Archaeology and Monuments: India

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

[[File: Pir Ghalib in north Delhi.jpg|Pir Ghalib in north Delhi; [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Why-monetising-heritage-may-be-the-key-to-16082017005005 Manimugdha Sharma, Why monetising heritage may be the key to keeping it safe, August 16, 2017: The Times of India]|frame|500px]] | [[File: Pir Ghalib in north Delhi.jpg|Pir Ghalib in north Delhi; [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Why-monetising-heritage-may-be-the-key-to-16082017005005 Manimugdha Sharma, Why monetising heritage may be the key to keeping it safe, August 16, 2017: The Times of India]|frame|500px]] | ||

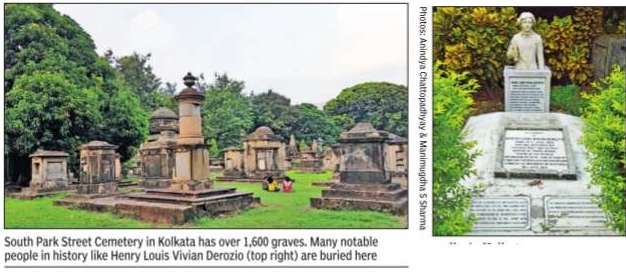

| − | [[File: South Park Street Cemetery, Kolkata.jpg|A statue and South Park Street Cemetery, Kolkata; [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Why-monetising-heritage-may-be-the-key-to-16082017005005 Manimugdha Sharma, Why monetising heritage may be the key to keeping it safe, August 16, 2017: The Times of India]|frame|500px]] | + | [[File: A statue and South Park Street Cemetery, Kolkata.jpg|A statue and South Park Street Cemetery, Kolkata; [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=Why-monetising-heritage-may-be-the-key-to-16082017005005 Manimugdha Sharma, Why monetising heritage may be the key to keeping it safe, August 16, 2017: The Times of India]|frame|500px]] |

Revision as of 20:09, 16 August 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

1949- 2010

As the govt wants to amend heritage laws, experts think aloud about ways to protect buildings and beat the perception that history impedes development

A couple of weeks after the great Russian artist Nicholas Roerich passed away in Himachal Pradesh, an exhibition of his works was held in Delhi. It was late December 1947 and India was independent. Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru came for the inauguration.

“I hope that when we are a little freer from the cares of the moment, we shall pay very special attention to the ancient cultural monuments of the country, not only just to protect them from decay but somehow to bring them more in line with our education, with our lives, so that we may imbibe something of the inspiration that they have, Pandit Nehru said while inaugurating the exhibition. A profound expression of intent, one would think. At that point in 1947, there were 2,826 protected monuments in India. Yet govern mental apathy towards them was of monumental proportions. Nehru was reminded of this by many events and people. Leela Shiveshwarkar, an author and a leading design er of that time, had written an article in The Times of India in 1949 in which she had called this negligence “inexcusable“. And no, she wasn't willing to buy the PM's argument that there were more pressing concerns.

“The government must take immediate steps to do all that is possible for these monuments. Let it not be said that there are other more pressing problems. There can be no other problem in relation to time more pressing than this. These are the only things which India can look back to as her rightful heritage, and if these are lost through sheer neglect, what else is left?“ Shiveshwarkar said in her piece.

Two years later, Parliament passed the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Declaration of National Importance) Act, 1951, and added 450 other monuments to the previous list.

Nehru had kept his word.

But the inadequacy of the leg islation was discovered soon, as Parliament had to sanction every new inclusion in the list. An amendment Bill was proposed. While debating it in 1953, Congress MP from Madras, K Rama Rao, liked the Bill for its “judicious mixture of tombs and tem ples“, but won dered how the archaeolo g y department was helping Nehru in his “discovery of India every day“.

The 1951 law was repealed and a new one enacted as The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, followed by a set of rules in 1959. This was the most comprehensive legislation for the protection of heritage.

Then in 2010, the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) Act came about as an amendment to the principal Act. Among many things, this amendment introduced the concept of prohibited and regulated zones. And it's this concept that the Modi government wants to amend to allow “public works“ in the prohibited zone of 100 metres of a protected monument.

The prohibition clause has been a contentious issue since the 2010 amendment, with many arguing that heritage buildings act as obstacles to development. A general impression was thus wrongly created that heritage and modernity are contradictory . That this clause is now up for amendment shows that this gulf is deemed unbridgeable.

“Heritage and modernity can coexist to enrich the character of urban space. The adaptive reuse of historical structures could be financially sustainable too,“ said Tathagata Neogi, a British-trained archaeologist who now conducts heritage walks in Kolkata.

To illustrate his point, he gave the example of South Park Street Cemetery in Kolkata. “It is suffering from an acute lack of funds. Although they have recently started a ticketing system, more can be done to generate revenue. This cemetery , containing more than 1,600 graves of eclectic architecture, could be converted into an open-air, nuanced museum of colonialism using cutting-edge technology like augmented reality ,“ Neogi said.

He continued, “Many old buildings in north Kolkata are crumbling due to lack of maintenance.Some of these families do not want to give up their ancestral homes, but lack the training and resources to maintain them. What if we can train them and show them how to make their properties profitable?“ Neogi also said that old structures could be turned into “offices, shopping centres or themed restaurants without pulling them down and building characterless new concrete, steel and glass structures“.

Delhi, for all its abundance of heritage, strangely , has very few heritage hotels, resorts and homestays. That raises the fundamental question: can heritage be monetised in Delhi? “A very good question. I really think this needs to be pursued urgently in Delhi,“ said Swapna Liddle, convenor of Intach Delhi Chapter. “A good starting point has to be for all stakeholders to have a dialogue. It is important for owners of heritage buildings to not only be aware of their responsibilities and the development restrictions their properties are subject to, but to be informed of the incentives and benefits that the state can give them. The latter must of course be first spelt out and formulated--tax exemptions, loans for conservation, technical advice, and the ability to change the use to commercial purposes, subject to the use not being such as will damage the heritage character of the building.“

Neogi also stressed on the need to have a “more accommodating urban development policy that goes beyond the simple binary of heritage vs development“.

This should be Delhi's, nay India's pressing concern.

For Rock Carvings found in Delhi's JNU, see Delhi: J