Mysore State: Customs and traditions, 1909

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/>You can help by converting...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |||

|- | |- | ||

| + | |||

|colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> | ||

| − | This | + | |

| − | + | This article was written between 1907- 1909 when conditions were<br /> different.It has been archived for its historical value as well as for<br/>the insights it gives into British colonial writing about India.<br/> Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with its contents. <br/> Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II <br/> of this article. <br/> | |

| − | Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles | + | |

| + | Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles <br/>directly on their online archival encyclopædia after its formal launch. | ||

See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | See [[examples]] and a tutorial.</div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | From ''' Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1907 – 1909 ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Mysore State (Maisūr): 1909 ''' | ||

[[Category: India |M]] | [[Category: India |M]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:02, 16 February 2014

This article was written between 1907- 1909 when conditions were Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles |

From Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1907 – 1909

Mysore State (Maisūr): 1909

Contents |

[edit] Clothes and jewellery

White or coloured cotton stuffs of stout texture supply the principal dress of the people, with a woollen kambli or blanket as an outer covering for the night or a protection against cold or damp. Brāhmans go bare-headed, the head being shaved all except the tuft at the crown, and most Hindus observe the same practice. The moustache is the only hair worn on the face.

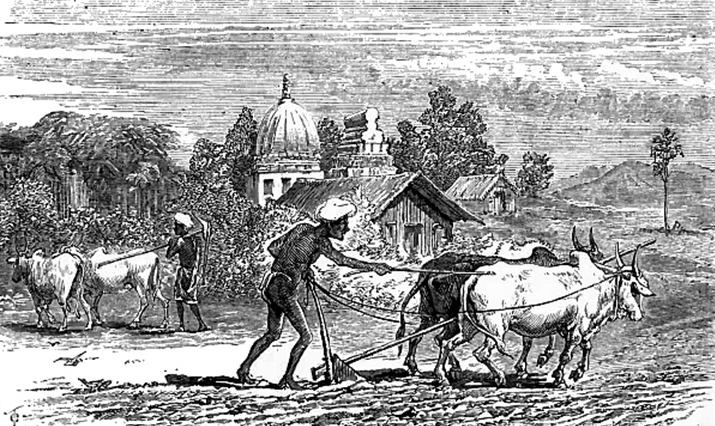

The dhotra, a thin sheet, covers the lower limbs, one end being gathered into folds in front and the other [S. 207] passed between the legs and tucked in at the waist behind. A similar garment is thrown over the shoulders. A bright magenta worsted cap and a scarlet, green, or blue blanket are often worn in the early morning or on a journey. At office, Brāhmans wear a turban and a long coat, either woollen or cotton. Students wear a sort of smoking-cap instead of a turban. The ryots are generally content with a turban and a kambli, with commonly a short pair of drawers. When not at work they often wear a blouse or short smock-frock.

The dress of the women is graceful and becoming. A tight-fitting short bodice is universally worn, leaving the arms, neck, throat, and middle bare, the two ends being tied in a knot in front. It is generally of a gay colour, or variegated with borders and gussets of contrasting tints, which set off the figure to advantage. In the colder tracts, to the west, a somewhat loose jacket, covering all the upper part of the body and the arms, is worn instead.

The shīre or sārī, a long sheet, ordinarily dark blue or a dull red with yellow borders, is wrapped round the lower part of the body, coming down to the ankles. One end is gathered into a large bunch of folds in front, while the other, passed across the bosom and over the head, hangs freely over the right shoulder. In the west it is tied there in a knot. Brāhman women pass the lower end of the cloth between the legs and tuck it in at the waist behind, which leaves the limbs more free.

Their heads too are not covered, the hair being gathered into one large plait, which hangs straight down the back, very effectively decorated at the crown and at different points with richly chased circular golden cauls or bosses. Vaisya women are similarly dressed, but often with less good taste. They smear themselves with saffron to produce a fair or yellow tint, and not only on their cheeks but also over their arms and legs. This practice, so common among the trading class, is by no means attractive, nor is the habit of blackening the teeth, adopted by married women, more pleasing to European ideas.

Many fair women are elaborately tattooed on the arms. Sūdra women generally gather the hair into a chignon or bunch behind, stuffed out with a bunch of wool, and run a large pin through, with an ornamental silver head, which is rather becoming. In the Malnād the women often arrange the back hair in a very picturesque manner, with a plait of the cream-white ketaki flower (Pandanus odoratissimus), or with orchid blossoms or pink cluster-roses. Ornaments are commonly worn by all classes in the ears and nose, and on the arms, with rings on the fingers and toes, and as many and costly necklets and chains round the neck as means will allow.

Chains frequently connect the upper rim of the ear with the ornamental pin in the back hair, and have a pretty effect. The richer Brāhman and other girls wear silver anklets, often of a very ponderous make, which are by no means elegant. A silver zone [S. 208] clasped in front is a common article of attire among all but the poorer women, and gives a pleasing finish to the costume. The only marked difference is in the dress of Lambāni women, already described in treating of them.

In Manjarābād the dress of the headmen is usually a black kambli or blanket, passed round the body and fastened over the left shoulder, leaving the right arm free. The waist is girded with a similar article, or with a cloth, generally dark blue with a white stripe. The turbans are mostly white, or dark blue with a narrow gold edging. The labourers have a similar dress of coarser material, and usually wear a leathern skull-cap. All classes carry a big knife, fastened to the girdle behind.

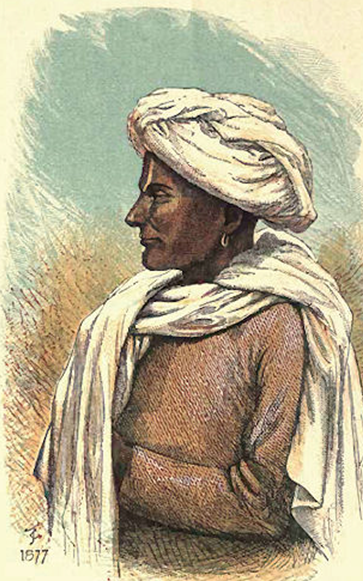

The dress of Muhammadan males differs from that of the Hindus chiefly in cut and colour, and in the wearing of long loose drawers. But for undress a piece of dark plaided stuff is worn like the dhotra. They shave the head completely, but retain all the hair of the face. A skull-cap is worn, over which the turban is tied in full dress. The women wear a coloured petticoat and bodice, with a large white sheet enveloping the head and the whole person, and pulled also over the face.

The higher caste Hindus wear leathern slippers, curled up at the toe and turned down at the heel ; the labouring classes wear heavy sandals, with wooden or leathern soles and leathern straps. Muhammadans also wear the slipper, but smaller, and frequently a very substantial big shoe, covering the whole foot. Women are never shod, except occasionally on a journey, or in very stony places, when they sometimes wear sandals.

Religious mendicants appear in a variety of grotesque and harlequin costumes, with hair unshorn. But garments dyed with red ochre or saffron are the commonest indications of a sacred calling.

[edit] Customs

Animal fights, between rams, cocks, and quails, are popular. Companies of tumblers, jugglers, snake-charmers, &c., wander about and earn a living. Theatrical performances are also well patronized. In the south they take place in the open at a certain season in all the large villages, the performers being the villagers themselves.

The Hindu festivals most generally observed by all sects are the Holī and [S. 209] the Dasara, which respectively marrk the seasons of the vernal and autumnal equinox ; the Pongal, at the time of the winter solstice, a sort of harvest festival; the Dipāvali or feast of lights; and the Yugādi or new year's day.

The Sivarātri, or watch-night of fasting, is kept by all adherents of Siva. The Muhammadans keep the Ramzān, when thirty days of abstinence are observed, and also the Muharram, properly a season of lamentation, but generally kept here as a festival. Their other principal public feasts are the Bakr-īd and Shab-i-barāt.

Among respectable Hindus a man generally has three names—the first being that of his village or the place of origin of his family ; the second his personal name ; and the third that of his caste or sect. It is a common custom to name the eldest son after his paternal grandfather, and the next after his maternal grandfather, but only if they are dead. If they are living, then after the great-uncle or other corresponding near relative who is dead.

Girls are similarly named after the female grandparents, &c. But if a child was born in response to a religious vow, it is named after the god who is supposed to have granted it. Muhammadans are named after the apostle under whose star they are born, or from one of the ninety-nine sacred names, to which is added the sect. Girls are named after the wives or female relatives of the apostles.

[edit] Food habits

Rāgi (Eleusine coracana) is the staple food of all the lower orders and labouring classes. The flour is made into a kind of pudding called hittu, and into cakes, which are fried in oil. Of other millets, jola (Sorghum vulgare) is the most commonly eaten, especially in the north. Puddings and cakes are made of the flour, and it is also boiled whole to eat with curry. Of pulses, avare (Dolichos Lablab) is the favourite, and is used in curries. Rice (Oryza sativa) of many varieties is the principal food of Brāhmans and the higher classes.

[edit] Houses

The dwellings of the people are generally of mud, one-storeyed and low, with few, if any, openings outwards except the door, but possessed of courtyards within, surrounded with verandas and open to the sky. In the better class of houses these are well paved and drained, while the wooden pillars are elaborately carved or painted. The huts of the outcaste and poorer classes are thatched ; but the houses of the higher orders are covered with either terraced or tiled roofs, the latter more especially in the west, where the rainfall is heavy.

[edit]

The unmarried, the married, and the widowed are respectively 47.46, 40.34, and 12.20 per cent. of the population. Females form 41 percent. [S. 192] of the unmarried, 51 of the married, and 79 of the widowed. Christians have the highest proportion of unmarried and the lowest of widowed in both sexes. Next come Animists and Musalmāns, with lower proportions of unmarried and higher of widowed. The Jains have a higher ratio of bachelors than the Hindus, but among them spinsters are proportionately fewest and widowers and widows most numerous.

Infant marriage of girls prevails most among the Jains and Hindus, and scarcely at all among Christians, but there are cases in all religions. Of 1,000 married females, 54 are under five years of age. But of course these are really cases of betrothal, though as irrevocable as marriage, and causing widowhood if death should intervene. Chitaldroog District shows the highest proportion of such cases ; certain subdivisions of Wokkaligas there are said to have a custom of betrothing the children of near relations to one another within a few months of their birth, the tāli, or token of the marriage bond, being tied to the cradle of the infant girl.

Some of the Panchāla artisans and devotee Lingāyats seem especially given to infant marriage. By a Regulation of 1894 the marriage of girls under 8 has been prohibited in Mysore, and also that of girls under 14 to men of over 50. Of the total number of married females, 7.6 per cent. are under 15, and 12.3 per cent. between 15 and 20. Among Brāhmans and Komatis girls must be married before puberty, and in the majority of cases the ceremony takes place between 8 and 12.

In other castes girls are mostly married between the ages of 10 and 20. Above this age there are very few spinsters, and these principally among native Christians, though among Lambānis and Iruligas, classed as Animists, brides are often over 30. Of widows, more than 73 per cent. are over 40.

Roughly speaking, among Christians and Jains one widow in 3 is under 40, in the other religions one in 4. After 40 more than half the women are widows. Remarriage of widows is utterly repugnant to most Hindu castes, though permissible in some of the lower ones. It appears from the census returns that 5.8 per cent. of widows were remarried ; but this was principally among Woddas and Jogis, who are not socially very important, and among Musalmān Labbais and nomad Koramas.

Of the male sex, seven youths under 15 in 1,000 are married; from 15 to 20 there are 13.3 per cent. married and 0.2 per cent. widowers ; from 20 to 40 there are 69 per cent. married and 3.7 per cent. widowers; over 40 there are 78.7 per cent. married and 17.7 per cent. widowers.

Polygamy is rare, though allowed by all classes except Christians. Cast-off or widowed women of the lower orders sometimes attach themselves as concubines to men who have legitimate wives. Among the higher castes a second wife is taken only when the first proves barren, or is incurably ill, or immoral.

But unless put away for [S. 193] immoral conduct, the first wife alone is entitled to join the husband in religious ceremonies, and the second can do so only with her consent. The proportion of married men who have more than one wife is 18 in 1,000. Animists and Musalmāns stand highest in this respect, and next come labouring and agricultural classes such as Woddas, Idigas, Wokkaligas, and Kurubas.

There are no statistics for divorce. Polyandry and infanticide are unknown in Mysore, as also inheritance through the mother. The joint family system continues among Hindus, but modern influences are tending to break it up.