Emergency (1975-77): India

(→AICC meet post Emergency) |

(→AICC meet post Emergency) |

||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

The Chandigarh AICC session was also the one where Sanjay Gandhi’s star was on the ascendant, while the meet reaffirmed postponement of elections; continuation of the emergency and the inevitability of constitutional changes. The “foreign hand” theory was in full play, with long anti-CIA tirades by the members. | The Chandigarh AICC session was also the one where Sanjay Gandhi’s star was on the ascendant, while the meet reaffirmed postponement of elections; continuation of the emergency and the inevitability of constitutional changes. The “foreign hand” theory was in full play, with long anti-CIA tirades by the members. | ||

The Embassy observed, “It was clear she was referring to the US, Pakistan, China and the rich nations” of the world as sponsors of these “external dangers”. Internal “dangers” were the foreign press, the DMK government in Tamil Nadu, the Janata front government in Gujarat, etc. “No other speaker surpassed her forcefulness.” | The Embassy observed, “It was clear she was referring to the US, Pakistan, China and the rich nations” of the world as sponsors of these “external dangers”. Internal “dangers” were the foreign press, the DMK government in Tamil Nadu, the Janata front government in Gujarat, etc. “No other speaker surpassed her forcefulness.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Forced sterilisations= | ||

| + | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com//Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=40-YRS-OF-EMERGENCY-Nasbandi-with-handcuffs-on-21062015022017 ''The Times of India''], Jun 21 2015 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Avijit Ghosh in Uttawar, Haryana | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' A tale of two villages that saw the ugliest face of the Emergency ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Emergency meant different things to different people. For editors it was a daily battle with censorship. | ||

| + | For politicians, barring Congressmen and some Leftists, it was time to go underground or to jail. For cops it meant absolute authority , thanks to the dreaded ordinance, MISA (Maintainence of Internal Security Act). | ||

| + | |||

| + | But for Uttawar village, 60 km south of Delhi, the Emergency will always be about one unnerving morn ing in the bitter winter of 1976 when hundreds from the Muslim-dominated village were packed into buses and taken to police stations, where they were thrashed, jailed and forcibly sterilized. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If the 1975 Emergency was a black mark on India's democratic register, forcible sterilization was its ugliest public face. And two Haryana villages, Uttawar and Pipli, lived its horror.The drive stemmed from the wisdom that parivar niyojan or family planning was imperative to prevent population explosion. But the implementation had communal undertones too. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now part of rejigged Haryana's Palwal district, Uttawar is in Mewat region largely inhabited by Meo Muslims. Many are marginal farmers or daily wagers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Uttawar had substantial Congress voters but the Emergency turned them against the No. 1 national party .In the 1977 Lok Sabha polls, the entire village voted for Janata Party. | ||

=2015: 40th anniversary= | =2015: 40th anniversary= | ||

Revision as of 14:43, 22 June 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

SS Ray led Indira into Emergency

Pranab Mukherjee, December 12, 2014

The 1975 Emergency was perhaps an “avoidable event” and Congress and Indira Gandhi had to pay a heavy price for this “misadventure” as suspension of fundamental rights and political activity, large scale arrests and press censorship adversely affected people, says President Pranab Mukherjee. A junior minister under Gandhi in those turbulent times, Mukherjee however, is also unsparing of the opposition then under the leadership of the late Jayaprakash Narayan, JP , whose movement appeared to him to be “directionless”. The President has penned his thoughts about the tumultuous period in India's post-independence history in his book “The Dramatic Decade: the Indira Gandhi Years” that has just been released.

He discloses that Indira Gandhi was not aware of the Constitutional provisions allowing for declaration of Emergency that was imposed in 1975 and it was Siddartha Shankar Ray who led her into the decision.

Ironically, it was Ray, then Chief Minister of West Bengal, who also took a sharp aboutturn on the authorship of the Emergency before the Shah Commission that went into `excesses' during that period and disowned that decision, according to Mukherjee.

Mukherjee, who celebrated his 79th birthday on Thursday, says,“The Dramatic Decade is the first of a trilogy; this book covers the period between 1969 and 1980...I intent to deal with the period between 1980 and 1998 in volume II, and the period between 1998 and 2012, which marked the end of my active political career, in volume III.“

“At this point in the book, it will be sufficient to say here that many of us who were part of the Union Cabinet at that time (I was a junior minister) did not then understand its deep and far reaching impact.“

Mukherjee's 321-page book covers various chapters including the liberation of Bangladesh, JP's offensive, the defeat in the 1977 elections, split in Congress and return to power in 1980 and after.

“ The Dramatic Decade: The Indira Years”: Pranab Mukherjee

Harish Khare

January 9, 2015

The partisan in Pranab Mukherjee omits crucial details about the Emergency but the politician in him offers a blue book on recouping political fortunes after a defeat.

The Dramatic Decade

The Indira Gandhi Years by Pranab Mukherjee, he has given us a fascinating history of a turbulent period in the journey of our young nation-state. Apart from two possible exceptions- L.K. Advani and Sharad Pawar-no other active political leader is well equipped as Mukherjee is to throw light on a period that saw the rise, fall and rise, again, of Indira Gandhi.

Mukherjee had been a Mr Minister for almost four decades before he became Mr President. He is a natural when it comes to exercising power and authority in the interests of the nation. Now he has given us a peep into his thoughts and calculations as he became Indira's partisan. It makes for an absorbing read.

There are, however, two glaring-and disappointing-omissions. Mukherjee has made Sanjay Gandhi, the catalyst for the political turbulence, an almost non-person; Indira's younger son's role-before, during and after the Emergency-is referred to only in passing, almost as if he were a minor figure, rather than one of the prime movers, if not the prime mover. This is at variance with all other historical accounts; it would have been useful if Mukherjee had tried to explain whether or not Sanjay's culpability was overstated by the Congress's rivals. Instead, there is a hint or two to suggest that Mukherjee was not uncomfortable with Sanjay's presence and role. There is even admiration at the spunk and spirit that Sanjay displayed in standing up to the Janata Party bullies: "It also became clear that his boys would never leave him and, in times to come, Sanjay Gandhi's boys became the cornerstone of our new movement."

A related glaring omission is the virtual absence of any discussion of the "excesses" of Emergency, which Mukherjee calls a "misadventure". For instance, he mentions that "during the Emergency, a large number of judges had been transferred to other High Courts, so much so that in one instance sixteen judges had been transferred on a single day". Yet there is no suggestion as to who had instigated it. It would have been useful to have his reflections on why these "excesses" took place. He, though, makes a loaded observation: "Interestingly, though not surprisingly, once it was declared, there was a whole host of people claiming authorship of the idea of declaring of Emergency. And, again, not surprisingly, these very people took a sharp about-turn when the Shah Commission was set up to look into the Emergency 'excesses'." Mukherjee is indeed drawing attention to a quintessential Indian democratic conundrum, which we have not yet fully confronted. There is a great yearning for a strong, vigorous executive political authority-yet without its inherent potential for over-zeal and abuse. Perhaps this has something to do with our collective gift for duplicity. Though rhetorically the country has come to abhor the Sanjay Gandhi phenomenon, it remains tantalisingly fascinated with Sanjay Gandhi-like political options.

In the context of the JP movement, Mukherjee draws attention to another democratic dilemma: "which democracy in the world would permit a change of popularly and freely elected government through means other than a popular election? Can parties beaten at the hustings replace a popularly elected government by sheer agitations?" These questions remain valid. We were confronted with a similar painful choice when the Anna Hazare platform was used to make peremptory claims in the name of the Janata.

Mukherjee's book serves another purpose. It makes us think about a slogan of which we have become very fond-the curative potency of "willpower". A student of political economy is left dissatisfied because Mukherjee does not explain why it was not possible for Indira's government-with all the requisite accruements of "willpower", a strong leader, political clarity, a decisive parliamentary majority, a cabinet full of first-class talent-to get on top of the 1973-75 economic crisis.

He does quote C. Subramaniam's 1975-76 budget speech to own up that "we have been ill-equipped to withstand" the impact of virulent global economic forces. These were pre-globalisation days. Since then national economies have become much more interdependent, though we persist in believing that a "strong leader" can solve intractable economic problems by sheer political will.

Mukherjee has alluded to some of these significant political propositions that keep on impinging upon the polity. However, the most enjoyable chunks of the book deal with the turmoil in the Congress. Throughout, Mukherjee remains an Indira loyalist, partisan and admirer.

He gives us a flavour of the 1969 split-how the polity, operated as it mostly was by the Congress bosses, had become dysfunctional and how it was Indira's historic task to initiate a series of moves that would help the "system" break out of the politically created logjam. This also created scope for institutional stand-off. The higher judiciary was not inclined to see the need for change, leave alone see any institutional role for itself in the management of that change. The result was, as Mukherjee puts it, a "strained relationship" between the executive and the judiciary-a subdued confrontation that was to later cost Indira dearly.

Mukherjee has done well to reproduce a letter Indira wrote-a few days after Pakistan's surrender at Dacca-to the chief justice of India. In a masterly formulation, she asks the chief justice to appreciate the need to look beyond the comforting stability of status quo: "... As our nation moves forward and our society gains inner cohesion and sense of direction all our great institutions, Parliament, Judiciary and Executive, will reflect the organic unity of our society.

Legal stability depends as much upon the power to look forward for necessary adjustment and adaptation as to look backward for certainty." And then she makes a telling point: "... Needs and grievances of the people in a democracy cannot be met by repression of their manifestation but by remedying the causes which underline them." Indira was riding high; the judiciary waited for her political fortunes to suffer a decline before settling a score or two with her.

When, after the 1977 defeat, the time came to choose sides, Mukherjee had no doubt or hesitation; he stood by Indira: "everybody knew of my affiliation, and I did not give them reason to believe otherwise till the day she died." No ambiguity there. And when the factional lines got redrawn, Mukherjee enjoyed the role of a factionalist: "I was then working with A.P. Sharma, C.M. Stephen, R. Gundu Rao and Vasant Sathe, and we took an active role against (D.) Barooah. We usually moved in a group and took direction from Kamalapati Tripathi and Indira Gandhi herself." As an Indira loyalist, he knew his tactics. He writes: "I knew there was no way out except to resort to a show of strength." And, again, a few pages later: "(A.R.) Antulay and I were all for the split. We were sure that the Congress could not be revived without a split." Mukherjee's account offers many clues and suggestions on how to recoup political fortunes after an electoral defeat. It is almost a blue book on how to create or take over a political party.

Indira wanted to tax farm income: 1975

From the archives of The Times of India

April 10, 2013

Indira Gandhi was willing to go where politicians today fear to tread. Back in 1975, she wanted to tax agriculture income and the rural rich. It remains a no-go area for policymakers even today. Addressing the Institute for Social and Economic Change in Bangalore, which was reported by the US mission in India, revealed by WikiLeaks, she reportedly asked the states “to overcome the compulsions that have stopped them from taxing agriculture income and the rural wealthy. She particularly deplored subsidies on water and power used for irrigation. She warned the states they would not receive any overdrafts if they overspent.” While these might sound free-market thinking, Gandhi took a different stance by saying `the "income tax department is being asked to intensify its efforts to bring self-employed professionals and traders within the tax net,’ without indicating how this was to be done.” She also warned industrial borrowers that they were being watched closely, justifying the credit squeeze on the private sector.

Fakruddin Ali Ahmed resented Indira

From the archives of The Times of India

April 10, 2013

Fakruddin Ali Ahmed, the rubber stamp President during the Emergency era, may not have been a complete rubber stamp after all. According to a US embassy cable sent on August 6, 1976, the mission said, “We have heard much more reliably (than rumours) that Fakruddin is seriously concerned over the govt’s family planning moves.” The cable said the rumours have been about “some disaffection between the Prime Minister and President Fakruddin Ali Ahmed. The stories vary but have as their central core that Fakruddin is concerned that the PM and her son are pushing too hard on the political and constitutional system of India.”

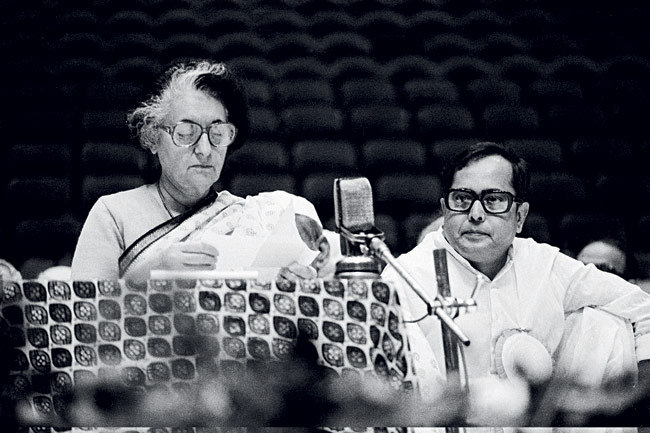

AICC meet post Emergency

From the archives of The Times of India

April 12, 2013

New Delhi: The first AICC session after imposition of Emergency was an ‘Indira Gandhi’ exercise, with then Congress president, D K Barooah (of India-is-Indira fame), comparing her to emperor Ashoka and Mahatma Gandhi rolled into one.

The US embassy in India, reporting on the event (as revealed by Wikileaks), said the Chandigarh session “underscored Mrs Gandhi's overriding political position and enhanced authoritarianism in India. There was no dissent. For the first time, no amendments were even considered to the resolutions that were drawn up by the CWC drafting committee of which the Prime Minister was a member.” Under heavy security, all the speakers sang paeans to Gandhi and all were her loyalists. Everybody rationalized the Emergency. “Mrs Gandhi in several emotional speeches charged that external and internal conspiracies aimed at undermining India's unity were still at work.” In other cables describing the political situation, US diplomats observed that there was apparent calm though press censorship suppressed all news or protests. Another cable said the average Indian citizen seemed unaware or unconcerned about the Emergency. Yet another cable described how Mrs Gandhi was able to craft her foreign policy more “evenly” in the absence of political opposition. The Chandigarh AICC session was also the one where Sanjay Gandhi’s star was on the ascendant, while the meet reaffirmed postponement of elections; continuation of the emergency and the inevitability of constitutional changes. The “foreign hand” theory was in full play, with long anti-CIA tirades by the members. The Embassy observed, “It was clear she was referring to the US, Pakistan, China and the rich nations” of the world as sponsors of these “external dangers”. Internal “dangers” were the foreign press, the DMK government in Tamil Nadu, the Janata front government in Gujarat, etc. “No other speaker surpassed her forcefulness.”

Forced sterilisations

The Times of India, Jun 21 2015

Avijit Ghosh in Uttawar, Haryana

A tale of two villages that saw the ugliest face of the Emergency

The Emergency meant different things to different people. For editors it was a daily battle with censorship. For politicians, barring Congressmen and some Leftists, it was time to go underground or to jail. For cops it meant absolute authority , thanks to the dreaded ordinance, MISA (Maintainence of Internal Security Act).

But for Uttawar village, 60 km south of Delhi, the Emergency will always be about one unnerving morn ing in the bitter winter of 1976 when hundreds from the Muslim-dominated village were packed into buses and taken to police stations, where they were thrashed, jailed and forcibly sterilized.

If the 1975 Emergency was a black mark on India's democratic register, forcible sterilization was its ugliest public face. And two Haryana villages, Uttawar and Pipli, lived its horror.The drive stemmed from the wisdom that parivar niyojan or family planning was imperative to prevent population explosion. But the implementation had communal undertones too.

Now part of rejigged Haryana's Palwal district, Uttawar is in Mewat region largely inhabited by Meo Muslims. Many are marginal farmers or daily wagers.

Uttawar had substantial Congress voters but the Emergency turned them against the No. 1 national party .In the 1977 Lok Sabha polls, the entire village voted for Janata Party.

2015: 40th anniversary

The Times of India, Jun 21 2015

Patrick Clibbens

Emergency wasn't just about Sanjay and his playground

Forty years, on the night of June 25, 1975, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared that India was in a state of `grave emergency'. Although the government had declared emergencies twice before (indeed the 1971 emergency was still in place), they had been in times of war. In 1975, the government was targeting events within India itself -the `internal disturbance' that it claimed threatened the security of India.

The government's crackdown transformed Indian political life. Yet for many people today , the Emergency is best remembered for its twin social programmes of urban clearances and mass sterilizations.The government pursued them on a massive scale. Almost 11,000,000 people were sterilized in just two years, while 700,000 had their homes or businesses demolished in Delhi alone.

When describing the Emergency , historians have relied on one document more than any other: the three-volume Shah Commission report published in 1978. Justice J C Shah oversaw a fact-finding team which gathered thousands of documents and testimonies. For years the report was hard to trace, with copies languishing in a few uni versity libraries, but since its republication by Era Sezhiyan this crucial document is readily available in India. It is the source of much of our knowledge about the Emergency , but its own blind spots and unspoken assumptions are the origin of many common misconceptions today .

When the Shah Commission was appointed in May 1977, the new Janata government instructed it to inquire into the `excesses' committed during the Emergency -this terminology implied that the Emergency consisted of good policies pursued with too much zeal.The report also assumes a `drastic change after the Emergency', and the idea that it was a short-term aberration was built into the Commission's inquiries. More extensive historical research shows that, at least for the highly emotive social programmes, we must qualify this view.

In the Emergency family planning programme, New Delhi set targets cascading from the central departments out through states to the most junior local officials. The programme created tissues of targets, incentives and disincentives disproportionately directed at the poor and those reliant on government jobs, housing or welfare. All these features predated the Emergency . For example, since 1959 the State of Madras (now Tamil Nadu) had given `canvassers' a cash payment for each man they brought to be sterilized, though they knew the canvassers often misled patients. Mahar ashtra had used a package of `disincentives' to pressure people since 1967, while Kerala had pio neered `massive vasectomy camps' which sterilized thousands at a time in the early 1970s.

Another feature of the Shah Commission's re port which has often figured in discussions of the Emergency is its focus on a few personalities, par ticularly Indira Gandhi's younger son, Sanjay .

Justice Shah naturally wanted to pin down those responsible for the abuses he had documented and it is clear that Sanjay liked to issue instructions to ministers despite having no government position of any kind. Yet identifying Emergency policies so closely with one man means we risk losing sight of other actors.

In particular, regarding Sanjay as the `evil genius' of the whole demolition programme has focused all the attention on Delhi and its environs, as this was Sanjay's playground. Justice Shah dedicated 63 pages to demolitions in Delhi, but covered the rest of the country in 10 pages without providing any statistics. Some large states were neglected entirely . More recently , the influential account by Indira Gandhi's secretary P N Dhar also states that demolitions took place in Delhi, Haryana and western UP `in order to please Sanjay Gandhi'. UP `in order to please Sanjay Gandhi'.

Yet if we take just one example -Mumbai -we can see that this focus is misleading. During the Emergency , the city finally succeeded in demolishing the dwellings of over 70,000 people from the Janata Colony and transported them to the deso late, marshy land at the tip of Trombay . Beggars were also a target: thousands were rounded up and transported to a holding camp in a cattle shed and then to `work camps' 160km inland, where they were also sterilized.

In this anniversary year, we will no doubt hear more about the high politics and drama of the Emergency . Yet there is so much we still don't know about the many different ways in which people across India experienced the Emergency in their everyday lives. The Shah Commission has served us well, but it's time to get researching.