Apur Sansar (1959)

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

[[Category: Cinema-Tv-Pop|R]] | [[Category: Cinema-Tv-Pop|R]] | ||

[[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | [[Category:Name|Alphabet]] | ||

| + | |||

=Apur Sansar (1959): A Synopsis= | =Apur Sansar (1959): A Synopsis= | ||

Friday, December 11, 2009 | Friday, December 11, 2009 | ||

Revision as of 19:49, 28 June 2013

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Apur Sansar (1959): A Synopsis

Friday, December 11, 2009

Apur Sansar ( 1959 ) The World of Apu

Satyajit Ray* 110 minutes*

An impoverished Apu ( Soumitra Chatterjee ) is now somewhere in his twenties, rent dodging, job seeking, dreaming of making a living out of his literary talent, hoping to avoid a soul destroying occupation. The camera roves over the smoky, misty, noisy, crowded Calcutta-scape to the accompaniment of Ravi Shankar's perfect musical accompaniment and I could not avoid the pangs of nostalgia for a less complicated and more friendly world that seems to have passed by. How lovingly the landlord demands arrears of rent! No room for stereotypes ! Ray's world is overwhelmingly good natured ( a kind of Bangla Malgudi, to draw a far fetched comparison ). Ray was confessedly a man of the city, and his rural knowledge is acquired. He breathes poetry into whatever he touches and this final installment is a worthy conclusion, as he leaves an open future to his creations as the film concludes.

We see the family in the processes of an Indian marriage turning sour mid-way. The joyous wail of the shehnai is abruptly interrupted. The dignified and shy bride ( Sharmila Tagore) is cast into the midstream of life's cross-currents, her fortunes as uncertain as a cast of die. People who say Ray's cinema is slow don't know what they are talking about. There may not be motion of objects at velocity but the development of events which shape people's lives is always swift and the tension never slackens, hardly for a moment. In these unhurried and contemplative rhythms, he is able to encompass the extremeties of birth and death. The moments of trauma are captured imaginatively like the son hurling a big stone at his father or Apu when he hits his brother in law. This is as violent as it ever gets in the trilogy.

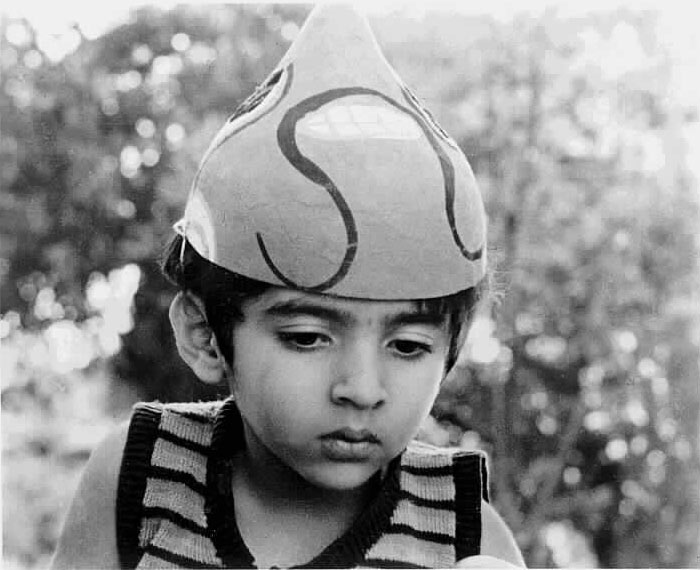

The concluding part of the film --the first encounter of the absconding father with his five year child-- is cinema of rare emotional sensitivity which never descends to the expected or stereotyped. Ray is able to enter the mind of children, the wonder as well as the terror and heartache, like few others. The demon-mask with which the child is introduced is an apt metaphor of the tumult within a rejected child. It is Apu the Second! One could write a great deal about this last segment, whose meticulous crafting, deserves to be put under an appreciative microscope.