Brahman: 'Central Provinces'

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | ||

| + | This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in<br/>1916 its contents related only to Central India and did not claim to be true <br />of all of India. It has been archived for its historical value as well as for<br/>the insights it gives into British colonial writing about the various communities<br/>of India. Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this <br/> article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this <br/> article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about <br/> communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all. <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly <br/> on their online archival encyclopædia only after its formal launch. | ||

| + | |||

| + | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India|B]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Communities|B]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | ||

| + | From '''The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | By R. V. Russell | ||

| + | |||

| + | Of The Indian Civil Service | ||

| + | |||

| + | Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces | ||

| + | |||

| + | Assisted By | ||

| + | Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, | ||

| + | Extra Assistant Commissioner | ||

| + | |||

| + | Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh. ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

=Brahman= | =Brahman= | ||

LIST OP^ PARAGRAPHS | LIST OP^ PARAGRAPHS | ||

| Line 113: | Line 146: | ||

^ See also article Rajput-Gaur. | ^ See also article Rajput-Gaur. | ||

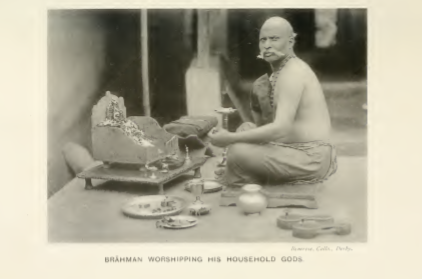

| − | [[File: | + | [[File: bramans1 .png| |frame|500px]] |

| Line 251: | Line 284: | ||

girl to a Kulin is said to have been so highly valued in | girl to a Kulin is said to have been so highly valued in | ||

^ Tribes and Castes, art. Brahman. | ^ Tribes and Castes, art. Brahman. | ||

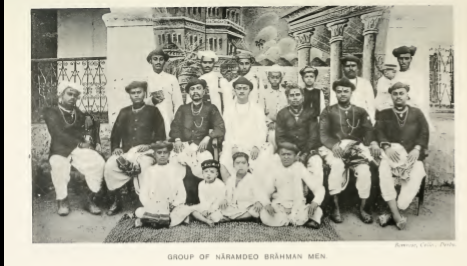

| − | [[File: braman2 | |frame|500px]] | + | [[File: braman2.png | |frame|500px]] |

Revision as of 17:43, 11 February 2014

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Brahman

LIST OP^ PARAGRAPHS Origin mid development of the caste. Their monopoly of literature. Absence of central authority. Mixed elements in the caste. Caste subdivisio7is. Miscellaneous groups. Sectarian divisions. 8. Exogamy. g. Restrictions on marriage. 0. Hypergamy. 1. Marriage customs. 1. Polygamy., divorce and treat- ment of widows. 1. Ahivasi. 2. Jijhotia. 3. Kanaujia, Kanyakubja. 4. Khedawal. 5. Maharashtra, Maratha. 6. Maithil. 13-

BRAHMAN

nearly 3 per cent of the population. This is less than the average strength for India as a whole, which is about 4^ per cent. The caste is spread over the whole Province, but is in greatest numbers in proportion to the population in Saugor and Jubbulpore, and weakest in the Feudatory States. The name Brahman or Brahma is said to be from the root brih or vrih, to increase. The god Brahma is con- sidered as the spirit and soul of the universe, the divine essence and source of all being. Brahmana, the masculine numerative singular, originally denoted one who prays, a worshipper or the composer or reciter of a hymn.^ It is the common term used in the Vedas for the officiating priest. Sir H. Risley remarks on the origin of the caste :

^ " The best modern opinion seems disposed to find the germ of the Brahman caste in the bards, ministers and family priests who were attached to the king's household in Vedic times. Different stages of this institution may be observed. In the earliest ages the head of every Aryan household was his own priest, and even a king would himself perform the sacrifices which were appropriate to his rank. By degrees families or guilds of priestly singers arose, who sought service under the kings, and were rewarded by rich presents for the hymns or praise and prayer recited and sacrifices offered by them on behalf of their masters. As time went on the sacrifices became more numerous and more elaborate, and the mass of ritual grew to such an extent that the king could no longer cope with it unaided. The employment of puroJdts or family priests, formerly optional, now became a sacred duty if the sacrifices were not to fall into disuse.

The Brfdiman obtained a monopoly of priestly functions, and a race of sacerdotal specialists arose which tended continually to close its ranks against the intrusion of out- siders." Gradually then from the household priests and those who made it their business to commit to memory and recite the sacred hymns and verses handed down orally from generation to generation through this agency, an 1 Crooke's Tribes and Castes, art. Brahmanism. Brahman, quoting Professor Eggol- ^ Tribes and Castes of Bengal, art. ing in Encyclopcedia Britannica, s.v. Braliman.

occupational caste emerged, which arrogated to itself the

monopoly of these functions, and the doctrine developed that nobody could perform them who was not qualified by birth, that is, nobody could be a Brahman who was not the son of a Brahman. When religious ritual became more important, as apparently it did, a desire would naturally arise among the priests to make their revered and lucrative profession a hereditary monopoly ; and this they were easily

and naturally able to do by only teaching the sacred songs and the sacrificial rules and procedure to their own de- scendants. The process indeed would be to a considerable extent automatic, because the priests would always take their own sons for their pupils in the first place, and in the

circumstances of early Indian society a married priesthood would thus naturally evolve into a hereditary caste.

The Levites among the Jews and the priests of the Parsis formed similar hereditary orders, and the reason why they did not arise in other great religions would appear to have been the prescription or encouragement of the rule of celibacy for the clergy and the foundation of monasteries, to which admission was free. But the military landed aristocracies of Europe practically formed hereditary castes which were analogous to the Brahman and Rajput castes, though of a less stereotyped and primitive character. The rise of the Brahman caste was thus perhaps a comparatively simple and natural product of religious and social evolution, and might have occurred independently of the development of the caste system as a whole.

The former might be accounted for by reasons which would be inadequate to explain the latter, even though as a matter of fact the same factors were at work in both cases. The hereditary monopoly of the sacred scriptures would 2. Their be strengthened and made absolute when the Sanskrit i"o"opoiy ° of litera- language, in which they had been composed and handed ture. down, ceased to be the ordinary spoken language of the people. Nobody then' could learn them unless he was taught by a Brahman priest. And by keeping the sacred literature in an unknown language the priesthood made their own position absolutely secure and got into their own hands the allocation of the penalties and rewards promised VOL. II 2 A

by religion, for which these books were the authority, that is to say, the disposal of the souls of Hindus in the after- life. They, in fact, held the keys of heaven and hell. The jealousy with which they guarded them is well shown by the Abbe Dubois

- ^ " To the Brahmans alone belongs

the right of reading the Vedas, and they are so jealous of this, or rather it is so much to their interest to prevent other castes obtaining any insight into their contents, that the Brahmans have inculcated the absurd theory, which is implicitly believed, that should anybody of any other caste be so highly imprudent as even to read the title-page his head would immediately split in two. The very few Brahmans who are able to read those sacred books in the original, only do so in secret and in a whisper.

Expulsion

from caste, without the smallest hope of re-entering it, would be the lightest punishment of a Brahman who exposed those

books to the eyes of the profane." It would probably be

unfair, however, to suppose that the Vedas were kept in the original Sanskrit simply from motives of policy.

It was probably thought that the actual words of the sacred text had themselves a concrete force and potency which would be lost in a translation. This is the idea underlying the whole class of beliefs in the virtue of charms and spells. But the Brahmans had the monopoly not only of the sacred Sanskrit literature, but practically of any kind of literacy or education.

They were for long the only literate section of the people. Subsequently two other castes learnt to read and write in response to an economic demand, the Kayasths and the Banias. The Kayasths, it has been suggested in the article on that caste, were to a large extent the offspring and inmates of the households of Brahmans, and were no doubt taught by them, but only to read and write the vernacular for the purpose of keeping the village records and accounts of rent. They were excluded from any knowledge of Sanskrit, and the Kayasths subsequently became an educated caste in spite of their Brahman pre- ceptors, by learning Persian under their Muhammadan, and English under their European employers.

The Banias never desired nor were encouraged to attain to any higher ' Hindu Manners^ Ciis/onis, and Ccretiionies, 3rd ed. p. 172. II AliSENCE OF CKNTRAL AUTHORITY 355 degree of literacy than that necessary for keeping accounts of sale and loan transactions. The Brahmans thus remained the only class with any real education, and acquired a monopoly not only of intellectual and religious leadership, but largely of public administration under the Hindu kings. No literature cxi.sted outside their own, which was mainly of a sacerdotal character ; and India had no heritage such as that bequeathed by Greece and Rome to mediaeval Europe which could produce a Renaissance or revival of literacy, leading to the Reformation of religion and the breaking of the fetters in which the Roman priesthood had bound the human mind. The Brahmans thus established, not only a complete religious, but also a social ascendancy which is only now beginning to break down since the British Government has made education available to all. The Brahman body, however, lacked one very important 3- Absence clement of strength.

They were apparently never organised authority. nor controlled by any central authority such as that which made the Roman church so powerful and cohesive. Colleges and seats of learning existed at Benares and other places, at which their youth were trained in the knowledge of religion and of the measure of their own pretensions, and the means by which these were to be sustained. But probably only a small minority can have attended them, and even these when they returned home must have been left practically to themselves, spread as the Brahmans were over the whole of India with no means of postal communication or rapid transit.

And by this fact the chaotic character of the Hindu religion, its freedom of belief and worship, its innumerable deities, and the almost complete absence of dogmas may probably be to a great extent explained. And further the Brahman caste itself cannot have been so strictly organised that outsiders and the priests of the lower alien religions never obtained entrance to it. As shown by Mr. Crooke, many foreign elements, both indi- viduals and groups, have at various times been admitted into the caste. The early texts indicate that Brahmans were in the 4. Mixed habit of forming connections with the widows of Raianyas elements m ° . -' -^ the caste. and Vaishyas, even if they did not take possession of the

wives of such men while they were still alive/ The sons of Angiras, one of the great ancestral sages, were Brahmans as well as Kshatriyas, The descendants of Garga, another well-known eponymous ancestor, were Kshatriyas by birth but became Brahmans. Visvamitra was a Kshatriya, who, by the force of his austerities, compelled Brahma to admit him into the Brahmanical order, so that he might be on a level with Vasishtha with whom he had quarrelled. Accord- ing to a passage in the Mahabharata all castes become Brahmans when once they have crossed the Gomti on a pilgrimage to the hermitage of Vasishtha." In more recent times there are legends of persons created Brahmans by Hindu Rajas. Sir J. Malcolm in Central India found many low-caste female slaves in Brahman houses, the owners of which had treated them as belonging to their own caste.^ It would appear also that in some cases the caste priests of different castes have become Brahmans.

Thus the Saraswat Brahmans of the Punjab are the priests of the Khatri caste. They have the same complicated arrangement of exogamy and hypergamy as the Khatris, and will take food from that caste. It seems not improbable that they are really descendants of Khatri priests who have become Brahmans.* Similarly such groups as the Oswal, Srimal and Palliwal Brahmans of Rajputana, who are priests of the subcastes of Banias of the same name, may originally have been caste priests and become Brahmans. The Naramdeo Brahmans, or those living on the Nerbudda River, are said to be descendants of a Brahman father by a woman of the Naoda or Dhlmar caste ; and the Golapurab Brahmans similarly of a Brahman father and Ahlr mother.

In many cases, such as the island of Onkar Mandhata in the Nerbudda in Nimar, and the Mahadeo caves at Pachmarhi, the places of worship of the non-Aryan tribes have been adopted by Hinduism and the old mountain or river gods transformed into Hindu deities. At the same time it is not improbable that the tribal priests of the old shrines have been admitted into the Brahman caste. ^ Muir, Ancient Sanskrit Texts, i. Quoted by Mr. Crooke. 282 sq. ^ Quoted in Mr. Crooke's Tribes ^ Tribes and Castes oj the Punjab, and Castes, art. Brahman. by Mr. H. A. Rose, vol. ii. p. 123.

The Brahman caste has ten main territorial divisions, 5. Caste forming two groups, the ranch-Gaur or five northern, and ^'jyjsions the Panch-Dravida or five southern. The boundary Hue between the two groups is supposed to be the Ncrbudda River, which is also the boundary between Hindustan and the Deccan. But the Gujarati Brahmans belong to the southern group, though Gujarat is north of the Nerbudda.

The five northern divisions are : {(i) Sdraswat. —^ These belong to the Punjab and are named after the Saraswati river of the classical period, on whose banks they are supposed to have lived. {])) Ganr.—The home of these is the country round Delhi, but they say that the name is from the old Gaur or Lakhnauti kingdom of Bengal. If this is correct, it is difficult to understand how they came from Bengal to Delhi contrary to the usual tendency of migration. General Cunningham has suggested that Gaura was also the name of the modern Gonda District, and it is possible that the term was once used for a considerable tract in northern India as well as Bengal, since it has come to be applied to all the northern Brahmans.

Kdnkubja or Kanaujia

These are named after the old town of Kanauj on the Ganges near Cawnpore, once the capital of India. The Kanaujia are the most important of the northern groups and extend from the west of Oudh to beyond Benares and into the northern Districts of the Central Provinces. Here they are subdivided into four principal groups—the Kanaujia, Jijhotia, Sarwaria and Sanadhya, which are treated in annexed subordinate articles. {d) Maithil.—They take their name from Mithila, the old term for Bihar or Tirhut, and belong to this tract. {e) Utkal.—These are the Brahmans of Orissa.

The five groups of the Panch-Dravida are as follows : ia) Maharashtra.—These belong to the Maratha country or Bombay. They are subdivided into three main terri- torial groups—the Deshasth, or those of the home country, that is the Poona tract above the Western Ghats ; the Konkonasth, who belong to the Bombay Konkan or littoral

^ See also article Rajput-Gaur.

and the Karhara, named after a place in the Satara

District.^ ib) Tailanga or AndJira.—The Brahmans of the Telugu country, Hyderabad and the northern part of Madras. This territory was known as Andhra and governed by an important dynasty of the same name in early times. (r) Drdvida.—The Brahmans of the Tamil country or the south of Madras, id) Karndta.—The Brahmans of the Carnatic, or the Canarese country. The Canarese area comprises the Mysore State, and the British Districts of Canara, Dharwar and

Belgaum. {e) Gurjara.—The Brahmans of Gujarat, of whom two subcastes are found in the Central Provinces. The first consists of the Khedawals, named after Kheda, a village in Gujarat, who are a strictly orthodox class holding a good position in the caste.

And the second are the Nagar Brahmans, who have been long settled in Nimar and the adjacent tracts, and act as village priests and astrologers. Their social status is somewhat lower. There are, however, a large number of other subcastes, and the tendency to fissure in a large caste, and to the formation of small local groups which marry among them- selves, is nowhere more strikingly apparent than among the Brahmans. This is only natural, as they, more than any other caste, attach importance to strict ceremonial observance in matters of food and the daily ritual of prayer, and any group which was suspected of backsliding in respect of these on emigration to a new locality would be debarred from intermarriage with the parent caste at home.

An instance of this is found among the Chhattlsgarhi Brahmans, who have been long settled in this backward tract and cut off from communication with northern India. They are mainly of the Kanaujia division, but the Kanaujias of Oudh will neither take food nor intermarry with them, and they now constitute a separate subcaste of Kanaujias. Similarly the Malwi Brahmans, whose home is in Malwa, whence they have spread to Hoshangabad and Betul, are believed to have been originally a branch of the Gaur or Kanaujia, ' Sec subordinate articles. II MISCELLANEOUS GROUPS 359 but have now become a distinct subcastc, and have adopted many of the customs of Maratha Brfdimans. Mandla contains a colony of Sarwaria ' Brahmans who received grants of villages from the Gond kings and have settled down there. They are now cultivators, and some have taken to the plough, while they also permit widow-remarriage in all but the name. They arc naturally cut off from intercourse with the orthodox Sarwarias and marry among themselves.

The Harenia Brahmans of Saugor arc believed to have immigrated from Hariana some generations ago and form a separate local group ; and also the Laheria Brahmans of the same District, who, like the Mandla Sarwarias, permit widows to marry. In Hoshangabad there is a small sub- caste of BawTsa or ' Twenty-two ' Brahmans, descended from twenty-two families from northern India, who settled here and have since married among themselves.

A similar diversity of subcastes is found in other Provinces. The Brahmans of Bengal are also mainly of the Kanaujia division, but they are divided into several local subcastes, of which the principal are Rarhi and Barendra, named after tracts in Bengal, and quite distinct from the subdivisions of the Kanaujia group in the Central Provinces. Another class of local subdivisions consists of those e. Miscei- Brahmans who live on the banks of the various sacred rivers '^"^o^s , . groups, or at famous shrmes, and earn their livelihood by conducting pilgrims through the series of ceremonies and acts of wor- ship which are performed on a visit to such places ; they receive presents from the pilgrims and the offerings made at the shrines. The most prominent among these are the Gayawals of Gaya, the Prayagwals of Allahabad (Prayag), the Chaubes of Mathura, the Gangaputras (Sons of the Ganges) of Benares, the Pandarams of southern India and the Naramdeo Brahmans who hold charge of the many temples on the Nerbudda. As such men accept gifts from pilgrims they are generally looked down on by good Brahmans and marry among themselves. Many of them have a character for extortion and for fleecing their clients, a propensity commonly developed in a profession of this kind.

Such a reputation particularly attaches to the Chaubes of Mathura 1 A section of the Kanaujia. See above.

and Brindaban, the holy places of the god Krishna. They are strong and finely built men, but gluttonous, idle and dissolute. Some of the Benares Brahmans are known as Sawalakhi, or having one and a quarter lakhs, apparently on account of the wealth they amass from pilgrims, A much lower group are the Maha-Brahmans (great Brah- mans), who are also known as Patit (degraded) or Katia. These accept the gifts offered by the relatives after a death for the use of the dead man in the next world during the period of mourning ; they also eat food which it is supposed will benefit the dead man, and are considered to represent him. Probably on this account they share in the impurity attaching to the dead, and are despised by all castes and sometimes not permitted to live in the village. Other Brahmans are degraded on account of their having partly adopted Muhammadan practices. The Husaini Brahmans of western India are so called as they combine Muhammadan with Hindu rites. They are principally beggars.

And the Kalanki Brahmans of Wardha and other Districts are looked down upon because, it is said, that at the bidding of a Muhammadan governor they make a figure of a cow from sugar and eat it up. Probably they may have really acted as priests to Muhammadans who were inclined to adopt certain Hindu rites on the principle of imitation, and with a view to please their disciples conformed to some extent to Islam. 7. Sect- Brahmans have also sectarian divisions according to the sions '^' different Vedas, which they especially study. It is held that the ancient Rishis or saints, like the Jewish patriarchs, lived far beyond the ordinary span of existence, and hence had time to learn all the Vedas and their commentaries. But this was impossible for their shorter-lived descendants, and hence each Veda has been divided into a number of Shakhas or branches, and the ordinary Brahman only learns one Shakha of one Veda. Most Brahmans of the Central Provinces are either Rigvedis or Yajurvedis, and these commonly marry only followers of their own Veda, thus forming a sort of cross set of endogamous divisions. The restriction on marriage may also extend to the Shakha, so that a man can only marry in a family of the same Shakha

as himself. This applies in the Central Provinces mainly to the Yajurvcclis, who have three well-known Shakhas or branches called Kannava, Apastambha and Madhyandina. These are derived from the Shukla or White Yajurveda, which can be understood, while the Black Yajurveda is obscure and unintelligible. The Rigvedis and Yajurvedis have some differences in their methods of recitation.

The Rigvedis are said to move the head up and down when they recite and not to use the hands ; while the Yajurvedis swing the hands and body from side to side. It is said that a Madhyandina cannot say his prayers nor take his food before midday, and hence the name, which means half the day. These points of distinction are given as stated by the local Brahmans, and it is not known whether they would be endorsed by the Pandits. The Maratha Brahmans of the Central Provinces are usually Rigvedis and the Kanaujia Brahmans Yajurvedis. Followers of the other two Vedas are practically not found. Among Kanaujia Brahmans it is also customary to ask the head of a family with which a marriage is proposed whether he ties a knot in the right or left half of his Shikha or scalp-lock during his prayers and whether he washes his right or left foot first in the perform- ance of a religious ceremony. The exogamous arrangements of the Brahmans are also s.

Exo- very complex. It is said that the Brahmans are descended s^my- from the seven sons of the god Brahma, who were Bhrigu, Angirasa, Marichi, Atri, Pulaha, Pulastya and Vasishtha. But Pulaha only begot demons and Pulastya giants, while Vasishtha died and was born again as a descendant of Marichi. Consequently the four ancestors of the Brahmans were Bhrigu, Angirasa, Marichi and Atri. But according to another account the ancestors of the Brahmans were the seven Rishis or saints who form the constellation of the Great Bear. These were Jamadagni, Bharadwaj, Gautam, Kashyap, Vasishtha, Agastya, Atri and Visvamitra, who makes the eighth and is held to be descended from Atri. These latter saints are also said to be the descendants of the four original ones, Atri appearing in both lists. But the two lists taken together make up eleven great saints, who were the eponymous ancestors of the Brahmans.

All the

9. Restric- tions on marriage. different subcastes have as a rule exogamous classes tracing their descent from these saints. But each group, such as that of Bhrigu or Angirasa, contains a large number of exo- gamous sections usually named after other more recent saints, and intermarriage is sometimes prohibited among the different sections, which are descended from the same son of Brahma or star of the Great Bear. The arrangement thus bears a certain resemblance to the classification system of exogamy found among primitive races, only that the number of groups is now fairly large ; but it is said that originally there were only four, from the four sons of Brahma who gave birth to Brahmans.

The names of other important saints, after whom exogamous sections are most commonly called, are Garg, Sandilya, Kaushik, Vatsya and Bhargava.

These five appear sometimes to be held as original ancestors in addition to the eleven already mentioned. It may be noted that some of the above names of saints have a totem- istic character ; for instance, Bharadwaj means a lark ; Kashyap resembles Kachhap, the name for a tortoise ; Kaushik may come from the kusJia grass ; Agastya from the agasti flower, and so on. Within the main group exogamy sometimes also goes by titles or family names.

Thus the principal titles of the Kanaujias are : Pande, a wise man ; Dube, learned in two Vedas ; Tiwari, learned in three Vedas ; Chaube, learned in four Vedas ; Sukul, white or pure ; Upadhya, a teacher ; Agnihotri, the priest who performs the fire-sacrifice ; Dikshit, the initiator, and so on. Marriage between persons bearing the same family name tends to be prohibited, as they are considered to be relations. The prohibition of marriage within the gotra or exo- gamous section bars the union of persons related solely through males. In addition to this, according to Hindu law a Brahman must not marry a girl of his mother's or maternal grandfather's gotra, or one who is a sapinda of his father or maternal grandfather.

Mr. Joshi states that sapindas are persons related through being particles of the same body. It is also understood that two persons are said to be sapindas when they can offer pindas or funeral cakes to the same ancestor. The rule barring the marriage of sapindas is that two persons cannot marry if they are

both as near as fourth in descent from a common ancestor, and the relationship is derived through the father of either party. If either is more remote than fourth in descent they apparently could marry. If the relationship of the couple is through their mothers in each case, then they cannot marry if they are third in descent from the same ancestor, but may do so in the fourth or subsequent genera- tions.

It is of no importance whether the intervening links between the common ancestor and the proposed couple are male or female ; descent is considered to be male if through the father, and female if through the mother. In practice, marriages are held to be valid between persons fourth in descent from a common ancestor in the case of male relationship, and third in the case of female relationship, that is, persons having a common greatgrandparent in the male line or a common grandparent in the female line can marry. Other rules are that girls must not be exchanged in marriage between two families, and a man may not marry two sisters, though he can marry his deceased wife's sister.

The bride should be both younger in age and shorter in stature than the bridegroom. A younger sister should not be married while her elder sister is single. The practice of hypergamy is, or was until recently, 10. Hyper common among Brahmans. This is the rule by which the ^^™^' social estimation of a family is raised if its girls are married into a class of higher social status than its own. Members of the superior classes will take daughters from the lower classes on payment usually of a substantial bride-price, but will not give their daughters to them. According to Manu, men of the higher castes were allowed to take wives from the lower ones but not to give daughters to them.

The origin of the custom is obscure. If caste was based on distinctions of race, then apparently the practice of hypergamy would be objectionable, because it would destroy the different racial classes. If, on the other hand, the castes consisted of groups of varying social status, the distinction being that those of the lower ones could not participate in the sacramental or communal meals of the higher ones, then the marriage of a daughter into a higher group, which would carry with it participation at the sacramental marriage

feast of this group, might well be a coveted distinction. The custom of hypergamy prevails somewhat largely in northern India between different subcastes, groups of different social status in the same subcaste, and occasion- ally even between different castes.

The social results of hypergamy, when commonly practised, are highly injurious. Men of the higher subcastes get paid for marrying several wives, and indulge in polygamy, while the girls of the higher subcastes and the boys of the lower ones find it difficult and sometimes even impossible to obtain husbands and wives. The custom attained its most absurd development among the Kulin Brahmans of eastern Bengal, as described by Sir H. Risley.^ Here the Brahmans were divided by a Hindu king, Ballal Sen, into two classes, the Kulin (of good family), who had observed the entire nine counsels of perfection ; and the Srotriya, who, though regular students of the Vedas, had lost sanctity by intermarrying with families of inferior birth.

The latter were further sub- divided into three classes according to their degree of social purity, and each higher class could take daughters from the next one or two lower ones. The doctrine known as Kula-gotra was developed, whereby the reputation of a family depended on the character of the marriages made by its female members. In describing the results of the system Sir H. Risley states : " The rush of competition for Kulin husbands on the part of the inferior classes became acute. In order to dispose of the surplus of women in the higlier groups polygamy was resorted to on a very large scale :

it was popular with the Kulins because it enabled them to make a handsome income by the accident of their birth ; and it was accepted by the parents of the girls concerned as offering the only means of complying with the require- ments of the Hindu religion. Tempted by a pan or premium, which often reached the sum of two thousand rupees, Swabhava Kulins made light of their kid and its obligations, and married girls, whom they left after the ceremony to be taken care of by their parents. Matrimony became a sort of profession, and the honour of marrying a girl to a Kulin is said to have been so highly valued in ^ Tribes and Castes, art. Brahman.

eastern Bengal that as soon as a boy was ten years old

his friends began to discuss his matrimonial prospects, and before he was twenty he had become the husband of many wives of ages varying from five to fifty." The wives were commonly left at home to be supported by their parents, and it is said that when a Kulin Brahman had a journey to make he usually tried to put up for the night at the

house of one of his fathers-in-law. All the marriages were

recorded in the registers of the professional Ghataks or marriage -brokers, and each party was supplied with an extract. On arrival at his father-in-law's house the Kulin

would produce his extract showing the date on which his marriage took place ; and the owner of the house, who was often unfamiliar with the bridegroom's identity, would com- pare it with his own extract.

When they agreed he was taken in and put up for the night, and enjoyed the society of his wife. The system thus entailed the greatest misery to large numbers of women, both those who were married to husbands whom they scarcely ever saw, and those of the higher classes who got no husbands at all. It is now rapidly falling into abeyance. Hypergamy is found in the Central Provinces among the subcastes of Kanaujia Brahmans. The Sarwaria subcaste, which is the highest, takes daughters from Kanaujias and Jijhotias, and the Kanaujias take them from the Jijhotias.

These and other subcastes such as the Khedawals are also often divided into two groups of different status, the higher of which takes daughters from the lower. Usually the parents of the girl pay a liberal bridegroom-price in money or ornaments. It has never, however, been carried to the same length here as in Bengal, and two, or in some cases three, wives are the limit for a man of the higher classes. One division of Kanaujias is called the Satkul or seven families, and is the highest. Other Kanaujias, who are known as Pachhadar, pay substantial sums for husbands for this group, and it is reported that if such a marriage takes place and the bridegroom- price is not paid up, the husband will turn his wife out and send her home to her father. Certain subcastes of Sunars also have hypergamy and, as between different castes, it exists between the Dangis and Rajputs, pure Rajputs being nage customs

held willing to take daughters in marriage from the highest clans of Dangis. II. Mar- A text of Manu prescribes : ^ " If a young woman marry while she is pregnant, whether her pregnancy be known or unknown, the male child in her womb belongs to the bride- groom and is called a son received with his bride," But at present a Brahman girl who is known to be pregnant will be wholly debarred from the sacrament of marriage. An invitation to a wedding is sent by means of grains of rice coloured yellow with turmeric and placed in a brass bowl with areca-nuts over them. All the members of the caste or subcaste who eat food with the host and are resident in the same town or close at hand are as a rule invited, and all relatives of the family who reside at a distance.

The head of the family goes himself to the residence of the guests and invites them with expressions of humility to honour his home. Before the wedding the ancestors of the family and also the divine mothers are worshipped, these latter con- sisting of the consorts of the principal gods. In front of the wedding procession are carried kalasJias or earthen jars filled to the brim with water, and with green shoots and branches floating on the top.

The kalasJia is said to represent the universe and to contain the principal gods and divine mothers, while the waters in it are the seven seas. All these are witnesses to the wedding. Among other ceremonies, presents of fruit, food, ornaments and jewellery are exchanged between the parties, and these are called cJwli-ka-bJiardna or filling the bride's breast -cloth. The original object of giving these presents was thus, it would appear from the name, to render the bride fertile. The father then gives his daughter away in a set form of speech. After reciting the exact moment of time, the hour, the day, the minute according to solar and lunar reckoning, the year and the epoch, he proceeds

- "In the name of Vishnu (repeating the name three times), the supreme spirit, father and creator of the universe, and in furtherance of his wish for the propagation of the human species, I (specifying his full name and section, etc.), in the company of my married wife, do hereby offer the hand of my daughter—may she live

' Chap. ix. V. 173. II MARKIACE CUSTOMS 367 long—full of all virtuous qualities, image of Lakshmi, wife of Vishnu, anxious of union in lawful wedlock, ornamented and dressed, brought up and instructed according to the best of my means, by name (naming her and repeating the full description of ancestors, class, etc.) in the solemn presence of the Brahmans, Gurus, fire and deities, to you—may you live long—(repeating the bridegroom's name and full description), anxious to obtain a wife with a view to secure the abode of bliss and eternal happiness in the heaven of Brahma. Accept her with kusha grass, grains of rice, water and presents of money." Afterwards the father asks the bridegroom never to disregard the feelings and senti- ments of his wife in matters of religion, social pleasures and the acquisition of money, and the bridegroom agrees.

The binding portion of the ceremony consists in walking seven times round the sacred post, and when the seventh round is completed the marriage is irrevocable. Among the Maratha Brahmans the bridegroom is called Nawar Deo or the new god. During the five days of the wedding he is considered to be a sort of king, and is put in the highest place, and everybody defers to him. They make the bridegroom and bride name each other for a joke, as they are ashamed to do this, and will not untie their clothes to let them bathe until they have done it.

At all the feasts the bride and bridegroom are made to eat out of the same plate, and they put pieces of food in each other's mouth, which is supposed to produce affection between them. The wedding expenses in an ordinary Kanaujia Brahman's family, whose income is perhaps Rs. 20 to 40 a month, are estimated at Rs. 200 for the bridegroom's party and Rs. 175 for the bride's, exclusive of any bride- or bridegroom-price.

The bulk of the expendi- ture is on feasts to the caste. The bride does not live with her husband until after she arrives at puberty, but it is thought desirable that she should spend long visits with his family before this, in order that she may assimilate their customs and be trained by her mother-in-law, according to the saying, ' Tender branches are easily bent' Among some Maratha Brahmans, when the bride arrives at puberty a ceremony called Garhbhadan is performed, and the husband confesses whether he has cohabited with his wife 368 BRAHMAN 12. Poly- gamy, divorce and treat- ment of widows. before her puberty, and if so, he is fined a small sum. Such instances usually occur when the signs of puberty are delayed. If the planet Mangal or Mars is adverse to a girl in her horoscope, it is thought* that her husband will die. The women of her family will, therefore, first marry her secretly to a pipal-tree, so that the tree may die instead. But they do not tell this to the bridegroom. In Saugor, girls whose horoscope is unfavourable to the husband are first married to the arka or swallow-wort plant. If a Brahman has not sufficient funds to arrange for the marriage of his daughter he will go about and beg, and it is considered that alms given for this purpose acquire special merit for the donor, nor will any good Brahman refuse a contribution according to his means. Polygamy conveys no stigma among Brahmans, but is uncommon. Divorce is not recognised, a woman who is put away by her husband being turned out of the caste. The remarriage of widows is strictly prohibited. It is said that marriage is the only sacrament (Sanskar) for a woman, and she can only go through it once. The holy nuptial texts may not be repeated except for a virgin. The prohibition of the remarriage of widows has become a most firmly rooted prejudice among the higher classes of Hindus, and is the last to give way before the inroads of liberal reform. Only a small minority of the most advanced Brahmans have recognised widow-remarriage, and these are generally held to be excluded from the caste, though breaches of the rules against the consumption of prohibited kinds of meat, and the drinking of aerated waters and even alcoholic liquor, are now winked at and not visited with the proper penalty. Nevertheless, many classes of Brahmans, who live in the country and have taken to cultivation, allow widows to live with men without putting the family out of caste. Where this is not permitted, surreptitious intercourse may occasion- ally take place with members of the family. The treatment of widows is also becoming more humane. Only Maratha and Khedawal Brahmans in the Central Provinces still force them to .shave their heads, and these will permit a child- widow to retain her hair until she grows up, though they regard her as impure while she has it. A widow is usually 11 SATI OR liURNING OF ll'/DOlVS 369 forbidden to have a cot or bed, and must sleep on the ground or on a plank. She may not chew betel-leaves, should eat only once a day, and must rigorously observe all the prescribed fasts. She wears while clothes only, no glass bangles, and no ornaments on her feet. She is subject to other restrictions and is a general drudge in the family. It is probable that the original reason for such treatment of a widow was that she was considered impure through being perpetually haunted by her husband's ghost.

Hindus say that a widow is half- dead. She should not be allowed to cook the household food, because while cooking it she will remember her husband and the food will become like a corpse. The smell of such food will offend the gods, and it cannot be offered to them. A widow is not permitted to worship the household god or the ancestors of the family. It was no doubt an advantage under the joint family system that a widow should not claim any life -interest in her husband's property.

The modern tendency of widows, who are left in possession, to try and alienate the property from the husband's relatives has been a fruitful cause of litigation and the ruin of many old landed families. The severe treatment of widows was further calculated to suppress any tendency on the part of wives to poison their husbands. These secondary grounds may have contributed something to the preservation and enforcement of an idea based origin- ally on superstitious motives. For a widow to remain single and lead an austere and 13. Sati or joyless life was held to confer great honour on her family ; |^."^o^"f °^ and this was enormously enhanced when she decided to become sati and die with her husband on the funeral pyre.

Though it is doubtful whether this practice is advocated by the Vedas, subsequent Hindu scriptures insist strongly on it. It was said that a widow who was burnt with her husband would enjoy as many years in paradise as there are hairs on the human head, that is to say, thirty-five million. Con- versely, one who insisted on surviving him would in her next birth go into the body of some animal. By the act of sati she purified all her husband's ancestors, even from the guilt of killing a Brahman, and also those of her own family. If a man died during an absence from home in another VOL. II 2 B

country his wife was recommended to take his slippers or any other article of dress and burn herself with them tied to her breast.^ Great honour was paid to a Sati, and a temple or memorial stone was always erected to her at which her spirit was venerated, and this encouraged many pious women not only to resign themselves to this terrible death but ardently to desire it.

The following account given by Mr. Ward of the method of a sati immolation in Bengal may be reproduced : ^ " When the husband's life is despaired of and he is carried to the bank of the Ganges, the wife declares her resolution to be burnt with him. In this case she is treated with great respect by her neighbours, who bring her delicate food, and when her husband is dead she again declares her resolve to be burnt with his body. Having broken a small branch from a mango tree she takes it with her and proceeds to the body, where she sits down.

The barber then paints the sides of her feet red, after which she bathes and puts on new clothes. During these preparations the drum beats a certain sound by which it is known that a widow is about to be burnt with the corpse of her husband. A hole is dug in the ground round which posts are driven into the earth, and thick green stakes laid across to form a kind of bed ; and upon these are laid in abundance dry faggots, hemp, clarified butter and pitch. The officiating Brahman now causes the widow to repeat the prayer that as long as fourteen Indras reign, or as many years as there are hairs on her head, she may abide in heaven with her husband

that during this time the heavenly dancers may wait on her and her husband ; and that by this act of merit all the ancestors of her mother and husband may ascend to heaven. She now presents her ornaments to her friends, ties some red cotton on both wrists, puts two new combs in her hair, paints her forehead, and takes into the end of the cloth that she wears some parched rice and cowries.

The dead body is bathed, anointed with butter, and dressed in new clothes. The son takes a handful of boiled rice and offers it in the name of his deceased father. Ropes and another piece of ^ Ward's Hiftdus, vol. ii. p. 97. - Ibidem, pp. 98, 100. II SATI OR BURNING OF WJDOll'S 371 cloth are spread on the wood, and the dead body is laid upon the pile. The widow next walks round the pyre seven times, as she did round the marriage-post at her wedding, strewing parched rice and cowries as she goes, which the spectators catch and keep under the belief that they will cure diseases. The widow then lies down on the fatal pile by the side of the dead body.

The bodies arc bound together with ropes and the faggots placed over them. The son, averting his head, puts fire to the face of his father, and at the same moment several persons light the pile at different sides, when the women and mourners set up cries. More faggots are hastily brought and thrown over the pile, and two bamboo levers are pressed over them to hold down the bodies and the pile. Several persons are employed in holding down these levers. More clarified butter, pitch and faggots are thrown on to the pile till the bodies are con- sumed.

This may take about two hours, but I conceive the woman must be dead in a few minutes after the fire has been kindled." As showing the tenacity with which women sometimes adhered to their resolve to be burned with their husbands, and thus, as they believed, resume their conjugal life in heaven, the following account by Sir William Sleeman, in his Rambles and Recollections^ of a sati at Jubbulpore may be given : "

At Gopalpur on the Nerbudda are some very pretty temples built for the most part to the memory of women who have burned themselves with the remains of their husbands, and on the very spot where the cremation occurred. Among them was one recently raised over the ashes of one of the most extraordinary old bodies I had ever seen, who burned herself in my presence in 1829. In March 1828 I had issued a proclamation prohibiting any one from aiding or assisting in sati, and distinctly stating that to bring one ounce of wood for the purpose would be considered as so doing. Subsequently, on Tuesday, 24th November,

I had an application from the heads of the most respectable and most extensive family of Brahmans in the District, to suffer this old woman to burn herself with the remains of her husband, Umeid Singh Upadhya, who had that morning died upon the banks of the Nerbudda. I threatened to

enforce my order and punish severely any man who assisted ; and placed a police guard for the purpose of seeing that no one did so. The old woman remained by the edge of the water without eating or drinking. Next day the body of her husband was burned in the presence of several thousand spectators, who had assembled to see ^he.* sati. The sons and grandsons of the old woman remained with her, urging her to desist from her resolve, while her other relatives surrounded my house urging me to allow her to burn.

All the day she remained sitting upon a bare rock in the bed of the Nerbudda, refusing every kind of sustenance, and exposed to the intense heat of the sun by day and the severe cold of the night, with only a thin sheet thrown over her shoulders. On the next day, Thursday, to cut off all hope of her being moved from her purpose, she put on the dhujja or coarse red turban and broke her bracelets in pieces, by which she became dead in law and for ever excluded from caste. Should she choose to live after this she could never return to her family. On the morning of Saturday, the fourth day after the death,

I rode out ten miles to the spot, and found the poor old widow sitting with the dhujja round her head, a brass plate before her with undressed rice and flowers, and a cocoanut in each hand. She talked very collectedly, telling me that she had determined to mix her ashes with those of her departed husband, and should patiently await my permission to do so, assured that God would enable her to sustain life till that was given, though she dared not eat or drink. Looking at the sun, then rising before her over a long and beautiful reach of the Nerbudda, she said calmly : ' My soul has been for five days with my husband's near that sun ; nothing but my earthly frame is left, and this I know you will in time suffer to be mixed with the ashes of his in yonder pit, because it is not in your nature wantonly to prolong the miseries of a poor old woman.' I told her that my object and duty was to save and preserve her ; I was come to urge her to live and keep her family from the disgrace of being thought her murderers. I tried to work upon her pride and fears. I told her that the rent- free lands on which her family had long subsisted might be resumed by Government if her children permitted her to do II SATI OR miRNINC, O/' 117/)01VS 373 lliis act ; and that no brick or stone should ever mark the place of her death ; but if she would live, a splendid habita- tion should be made for her among the temples, and an allowance given her from the rent-free lands. She smiled, but held out her arm and said, ' My pulse has long ceased to beat, for my spirit has departed, and I have nothing left but a little earth that I wish to mix with the ashes of my husband.

I shall suffer nothing in burning, and if you wish proof order some fire, and you shall see this arm consumed without giving me any pain.' I did not attempt to feel her pulse, but some of my people did, and declared that it had ceased to be perceptible. At this time every native present believed that she was incapable of suffering pain, and her end confirmed them in their opinion. Satisfied myself that it would be unavailing to attempt to save her life, I sent for all the principal members of the family, and consented that she should be suffered to burn herself if they would enter into engagements that no other member of their family should ever do the same.

This they all agreed to, and the papers having been drawn out in due form about midday, I sent down notice to the old lady, who seemed extremely pleased and thankful. The ceremonies of bathing were gone through before three, while the wood and other combustible materials for a strong fire were collected and put into the pit. After bathing she called for a fan (betel-leaf) and ate it, then rose up, and with one arm on the shoulder of her eldest son, and the other on that of her nephew, approached the fire. As she rose up fire was set to the pile, and it was instantly in a blaze. The distance was about one hundred and fifty yards ; she came on with a calm and cheerful countenance, stopped once, and casting her eyes upwards said, ' Why have they kept me five days from thee, my husband ? ' On coming to the sentries her supports stopped, she walked round the pit, paused a moment ; and while muttering a prayer threw some flowers into the fire.

She then walked deliberately and steadily to the brink, stepped into the centre of the flame, sat down, and leaning back in the midst as if reposing upon a couch, was consumed without uttering a shriek or betraying one sign of agony." In cases, however, where women shrank from the flames rites and mourning,

they were frequently forced into them, as it was a terrible disgrace to their families that they should recoil on the scene of the sacrifice. Opium and other drugs were also ad- ministered to stupefy the woman and prevent her from feeling pain. Widows were sometimes buried alive with their dead husbands.

The practice of sati was finally prohibited in 1829, without exciting the least discontent. 14. Funeral The bodics of children dying before they are named, or before the tonsure ceremony is performed on them, are buried, and those of other persons are burnt. In the grave of a small child some of its mother's milk, or, if this is not available, cow's milk in a leaf-cup or earthen vessel, is placed. Before a body is burnt cakes of wheat-flour are put on the face, breast and both shoulders, and a coin is always deposited for the purchase of the site. Mourning or impurity is observed for varying periods, according to the nearness of relationship. For a child, relatives other than the parents have only to take a bath to remove the impurity caused by the death.

In a small town or village all Brahmans of the same subcaste living in the place are impure from the time of the death until cremation has taken place. After the funeral the chief mourner performs the sJirdddJi ceremony, offering piiidas or cakes of rice, with libations of water, to the dead. Presents are made to Brahmans for the use of the dead man in the other world, and these are sometimes very valuable, as it is thought that the spirit will thereby be profited. Such presents are taken by the Maha-Brahman, who is much despised. When a late zamlndar of Khariar died, Rs. 2000 were given to the Maha-Brahman for the use of his soul in the next world. The funeral rites are performed by an ordinary Brahman, known as Malai, who may receive presents after the period of impurity has expired.

Formerly a calf was let loose in the name of the deceased after being branded with the mark of a trident to dedicate it to Siva, and allowed to wander free thenceforth. Sometimes it was formally married to three or four female calves, and these latter were presented to Brahmans. Some- times the calf was brought to stand over the dying man and water poured down its tail into his mouth. The practice of letting loose a male calf is now declining, as these animals II FUNERAL RIIRS AND MOURNING 375 arc a great nuisance to the crops, and cultivators put them in the pound. The calf is therefore also presented to a Brfdiman.

It is believed that the sJirdddJi ceremony is necessary to unite the dead man's spirit with the Pitris or ancestors, and without this it wanders homeless. Some think that the ancestors dwell on the under or dark side of the moon. Those descendants who can offer the pindas or funeral cakes to the same ancestor are called Sapindas or relatives, and the man who fills the office of chief mourner thereby becomes the dead man's heir. Persons who have died a violent death or have been executed are not entitled to the ordinary funeral oblations, and cannot at once be united with the ancestors.

But one year after the death an effigy of the deceased person is made in kusha grass and burnt, with all the ordinary funeral rites, and offerings are made to his spirit as if he had died on this occasion. If the death was caused by snake-bite a gold snake is made and presented to a Brahman before this ceremony is begun. This is held to be the proper funeral ceremony which unites his spirit with the ancestors. Formerly in Madras if a man died during the last five days of the waning of the moon it was considered very unlucky. In order to escape evil effects to the relatives a special opening was made in the wall of the house, through which the body was carried, and the house itself was afterwards abandoned for three to six months.

A similar superstition prevails in the Central Provinces about a man dying in the Mul Nakshatra or lunar asterism, which is perhaps the same or some similar period. In this case it is thought that the deaths of four other members of the household are portended, and to avert this four human figures are made of flour or grass and burnt with the corpse.

According to the Abbe Dubois if a man died on a Saturday it was thought that another death would occur in the family, and to avert this a living animal, such as a ram, goat or fowl, was offered with the corpse.^ The religion of the Brahmans is Hinduism, of which 15. Reii- they are the priests and exponents. Formerly the Brahman ^'°"" considered himself as a part of Brahma, and hence a god. ^ Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies, by the Abbe Dubois, 3rd ed. p. 499. 2 Ibidem, p. 500. ritual

This belief has decayed, but the gods are still held to reside in the body ; Siva in the crown of the head, Vishnu in the chest, Brahma in the navel, Indra in the genitals and Ganesh in the rectum. Most Brahmans belong to a sect worshipping especially Siva or Vishnu, or Rama and Krishna, the incarnations of the latter god, or Sakti, the female principle of energy of Siva. But as a rule Brahmans, whether of the Sivite or Vishnuite sects, abstain from flesh meat and are averse to the killing of any living thing.

The following account of the daily ritual prayers of a Benares Brahman may be reproduced from M. Andre Chevrillon's Romantic India} as, though possibly not altogether accurate in points of detail, it gives an excellent idea of their infinitely complicated nature

16. Daily " Here is the daily life of one of the twenty-five thousand Brahmans of Benares. He rises before the dawn, and his first care is to look at an object of good omen. If he sees a crow at his left, a kite, a snake, a cat, a hare, a jackal, an empty jar, a smoking fire, a wood-pile, a widow, a man blind of one eye, he is threatened with great dangers during the day. If he intended to make a journey, he puts it off. But if he sees a cow, a horse, an elephant, a parrot, a lizard, a clear-burning fire, a virgin, all will go well.

If he should sneeze once, he may count upon some special good fortune ; but if twice some disaster will happen to him. If he yawns some demon may enter his body. Having avoided all objects of evil omen, the Brahman drops into the endless routine of his religious rites. Under penalty of rendering all the day's acts worthless, he must wash his teeth at the bank of a sacred stream or lake, reciting a special mantra, which ends in this ascription : ' O Ganges, daughter of Vishnu, thou springest from Vishnu's foot, thou art beloved by him ! Remove from us the stains of sin and birth, and until death protect us thy servants ! ' He then rubs his body with ashes, saying : ' Homage to Siva, homage to the source of all birth ! May he protect me during all births ! ' He traces the sacred signs upon his forehead—the three vertical lines representing the foot of Vishnu, or the three horizontal lines which symbolise the ^ London, Ileinemann (1897), pp. 84-91. u DAILY RITUAL 377 trident of Siva —and twists into a knot the hair left by the razor on the top of his head, that no im[)urity may fall from it to pollute the sacred river. " He is now ready to begin the ceremonies of the morning {sandhya), those which I have just observed on the banks of the river. Minutely and mechanically each Brahman performs by himself these rites of prescribed acts and gestures. First the internal ablution : the worshipper takes water in the hollow of his hand, and, letting it fall from above into his mouth, cleanses his body and soul. Mean- while he mentally invokes the names of Vishnu, saying,

' Glory to Keshava, to Narayana, to Madhava, to Govinda,'

and so on. " The second rite is the exercise or ' discipline ' of the respiration {prajayavia). Here there are three acts : first,

the worshipper compresses the right nostril with the thumb,

and drives the breath through the left ; second, he inhales

through the left nostril, then compresses it, and inhales

through the other ; third, he stops the nose completely with thumb and forefinger, and holds his breath as long as

possible. All these acts must be done before sunrise, and

prepare for what is to follow.

Standing on the water's edge, he utters solemnly the famous syllable OM, pronouncing it

auin, with a length equalling that of three letters. It recalls to him the three persons of the Hindu trinity : Brahma, who creates ; Vishnu, who preserves ; Siva, who destroys. More noble than any other word, imperishable, says Manu, it is eternal as Brahma himself. It is not a sign, but a being,

a force ; a force which constrains the gods, superior to them,

the very essence of all things. Mysterious operations of the

mind, strange associations of ideas, from which spring

conceptions like these ! Having uttered this ancient and formidable syllable, the man calls by their names the three worlds : earth, air, sky ; and the four superior heavens. He

then turns towards the east, and repeats the verse ^ from the Rig-Veda : ' Let us meditate upon the resplendent glory of the divine vivifier, that it may enlighten our minds.' As he says the last words he takes water in the palm of his hand and pours it upon the top of his head. ' Waters,' he says,

' This is the famous Gayatri.

' give me strength and vigour that I may rejoice. Like loving mothers, bless us, penetrate us with your sacred essence. We come to wash ourselves from the pollution of sins : make us fruitful and prosperous.' Then follow other ablutions, other mantras, verses from the Rig-Veda, and this hymn, which relates the origin of all things : ' From the burning heat came out all things. Yes, the complete order of the world ; Night, the throbbing Ocean, and after the throbbing Ocean, Time, which separates Light from Darkness. All mortals are its subjects. It is this which disposes of all things, and has made, one after another, the sun, the sky, the earth, the intermediate air.' This hymn, says Manu, thrice repeated, effaces the gravest sins. " About this time, beyond the sands of the opposite shore of the Ganges, the sun appears. As soon as its brilliant disc becomes visible the multitude welcome it, and salute it with ' the offering of water.' This is thrown into the air, either from a vase or from the hand.

Thrice the worshipper,

standing in the river up to his waist, flings the water towards the sun. The farther and wider he flings it, the greater the virtue attributed to this act. Then the Brahman, seated

upon his heels, fulfils the most sacred of his religious duties :

he meditates upon his fingers. For the fingers are sacred, inhabited by different manifestations of Vishnu ; the thumb by Govinda, the index-finger by Madhava, the middle finger

by Hrikesa, the third by Trivikama and the little finger by Vishnu himself. ' Homage to the two thumbs,' says the Brahman, ' to the two index-fingers, to the two middle fingers, to the two " unnamed fingers," to the two little fingers, to the two palms, to the two backs of the hands.'

Then he touches the various parts of the body, and lastly, the right ear, the most sacred of all, where reside fire, water, the sun and the moon. He then takes a red bag (gomukhi), into which he plunges his hand, and by contortions of the fingers rapidly represents the chief incarnations of Vishnu : a fish, a tortoise, a wild boar, a lion, a slip-knot, a garland.^ " The second part of the service is no less rich than the first in ablutions and mantras. The Brahman invokes the ' It is not known how a slip-knot incarnation of Vishnu. For the incaina- and a garland are connected with any tions see articles Vaishnava sect.

n DAILY RITCAL 379

sun, * Mitra, who regards all creatures with unchani^infr

gaze/ and the Dawns, ' brilliant children of the sky,' the earliest divinities of our Aryan race. lie extols the world

of Brahma, that of Siva, that of Vishnu ; recites passages from the Mahabharata, the Puranas, all the first hymn of the

Rig-Veda, the first lines of the second, the first words of the

principal Vedas, of the Yajur, the Sama, and the Atharva,

then fragments of grammar, inspired prosodies, and, in conclusion, the first words of the book of the Laws of

Yajnavalkya, the philosophic Sutras : and finally ends the

ceremony with three kinds of ablutions, which are called the

refreshing of the gods, of the sages and of the ancestors.

" First, placing his sacred cord upon the left shoulder, the Brahman takes up water in the right hand, and lets it run off his extended fingers. To refresh the sages, the cord

must hang about the neck, and the water run over the side of the hand between the thumb and the forefinger, which is

bent back. For the ancestors, the cord passes over the

right shoulder, and the water falls from the hand in the same way as for the sages.

' Let the fathers be refreshed,' says the prayer, ' may this water serve all those who inhabit the seven worlds, as far as to Brahma's dwelling, even though their number be greater than thousands of millions of families. May this water, consecrated by my cord, be accepted by the men of my race who have left no sons.' " With this prayer the morning service ends. Now, remember that this worship is daily, that these formulas must be pronounced, these movements of the hands made with mechanical precision ; that if the worshipper forgets qne of the incarnations of Vishnu which he is to figure with his fingers, if he stop his left nostril when it should be the right, the entire ceremony loses its efficacy ; that, not to go astray amid this multitude of words and gestures required for each rite, he is obliged to use mnemotechnic methods ; that there are five of these for each series of formulas ; that his atten- tion always strained and always directed toward the externals of the cult, does not leave his mind a moment in which to reflect upon the profound meaning of some of these prayers, and you will comprehend the extraordinary scene that the banks of the Ganges at Benares present every morning

this anxious and demented multitude, these gestures, eager and yet methodical, this rapid movement of the lips, the fixed gaze of these men and women who, standing in the water, seem not even to see their neighbours, and count mentally like men in the delirium of a fever. Remember that there are ceremonies like these in the afternoon and also in the evening, and that in the intervals, in the street, in the house at meals, when going to bed, similar rites no less minute pursue the Brahman, all preceded by the exercises of respiration, the enunciation of the syllable OM, and the invocation of the principal gods.

It is estimated that between daybreak and noon he has scarcely an hour of rest from the performance of these rites. After the great powers of nature, the Ganges, the Dawn, and the Sun, he goes to worship in their temples the representations of divinity, the sacred trees, finally the cows, to whom he offers flowers. In his own dwelling other divinities await him, five black stones,^ representing Siva, Ganesa, Surya, Devi and Vishnu, arranged according to the cardinal points : one towards the north, a second to the south-east, a third to the south-west, a fourth to the north-west, and one in the centre, this order changing according as the worshipper regards one god or another as most important ; then there is a shell, a bell — to which, kneeling, he offers flowers—and, lastly, a vase, whose mouth contains Vishnu, the neck Rudra, the paunch Brahma, while at the bottom repose the three divine mothers, the Ganges, the Indus, and the Jumna.

" This is the daily cult of the Brahman of Benares, and on holidjiys it is still further complicated. Since the great epoch of Brahmanism it has remained the same. Some details may alter, but as a whole it has always been thus tyrannical and thus extravagant. As far back as the Upanishads appears the same faith in the power of articulate speech, the same imperative and innumerable prescriptions, the same singular formulas, the same enumeration of grotesque 1 In the Central Provinces Ganpati black stone or Saligram. Besides is represented by a round red stone, these every Brahman will have a special Surya by a rock crystal or the Swastik family god, who may be one of the sign, Devi by an image in brass or by above or another deity, as Rama or a stone brought from her famous temple Krishna, at Mahur, and Vishnu by the round

gestures. Every day, for more than twenty-five hundred years, since Buddhism was a protest a<^ainst the tyranny and absurdity of rites, has this race mechanically passed through this machinery, resulting in what mental malformations, what habitual attitudes of mind and will, the race is now too different from ourselves for us to be able to conceive." Secular Brahmans now, however, greatly abridge the length of their prayers, and an hour or an hour and a half in the morning suffices for the daily bath and purification, the worship of the household deities and the morning meal. Brahman boys are invested with the sacred thread 17- The between the ages of five and nine.

The ceremony is called thread Upanayana or the introduction to knowledge, since by it the

boy acquires the right to read the sacred books. Until this ceremony he is not really a Brahman, and is not bound to observe the caste rules and restrictions. By its performance he becomes Dvija or twice-born, and the highest importance is attached to the change or initiation. He may then begin

to acquire divine knowledge, and perhaps in past times it

was thought that he obtained the divine character belonging to a Brahman. The sacred thread is made of three strands

of cotton, which should be obtained from the cotton tree growing wild. Sometimes a tree is grown in the yard of

the house for the provision of the threads.

It has several knots in it, to which great importance is attached, the number of knots being different for a Brahman, a Kshatriya and a Vaishya, the three twice-born castes. The thread hangs from the left shoulder, falling on to the right hip. Some- times, when a man is married, he wears a double thread of six strands, the second being for his wife ; and after his father dies a treble one of nine strands. At the investiture the boy's nails are cut and his hair is shaved, and he per- forms the Jioni or fire sacrifice for the first time. He then acquires the status of a Brahmachari or disciple, and in former times he would proceed to some religious centre and begin to study the sacred books. The idea of this is pre- served by a symbolic ritual. Some Brahmans shave the boy's head completely, make a girdle of kusJia or inunj grass round his waist, provide him with a begging-bowl and tongs and the skin of an antelope to sit on and make him go and beg

from four houses. Among others the boy gets on to a wooden horse and announces his intention of going off to Benares to study. His mother then sits on the edge of a well and threatens to throw herself in if he will not change his mind, or the maternal uncle promises to give the boy his daughter in marriage. Then the boy relinquishes his inten- tion and agrees to stay at home. The sacred thread must always be passed through the hand before saying the Gayatri text in praise of the sun, the most sacred Brahmanical text. The sacred thread is changed once a year on the day of Rakshabandhan ; the Brahman and all his family change it together. The word Rakshabandhan means binding or tying up the devils, and it would thus appear that the sacred thread and the knots in it may have been originally intended to some extent to be a protection against evil spirits.

It is also changed on the occasion of a birth or death in the family, or of an eclipse, or if it breaks. The old threads are torn up or sewn into clothes by the very poor in the Maratha districts. It is said that the Brahmans are afraid that the Kunbis will get hold of their old threads, and if they do get one they will fold it into four strings, holding a lamp in the middle, and wave it over any one who is sick. The Brahmans think that if this is done all the accumulated virtue which they have obtained by many repe- titions of the Gayatri or sacred prayer will be transferred to the sick Kunbi.

Many castes now wear the sacred thread who have no proper claim to do so, especially those who have become landholders and aspire to the status of Rajputs. 18. Social The Brahman is of course supreme in Hindu society. position. y\q never bows his head in salutation to any one who is not a Brahman, and acknowledges with a benediction the greet- ings of all other classes. No member of another caste. Dr. Bhattacharya states, can, consistently with Hindu etiquette and religious beliefs, refuse altogether to bow to a Brahman. " The more orthodox Sudras carry their veneration for the priestly caste to such an extent that they will not cross the shadow of a Brahman, and it is not unusual for them to be under a vow not to eat any food in the morning before drinking Brahman nectar,^ or water in which the toe of a

1 Bipracharaiia»i7-ita.

Brfihrnan has been dipped. On the other hand, the pride of the Brahman is such that he does not bow even to the images of the gods in a Sudra's house. When a Brahman invites a Sudra the latter is usually asked to partake of the host's prasdda or favour in the shape of the leavings of his plate. Orthodox Sudras actually take offence if invited by the use of any other formula. No Sudra is allowed to cat in the same room or at the same time with Brahmans." ^ A man of low caste meeting a Brahman says ' Pailagi ' or * I fall at your feet,' and touches the Brahman's foot with his hand, which he then carries to his own forehead to signify this.

A man wishing to ask a favour in a humble manner stands on one leg and folds his cloth round his neck to show that his head is at his benefactor's disposal ; and he takes a piece of grass in his mouth by which he means to say, ' I am your cow.' Brahmans greeting each other clasp the hands and say ' Salaam,' this method of greeting being known as Namaskar. Since most Brahmans have abandoned the priestly calling and are engaged in Government service and the professions, this exaggerated display of reverence is tending to disappear, nor do the educated members of the caste set any great store by it, preferring the social estima-

tion attaching to such a prominent secular position as they

often attain for themselves. Any Brahman is, however, commonly addressed by other 19. Titles.

castes as Maharaj, great king, or else as Pandit, a learned man. I had a Brahman chuprassie, or orderly, who was regularly addressed by the rest of the household as Pandit, and on inquiring as to the literary attainments of this learned man, I found he had read the first two class-books in a primary school. Other titles of Brahmans are Dvija, or twice-born, that is, one who has had the thread ceremony performed ; Bipra, applied to a Brahman learned in the Shastras or scriptures ; and Srotriya, a learned Brahman who is engaged in the performance of Vedic rites. The Brahmans have a caste panchdyat, but among the 20. Caste educated classes the tendency is to drop the panchdyat pro- ^^^'l'^"'^ cedure and to refer matters of caste rules and etiquette to offences, the informal decision of a few of the most respected local ^ Hindu Castes and Sects, pp. 19-21. about food.

members.

In northern India there is no supreme authority for the caste, but the five southern divisions acknowledge the successor of the great reformer Shankar Acharya as their spiritual head, and important caste questions are referred to him. His headquarters are at the monastery of Sringeri on the Cauvery river in Mysore. Mr. Joshi gives four offences as punishable with permanent exclusion from caste : killing a Brahman, drinking prohibited wine or spirits, committing incest with a mother or step-mother or with the wife of one's spiritual preceptor, and stealing gold from a priest. Some very important offences, therefore, such as murder of any person other than a Brahman, adultery with a woman of impure caste and taking food from her, and all offences against property, except those mentioned, do not involve permanent expulsion.

Temporary exclusion is inflicted for a variety of offences, among which are teaching the Vedas for hire, receiving gifts from a Sudra for performing fire- worship, falsely accusing a spiritual preceptor, subsisting by the harlotry of a wife, and defiling a damsel. It is possible that some of the offences against morality are compara- tively recent additions. Brahmans who cross the sea to be educated in England are readmitted into caste on going through various rites of purification ; the principal of these is to swallow the five products of the sacred cow, milk, ghi or preserved butter, curds, dung and urine.