Sindh: Education

(Created page with " {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/>You can help by convert...") |

m (Pdewan moved page Sindh, Education: Pakistan to Sindh: Education without leaving a redirect) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Reviewed by Prof Dr Kazi Khadim | Reviewed by Prof Dr Kazi Khadim | ||

| − | [[File: sind.png | |frame|500px]] | + | [[File: sind.png | |frame|500px]] |

| + | |||

| + | [http://dawn.com/ Dawn] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:47, 18 December 2014

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

[edit] Sindh, Education: Pakistan

[edit] REVIEWS: Knowledge of the past

Reviewed by Prof Dr Kazi Khadim

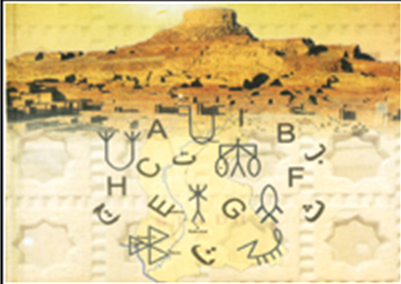

Perhaps the only book written in English about education in Sindh, Dr Habibullah Siddiqui’s anthology discusses education in the historical perspective starting from the ancient system of edification, where education was imparted through pictures, paintings, sculptures, words and symbols carved on stone, wooden and metal utensils belonging to the prehistoric civilisations of Moenjodaro, Kotdiji and Harappa. Though many of the words and symbols found remain undecipherable, they provide sufficient evidence that a written language existed in prehistoric Sindh. This consequently leads to the fact that an education system must have existed at the time.

Having served in the education department and enjoyed various responsible posts, the author has a vast educational background. His eminence not only provided him with access to old records and documents pertaining to basic information about the history of education in Sindh, it has also made possible for him to observe the practical ways and means of the erstwhile education system.

Siddiqui traces the history of education in Sindh from the Islamic period in 712AD, covering various eras from the Soomras, Samas, Arghoons, Tarkhans, Mughals, Kalhoras, Talpurs, and the British to the present times. According to him, during this entire period, Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, English, and the Sindhi language — alphabets of which were put together during the British rule — were the mediums of instruction. Even today, Arabic and sometimes Persian language is used as a mode of communication in local madressahs of Sindh.

Education in Sindh: Past and Present is divided into 10 chapters. The chapter titled ‘The educational tradition’ comprises information about the cultures of Kotdiji, the Indus civilisation, the Aryan invasion and the Vedic period, and emphasises on the indigenous traditional maxims in the Sindhi language. The following chapter discusses the ancient system of education, also dealing with the Brahamanic and Buddhist systems. It focuses on the Persian and Greek invasions and how their remnants effected the language and culture of the area.

The Islamic system of education has also been discussed thoroughly in the book including everything from Quranic injunctions and the role of mosques and madressahs in imparting Islamic education, to the various methods of teaching used. ‘Education during the local rule of Soomras and Samas’ is another interesting chapter dealing with the promotion of the Sindhi language and contributions made by the Ismaili missionaries in the development of the language as well as the education sector of those times. This era also witnessed the advent of Sufism and major developments in the Sindhi language.

The book also discusses the system of education during the alien rule of the Arghoon, Tarkhan and the Mughals as well as during the local rule of the Kalhoras and Talpurs. These chapters deal with the decline, devastation and loss of records in the Kalhora period and the rise in the respect for the learned and the position of the Persian language. Moreover, the author also provides an introduction to the expansion of the western educational system under the British rule and emphasises on how the indigenous Islamic system of education survived the British rule. The final chapter, ‘Education in Sindh’, is divided into three parts which deal with educational developments and policies.

The concluding part, a valuable addition to this study, is spread over some 226 pages. It adds to making this book an undoubtedly a priceless research work in the field of education, providing the reader with authentic information on the subject.

Education in Sindh: Past and Present By Dr Habibullah Siddiqui Institute of Sindhology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro sindhology_s@yahoo.com ISBN 969-405-079-0 625pp. Rs500

[edit] Sindh, Education, literacy, women

Against all odds

By Zofeen Ebrahim

Shumaila is sitting for her school certificate exam this month. But that does not relieve her from daily chores that include tending to dozen or so head of cattle. I spend Sundays doing the washing for the entire family piled up over the week, said the 15-year-old, speaking with this scribe at her home in the Khora village of Khairpur district, about 450km north of this port city.

Because the girls' school she attends does not extend beyond grade eight, she and six other girls had to join the government boys' secondary school to appear for their grade nine and 10 exams.

The only free time Shumaila and her classmates get is in the night, which they feverishly put to use to study, literally burning the midnight oil as there is no electricity.

"But we don't mind the housework, and it's really no burden. It doesn't matter because unlike so many others we know, we're lucky to have been given the opportunity to study," says her friend Sadaf.

This year, the Indus Resource Centre (IRC), which set up her school will be celebrating a huge success. A total of 26 girl students from various schools run by the non-governmental organisation (NGO) will be sitting for their matriculation (grade 10) with hopes of moving on to college.

"I know this is just a drop in the ocean, but I feel energised when I see how motivated these girls are. I know we have funding constraints but we will support each one of them," says Sadiqa Salahuddin, IRC's director. ‘'They have proved by their brilliant grade nine results that they deserve our help. Except for a couple, all got ‘A' grades." She is banking on "philanthropists here who will readily help these girls through college".

What moves Salahuddin is how much effort these girls have to put in to ensure they are not removed from school. "Despite attending to household chores, work in fields, tending to livestock, baby-sitting for younger siblings, they remain eager to come to school and focus on studies," she marvels.

"Our exams will be over just before the cotton-picking season starts," says Shamshad, counting her blessings.

According to a new report titled EFA: A Critical Review of Policies, Implementation and Quality of Education, by the Sindh Education Foundation (SEF), there are 45,000 schools in Sindh province of which 7,734 are for girls, 19,917 for boys and 16,987 are co-educational. Some 7,442 are ghost schools (those which are only on paper and where the funds allocated to them are being used by non-attending teachers and staff) in Sindh.

Low spending on education and health is a leading contributor to the country's low ranking in the United Nations Human Development Index at 142 out of 177 countries.

Without a quantum leap, Pakistan will remain among the 26 countries that will fail to meet the UN prescribed millennium development goals (MDGs) of achieving universal primary education by 2015. Of a total of 6.5 million girls of school-going age, 4.2 million still remain out of school despite Pakistan being a signatory to Unesco's Education For All (EFA) goal set for 2015. The drive to achieve the EFA goal contributes to the MDGs -- especially MDG 2 on universal primary education and MDG 3 on gender equality in education, by 2015.

However, Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf's promise of jacking up the budget for education to four per cent earlier this year has been ruled out by the finance ministry.

"There is no fiscal space available to make such a huge increase in the next budget for education sector," reported an English daily, adding that there could, at best, be an increase of 0.3 to 0.5 per cent.

But this increase would be put into construction of facilities and recruitment of teachers without any effort going into improving quality of education.

For the girls, IRC provides scholarships to take care of tuition fees, transport, stationery, and books. "We spend between Rs7,000 to Rs8,000 ($117-133) on each child annually, but if you ask me, every rupee is worth it," says Salahuddin.

Over the years the IRC has seen a sea change in community perception towards girls' education. "Many parents realise that even if education does not guarantee jobs for their daughters, it makes them better wives and mothers," says Salahuddin. ‘'It is just a myth that parents don't want to send their daughters to school. Most realise that investing in girls' education is a route to a better future.

However, at times they come across parents who feel letting their children go to school means losing out on helping hands. "That is a genuine problem as girls not only help with household chores, but take care of siblings while both the parents are out in the fields. And when these girls are a little older, then the burden of work is increased to include tending to animals as well as lending a hand in the fields," says Salahuddin.

Furthermore, non-availability of middle and secondary schools proves to be a deterrent for parents.

Of late, parents have also realised that there are jobs in rural areas that require educated females. ‘'Female teachers are sought after, as are lady health workers, to give two good examples – and these need a minimum educational qualification of tenth grade."

"There are gaps in the schooling of our teachers," concedes Salahuddin, adding: "We have to teach them not only how to teach but also content. It is a painfully slow process." All the primary school IRC teachers are females and if there is no matriculate (a minimum requirement), they manage to find one from a nearby village and provide her with transport.

"This is a very important issue as we've realised that parents don't consider it worthwhile to send their children to school, be they boys or girls, if they are not learning anything," says Salahuddin. "We have to ensure that we are delivering quality otherwise all our efforts will be in vain."

Yet another problem the IRC faces is convincing parents of these young teachers to allow them to go for residential training which means a few days away from home. ‘'Sometimes we have to accommodate a mother, siblings and maybe even an aunt in order to train one teacher." — Dawn/IPS News Service