregore Agahian and Arrathoon Balthazarian, the only well-to-do amongst them being the lady mentioned first.”

The warehouse

Jahnubhai Patel, who runs a zari business in the area, does not remember any Armenians but says his ancestors bought the home-cum-warehouse he owns from a Parsi businessman.

“There were many Parsis here then. The English Factory (a former East India Company warehouse-cum-house where Forbes once worked and lived) down the road was also owned by a Parsi businessman called Cooper who bought it from the British,” Patel said.

“We know this because his last descendant, who lived in the massive building all alone in the 1960s, was insane and broke down the place using a bulldozer as he was tired of researchers from India and abroad coming to his place regularly and requesting a tour of the premises,” recounts Patel.

Meghani confirmed the building’s razing by its “insane” owner.

“Prince William better come and collect the remaining bricks on this half-wall of the English Factory before the children of the adjoining I.P. Mission school take them away to use them as wickets in cricket matches on the school compound,” he said.

Called Saudagarwada even today, the area’s architectural character has largely changed, but demographically it still remains a predominantly merchant colony like it was when Forbes landed on the banks of the Tapi in 1809.

“As a young officer of the East India Company, he would have sailed in a boat down the Tapi from Suvalli, a British jetty near Surat, and landed on the riverbanks in the old city,” Mahida said.

The warehouse of the East India Company, where Forbes would have worked while in Surat, is a few furlongs from the Tapi’s banks. Today, destitute people and immigrant workers catch their afternoon nap on the river embankment by the English Factory, as the warehouse was called.

When The Telegraph visited the place, only a 12ft by 20ft, moss-laden, rundown wall of the “factory” stood. The remnants were in effect no more than a temporary boundary wall for an under-construction residential high-rise coming up where the warehouse once stood. Nothing else of it remains.

In Forbes’s time, the “factory” or warehouse was a two-storey structure of bricks and timber, said Meghani, quoting from a research paper on East India Company factories and facilities in Surat by Kyoto University’s Haneda Masashi.

“Masashi based his research on old Surat Municipal Corporation records before most of them were destroyed in a flood in 2006,” Meghani said.

While the ground floor was used as a godown, Forbes would have lived in the comfortable staff quarters on the first floor.

About 500 yards down the same street would have stood the warehouses of other European merchant companies, owned by the Portuguese, Dutch and the French. The Armenian settlement where Eliza would have lived began after that and the Armenian church would have been down the same street.

“The entire area would have had a radius of one kilometre. It would have been bordered by gardens, fountains and a red-light district from the Mughal era that existed in the old city till about a decade ago. Saudagarwada would have been a bustling place,” Meghani said.

[edit] Indian-Armenian marriages

The Telegraph, June 21, 2013

Meghani said that marriages between Armenian men and Indian women were uncommon but not unheard-of around the end of the 18th century.

“The community had been settled in India for over 500 years by then and was seen as close to the Mughal throne and hence powerful. So, intermarriages would not have been terribly frowned upon,” Meghani said.

The romance

In such a “happening” place, buzzing with pretty local girls and dashing merchants and sailors, the romance of Forbes and Eliza would have blossomed.

“And for what it is worth, the relationship seems to have been more than a bond of convenience,” Meghani suggested.

Despite the accepted norm of keeping mistresses, did the 23-year-old Forbes love a 19-year-old Eliza enough to make her his wife? “It seems he tried,” Meghani said.

“If British researchers say he may have married her in the Armenian church, it would have been a very honourable thing to do given that if he had not, no one would have raised a finger,” Meghani said.

According to the records, Forbes, when posted to Yemen soon after, took Eliza, pregnant with his daughter, along.