Paliyans of Madura

(Created page with " {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article is an excerpt from<br/> ''' Castes and Tribes of Southern India ''' <br/> By '' Edgar Thurston,...") |

|||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

[[Category:Communities|P]] | [[Category:Communities|P]] | ||

| − | Paliyans of Madura and Tinnevelly. In a note on the Malai (hill) Paliyans of the Madura district, the Rev. J. E. Tracy writes as follows. “I went to their village at the foot of the Periyar hills, and can testify to their being the most abject, hopeless, and unpromising specimens of humanity that I have ever seen. There were about forty of them in the little settlement, which was situated in a lovely spot. A stream of pure water was flowing within a few feet of their huts, and yet they were as foul and filthy in their personal appearance as if they were mere animals, and very unclean ones. Rich land that produced a luxuriant crop of rank reeds was all around them, and, with a little exertion on their part, might have been abundantly irrigated, and produced continuous crops of grain. Yet they lived entirely on nuts and roots, and various kinds of gum that they gathered in the forest on the slopes of the hills above their settlement. Only two of the community had ever been more than seven miles away from their village into the open country below them. Their huts were built entirely of grass, and consisted of only one room each, and that open at the ends. The chief man of the community was an old man with white hair. His distinctive privilege was that he was allowed to sleep between two fires at night, while no one else was allowed to have but one—a distinction that they were very complaisant about, perhaps because with the distinction was the accompanying obligation to see that the community’s fire never went out. As he was also the only man in the community who was allowed to have two wives, I inferred that he delegated to them the privilege of looking after the fires, while he did the sleeping, whereas, in other families, the man and wife had to take turn and turn about to see that the fire had not to be re-lighted in the morning. They were as ignorant as they were filthy. They had no place of worship, but seemed to [463]agree that the demons of the forest around them were the only beings that they had to fear besides the Forest Department. They were barely clothed, their rags being held about them, in one or two cases, with girdles of twisted grass. They had much the same appearance that many a famine subject presented in the famine of 1877, but they seemed to have had no better times to look back upon, and hence took their condition as a matter of course. The forest had been their home from time immemorial. Yet the forest seemed to have taught them nothing more than it might have been supposed to have taught the prowling jackal or the laughing hyæna. There were no domesticated animals about their place: strange to say, not even a pariah dog. They appeared to have no idea of hunting, any more than they had of agriculture. And, as for any ideas of the beauty or solemnity of the place that they had selected as their village site, they were as innocent of such things as they were of the beauties of Robert Browning’s verse.” | + | Paliyans of Madura and Tinnevelly. In a note on the Malai (hill) Paliyans of the Madura district, the Rev. J. E. Tracy writes as follows. “I went to their village at the foot of the Periyar hills, and can testify to their being the most abject, hopeless, and unpromising specimens of humanity that I have ever seen. There were about forty of them in the little settlement, which was situated in a lovely spot. A stream of pure water was flowing within a few feet of their huts, and yet they were as foul and filthy in their personal appearance as if they were mere animals, and very unclean ones. Rich land that produced a luxuriant crop of rank reeds was all around them, and, with a little exertion on their part, might have been abundantly irrigated, and produced continuous crops of grain. Yet they lived entirely on nuts and roots, and various kinds of gum that they gathered in the forest on the slopes of the hills above their settlement. Only two of the community had ever been more than seven miles away from their village into the open country below them. |

| + | |||

| + | Their huts were built entirely of grass, and consisted of only one room each, and that open at the ends. The chief man of the community was an old man with white hair. His distinctive privilege was that he was allowed to sleep between two fires at night, while no one else was allowed to have but one—a distinction that they were very complaisant about, perhaps because with the distinction was the accompanying obligation to see that the community’s fire never went out. As he was also the only man in the community who was allowed to have two wives, I inferred that he delegated to them the privilege of looking after the fires, while he did the sleeping, whereas, in other families, the man and wife had to take turn and turn about to see that the fire had not to be re-lighted in the morning. They were as ignorant as they were filthy. They had no place of worship, but seemed to [463]agree that the demons of the forest around them were the only beings that they had to fear besides the Forest Department. They were barely clothed, their rags being held about them, in one or two cases, with girdles of twisted grass. They had much the same appearance that many a famine subject presented in the famine of 1877, but they seemed to have had no better times to look back upon, and hence took their condition as a matter of course. The forest had been their home from time immemorial. Yet the forest seemed to have taught them nothing more than it might have been supposed to have taught the prowling jackal or the laughing hyæna. There were no domesticated animals about their place: strange to say, not even a pariah dog. They appeared to have no idea of hunting, any more than they had of agriculture. And, as for any ideas of the beauty or solemnity of the place that they had selected as their village site, they were as innocent of such things as they were of the beauties of Robert Browning’s verse.” | ||

In a note written in 1817, Mr. T. Turnbull states that the Madura Pulliers “are never seen unless when they come down to travellers to crave a piece of tobacco or a rag of cloth, for which they have a great predilection. The women are said to lay their infants on warm ashes after delivery, as a substitute for warm clothing and beds.” | In a note written in 1817, Mr. T. Turnbull states that the Madura Pulliers “are never seen unless when they come down to travellers to crave a piece of tobacco or a rag of cloth, for which they have a great predilection. The women are said to lay their infants on warm ashes after delivery, as a substitute for warm clothing and beds.” | ||

| Line 32: | Line 34: | ||

| − | A detailed account of the Paliyans of the Palni hills by the Rev. F. Dahmen has recently been published,10 to which I am indebted for the following information. “The Paliyans are a nomadic tribe, who for the most part rove in small parties through the jungle-clad gorges that fringe the Upper Palnis plateau. There they maintain themselves mostly on the products of the chase and on roots (yams, etc.), leaves and wild fruits (e.g., of the wild date tree), at times also by hiring their labour to the Kunnuvan or Mannadi villagers. The find of a bee-hive in the hollow of some tree is a veritable feast for them. No sooner have they smoked the bees out than they greedily snatch at the combs, and ravenously devour them on the spot, with wax, grubs, and all. Against ailments the Paliyans have their own remedies: in fact, some Paliyans have made a name for themselves by their knowledge of the medicinal properties of herbs and roots. | + | A detailed account of the Paliyans of the Palni hills by the Rev. F. Dahmen has recently been published,10 to which I am indebted for the following information. “The Paliyans are a nomadic tribe, who for the most part rove in small parties through the jungle-clad gorges that fringe the Upper Palnis plateau. There they maintain themselves mostly on the products of the chase and on roots (yams, etc.), leaves and wild fruits (e.g., of the wild date tree), at times also by hiring their labour to the Kunnuvan or Mannadi villagers. The find of a bee-hive in the hollow of some tree is a veritable feast for them. No sooner have they smoked the bees out than they greedily snatch at the combs, and ravenously devour them on the spot, with wax, grubs, and all. Against ailments the Paliyans have their own remedies: in fact, some Paliyans have made a name for themselves by their knowledge of the medicinal properties of herbs and roots. |

| − | Concerning the religion and superstitions of the Paliyans, the Rev. F. Dahmen writes as follows. “The principal religious ceremony takes place about the beginning of March. Mayāndi (the god) is usually represented by a stone, preferably one to which nature has given some curious shape, the serpent form being especially valued. I said ‘represented,’ for, according to our Paliyans, the stone itself is not the god, who is supposed to live somewhere, they do not exactly know where. The stone that represents him has its shrine at the foot of a tree, or is simply sheltered by a small thatched covering. There, on the appointed day, the Paliyans gather before sunrise. Fire is made in a hole in front of the sacred stone, a fine cock brought in, decapitated amidst the music of horn and drum and the blood made to drip on the fire. The head of the fowl ought to be severed at one blow, as this is a sign of the satisfaction of the god for the past, and of further protection for the future. Should the head still hang, this would be held a bad omen, foreboding calamities for the year ensuing. The instrument used in this sacred operation is the aruvāl, but the sacrificial aruvāl cannot be used but for this holy purpose. Powers of witchcraft and magic are attributed to the Paliyans by other castes, and probably believed in by themselves. The following device adopted by them to protect themselves from the attacks of wild animals, the panther in particular, may be given as an illustration. Four jackals’ tails are planted in four different spots, chosen so as to include the area within which they wish to be safe from the claws of the brute. This is deemed protection enough: though panthers should enter the magic square, they could do the Paliyans no harm; their mouths are locked.” It is noted by the Rev. F. Dahmen that Paliyans sometimes go on a pilgrimage to the Hindu shrine of Subrahmaniyam at Palni. | + | Thus, for instance, they make from certain roots (periya uri katti vēr) a white powder known as a very effective purgative. Against snake-bite they always carry with them certain leaves (naru valli vēr), which they hold to be a very efficient antidote. As soon one of them is bitten, he chews these, and also applies them to the wound. Patience and cunning above all are required in their hunting-methods. One of their devices, used for big game, e.g., against the sambar (deer), or against the boar, consists in digging pitfalls, carefully covered up with twigs and leaves. On the animal being entrapped, it is dispatched with clubs or the aruvāl (sickle). Another means consists in arranging a heap of big stones on a kind of platform, one end of which is made to rest on higher ground, the other skilfully equipoised by a stick resting on a fork, where it remains fixed by means of strong twine so disposed that the least movement makes the lever-like stick on the fork fly off, while the platform and the stones come rapidly down with a crash. |

| + | |||

| + | The string which secures the lever is so arranged as to unloose itself at the least touch, and the intended victim can hardly taste the food that serves for bait without bringing the platform with all its weight down upon itself. Similar traps, but on a smaller scale, are used to catch smaller animals: hares, wild fowl, etc. Flying squirrels are smoked out of the hollows of trees, and porcupines out of their burrows, and then captured or clubbed to death on their coming out. The first drops of blood of any animal the Paliyans kill are offered to their god. A good catch is a great boon for the famished Paliyan. The meat obtained therefrom must be divided between all the families of the settlement. The skins, if valuable, are preserved to barter for the little commodities they may stand in need of, or to give as a tribute to their chief. One of their methods for procuring fish consists in throwing the leaves of a creeper called in Tamil karungakodi, after rubbing them, into the water. Soon the fish is seen floating on the surface. Rough fashioned hooks are also used. When not engaged on some expedition, or not working for hire, the Paliyans at times occupy themselves in the fabrication of small bird-cages, or in weaving a rough kind of mat, or in basket-making. The small nicknacks they turn out are made according to rather ingenious patterns, and partly coloured with red and green vegetable dyes. These, with the skins of animals, and the odoriferous resin collected from the dammer tree, are about the only articles which they barter or sell to the inhabitants of the plains, or to the Mannadis.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Concerning the religion and superstitions of the Paliyans, the Rev. F. Dahmen writes as follows. “The principal religious ceremony takes place about the beginning of March. Mayāndi (the god) is usually represented by a stone, preferably one to which nature has given some curious shape, the serpent form being especially valued. I said ‘represented,’ for, according to our Paliyans, the stone itself is not the god, who is supposed to live somewhere, they do not exactly know where. The stone that represents him has its shrine at the foot of a tree, or is simply sheltered by a small thatched covering. There, on the appointed day, the Paliyans gather before sunrise. Fire is made in a hole in front of the sacred stone, a fine cock brought in, decapitated amidst the music of horn and drum and the blood made to drip on the fire. The head of the fowl ought to be severed at one blow, as this is a sign of the satisfaction of the god for the past, and of further protection for the future. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Should the head still hang, this would be held a bad omen, foreboding calamities for the year ensuing. The instrument used in this sacred operation is the aruvāl, but the sacrificial aruvāl cannot be used but for this holy purpose. Powers of witchcraft and magic are attributed to the Paliyans by other castes, and probably believed in by themselves. The following device adopted by them to protect themselves from the attacks of wild animals, the panther in particular, may be given as an illustration. Four jackals’ tails are planted in four different spots, chosen so as to include the area within which they wish to be safe from the claws of the brute. This is deemed protection enough: though panthers should enter the magic square, they could do the Paliyans no harm; their mouths are locked.” It is noted by the Rev. F. Dahmen that Paliyans sometimes go on a pilgrimage to the Hindu shrine of Subrahmaniyam at Palni. | ||

Writing concerning the Paliyans who live on the Travancore frontier near Shenkotta, Mr. G. F. D’Penha states11 that they account for their origin by saying that, at some very remote period, an Eluvan took refuge during a famine in the hills, and there took to wife a Palliyar woman, and that the Palliyars are descended from these two. “The Palliyar,” he continues, “is just a shade lower than the Eluvan. He is permitted to enter the houses of Eluvans, Elavanians (betel-growers), and even of Maravars, and in the hills, where the rigour of the social code is relaxed to suit circumstances, the higher castes mentioned will even drink water given by Palliyars, and eat roots cooked by them. The Palliyars regard sylvan deities with great veneration. Kurupuswāmi is the tribe’s tutelary god, and, when a great haul of wild honey is made, offerings are given at some shrine. They pretend to be followers of Siva, and always attend the Adi Amavasai ceremonies at Courtallum. The Palliyar cultivates nothing, not even a sweet potato. He keeps no animal, except a stray dog or two. An axe, a knife, and a pot are all the impedimenta he carries. An [469]expert honey-hunter, he will risk his neck climbing lofty precipices or precipitous cliffs. A species of sago-palm furnishes him with a glairy glutinous fluid on which he thrives, and such small animals as the iguana (Varanus), the tortoise, and the larvae of hives are never-failing luxuries.” | Writing concerning the Paliyans who live on the Travancore frontier near Shenkotta, Mr. G. F. D’Penha states11 that they account for their origin by saying that, at some very remote period, an Eluvan took refuge during a famine in the hills, and there took to wife a Palliyar woman, and that the Palliyars are descended from these two. “The Palliyar,” he continues, “is just a shade lower than the Eluvan. He is permitted to enter the houses of Eluvans, Elavanians (betel-growers), and even of Maravars, and in the hills, where the rigour of the social code is relaxed to suit circumstances, the higher castes mentioned will even drink water given by Palliyars, and eat roots cooked by them. The Palliyars regard sylvan deities with great veneration. Kurupuswāmi is the tribe’s tutelary god, and, when a great haul of wild honey is made, offerings are given at some shrine. They pretend to be followers of Siva, and always attend the Adi Amavasai ceremonies at Courtallum. The Palliyar cultivates nothing, not even a sweet potato. He keeps no animal, except a stray dog or two. An axe, a knife, and a pot are all the impedimenta he carries. An [469]expert honey-hunter, he will risk his neck climbing lofty precipices or precipitous cliffs. A species of sago-palm furnishes him with a glairy glutinous fluid on which he thrives, and such small animals as the iguana (Varanus), the tortoise, and the larvae of hives are never-failing luxuries.” | ||

| Line 44: | Line 52: | ||

The Paliyans, whom I investigated in North Tinnevelly, were living in the jungles near the base of the mountains, in small isolated communities separated from each other by a distance of several miles. They speak Tamil with a peculiar intonation, which recalls to mind the Irulas. They are wholly illiterate, and only a few can count up to ten. A woman has been known to forget her own name. At a marriage, the father, taking the hand of the bride, and putting it into that of the bridegroom, says “I give this girl to you. Give her roots and leaves, and protect her.” The value of a bride or bridegroom depends very much on the quantity of roots, etc., which he or she can collect. When a widow does not remarry, the males of the community supply her with roots and other products of the jungle. Marriages are, as a rule, contracted within the settlement, and complications occasionally occur owing to the absence of a girl of suitable age for a young man. Indeed, in one settlement I came across two brothers, who had for this reason resorted to the adelphous form of polyandry. It would be interesting to note hereafter if this custom, thus casually introduced, becomes established in the tribe. As an exception to the rule of marriage within the settlement, it was noted that a party of Paliyans had wandered from the Gandamanaikanūr forests to the jungle of Ayanarkoil, and there intermarried with the members of the local tribe, with which they became incorporated. The Paliyans admit members [470]of other castes into their ranks. A case was narrated to me, in which a Maravan cohabited for some time with a Paliya woman, who bore children by him. In this way is the purity of type among the jungle tribes lost as the result of civilisation, and their nasal index reduced from platyrhine to mesorhine dimensions. | The Paliyans, whom I investigated in North Tinnevelly, were living in the jungles near the base of the mountains, in small isolated communities separated from each other by a distance of several miles. They speak Tamil with a peculiar intonation, which recalls to mind the Irulas. They are wholly illiterate, and only a few can count up to ten. A woman has been known to forget her own name. At a marriage, the father, taking the hand of the bride, and putting it into that of the bridegroom, says “I give this girl to you. Give her roots and leaves, and protect her.” The value of a bride or bridegroom depends very much on the quantity of roots, etc., which he or she can collect. When a widow does not remarry, the males of the community supply her with roots and other products of the jungle. Marriages are, as a rule, contracted within the settlement, and complications occasionally occur owing to the absence of a girl of suitable age for a young man. Indeed, in one settlement I came across two brothers, who had for this reason resorted to the adelphous form of polyandry. It would be interesting to note hereafter if this custom, thus casually introduced, becomes established in the tribe. As an exception to the rule of marriage within the settlement, it was noted that a party of Paliyans had wandered from the Gandamanaikanūr forests to the jungle of Ayanarkoil, and there intermarried with the members of the local tribe, with which they became incorporated. The Paliyans admit members [470]of other castes into their ranks. A case was narrated to me, in which a Maravan cohabited for some time with a Paliya woman, who bore children by him. In this way is the purity of type among the jungle tribes lost as the result of civilisation, and their nasal index reduced from platyrhine to mesorhine dimensions. | ||

| − | The Tinnevelly Paliyans say that Valli, the wife of the god Subramaniya, was a Paliyan woman. As they carry no pollution, they are sometimes employed, in return for food, as night watchmen at the Vaishnavite temple known as Azhagar Koil at the base of the hills. They collect for the Forest Department minor produce in the form of root-bark of Ventilago madraspatana and Anisochilus carnosus, the fruit of Terminalia Chebula (myrabolams), honey, bees-wax, etc., which are handed over to a contractor in exchange for rice, tobacco, betel leaves and nuts, chillies, tamarinds and salt. The food thus earned as wages is supplemented by yams (tubers of Dioscorea) and roots, which are dug up with a digging-stick, and forest fruits. They implicitly obey the contractor, and it was mainly through his influence that I was enabled to interview them, and measure their bodies, in return for a banquet, whereof they partook seated on the grass in two semicircles, the men in front and women in the rear, and eating off teak leaf plates piled high with rice and vegetables. Though the prodigious mass of food provided was greedily devoured till considerable abdominal distension was visible, dissatisfaction was expressed because it included no meat (mutton), and I had not brought new loin-cloths for them. They laughed, however, when I expressed a hope that they would abandon their dirty cloths, turkey-red turbans and European bead necklaces, and revert to the primitive leafy garment of their forbears. A struggle ensued for [471]the limited supply of sandal paste, with which a group of men smeared their bodies, in imitation of the higher classes, before they were photographed. A feast given to the Paliyans by some missionaries was marred at the outset by the unfortunate circumstance that betel and tobacco were placed by the side of the food, these articles being of evil omen as they are placed in the grave with the dead. A question whether they eat beef produced marked displeasure, and even roused an apathetic old woman to grunt “Your other questions are fair. You have no right to ask that.” If a Paliyan happens to come across the carcase of a cow or buffalo near a stream, it is abandoned, and not approached for a long time. Leather they absolutely refuse to touch, and one of them declined to carry my camera box, because he detected that it had a leather strap. | + | The Tinnevelly Paliyans say that Valli, the wife of the god Subramaniya, was a Paliyan woman. As they carry no pollution, they are sometimes employed, in return for food, as night watchmen at the Vaishnavite temple known as Azhagar Koil at the base of the hills. They collect for the Forest Department minor produce in the form of root-bark of Ventilago madraspatana and Anisochilus carnosus, the fruit of Terminalia Chebula (myrabolams), honey, bees-wax, etc., which are handed over to a contractor in exchange for rice, tobacco, betel leaves and nuts, chillies, tamarinds and salt. The food thus earned as wages is supplemented by yams (tubers of Dioscorea) and roots, which are dug up with a digging-stick, and forest fruits. They implicitly obey the contractor, and it was mainly through his influence that I was enabled to interview them, and measure their bodies, in return for a banquet, whereof they partook seated on the grass in two semicircles, the men in front and women in the rear, and eating off teak leaf plates piled high with rice and vegetables. |

| + | |||

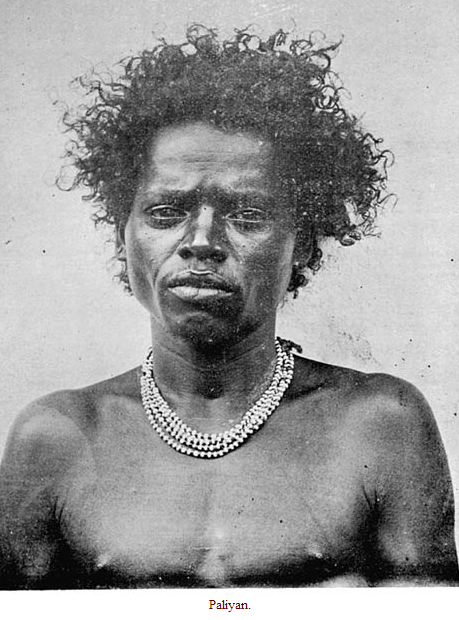

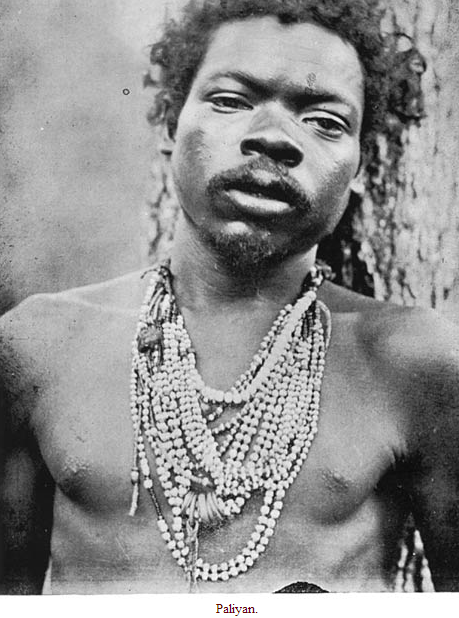

| + | Though the prodigious mass of food provided was greedily devoured till considerable abdominal distension was visible, dissatisfaction was expressed because it included no meat (mutton), and I had not brought new loin-cloths for them. They laughed, however, when I expressed a hope that they would abandon their dirty cloths, turkey-red turbans and European bead necklaces, and revert to the primitive leafy garment of their forbears. A struggle ensued for [471]the limited supply of sandal paste, with which a group of men smeared their bodies, in imitation of the higher classes, before they were photographed. A feast given to the Paliyans by some missionaries was marred at the outset by the unfortunate circumstance that betel and tobacco were placed by the side of the food, these articles being of evil omen as they are placed in the grave with the dead. A question whether they eat beef produced marked displeasure, and even roused an apathetic old woman to grunt “Your other questions are fair. You have no right to ask that.” If a Paliyan happens to come across the carcase of a cow or buffalo near a stream, it is abandoned, and not approached for a long time. Leather they absolutely refuse to touch, and one of them declined to carry my camera box, because he detected that it had a leather strap. | ||

They make fire with a quartz strike-a-light and steel and the floss of the silk-cotton tree (Bombax malabaricum). They have no means of catching or killing animals, birds, or fish with nets, traps, or weapons, but, if they come across the carcase of a goat or deer in the forest, they will roast and eat it. They catch “vermin” (presumably field rats) by smoking them out of their holes, or digging them out with their digging-sticks. Crabs are caught for eating by children, by letting a string with a piece of cloth tied to the end down the hole, and lifting it out thereof when the crab seizes hold of the cloth with its claws. Of wild beasts they are not afraid, and scare them away by screaming, clapping the hands, and rolling down stones into the valleys. I saw one man, who had been badly mauled by a tiger on the buttock and thigh when he was asleep with his wife and child in a cave. During the dry season they live in natural caves and crevices in rocks, but, if these leak [472]during the rains, they erect a rough shed with the floor raised on poles off the ground, and sloping grass roof, beneath which a fire is kept burning at night, not only for warmth, but also to keep off wild beasts. They are expert at making rapidly improvised shelters at the base of hollow trees by cutting away the wood on one side with a bill-hook. Thus protected, they were quite snug and happy during a heavy shower, while we were miserable amid the drippings from an umbrella and a mango tree. | They make fire with a quartz strike-a-light and steel and the floss of the silk-cotton tree (Bombax malabaricum). They have no means of catching or killing animals, birds, or fish with nets, traps, or weapons, but, if they come across the carcase of a goat or deer in the forest, they will roast and eat it. They catch “vermin” (presumably field rats) by smoking them out of their holes, or digging them out with their digging-sticks. Crabs are caught for eating by children, by letting a string with a piece of cloth tied to the end down the hole, and lifting it out thereof when the crab seizes hold of the cloth with its claws. Of wild beasts they are not afraid, and scare them away by screaming, clapping the hands, and rolling down stones into the valleys. I saw one man, who had been badly mauled by a tiger on the buttock and thigh when he was asleep with his wife and child in a cave. During the dry season they live in natural caves and crevices in rocks, but, if these leak [472]during the rains, they erect a rough shed with the floor raised on poles off the ground, and sloping grass roof, beneath which a fire is kept burning at night, not only for warmth, but also to keep off wild beasts. They are expert at making rapidly improvised shelters at the base of hollow trees by cutting away the wood on one side with a bill-hook. Thus protected, they were quite snug and happy during a heavy shower, while we were miserable amid the drippings from an umbrella and a mango tree. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:36, 7 April 2014

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Paliyans of Madura and Tinnevelly. In a note on the Malai (hill) Paliyans of the Madura district, the Rev. J. E. Tracy writes as follows. “I went to their village at the foot of the Periyar hills, and can testify to their being the most abject, hopeless, and unpromising specimens of humanity that I have ever seen. There were about forty of them in the little settlement, which was situated in a lovely spot. A stream of pure water was flowing within a few feet of their huts, and yet they were as foul and filthy in their personal appearance as if they were mere animals, and very unclean ones. Rich land that produced a luxuriant crop of rank reeds was all around them, and, with a little exertion on their part, might have been abundantly irrigated, and produced continuous crops of grain. Yet they lived entirely on nuts and roots, and various kinds of gum that they gathered in the forest on the slopes of the hills above their settlement. Only two of the community had ever been more than seven miles away from their village into the open country below them.

Their huts were built entirely of grass, and consisted of only one room each, and that open at the ends. The chief man of the community was an old man with white hair. His distinctive privilege was that he was allowed to sleep between two fires at night, while no one else was allowed to have but one—a distinction that they were very complaisant about, perhaps because with the distinction was the accompanying obligation to see that the community’s fire never went out. As he was also the only man in the community who was allowed to have two wives, I inferred that he delegated to them the privilege of looking after the fires, while he did the sleeping, whereas, in other families, the man and wife had to take turn and turn about to see that the fire had not to be re-lighted in the morning. They were as ignorant as they were filthy. They had no place of worship, but seemed to [463]agree that the demons of the forest around them were the only beings that they had to fear besides the Forest Department. They were barely clothed, their rags being held about them, in one or two cases, with girdles of twisted grass. They had much the same appearance that many a famine subject presented in the famine of 1877, but they seemed to have had no better times to look back upon, and hence took their condition as a matter of course. The forest had been their home from time immemorial. Yet the forest seemed to have taught them nothing more than it might have been supposed to have taught the prowling jackal or the laughing hyæna. There were no domesticated animals about their place: strange to say, not even a pariah dog. They appeared to have no idea of hunting, any more than they had of agriculture. And, as for any ideas of the beauty or solemnity of the place that they had selected as their village site, they were as innocent of such things as they were of the beauties of Robert Browning’s verse.”

In a note written in 1817, Mr. T. Turnbull states that the Madura Pulliers “are never seen unless when they come down to travellers to crave a piece of tobacco or a rag of cloth, for which they have a great predilection. The women are said to lay their infants on warm ashes after delivery, as a substitute for warm clothing and beds.”

The Palayans, or Pulleer, are described by General Burton9 as “good trackers, and many of them carried bows and arrows, and a few even possessed matchlocks. I met one of these villagers going out on a sporting excursion. He had on his head a great chatty (earthen pot) full of water, and an old brass-bound matchlock It was the height of the dry season. He was taking water to a hollow in a rock, which he kept carefully replenished, and then ensconced himself in a clump of bushes hard by, and waited all day, if necessary, with true native patience, for hog, deer, or pea-fowl to approach his ambush.”

In the Madura Manual, it is noted that “the Poleiyans have always been the prædial slaves of the Kunuvans. According to the survey account, they are the aborigines of the Palni hills. The marriage ceremony consists merely of a declaration of consent made by both parties at a feast, to which all their relatives are invited. As soon as a case of small-pox occurs in one of their villages, a cordon is drawn round it, and access to other villages is denied to all the inhabitants of the infected locality, who at once desert their homes, and camp out for a sufficiently long period. The individual attacked is left to his fate, and no medicine is exhibited to him, as it is supposed that the malady is brought on solely by the just displeasure of the gods. They bury their dead.”

The Paliyans are described, in the Gazetteer of the Madura district, as a “very backward caste, who reside in small scattered parties amid the jungles of the Upper Palnis and the Varushanād valley. They speak Tamil with a peculiar intonation, which renders it scarcely intelligible. They are much less civilised than the Pulaiyans, but do not eat beef, and consequently carry no pollution. They sometimes build themselves grass huts, but often they live on platforms up trees, in caves, or under rocks. Their clothes are of the scantiest and dirtiest, and are sometimes eked out with grass or leaves. They live upon roots (yams), leaves, and honey. They cook the roots by putting them into a pit in the ground, heaping wood upon them, and lighting it. The fire is usually kept burning all night as a protection against wild beasts, and it is often the only sign of the presence of the Paliyans in a jungle, for they are shy folk, who avoid other people. They make fire with quartz and steel, using the floss of the silk-cotton tree as tinder. Weddings are conducted without ceremonies, the understanding being that the man shall collect food and the woman cook it. When one of them dies, the rest leave the body as it is, and avoid the spot for some months.

A detailed account of the Paliyans of the Palni hills by the Rev. F. Dahmen has recently been published,10 to which I am indebted for the following information. “The Paliyans are a nomadic tribe, who for the most part rove in small parties through the jungle-clad gorges that fringe the Upper Palnis plateau. There they maintain themselves mostly on the products of the chase and on roots (yams, etc.), leaves and wild fruits (e.g., of the wild date tree), at times also by hiring their labour to the Kunnuvan or Mannadi villagers. The find of a bee-hive in the hollow of some tree is a veritable feast for them. No sooner have they smoked the bees out than they greedily snatch at the combs, and ravenously devour them on the spot, with wax, grubs, and all. Against ailments the Paliyans have their own remedies: in fact, some Paliyans have made a name for themselves by their knowledge of the medicinal properties of herbs and roots.

Thus, for instance, they make from certain roots (periya uri katti vēr) a white powder known as a very effective purgative. Against snake-bite they always carry with them certain leaves (naru valli vēr), which they hold to be a very efficient antidote. As soon one of them is bitten, he chews these, and also applies them to the wound. Patience and cunning above all are required in their hunting-methods. One of their devices, used for big game, e.g., against the sambar (deer), or against the boar, consists in digging pitfalls, carefully covered up with twigs and leaves. On the animal being entrapped, it is dispatched with clubs or the aruvāl (sickle). Another means consists in arranging a heap of big stones on a kind of platform, one end of which is made to rest on higher ground, the other skilfully equipoised by a stick resting on a fork, where it remains fixed by means of strong twine so disposed that the least movement makes the lever-like stick on the fork fly off, while the platform and the stones come rapidly down with a crash.

The string which secures the lever is so arranged as to unloose itself at the least touch, and the intended victim can hardly taste the food that serves for bait without bringing the platform with all its weight down upon itself. Similar traps, but on a smaller scale, are used to catch smaller animals: hares, wild fowl, etc. Flying squirrels are smoked out of the hollows of trees, and porcupines out of their burrows, and then captured or clubbed to death on their coming out. The first drops of blood of any animal the Paliyans kill are offered to their god. A good catch is a great boon for the famished Paliyan. The meat obtained therefrom must be divided between all the families of the settlement. The skins, if valuable, are preserved to barter for the little commodities they may stand in need of, or to give as a tribute to their chief. One of their methods for procuring fish consists in throwing the leaves of a creeper called in Tamil karungakodi, after rubbing them, into the water. Soon the fish is seen floating on the surface. Rough fashioned hooks are also used. When not engaged on some expedition, or not working for hire, the Paliyans at times occupy themselves in the fabrication of small bird-cages, or in weaving a rough kind of mat, or in basket-making. The small nicknacks they turn out are made according to rather ingenious patterns, and partly coloured with red and green vegetable dyes. These, with the skins of animals, and the odoriferous resin collected from the dammer tree, are about the only articles which they barter or sell to the inhabitants of the plains, or to the Mannadis.”

Concerning the religion and superstitions of the Paliyans, the Rev. F. Dahmen writes as follows. “The principal religious ceremony takes place about the beginning of March. Mayāndi (the god) is usually represented by a stone, preferably one to which nature has given some curious shape, the serpent form being especially valued. I said ‘represented,’ for, according to our Paliyans, the stone itself is not the god, who is supposed to live somewhere, they do not exactly know where. The stone that represents him has its shrine at the foot of a tree, or is simply sheltered by a small thatched covering. There, on the appointed day, the Paliyans gather before sunrise. Fire is made in a hole in front of the sacred stone, a fine cock brought in, decapitated amidst the music of horn and drum and the blood made to drip on the fire. The head of the fowl ought to be severed at one blow, as this is a sign of the satisfaction of the god for the past, and of further protection for the future.

Should the head still hang, this would be held a bad omen, foreboding calamities for the year ensuing. The instrument used in this sacred operation is the aruvāl, but the sacrificial aruvāl cannot be used but for this holy purpose. Powers of witchcraft and magic are attributed to the Paliyans by other castes, and probably believed in by themselves. The following device adopted by them to protect themselves from the attacks of wild animals, the panther in particular, may be given as an illustration. Four jackals’ tails are planted in four different spots, chosen so as to include the area within which they wish to be safe from the claws of the brute. This is deemed protection enough: though panthers should enter the magic square, they could do the Paliyans no harm; their mouths are locked.” It is noted by the Rev. F. Dahmen that Paliyans sometimes go on a pilgrimage to the Hindu shrine of Subrahmaniyam at Palni.

Writing concerning the Paliyans who live on the Travancore frontier near Shenkotta, Mr. G. F. D’Penha states11 that they account for their origin by saying that, at some very remote period, an Eluvan took refuge during a famine in the hills, and there took to wife a Palliyar woman, and that the Palliyars are descended from these two. “The Palliyar,” he continues, “is just a shade lower than the Eluvan. He is permitted to enter the houses of Eluvans, Elavanians (betel-growers), and even of Maravars, and in the hills, where the rigour of the social code is relaxed to suit circumstances, the higher castes mentioned will even drink water given by Palliyars, and eat roots cooked by them. The Palliyars regard sylvan deities with great veneration. Kurupuswāmi is the tribe’s tutelary god, and, when a great haul of wild honey is made, offerings are given at some shrine. They pretend to be followers of Siva, and always attend the Adi Amavasai ceremonies at Courtallum. The Palliyar cultivates nothing, not even a sweet potato. He keeps no animal, except a stray dog or two. An axe, a knife, and a pot are all the impedimenta he carries. An [469]expert honey-hunter, he will risk his neck climbing lofty precipices or precipitous cliffs. A species of sago-palm furnishes him with a glairy glutinous fluid on which he thrives, and such small animals as the iguana (Varanus), the tortoise, and the larvae of hives are never-failing luxuries.”

The Paliyans, whom I investigated in North Tinnevelly, were living in the jungles near the base of the mountains, in small isolated communities separated from each other by a distance of several miles. They speak Tamil with a peculiar intonation, which recalls to mind the Irulas. They are wholly illiterate, and only a few can count up to ten. A woman has been known to forget her own name. At a marriage, the father, taking the hand of the bride, and putting it into that of the bridegroom, says “I give this girl to you. Give her roots and leaves, and protect her.” The value of a bride or bridegroom depends very much on the quantity of roots, etc., which he or she can collect. When a widow does not remarry, the males of the community supply her with roots and other products of the jungle. Marriages are, as a rule, contracted within the settlement, and complications occasionally occur owing to the absence of a girl of suitable age for a young man. Indeed, in one settlement I came across two brothers, who had for this reason resorted to the adelphous form of polyandry. It would be interesting to note hereafter if this custom, thus casually introduced, becomes established in the tribe. As an exception to the rule of marriage within the settlement, it was noted that a party of Paliyans had wandered from the Gandamanaikanūr forests to the jungle of Ayanarkoil, and there intermarried with the members of the local tribe, with which they became incorporated. The Paliyans admit members [470]of other castes into their ranks. A case was narrated to me, in which a Maravan cohabited for some time with a Paliya woman, who bore children by him. In this way is the purity of type among the jungle tribes lost as the result of civilisation, and their nasal index reduced from platyrhine to mesorhine dimensions.

The Tinnevelly Paliyans say that Valli, the wife of the god Subramaniya, was a Paliyan woman. As they carry no pollution, they are sometimes employed, in return for food, as night watchmen at the Vaishnavite temple known as Azhagar Koil at the base of the hills. They collect for the Forest Department minor produce in the form of root-bark of Ventilago madraspatana and Anisochilus carnosus, the fruit of Terminalia Chebula (myrabolams), honey, bees-wax, etc., which are handed over to a contractor in exchange for rice, tobacco, betel leaves and nuts, chillies, tamarinds and salt. The food thus earned as wages is supplemented by yams (tubers of Dioscorea) and roots, which are dug up with a digging-stick, and forest fruits. They implicitly obey the contractor, and it was mainly through his influence that I was enabled to interview them, and measure their bodies, in return for a banquet, whereof they partook seated on the grass in two semicircles, the men in front and women in the rear, and eating off teak leaf plates piled high with rice and vegetables.

Though the prodigious mass of food provided was greedily devoured till considerable abdominal distension was visible, dissatisfaction was expressed because it included no meat (mutton), and I had not brought new loin-cloths for them. They laughed, however, when I expressed a hope that they would abandon their dirty cloths, turkey-red turbans and European bead necklaces, and revert to the primitive leafy garment of their forbears. A struggle ensued for [471]the limited supply of sandal paste, with which a group of men smeared their bodies, in imitation of the higher classes, before they were photographed. A feast given to the Paliyans by some missionaries was marred at the outset by the unfortunate circumstance that betel and tobacco were placed by the side of the food, these articles being of evil omen as they are placed in the grave with the dead. A question whether they eat beef produced marked displeasure, and even roused an apathetic old woman to grunt “Your other questions are fair. You have no right to ask that.” If a Paliyan happens to come across the carcase of a cow or buffalo near a stream, it is abandoned, and not approached for a long time. Leather they absolutely refuse to touch, and one of them declined to carry my camera box, because he detected that it had a leather strap.

They make fire with a quartz strike-a-light and steel and the floss of the silk-cotton tree (Bombax malabaricum). They have no means of catching or killing animals, birds, or fish with nets, traps, or weapons, but, if they come across the carcase of a goat or deer in the forest, they will roast and eat it. They catch “vermin” (presumably field rats) by smoking them out of their holes, or digging them out with their digging-sticks. Crabs are caught for eating by children, by letting a string with a piece of cloth tied to the end down the hole, and lifting it out thereof when the crab seizes hold of the cloth with its claws. Of wild beasts they are not afraid, and scare them away by screaming, clapping the hands, and rolling down stones into the valleys. I saw one man, who had been badly mauled by a tiger on the buttock and thigh when he was asleep with his wife and child in a cave. During the dry season they live in natural caves and crevices in rocks, but, if these leak [472]during the rains, they erect a rough shed with the floor raised on poles off the ground, and sloping grass roof, beneath which a fire is kept burning at night, not only for warmth, but also to keep off wild beasts. They are expert at making rapidly improvised shelters at the base of hollow trees by cutting away the wood on one side with a bill-hook. Thus protected, they were quite snug and happy during a heavy shower, while we were miserable amid the drippings from an umbrella and a mango tree.

Savari is a common name among the Tinnevelly Paliyans as among other Tamils. It is said to be a corruption of Xavier, but Savari or Sabari are recognised names of Siva and Parvati. There is a temple called Savarimalayan on the Travancore boundary, whereat the festival takes place at the same time as the festival in honour of St. Xavier among Roman Catholics. The women are very timid in the presence of Europeans, and suffer further from hippophobia; the sight of a horse, which they say is as tall as a mountain, like an elephant, producing a regular stampede into the depths of the jungle. They carry their babies slung in a cloth on the back, and not astride the hips according to the common practice of the plains. The position, in confinement, is to sit on a rock with legs dependent. Many of these Paliyans suffer from jungle fever, as a protection against which they wear a piece of turmeric tied round the neck. The dead are buried, and a stone is placed on the grave, which is never re-visited.

Like other primitive tribes, the Paliyans are short of stature and dolichocephalic, and the archaic type of nose persists in some individuals.

Average height 150.9 cm. Nasal index 83 (max. 100).