Neerja Bhanot

(→in the highjacked airccraft) |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Soon after, when Pan Am decided to have an all-India crew to cater to its Asian clients — other than Air India, it was the first airline to do so — Neerja applied for the job. | Soon after, when Pan Am decided to have an all-India crew to cater to its Asian clients — other than Air India, it was the first airline to do so — Neerja applied for the job. | ||

| − | = | + | =In the highjacked airccraft= |

'''5.25 am, September 5, 1986''' : The Pan Am 73 flight from Mumbai to Frankfurt landed at the Jinnah International Airport, Karachi, for an hour-long stopover. | '''5.25 am, September 5, 1986''' : The Pan Am 73 flight from Mumbai to Frankfurt landed at the Jinnah International Airport, Karachi, for an hour-long stopover. | ||

Four heavily-armed Palestinian men, belonging to the Abu Nidal Organisation, hijacked the aircraft carrying 360 passengers, many of them Americans. | Four heavily-armed Palestinian men, belonging to the Abu Nidal Organisation, hijacked the aircraft carrying 360 passengers, many of them Americans. | ||

Latest revision as of 19:09, 21 February 2016

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

[edit] Early life

The Indian Express, February 21, 2016

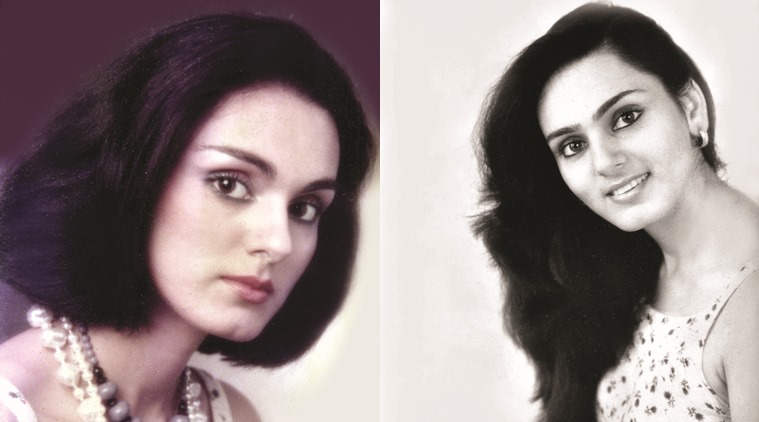

The Bhanots moved to Bombay in March 1974. They lived in Patrakar Colony, Bandra East, and Neerja was admitted to the prestigious Bombay Scottish High School, Mahim. She spent her formative years in the city that shaped her life and career. Here, she found her own circle of friends, while her brothers continued to study in Chandigarh till they graduated. When Neerja joined Bombay Scottish in Class VI, she was a quiet girl with two long plaits. “Once she chopped them off and got a blunt cut, we were struck by how beautiful she looked,” says Eliza Lewis, her classmate, 53, who dubs English films in Hindi. In the years to come, that hairstyle would become her signature look. An average student, Neerja was good at many sports, including throwball, gymnastics and basketball. “She was a loyal friend. Even if we had a disagreement, she would always be the first one to reach out,” says Vrindra Kriloskar, 53, who became friends with Neerja when they were Class VIII students in Bombay Scottish. Lewis remembers Neerja as fearless and honest. “If she had not done anything wrong, she would never cower when the teachers got angry. She would speak her mind, tell them the truth,” she says. Kirloskar recalls the inherent impishness in her. “She had her share of admirers. If she caught someone staring at her, she would walk up to him and wave at him, just for fun,” she says. Neerja was in school when Akhil had started working for an ad agency and amassed a huge collection of LP records. Kirloskar recalls that they were allowed to play the records provided they put them back in the stack. They sung along to Duran Duran, ABBA, Boney M, Michael Jackson and Madonna numbers. “We used to sneak in to matinee shows at Sterling which is close to Xavier’s College as we could return home before evening,” says Kirloskar. The first English movie they watched in a theatre was The Godfather (1972) when they were in Class VIII. “There was so much talk about it that we had to watch it. We were young but had older brothers to accompany us to the theatre. And as expected, we did not understand the dialogues,” she says.

Neerja wanted to excel in whatever she was doing. Yet, Kirloskar can’t recollect any overriding career ambition that Neerja nursed till she stumbled into modelling. She was 18 then. One afternoon, the two friends were munching on roasted bhutta outside the college campus when a photographer approached Neerja. He wished to feature her in a section called ‘The girl next door’ in the magazine Bombay.

Once the photo was printed, she got her first modelling offer. Paville, a popular retail store, had contacted her. “If she was nervous, she never showed it. After the photoshoot, we spent the whole day giggling about the proprietor’s clipped accent and the way she had held her cigarette,” says Kirloskar, who accompanied her for the photoshoot. In the black-and-white ad, she is striding confidently down the road, with her head thrown back and smiling.

Over the next four years, Neerja modelled for various brands. Those who owned a television in the 1980s will remember her walking, arms wrapped around herself, on a winter afternoon in an ad for Charmis cold cream; as a bride bickering with the groom over the taste of Krack Jack biscuits; and as a mother rewarding her son with an Amul chocolate. She also appeared in print ads for several baby products, for retail stores such as Benzer and Chirag Din, apart from gracing the covers of magazines like Manorama.

“We were not very career-minded while growing up even though we had classmates who had planed to study medicine or engineering,” says Lewis, who joined an ad production house as assistant director when she was 23. The number of women in media were still few. Yet, women professionals returning home late was not uncommon. Ad filmmaker Ayesha Sayani — who directed the commercial for a baby product, the last one Neerja shot before boarding the fateful flight — says: “I was not a hard-nosed professional. However, after my divorce, I wanted to bring my daughter up by myself. I faced some initial objections which disappeared eventually.”

“Our parents never stopped her from modelling. She had their approval as long as it was not for liquor or some such brand,” says Aneesh. Working in ads gave her financial independence and an opportunity to indulge her sense of style. “When I met the owner of a shoe store in Oberoi Hotel’s shopping arcade after her death, he told me that they used to call Neerja a ‘princess’ because she never haggled over the price of a pair of shoes she liked,” says Aneesh.

[edit] Personal Life

The Indian Express, February 21, 2016

Before she stood up to a gang of hijackers on a Pan American World Airways flight, Neerja Bhanot’s major act of courage was to walk out of her marriage.

It was 1986. She was a 21-year-old in Bombay, a striking young woman with a modelling career that was just taking off. That she had agreed to a match arranged by her father to a man based in Sharjah had come as a surprise to many. She was the sherni of the family, a fiercely independent young woman. But, devoted as she was to her father, Neerja could not say no. In Sharjah, the marriage nosedived. She was harassed by demands for dowry, starved and denied any money. A few months later, by the time she returned to her Bandra home to wrap up a modelling assignment, she had lost 5 kg. Her husband’s letter followed, listing out the conditions she was expected to follow: it included “respecting” him and severing ties with her own family. What cut her to the bone, recalls her brother Aneesh, was the question: “What are you? You are a mere graduate.” Neerja decided to end the marriage. The first person she confided in was her father, journalist Harish Bhanot. When the family assembled in the dining room, Harish announced that Neerja did not wish to return. They agreed. Once she knew that her family supported her decision, Neerja never looked back. She wrote a letter to her father, thanking him for his support and promising that she would make him proud.

Soon after, when Pan Am decided to have an all-India crew to cater to its Asian clients — other than Air India, it was the first airline to do so — Neerja applied for the job.

[edit] In the highjacked airccraft

5.25 am, September 5, 1986 : The Pan Am 73 flight from Mumbai to Frankfurt landed at the Jinnah International Airport, Karachi, for an hour-long stopover. Four heavily-armed Palestinian men, belonging to the Abu Nidal Organisation, hijacked the aircraft carrying 360 passengers, many of them Americans. They grabbed Neerja, who was at the entrance to welcome the passengers, by her hair. Sensing danger, she conveyed the “hijack code” over the intercom to the flight’s cockpit crew. Soon, the cockpit crew — pilot, co-pilot and flight engineer — escaped through the cockpit’s emergency hatch. Being the purser, Neerja became the head of the flight even though she had started flying only six months ago. For 17 hours, Neerja and other members of the crew did their best to take care of the passengers and calm them down. She protected the Americans on board, who were targeted by the hijackers, by hiding their passports under a seat. At 9.55 pm, when the flight’s auxiliary power unit ran out of fuel, plunging the aircraft into darkness, the hijackers went on a shooting spree. Neerja and a passenger flung open two emergency doors, allowing many passengers to escape. While helping three children slide down the chute of the emergency exit, Neerja was hit by bullets. Though she was rescued by two of her colleagues, she died before any medical assistance could reach her. She was one of 23 casualties. Heroes don’t belong to a different breed. This is true of Neerja — described by most as “an ordinary girl with an extraordinary spirit”. Both director Ram Madhvani and producer Atul Kasbekar, who have teamed up to make a film on the courageous young woman, felt that her “inspirational” story should be back in the spotlight. Neerja was born on September 7, 1962, in Chandigarh Sector 16 where her father Harish worked as a journalist with Hindustan Times. In a piece he wrote for his paper soon after her death, Harish recounts that when a nurse from the maternity ward rang him up to say that his wife had given birth to a baby girl, he conveyed his “double thanks” to her. Not used to the birth of a girl being celebrated, she repeated herself: “It is a daughter”. The ecstatic father made it clear that they had wished for a daughter. They already had two sons — Akhil, 8, and Aneesh, 5. She was fondly called Lado (the loved one) and became the centre of the family’s affections. Growing up with her brothers, she had a hearty outdoor life, playing pittu and cricket. But being the youngest meant she was bullied too. They would make her run errands for them. After spending their weekly pocket money of Rs 2, they would cajole her into buying them ice cream from her share. Often, Aneesh and she would go to the market to buy milk. On the way back, the fight used to be over who would get to eat the layer of malai. When their parents got to know what the brothers were up to, they would get an earful. “Ours is a different household. Girls always enjoyed more affection. Even today, Rohini, Akhil’s daughter, gets more attention than her brother,” says Aneesh.

In the 1980s, women were cherry-picked for the job of an air hostess, which embodied glamour and a certain social status. Minna Vohra, daughter of an army officer who was selected from Delhi for the first batch of Pan Am airhostesses, says the selectors scouted for convent-educated girls, with a good height and a striking appearance. At 5 feet and 9 inches, and with a smile that launched several brands, Neerja fit the bill. “Getting a job in an international airlines was considered to be a big deal,” says Vohra. Out of the 10,000 applicants, Neerja was one of 80 candidates chosen for the job; there were nearly 50 women from Mumbai and the rest from Delhi. While others struggled to do their make-up and hair, thanks to her modelling background, she was at ease with these tasks. “From my interactions with her I remember her not being much of an extrovert. But we did have a blast when we went out together,” says Vohra. After nearly 6-8 weeks of training in Miami, Neerja was sent to London to be trained as a purser with 12 others. They were selected on the basis of their performance during examinations, briefings and emergency procedures. Peer evaluations were taken into consideration too. The task of making announcements, allocating seats and placating irate passengers often fell on pursers, who worked as troubleshooters-cum-managers on flights. “Even though they had to learn about wine and cheese, the emphasis of the training was on security and safely measures,” says Vohra. Neerja’s roommate during the Pan Am training days was Rukhsana Eisa, who is a Mumbai-based celebrity grooming and etiquette coach today. The Pan Am flight crew, which flew twice a week, would work 18 hours at a stretch. The perks were many: they were off work the rest of the week; they had access to unlimited free air tickets. “This was not a job meant for dumb blondes. We worked hard. We also enjoyed a lot of fringe benefits. We shopped at the best places and enjoyed five-star accommodation. We could pick a place on the map and vacation there, thanks to the free tickets allotted to us,” she says. Eisa was appointed chief purser of the ill-fated Mumbai-Karachi-Frankfurt Pan Am flight. But that day, she reported sick and thus the task of heading the 12-member flight crew fell to Neerja. On September 5, 1986, Harish Bhanot was at a press conference when he heard about the hijacking. He rushed to the office of his friend who worked in Hindustan Lever, which tried to get more information. Throughout the day, like other families of crew members and passengers, he kept calling the Pan Am office for updates. But the moment her mother, Rama, heard about the incident, she broke down: “Neerja isn’t returning home.” Kirloskar, who was visiting her brother in the US and was supposed to take the return flight from Frankfurt and travel together with Neerja, was glued to the television even though news coverage was very limited then. Most of Neerja’s friends, including Lewis, came to know of the tragedy a couple of days later when it appeared in the newspapers. The death of the 22-year-old left the family devastated. While life inched to normalcy for others, Rama could not come to terms with Neerja’s death and slipped into depression. “After all of us left for our work, she was was left alone at home with Neerja’s things,” he says. While Harish passed away in 2008, Rama died in December 2015, two days before the trailor for Neerja was released. For many years, she believed that she could communicate with her deceased daughter and wrote down “messages” from Neerja. Akhil believed her. Aneesh, however, dismisses this as her illusion. Had the hijackers not cut Neerja’s life short, she would have returned to Mumbai on her 23rd birthday, which she wished to be a family affair. Instead, her family collected her coffin from the airport. Her father wrote: “She was cremated on September 8 at 11 am amidst chanting of her favourite mantras, as we said ‘Goodbye darling, please keep coming’.”