Basor

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in<br/>1916 its contents related only t...") |

|||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

as saises, because the touch of horse-dung is considered as a | as saises, because the touch of horse-dung is considered as a | ||

pollution, entailing temporary excommunication from caste, | pollution, entailing temporary excommunication from caste, | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 09:05, 5 April 2014

This article was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Basor

LIST OF PARAGRAPHS 1 . Numbers and distrlbuiion. 4. Marriage. 2. Caste traditions. 5. Religion and social status. 3. Subdivisions. 6. Occupation. Basop,

Bansphop, Dhulia, Bupud

The occupational caste of bamboo-workers, the two first names being Hindi and the last the term used in the Maratha Districts. The cognate Uriya caste is called Kandra and the Telugu one Medara. The Basors numbered 53,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berar in 191 i. About half the total number reside in the Saugor, Damoh and Jubbulpore Districts. The word Basor is a corruption of Bansphor, ' a breaker of bamboos.' Dhulia, from dholi, a drum, means a musician. The caste trace their origin from Raja Benu or Venu who ruled at Singorgarh in Damoh.

It is related of him that he was so pious that he raised no taxes from his subjects, but earned his livelihood by making and selling bamboo fans. He could of course keep no army, but he knew magic, and when he broke his fan the army of the enemy broke up in unison. Venu is a Sanskrit word meaning bamboo. But a mythological Sanskrit king called Vena is mentioned in the Puranas, from whom for his sins was born the first Nishada, the lowest of human beings, and Manu ^ states that the bamboo -worker is the issue of a ' Compiled from papers by Mr. Ram Betul ; Mr. Keshava Rao, Headmaster, Lai, B.A., De])Uty Inspector of Schools, Middle School, Seoni ; and Bapu Gulab Saugor; Mr. Vishnu Gangadhar Gadgil, Singh, Superintendent, Land Records, Tahslldar, Narsinghpur ; Mr. Devi Betul. Dayal, Tahsildar, liatta ; Mr. Kanhya ^ Chapter x. 37, and Shudra Kani- Lal, B. A., Deputy Inspector of Schools, lakar, p. 284.

Nishada or Chandal father and a Vaidcha ' mother. So that the local story may be a corruption of the Brahmanical tradition. Another legend relates that in the beginning there were no bamboos, and the first Basor took the serpent which Siva wore round his neck and going to a hill planted it with its head in the ground, A bamboo at once sprang up on the spot, and from this the liasor made the first winnowing fan. And the snake-like root of the bamboo, which no doubt suggested the story to its composer, is now adduced in proof of it.

The Basors of the northern Districts are divided into a 3- •'^"•j- number of subcastes, the principal of which are : the Purania '^^'°" • or Juthia, who perhaps represent the oldest section, Purania being from purdna old ; they are called Juthia because they eat the leavings of others ; the Barmaiya or Malaiya, apparently a territorial group ; the Deshwari or Bundel- khandi who reside in the desJi or native place of Bundel- khand ; the Gudha or Gurha, the name being derived by some from giida a pigsty ; the Dumar or Dom Basors ; the Dhubela, perhaps from the Dhobi caste ; and the Dharkar. Two or three of the above names appear to be those of other low castes from which the Basor caste may have been recruited, perhaps at times when a strong demand existed for bamboo-workers.

The Buruds do not appear to be sufficiently numerous to have subcastes. But they include a few Telenga Buruds who are really Medaras, and the caste proper are therefore sometimes known as Maratha Buruds to distinguish them from these. The caste has numerous bainks or exogamous groups or septs, the names of which may chiefly be classified as territorial and totemistic. Among the former are Mahobia, from the town of Mahoba ; Sirmaiya, from Sirmau ; Orahia, from Orai, the battlefield of the Banaphar generals, Alha and Udal ; Tikarahia from Tikari, and so on. The totemistic septs include the Sanpero from sdnp a snake, the Mangrelo from mangra a crocodile, the Morya from inor a peacock, the Titya from the titehri bird and the Sarkia from sarki or red ochre, all of which worship their respective totems. The Katarya or ' dagger ' sept worship a real or painted dagger at their marriage, and the Kemia, a branch * A Vaideha was the child of a Vaishya father and a Brahman mother. VOL. II P

of the kem tree {Stephegyne parvifolid).

The Bandrelo, from bandar^ worship a painted monkey. One or two groups are named after castes, as Bamhnelo from Brahman and Bargujaria from Bargujar Rajput, thus indicating that members of these castes became Basors and founded families. One sept is called Marha from Marhai, the goddess of cholera, and the members worship a picture of the goddess drawn in black. The name of the Kulhantia sept means somersault, and these turn a somersault before worshipping their gods. So strong is the totemistic idea that some of the territorial groups worship objects with similar names. Thus the Mahobia group, whose name is undoubtedly derived from the town of Mahoba, have adopted the mahua tree as their totem, and digging a small hole in the ground place in it a little water and the liquor made from mahua flowers, and worship it. This represents the process of distillation of country liquor. Similarly, the Orahia group, who derive their name from the town of Orai, now worship the urai or khaskhas grass, and the Tikarahia from Tikari worship a tikli or glass spangle.

Marriage

The marriage of persons belonging to the same haink or nage. s^^X. and also that of first cousins is forbidden. The age of marriage is settled by convenience, and no stigma attaches to its postponement beyond adolescence. Intrigues of un- married girls with men of their own or any higher caste are usually overlooked. The ceremony follows the standard Hindi and Marathi forms, and presents no special features. A bride-price called chdri, amounting to seven or eight rupees, is usually paid. In Betul the practice of lanijhana, or serving the father-in-law for a term of years before marrying his daughter, is sometimes followed. Widow- marriage is permitted, and the widow is expected to wed her late husband's younger brother.

The Basors are musicians by profession, but in Betul the narsingha, a peculiar kind of crooked trumpet, is the only implement which may be played at the marriage of a widow. A woman marrying a second time forfeits all interest in the property of her late husband, unless she is without issue and there are no near relatives of her husband to take it. Divorce is effected by the breaking of the woman's bangles in public. If obtained by the wife,

she must repay to her first husband the expenditure incurred by him for her marriage when she takes a second, liut the acceptance of this payment is considered derogatory and the husband refuses it unless he is poor. The liasors worship the ordinary Hindu deities and also 5. Reii- ghosts and spirits. Like the other low castes they entertain focfaf" a special veneration for Devi. They profess to exorcise evil status.

spirits and the evil eye, and to cure other disorders and dis-

eases through the agency of their incantations and the goblins who do their bidding. They burn their dead when they can

afford it and otherwise bury them, placing the corpse in the grave with its head to the north. The body of a woman is wrapped in a red shroud and that of a man in a white one. They observe mourning for a period of three to ten days,

but in Jubbulpore it always ends with the fortnight in which

the death takes place ; so that a person dying on the 15 th or 30th of the month is mourned only for one day.

They eat almost every kind of food, including beef, pork, fowls, liquor and the leavings of others, but abjure crocodiles, monkeys, snakes and rats. Many of them have now given up eating cow's flesh in deference to Hindu feeling. They will take food from almost any caste except sweepers, and one or two others, as Joshi and Jasondhi, towards whom for some unexplained reason they entertain a special aversion.

They will admit outsiders belonging to any caste from whom they can take food into the community.

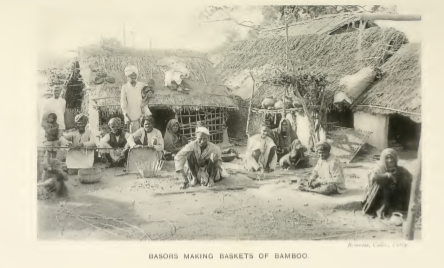

They are generally considered as impure, and live outside the village, and their touch conveys pollution, more especially in the Maratha Districts. The ordinary village menials, as the barber and washerman, will not work for them, and services of this nature are performed by men of their own community. As, however, their occupation is not in itself unclean, they rank above sweepers, Chamars and Dhobis. Temporary exclusion from caste is imposed for the usual offences, and the almost invariable penalty for readmission is a feast to the caste- fellows. A person, male or female, who has been convicted of adultery must have the head shaved, and is then seated in the centre of the caste-fellows and pelted by them with the leavings of their food. Basor women are not permitted to wear nose-rings on pain of exclusion from caste. 212 BEDAR PART 6. Occupa- The trade of the Basors is a very essential one to the ^'°°- agricultural community. They make numerous kinds of baskets, among which may be mentioned the chujika, a very small one, the tokni, a basket of middle size, and the iokna, a very large one.

The dauri is a special basket with a lining of matting for washing rice in a stream. The jhdnpi is a round basket with a cover for holding clothes ; the tipanna a small one in which girls keep dolls ; and the bilahra a still smaller one for holding betel-leaf. Other articles made from bamboo-bark are the chalni or sieve, the khunkhwia or rattle, the bdnsuri or wooden flute, the bijna or fan, and the supa or winnowing-fan. All grain is cleaned with the help of the supa both on the threshing-floor and in the house before consumption, and a child is always laid in one as soon as it is born. In towns the Basors make the bamboo matting which is so much used. The only imple- ment they employ is the bdnka, a heavy curved knife, with which all the above articles are made. The bdnka is duly worshipped at the Diwali festival. The Basors are also the village musicians, and a band of three or four of them play at weddings and on other festive occasions. Some of them work as pig-breeders and others are village watchmen. The women often act as midwives. One subcaste, the Dumar, will do scavenger's work, but they never take employment as saises, because the touch of horse-dung is considered as a pollution, entailing temporary excommunication from caste,