Dhobi: Central Provinces Of India

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in<br/>1916 its contents related only t...") |

(→Dhobi, Warthi, Baretha, Chakla, Rajak, Parit) |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

==Dhobi, Warthi, Baretha, Chakla, Rajak, Parit== | ==Dhobi, Warthi, Baretha, Chakla, Rajak, Parit== | ||

| − | + | The professional caste of washermen. The name is derived structure from the Hindi dhotta, and the Sanskrit dhav, to wash, of the Warthi is the Maratha name for the caste, and Bareth or Baretha is an honorific or compHmentary term of address. | |

Rajak and Parit are synonyms, the latter being used in the Maratha Districts. The Chakla caste of Madras are leather- workers, but in Chanda a community of persons is found who are known as Chakla and are professional washermen. In 191 1 the Dhobis numbered 165,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berar, or one to every hundred inhabitants. They are numerous in the Districts with large towns and also in Chhattlsgarh, where, like the Dhobas of Bengal, | Rajak and Parit are synonyms, the latter being used in the Maratha Districts. The Chakla caste of Madras are leather- workers, but in Chanda a community of persons is found who are known as Chakla and are professional washermen. In 191 1 the Dhobis numbered 165,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berar, or one to every hundred inhabitants. They are numerous in the Districts with large towns and also in Chhattlsgarh, where, like the Dhobas of Bengal, | ||

they have to a considerable extent abandoned their hereditary profession and taken to cultivation and other callings. No | they have to a considerable extent abandoned their hereditary profession and taken to cultivation and other callings. No | ||

| Line 180: | Line 180: | ||

returned carefully repaired." | returned carefully repaired." | ||

^ | ^ | ||

| + | |||

==Dhuri== | ==Dhuri== | ||

A caste belonging exclusively to Chhattlsgarh, i. Origin which numbered 3000 persons in 191 i. Dhuri is an honorific abbreviation from Dhuriya as Bani from Bania. | A caste belonging exclusively to Chhattlsgarh, i. Origin which numbered 3000 persons in 191 i. Dhuri is an honorific abbreviation from Dhuriya as Bani from Bania. | ||

Revision as of 21:09, 11 February 2014

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Dhobi

LIST OF PARAGRAPHS 1. Character a7ni structure of the 5. Occupation : %vashing clothes. caste. 6. Social position. 2. Marriage customs. 7. Proverbs about the Dhobi. 3. Other social customs. 8. lVeari??g and leiulitig the clothes 4. Religion. of customers.

Dhobi, Warthi, Baretha, Chakla, Rajak, Parit

The professional caste of washermen. The name is derived structure from the Hindi dhotta, and the Sanskrit dhav, to wash, of the Warthi is the Maratha name for the caste, and Bareth or Baretha is an honorific or compHmentary term of address. Rajak and Parit are synonyms, the latter being used in the Maratha Districts. The Chakla caste of Madras are leather- workers, but in Chanda a community of persons is found who are known as Chakla and are professional washermen. In 191 1 the Dhobis numbered 165,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berar, or one to every hundred inhabitants. They are numerous in the Districts with large towns and also in Chhattlsgarh, where, like the Dhobas of Bengal, they have to a considerable extent abandoned their hereditary profession and taken to cultivation and other callings. No account worth reproduction has been obtained of the origin of the caste.

In the Central Provinces it is purely functional, as is shown by its subdivisions ; these are generally of a territorial nature, and indicate that the Dhobis like the other professional castes have come here from all parts of the country. Instances of the subcastes are : Baonia and Beraria from Berar ; Malwi, Bundelkhandi, Nimaria, Kanaujia, Udaipuria from Udaipur ; Madrasi, Dharampuria from Dharampur, and so on. A separate subcaste is formed of

Muhammadan Dhobis. The exogamous groups known as khcro are of the usual low-caste type, taking their names

from villages or titular or professional terms.

Marriage within the kJicro is prohibited and also the union of first cousins. It is considered disgraceful to accept a price for a bride, and it is said that this is not done even by the parents of poor girls, but the caste will in such cases raise a subscription to defray the expenses of her marriage. In the northern Districts the marriages of Dhobis are characterised by continuous singing and dancing at the houses of the bridegroom and bride, these performances being known as sajnai and birha. Some man also puts on a long coat, tight down to the waist and loose round the hips, to have the appearance of a dancing-girl, and dances before the party, while two or three other men play. Mr. Crooke considers that this ritual, which is found also among other low castes, resembles the European custom of the False Bride and is intended to divert the evil eye from the real bride.

He writes:^ "Now there are numerous customs which have been grouped in Europe under the name of the False Bride. Thus among the Esthonians the false bride is enacted by the bride's brother dressed in woman's clothes ; in Polonia by a bearded man called the Wilde Braut ; in Poland by an old woman veiled in white and lame ; again among the Esthonians by an old woman with a brickwork crown ; in Brittany, where the substitutes are first a little girl, then

the mistress of the house, and lastly the grandmother. " The supposition may then be hazarded in the light of the Indian examples that some one assumes on this

occasion the part of the bride in order to divert on himself from her the envious glance of the evil eye." Any further

information on this interesting custom would be welcome.

The remarriage of widows is allowed, and in Betul the

bridegroom goes to the widow's house on a dark night wrapped up in a black blanket, and presents the widow with new clothes and bangles, and spangles and red lead for the

forehead. Divorce is permitted with the approval of the caste headman by the execution of a deed on stamped

paper.

1 Folklore of Northern India, vol. ii. p. 8.

After a birth the mother is allowed no food for some 3. Other days except country sugar and dates. The child is given c°s[on^<; some honey and castor-oil for the first two days and is then allowed to suckle the mother. A i^it is dug inside the lying-in room, and in this arc deposited water and the first cuttings of the nails and hair of the child. It is filled up and on her recovery the mother bows before it, praying for similar safe deliveries in future and for the immunity of the child from physical ailments. After the birth of a male child the mother is impure for seven days and for five days after that of a female. The principal deity of the Dhobis is Ghatoia, the god of 4. Rdi- the ghat or landing-place on the river to which they go to ^'°"" wash their clothes. Libations of liquor are made to him in the month of Asarh (June), when the rains break and the rivers begin to be flooded. Before entering the water to wash the clothes they bow to the stone on which these are beaten out, asking that their work may be quickly finished ; and they also pray to the river deity to protect them from snakes and crocodiles.

They worship the stone on the Dasahra festival, making an offering to it of flowers, turmeric and cooked food. The Dhobi's washing-stone is believed to be haunted by the ghosts of departed Dhobis when revisiting the glimpses of the moon, and is held to have magical powers. If a man requires a love-charm he should steal a supdri or areca-nut from the bazar at night or on the occasion of an eclipse. The same night he goes to the Dhobi's stone and sets the nut upon it. He breaks an &gg and a cocoanut over the stone and burns incense before it. Then he takes the nut away and gives it to the woman of his fancy, wrapped up in betel-leaf, and she will love him. Their chief festivals are the Holi and Diwali, at which they drink a great deal. The dead are buried or burnt as may be convenient, and mourning is observed for three days only, the family being purified on the Sunday or Wednesday following the death. They have a caste committee whose president is known as Mehtar, while other ofificials are the Chaudhri or vice-president, and the Badkur, who appoints dates for the penal feasts and issues the summons to the caste-fellows. These posts are hereditary and their holders

receive presents of a rupee and a cloth when members of the caste have to give expiatory feasts. Before washing his clothes the Dhobi steams them/ hanging them in a bundle for a time over a cauldron of boiling water. After this he takes them to a stream or pond and washes them roughly with fuller's earth. The washerman steps nearly knee-deep into the water, and taking a quantity of clothes by one end in his two hands he raises them aloft in the air and brings them down heavily upon a huge stone slab, grooved, at his feet.

This threshing opera-

tion he repeats until his clothes are perfectly clean. In

Saugor the clothes are rubbed with wood-ashes at night and

beaten out in water with a stick in the morning. Silk

clothes are washed with the nut of the rltha tree {Sapijidus

eniarginatus) which gives a lather like soap. Sir H. Risley writes of the Dacca washermen : ^ " For washing muslins

and other coloured garments well or spring water is alone used ; but if the articles are the property of a poor man or

are commonplace, the water of the nearest tank or river is

accounted sufficiently good. Indigo is in as general use as

in England for removing the yellowish tinge and whitening the material.

The water of the wells and springs bordering

on the red laterite formation on the north of the city has

been for centuries celebrated, and the old bleaching fields of

the European factories were all situated in this neighbour-

hood. Various plants are used by the Dhobis to clarify

water such as the nirniali {Strychnos potatoricvi), the piu

{Basella), the Jidgphani {Cactus indicus) and several plants of the mallow family. Alum, though not much valued, is some-

times used." In most Districts of the Central Provinces the

Dhobi is employed as a village servant and is paid by annual

contributions of grain from the cultivators. For ordinary washing he gets half as much as the blacksmith or carpenter,

or I 3 to 2 lbs. of grain annually from each householder, with about another lo lbs, at seedtime or harvest. When he brings the clothes home he also receives a meal or a

ckapdtiy and well-to-do persons give him their old clothes

as a present. In return for this he washes all the clothes of

the family two or three times a month, except the loin-cloths

' Sherring's Hindu Castes, i. 342-3. ^ Tribes and Castes, art. Dhobi.

and women's bodices which they themselves wash daily. The Dhobi is also employed on the occasion of a birth or a death. These events cause impurity and hence all the clothes of all the members of the family must be washed when the impurity ceases. In Saugor when a man dies the Dhobi receives eight annas and for a woman four annas, and similar rates in the case of the birth of a male or female child.

When the first son is born in a family the Dhobi and barber place a

brass vessel on the top of a pole and tie a Hag to it as a

cloth and take it round to all the friends and relations of the family, announcing the event. They receive presents of grain and money which they expend on a drinking-bout. The Dhobi is considered to be impure, and he is not 6. Social allowed to come into the houses of the better castes nor to p°^'^'°"- touch their water-vessels. In Saugor he may come as far

as the veranda but not into the house. His status would

in any case be low as a village menial, but he is speci-

ally degraded, Mr. Crooke states, by his task of washing the clothes of women after child-birth and his consequent'

association with puerperal blood, which is particularly ab- horred. Formerly a Brahman did not let the Dhobi wash

his clothes, or, if he did, they were again steeped in water in the house as a means of purification.

Now he contents him-

self with sprinkling the clean clothes with water in which a piece of gold has been dipped. The Dhobi is not so impure as the Chamar and Basor, and if a member of the higher castes touches him inadvertently it is considered sufficient to wash the face and hands only and not the clothes. Colonel Tod writes^ that in Rajputana the washermen's wells dug at the sides of streams are deemed the most impure of all receptacles. And one of the most binding oaths is that a man as he swears should drop a pebble into one of these wells, saying, " If I break this oath may all the good deeds of my forefathers fall into the washerman's well like this pebble." Nevertheless the Dhobi refuses to wash the clothes of some of the lowest castes as the Mang, Mahar and Chamar. Like the Teli the Dhobi is unlucky, and it is a bad omen to see him when starting on a journey or going out in the morning. But among some of the

^ Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan.

higher castes on the occasion of a marriage the elder members of the bridegroom's family go with the bride to the Dhobi's house. His wife presents the bride with betel- leaf and in return is given clothes with a rupee.

This cere- mony is called sohdg or good fortune, and the present from the Dhobin is supposed to be lucky. In Berar the Dhobi is also a Balutedar or village servant. Mr. Kitts writes of him : ^ " At a wedding he is called upon to spread the clothes on which the bridegroom and his party alight

on coming to the bride's house ; he also provides the cloth on which the bride and bridegroom are to sit and fastens the kankan (bracelet) on the girl's hand. In the Yeotmal Dis- trict the barber and the washerman sometimes take the place of the maternal uncle in \he j'kenda dance ; and when the bridegroom, assisted by five married women, has thrown the necklace of black beads round the bride's neck and has tied it with five knots, the barber and the washerman advance, and lifting the young couple on their thighs dance to the music of the wdjantri, while the bystanders besprinkle them

with red powder." In Chhattlsgarh the Dhobis appear to have partly aban- doned their hereditary profession and taken to agriculture and other callings. Sir Benjamin Robertson writes of them : ^ " The caste largely preponderates in Chhattlsgarh, a part of the country where, at least to the superficial observer, it would hardly seem as if its services were much availed of; the number of Dhobis in Raipur and Bilaspur is nearly 40,000. In both Districts the washerman is one of the recognised village servants, but as a rule he gets no fixed payment,

and the great body of cultivators dispense with his services altogether.

According to the Raipur Settlement Report (Mr, Hewett), he is employed by the ryots only to wash the clothes of the dead, and he is never found among a popula- tion of Satnamis. It may therefore be assumed that in

Chhattlsgarh the Bareth caste has largely taken to cultiva- tion." In Bengal Sir H. Risley states^ that "the Dhobi often gives up his caste trade and follows the profession of a writer, messenger or collector of rent {tahsilddr), and it is

1 Berdr Census Report (1881), p. 155. 2 Central Provinces Census Report {1S91), p. 202. ^ Loc. cit.

an old native tradition that a licn^^ali Dhobi was the first interpreter the English factory at Calcutta had, while it is further stated that our early commercial transactions were carried on solely through the agency of low-caste natives. The Dhobi, however, will never engage himself as an indoor servant in the house of a European." Like the other castes who supply the primary needs 7. Pro- of the people, the Dhobi is not regarded with much favour ^^^^^l^ t^e by his customers, and they revenge themselves in various Dhobi. sarcasms at his expense for the injury caused to their clothes by his drastic measures. The following are mentioned by Sir G. Grierson : ^ ' Dhobi par Dhobi base, tab kapre par sdbun pare', or ' When many Dhobis compete, then some soap gets to the clothes,' and ' It is only the clothes of the Dhobi's father that never get torn.

The Dhobi's donkey is a familiar sight as one meets him on the road still toiling as in the time of Issachar between two bundles of clothes each larger than -himself, and he has also become proverbial, ' Dhobi ka gadJia neh ghar ka neh ghat ka^ ' The Dhobi's donkey is always on the move ' ; and ' The ass has only one master (a washerman), and the washerman has only one steed (an ass).' The resentment felt for the Dhobi by his customers is not confined to his Indian clients, as may be seen from Eha's excellent description of the Dhobi in BeJiind the Bimgalozv ; and it may perhaps be permissible to intro- duce here the following short excerpt, though it necessarily loses in force by being detached from the context : " Day after day he has stood before that great black stone and wreaked his rage upon shirt and trouser and coat, and coat and trouser and shirt.

Then he has wrung them as if he were wringing the necks of poultry, and fixed them on his drying line with thorns and spikes, and finally he has taken the battered garments to his torture chamber and ploughed them with his iron, longwise and crosswise and slantwise, and dropped glowing cinders on their tenderest places. Son has followed father through countless generations in cultivating this passion for destruction, until it has become the monstrous growth which we see and shudder at in the Dhobi." 1 Bihar Peasant Life, s.v. Dhobi.

It is also currently believed that the Dhobi wears the clothes of his customers himself. Thus, ' The Dhobi looks smart in other people's clothes ' ; and ' Rdjdche shiri, Paritdche tiri,' or ' The king's headscarf is the washer- man's loin-cloth.' On this point Mr. Thurston writes of the Madras washerman : " It is an unpleasant reflection that the Vannans or washermen add to their income by hiring out the clothes of their customers for funeral parties, who lay them on the path before the pall-bearers, so that they may not step upon the ground. On one occasion a party of Europeans, when out shooting near the village of a hill tribe, met a funeral procession on its way to the burial-ground. The bier was draped in many folds of clean cloth, which one of the party recognised by the initials as one of his bed-sheets. Another identified as his sheet the cloth on which the corpse was lying. He cut off the corner with the initial, and a few days later the sheet was returned by the Dhobi, who pretended ignorance of the mutilation, and gave as an explanation that it must have been done in his absence by one of his assistants.

And Eha describes the same custom in the following amusing manner : " Did you ever open your handkerchief with the suspicion that you had got a duster into your pocket by mistake, till the name of De Souza blazoned on the corner showed you that you were wearing some one else's property ? An accident of this kind reveals a beneficent branch of the Dhobi's business, one in which he comes to the relief of needy respectability. Suppose yourself (if you can) to be Mr. Lobo, enjoying the position of first violinist in a string band which performs at Parsi weddings and on other festive occasions. Noblesse oblige ; you cannot evade the necessity for clean shirt-fronts, ill able as your precarious income may be to meet it. In these circumstances a Dhobi with good con- nections is what you require.

He finds you in shirts of the best quality at so much an evening, and you are saved all risk and outlay of capital ; you need keep no clothes except a greenish-black surtout and pants and an effective necktie. In this way the wealth of the rich helps the want of the poor without their feeling it or knowing it—an excellent arrange-

^ Ethnographic Notes in Soutliem India, p. 226.

and sub-

divisions.

ment. Sometimes, unfortunately, Mr. Lobo has a few clothes of his own, and then, as I have hinted, the Dhobi may ex- change them by mistake, for he is uneducated and has much to remember ; but if you occasionally suffer in this way ycm gain in another, for Mr. Lobo's family arc skilful with the needle, and I have sent a torn garment to the wash which returned carefully repaired." ^

Dhuri

A caste belonging exclusively to Chhattlsgarh, i. Origin which numbered 3000 persons in 191 i. Dhuri is an honorific abbreviation from Dhuriya as Bani from Bania.

The special occupation of the caste is rice-parching, and they are an off- shoot from Kahars, though in Chhattisgarh the Dhuris now consider the Kahars as a subcaste of their own. In Bengal the Dhuriyas are a subcaste of the Kandus or Bharbhiinjas. Sir H. Risley states that " the Dhurias rank lowest of all the subcastes of Kandus, owing either to their having taken up the comparatively menial profession of palanquin-bearing, or to their being a branch of the Kahar caste who went in for grain-parching and thus came to be associated with the Kandus." ^ The caste have immigrated to Chhattlsgarh from the United Provinces. In Kawardha they believe that the Raja of that State brought them back with him on his return from a pilgrimage.

In Bilaspur and Raipur they say they came from Badhar, a pargana in the Mirzapur District, adjoining Rewah. Badhar is mentioned in one of the Rajim inscriptions, and is a place remembered by other castes of Chhattlsgarh as their ancestral home. The Dhuris of Chhattlsgarh relate their origin as follows : Mahadeo went once to the jungle' and the damp earth stuck to his feet. He scraped it off and made it into a man, and asked him what caste he would like to belong to. The man said he would leave it to Mahadeo, who decided that he should be called Dhuri from d/u'ir, dust. The man then asked Mahadeo to assign him an occupation, and Mahadeo said that as he was made from dust, which is pounded earth, his work should

1 Behind the Bungalow. Lai Misra, a clerk in the Gazetteer 2 This article is mainly compiled office, from papers by Mr. Gokul Prasad, ^ Tribes and Castes of Bengal, art. Naib-Tahsildar, Dhamtari, and Pyare Kandu.

be to prepare cJieora or pounded rice, and added as a special distinction that all castes including Brahmans should eat the pounded rice prepared by him.

All castes do eat cheora because it is not boiled with water. The Dhuris have two subcastes, a higher and a lower, but they are known by different names in different tracts. In Kawardha they are

called Raj Dhuri and Cheorakuta, the Raj Dhuris being

the descendants of personal servants in the Raja's family

and ranking above the Cheorakutas or rice-pounders. In

Bilaspur they are called Badharia and Khawas, and in Raipur Badharia and Desha. The Khawas and Desha

subcastes do menial household service and rank below the Badharias, who are perhaps later immigrants and refuse to engage in this occupation. The names of their exogamous sections are nearly all territorial, as Naugahia from Naogaon

in Bilaspur District, Agoria from Agori, a pargana in Mirza- pur District, Kashi or Benares, and a number of other names

derived from villages in Bilaspur.

But the caste do not strictly enforce the rule forbidding marriage within the gotra or section, and are content with avoiding three generations both on the father's and mother's side. They have probably been driven to modify the rule on account of the paucity of their numbers and the difficulty of arranging marriages. For the same reason perhaps they look with indulgence on the practice, as a rule strictly prohibited, of marriage with a woman of another caste of lower social rank, and will admit the children of such a marriage into the caste, though not the woman herself Infant-marriage is in vogue, and polygamy is permitted only if the first wife be barren. The betrothal is cemented by an exchange of betel-leaves and areca-nuts between the fathers of the engaged couple. A bride-price of from ten to twenty rupees is usually paid. Some rice, a pice coin, 2 I cowries and 2 1 pieces of turmeric are placed in the hole in which the marriage post is erected. When the wedding procession arrives at the girl's house the bridegroom goes to the marriage -shed and pulls out the festoons of mango leaves, the bride's family trying to prevent him by offering him a winnowing-fan. He then approaches the door of the house, behind which his future mother-in-law is standing,

and slips a piece of cloth through the door for her. She takes this and retires without bcint^ seen.

The wedding consists of the bhdrnvar ceremony or walkin<^ round the sacred pole. During the proceedings the women tie a new

thread round the bridegroom's neck to avert the evil eye.

After the wedding the bride and bridegroom, in opposition to the usual custom, must return to the latter's house on

foot. In explanation of this they tell a story to the effect

that the married couple were formerly carried in a palanquin. But on one occasion when a wedding procession came to

a river, everybody began to catch fish, leaving the bride

deserted, and the palanquin-bearers, seeing this, carried her off.

To prevent the recurrence of such a mischance the couple now have to walk. Widow-marriage is permitted, and the widow usually marries her late husband's younger brother. Divorce is only permitted for misconduct on the part of the wife. The Dhuris principally worship the goddess Devi. 3- Reii- Nearly all members of the caste belong to the Kablrpanthi fdiefs. sect. They believe that the sun on setting goes through the earth, and that the milky way is the path by which the elephant of the heavens passes from south to north to feed on the young bamboo shoots, of which he is ver}' fond. They think that the constellation of the Great Bear is a cot with three thieves tied to it. The thieves came to steal the cot, which belonged to an old woman, but God caught them and tied them down there for ever. Orion is the plough left by one of the Pandava brothers after he had finished tilling the heavens.

The dead are burnt. They observe mourning during nine or ten days for an adult and make libations to the dead at the usual period in the month of Kunwar (September-October). The proper occupation of the caste is to parch rice. 4- Occupa- The rice is husked and then parched in an earthen pan, s°(!iai"'^ and subsequently bruised with a mallet in a wooden mortar, status. When prepared in this manner it is called cheora. The Dhuris also act as kJiidmatgdrs or household servants, but the members of the Badharia subcaste refuse to do this work. Some members of the caste are fishermen, and others grow melons and sweet potatoes. Considering that they VOL. II 2 M

live in Chhattisgarh, the caste are somewhat scrupulous in the matter of food, neither eating fowls nor drinking liquor. The Kawardha Dhuris, however, who are later immigrants than the others, do not observe these restrictions, the reason for which may be that the Dhuris think it necessary to be strict in the matter of food, so that no one may object to take parched rice from them. Rawats and Gonds take food from their hands in some places, and their social status in Chhattisgarh is about equivalent to that of the Rawats or Ahirs. A man of the caste who kills a cow or gets vermin in a wound must go to Amarkantak to bathe in the Nerbudda. 2. Sub- divisions.

Dumal

An agricultural caste found in the Uriya country and principally in the Sonpur State, recently trans- ferred to Bihar and Orissa. In 1901, 41,000 Dumals were enumerated in the Central Provinces, but only a few persons now remain. The caste originally came from Orissa. They themselves say that they were formerly a branch of the Gaurs, with whom they now have no special connection. They derive their name from a village called Dumba Hadap in the Athmalik State, where they say that they lived. Another story is that Dumal is derived from Duma, the name of a gateway in Baud town, near which they dwelt. Sir H. Risley says : " The Dumals or Jadupuria Gaura seem to be a group of local formation. They cherish the tradition that their ancestors came to Orissa from Jadupur, but this appears to be nothing more than the name of the Jadavas or Yadavas, the mythical progenitors of the Goala caste transformed into the name of an imaginary town." The Dumals have no subcastes, but they have a com- plicated system of exogamy.

This includes three kinds of divisions or sections, the got or sept, the barga or family title and the initti or earth from which they sprang, that is, the name of the original village of the clan. Marriage is prohibited only between persons who have the same got, barga and viitti ; if any one of these is different it is allowed. Thus a man of the Nag got, Padhan barga and Hindolsai initti may marry a girl of the Nag got, Padhan barga and ^ This article is taken almost entirely from a paper drawn up by Mr. HIra Lai, Extra Assistant Commissioner. SUBDIVISIONS 53' Kandhpadfi mitli\ or one of the Nag ^^/, K.irmi harga and Hindolsai ;////// ; or one of tlie Bud got, Padhan barga and llindolsai ;//////. The btDgas arc very numerous, but the gots and viittis are few and common to many bargas ; and many people have forgotten the name of their initti altogether. Marriage therefore usually depends on the bargas being different. The following table shows the got, barga and Diitti of a few families : Got.

before taking to their present occupation of agriculture were temple servants, household menials and cattle -herds, thus fulfilling the functions now performed by the Rawat or Gaur caste of graziers in Sambalpur. The names of the mittis or villages show that their original home was in the Orissa Tributary Mahals, while the totemistic names of gots indicate their Dravidian origin.

The marriage of first

cousins is prohibited.

3. Mar- Girls must be married before adolescence, and in the "age. event of the parents failing to accomplish this, the following

heavy penalty is imposed on the girl herself She is taken

to the forest and tied to a tree with thread, this proceeding signifying her permanent exclusion from the caste. Any one belonging to another caste can then take her away and

marry her if he chooses to do so. In practice, however, this

penalty is very rarely imposed, as the parents can get out

of it by marrying her to an old man, whether he is already

married or not, the parents bearing all the expenses, while

the husband gives two to four annas as a nominal con- tribution.

After the marriage the old man can either keep the girl as his wife or divorce her for a further nominal pay- ment of eight annas to a rupee. She then becomes a widow and can marry again, while her parents will get ten or twenty rupees for her. The boy's father makes the proposal for the marriage according to the following curious formula. Taking some fried grain he goes to the house of the father of the bride and addresses him . as follows in the presence of the neigh- bours and the relatives of both parties : " I hear that the tree has budded and a blossom has come out ; I intend to pluck it." To which the girl's father replies : " The flower is delicate ; it is in the midst of an ocean and very difficult to approach : how will you pluck it ? " To which the reply is : 'I shall bring ships and dongas (boats) and ply them in the ocean and fetch the flower.' And again : " If you do pluck it, can you support it ? Many difficulties may stand in the way, and the flower may wither or get lost ; will it be possible for you to steer the flower's boat in the ocean of time, as long as it is destined to be in this v/orld ? " To which the answer is : ' Yes, I shall, and it is with that

intention that I have come to you.' On which the girl's father finally says : ' Very well then, I have given you the flower.' The question of the bride's price is then discussed.

There are three recognised scales—Rs. 7 and 7 pieces of cloth, Rs. 9 and 9 pieces of cloth, and Rs. i 8 and i 8 pieces of cloth. The rupees in question are those of Orissa, and each of them is worth only two-thirds of a Government

rupee. In cases of extreme poverty Rs. 2 and 2 pieces of cloth are accepted. The price being fixed, the boy's father

goes to pay it after an interval ; and on this occasion he

holds out his cloth, and a cocoanut is placed on it and

broken by the girl's father, which confirms the betrothal.

Before the marriage seven married girls go out and dig

earth after worshipping the ground, and on their return

let it all fall on to the head of the bridegroom's mother, which is protected only by a cloth.

On the next day offerings are made to the ancestors, who are invited to attend the ceremony as village gods. The bridegroom is shaved clean and bathed, and the Brahman then ties an iron ring to his wrist, and the barber puts the turban and marriage- crown on his head. The procession then starts, but any barber who meets it on the way may put a fresh marriage- crown on the bridegroom's head and receive eight annas or a rupee for it, so that he sometimes arrives at his destination wearing four or five of them. The usual ceremonies attend the arrival. At the marriage the couple are blindfolded and seated in the shed, while the Brahman priest repeats mantras or verses, and during this time the parents and the parties must continue placing nuts and pice all over the shed. These are the perquisites of the Brahman.

The hands of the couple are then tied together with kusha grass {Eragrostis cynosu- roides), and water is poured over them. After the ceremony the couple gamble with seven cowries and seven pieces of turmeric. The boy then presses a cowrie on the ground with his little finger, and the girl has to take it away, which she easily does. The girl in her turn holds a cowrie inside her clenched hand, and the boy has to remove it with his little finger, which he finds it impossible to do. Thus the boy always loses and has to promise the girl something, either to give her an ornament or to take her on a pilgrimage, or to 534 DUMAL part make her the mistress of his house. On the fifth or last day of the ceremony some curds are placed in a small pot, and the couple are made to churn them ; this is probably symbolical of the caste's original occupation of tending cattle.

The bride goes to her husband's house for three days, and then returns home. When she is to be finally brought to her husband's house, his father with some relatives goes to the parents of the girl and asks for her. It is now strict etiquette for her father to refuse to send her on the first occasion, and they usually have to call on him three or four times at intervals of some days, and selecting the days given by the astrologer as auspicious. Occasionally they have to go as many as ten times ; but finally, if the girl's father proves very troublesome, they send an old woman who drags away the girl by force. If the father sends her away willingly he gives her presents of several basket-loads of grain, oil, turmeric, cooking-pots, cloth, and if he is well off a cow and bullocks, the value of the presents amounting to about Rs. 50.

The girl's brother takes her to her husband's house, where a repetition of the marriage ceremony on a small scale is performed. Twice again after the consummation of the marriage she visits her parents for periods of one and six months, but after this she never again goes to their house unaccompanied by her husband. Widow-marriage is allowed, and the widow may marry the younger brother of her late husband or not as she pleases. But if she marries another man he must pay a sum of Rs. 10 to Rs. 20 for her, of which Rs. 5 go to the Panua or headman of the caste, and Rs. 2 to their tutelary goddess Parmeshwari. The children by the first husband are kept either by his relatives or the widow's parents, and do not go to the new husband. When a bachelor marries a widow, he is first married to a flower or Sahara tree. A widow who has remarried cannot take part in any worship or marriage ceremony in her house, not even in the marriage of her own sons. Divorce is allowed, and is effected in the presence of the caste panchdyat or committee. A divorced woman may marr}^ again.

The caste worship the goddess Parmeshwari, the wife of Vishnu, and Jagannath, the Uriya incarnation of Vishnu. Parmeshwari is worshipped by Brahmans, who offer bread

and klilr or rice and milk- to her ; goats are also offered by the Dehri or Mahakul, the caste priest, who receives the heads of the goats as his remuneration. They believe in witches, who they think drink the blood of children, and employ sorcerers to exorcise them. They worship a stick on Dasahra day in remembrance of their old profession of herding cattle, and they worship cows and buffaloes at the full moon of Shrawan (July-August). During Kunwar, on the eighth day of each fortnight, two festivals are held. At the first each girl in the family wears a thread containing eighteen knots twisted three times round her neck.

All the girls fast and receive presents of cloths and grain from their brothers. This is called Bhaijiuntia, or the ceremony for the welfare of the brothers. On the second day the mother of the family does the same, and receives presents from her sons, this being Puajiuntia, or the ceremony for the welfare of sons. The Dumals believe that in the beginning water covered the earth. They think that the sun and moon are the eyes of God, and that the stars are the souls of virtuous men, who enjoy felicity in heaven for the period measured by the sum of their virtuous actions, and when this has expired have to descend again to earth to suffer the agonies of human life. When a shooting star is seen they think it is the soul of one of these descending to be born again on earth.

They both burn and bury their dead according to their means. After a body is buried they make a fire over the grave and place an empty pot on it. Mourning is observed for twelve days in the case of a married and for seven in the case of an unmarried person. Children dying when less than six days old are not mourned at all. During mourning the persons of the household do not cook for themselves. On the third day after the death three leaf- plates, each containing a little rice, sugar and butter, are offered to the spirit of the deceased. On the fourth day four such plates are offered, and on the fifth day five, and so on up to the ninth day when the Pindas or sacrificial cakes are offered, and nine persons belonging to the caste are invited, food and a new piece of cloth being given to each. Should only one attend, nine plates of food would be served to him, and he would be given nine pieces of

cloth. If two or more persons in a family are killed by a tiger, a Sulia or magician is called in, and he pretends to be the tiger and to bite some one in the family, who is then carried as a corpse to the burial-place, buried for a short time and taken out again.

the ceremonies of mourning

are observed for him' for one day. This proceeding is be- lieved to secure immunity for the family from further attacks.

In return for his services the Sulia gets a share of every- thing in the house corresponding to what he would receive, supposing he were a member of the family, on a partition.

Thus if the family consisted of only two persons he would get a third part of the whole property. The Dumals eat meat, including wild boar's flesh, but not beef, fowls or tame pigs. They do not drink liquor. They will take food cooked with water from Brahmans and Sudhs, and even the leavings of food from Brahmans.

This is probably because they were formerly the household servants of Brahmans, though they have now risen some- what in position and rank, together with the Koltas and Sudhs, as a good cultivating caste.

Their women and girls

can easily be distinguished, the girls because the hair is shaved until they are married, and the women because they wear bangles of glass on one arm and of lac on the other. They never wear nose-rings or the ornament called pairi on the feet, and no ornaments are worn on the arm above the elbow. They do not wear black clothing. The women

are tattooed on the hands, feet and breast. Morality within the caste is lax. A woman going wrong with a man of her own caste is not punished, because the Dumals live generally in Native States, where it is the business of the Raja to find the seducer. But she is permanently excom- municated for a liaison with a man of another caste.

Eating with a very low caste is almost the only offence which entails permanent exclusion for both sexes. The Dumals have a bad reputation for fidelity, according to a saying : 'You cannot call the jungle a plain, and you should not call the Dumal a brother,' that is, do not trust a Dumal. Like the Ahirs they are somewhat stupid, and when enquiry was being made from them as to what crops they did not grow, one of them replied that they did not sow salt. They are

good cultivators, and will grow anything except hemp and turmeric. In some places they still follow their traditional occupation of grazing cattle.

Fakir

The class of Muhanimadan beggars. In the i. Gencmi Central Provinces the name is practically confined to "° "^^' Muhammadans, but in Upper India Hindus also use it. Nearly 9000 Fakirs were returned in 191 1, being residents mainly of Districts with large towns, as Jubbulpore, Nagpur and Amraoti. Nearly two-fifths of the Muhammadans of the Central Provinces live in towns, and Muhammadan beggars would naturally congregate there also.

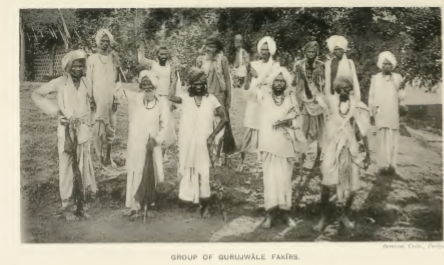

The name is derived from the Arabic fakr, poverty. The Fakirs are often known as Shah, Lord, or Sain, a corruption of the Sanskrit Swami, master, Muhammad did not recognise religious ascetism, and expressly discouraged it. But even during his lifetime his companions Abu Bakr and Ali estab- lished religious orders with Zikrs or special exercises, and all Muhammadan Fakirs trace their origin to Abu Bakr or Ali subsequently the first and fourth Caliphs.- The Fakirs are divided into two classes, the Ba Shara or those who live according to the rules of Islam and marry ; and the Be Shara or those without the law. These latter have no wives or homes ; they drink intoxicating liquor, and neither fast, pray nor rule their passions. But several of the orders contain both married and celibate groups. The principal classes of Fakirs in the Central Provinces 2. Prin- are the Madari, Gurujwale or Rafai, Jalali, Mewati, Sada or^^gj-s. Sohagal and Nakshbandia. All of these except the Nakshbandia are nominally at least Be Shara, or without the law, and celibate.

The Madari are the followers of one Madar Shah, a converted Jew of Aleppo, whose tomb is supposed to be at Makhanpur in the United Provinces. Their characteristic badge is a pair of pincers. Some, in order to force people to give them alms, go about dragging a chain or lashing their legs with a whip. Others are monkey- and bear- ' This article is mainly compiled Hughes' Dictionary of Islam, and the from Sir E. D. Maclagan's Punjab volume on Muhannnadans of Giijai-dt Cefisus Report (i?><ji), pp. 192-196, the in the Bombay Gazetteer, pp. 20-24. article on Fakir in the Rev. T. P. ^ Hughes, p. 116.

trainers and rope-dancers. The Madaris are said to be proof against snakes and scorpions, and to have power to cure their bites. They will leap into a fire and trample it down, crying out, ' Aain Madar, Aam Madar! ^ The Gurujwale or Rafai have as their badge a spiked iron club with small chains attached to the end. The Fakir rattles the chains of his club to announce his presence, and if the people will not give him alms strikes at his own cheek or eye with the sharp point of his club, making the blood flow. They make prayers to their club once a year, so that it may not cause them serious injury when they strike themselves with it.

The Jalalias are named after their founder, Jalal-ud-din of Bokhara, and have a horse-whip as their badge, with which they sometimes strike themselves on the hands and feet. They are said to consume large quantities of bhang, and to eat snakes and scorpions ; they shave all the hair on the head and face, including the eyebrows, except a small scalp-lock on the right side. The IMewati appear to be a thieving order. They are also known as Kulchor or thieves of the family, and appear to have been originally a branch of the Madari, who were perhaps expelled on account of their thieving habits.

Their distinguishing mark is a double bag like a pack-saddle, which they hang over their shoulders.

The Sada or Musa Sohag are an order who dress like women, put on glass bangles, have their ears and noses pierced for ornaments,

and wear long hair, but retain their beards and moustaches. They regard themselves as brides of God or of Hussan, and

beg in this guise. The Nakshbandia are the disciples of Khwaja Mir Muhammad, who was called Nakshband or brocade-maker. They beg at night-time, carrying an open brass lamp with a short wick. Children are fond of the Nakshband, and go out in numbers to give him money. In return he marks them on the brow with oil from his lamp. They are quiet and well behaved, belonging to the Ba Shara class of Fakirs, and having homes and families. The Kalandaria or wandering dervishes, who are

1 Punjab Census Report (1891), p. 196.

occasionally met with, were founded by Kalandar Yusuf- ul-Andalusi, a native of Spain. Having been dismissed from another order, he founded this as a new one, with the obligation of perpetual travelling.

The Kalandar is a well- known figure in Eastern stories.^ The Maulawiyah are the well-known dancing dervishes of Constantinople and Cairo, but do not belong to India. The different orders of Fakirs are not strictly endogamous, and marriages can take place between their members, though the Madaris prefer to confine marriage to their own order. Fakirs as a body are believed to marry among themselves, and hence to form something in the nature of a caste, but they freely admit outsiders, whether Muhammadans or proselytised Hindus.

Every Fakir must have a Murshid or preceptor, and be 3- Rules initiated by him. This applies also to boys born in the customs. order, and a father cannot initiate his son. The rite is usually simple, the novice having to drink sherbet from the same cup as his preceptor and make him a present of Rs. 1-4 ; but some orders insist that the whole body of a novice should be shaved clean of hair before he is initiated. The principal religious exercise of Fakirs is known as Zikr, and consists in the continual repetition of the names of God by various methods, it being supposed that they can draw the name from different parts of the body. The exercise is so exhausting that they frequently faint under it, and is varied by repetition of certain chapters of the Koran.

The Fakir has a tasbih or rosary, often consisting of ninety-nine beads, on which he repeats the ninety-nine names of God. The Fakirs beg both from Hindus and Muhammadans, and are sometimes troublesome and importunate, inflicting wounds on themselves as a means of extorting alms. One beggar in Saugor said that he would give every one who gave him alms five strokes with his whip, and attracted considerable custom by this novel expedient. Some of them are in charge of Muhammadan cemeteries and receive fees for a burial, while others live at the tombs of saints. They keep the tomb in good repair, cover it with a green cloth and keep a lighted lamp on it, and appropriate the ^ Hughes' Dictionary of Islam, art. Fakir.

offerings made by visitors. Owing to their solitude and continuous repetition of prayers many Fakirs fall into a distraught condition, when they are known as mast, and are believed to be possessed of a spirit. At such a time the people attach the greatest importance to any utterances which fall from the Fakir's lips, believing that he has the gift of prophecy, and follow him about with presents to induce him to make some utterance.

END OF VOL. II

Printed ly R. & R. Clakk, Limited, Edinburgh.

University of California SOUTHERN REGIONAL LIBRARY FACILITY 305 De Neve Drive - Parking Lot 17 • Box 951388 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90095-1388 Return this material to the library from which it was borrowed.