Gulbarga

| (One intermediate revision by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

[http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-opinion/a-mosque-with-a-persian-touch/article24243758.ece Rana Safvi, The Jami Masjid in Gulbarga also brings to mind the Great Mosque of Cordoba, June 24, 2018: ''The Hindu''] | [http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-opinion/a-mosque-with-a-persian-touch/article24243758.ece Rana Safvi, The Jami Masjid in Gulbarga also brings to mind the Great Mosque of Cordoba, June 24, 2018: ''The Hindu''] | ||

| − | [[File: Jami Masjid, Gulbarga, Karantaka.jpg|Jami Masjid, Gulbarga <br/> From: [http://tourism.gov.in/karnataka | + | [[File: Jami Masjid, Gulbarga, Karantaka.jpg|Jami Masjid, Gulbarga <br/> From: [http://tourism.gov.in/karnataka ''Ministry of Torism, Government of Karnataka'']|frame|500px]] |

| + | |||

Mohammad bin Tughlaq, who ruled from 1321 to 1351 as the Delhi Sultan, captured large parts of the Deccan including Gulbarga. In 1347, a Tughlaq officer named Alauddin Hasan revolted against Tughlaq and declared his independence by establishing the Bahmani kingdom (1347-1527) with Gulbarga as its capital. Hasan built Gulbarga as a fortress city. The Bahmani Sultans ruled from here till the capital of the kingdom was shifted to Bidar in 1424. | Mohammad bin Tughlaq, who ruled from 1321 to 1351 as the Delhi Sultan, captured large parts of the Deccan including Gulbarga. In 1347, a Tughlaq officer named Alauddin Hasan revolted against Tughlaq and declared his independence by establishing the Bahmani kingdom (1347-1527) with Gulbarga as its capital. Hasan built Gulbarga as a fortress city. The Bahmani Sultans ruled from here till the capital of the kingdom was shifted to Bidar in 1424. | ||

Latest revision as of 09:36, 24 June 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

[edit] Jami Masjid

[edit] Architecture

From: Ministry of Torism, Government of Karnataka

Mohammad bin Tughlaq, who ruled from 1321 to 1351 as the Delhi Sultan, captured large parts of the Deccan including Gulbarga. In 1347, a Tughlaq officer named Alauddin Hasan revolted against Tughlaq and declared his independence by establishing the Bahmani kingdom (1347-1527) with Gulbarga as its capital. Hasan built Gulbarga as a fortress city. The Bahmani Sultans ruled from here till the capital of the kingdom was shifted to Bidar in 1424.

When Mohammad bin Tughlaq shifted his capital to Daulatabad in the Deccan, he took artisans and architects with him. However, the Bahmani Sultans chose to look towards Persia as a source of inspiration, much like Europe looked towards Greek architecture, impressed with its soaring arches and a lightness of touch. Sometimes this was combined with existing and developing local styles and at other times the architecture of the Tughlaq style remained, as seen in the tombs of the Bahmani kings in Gulbarga.

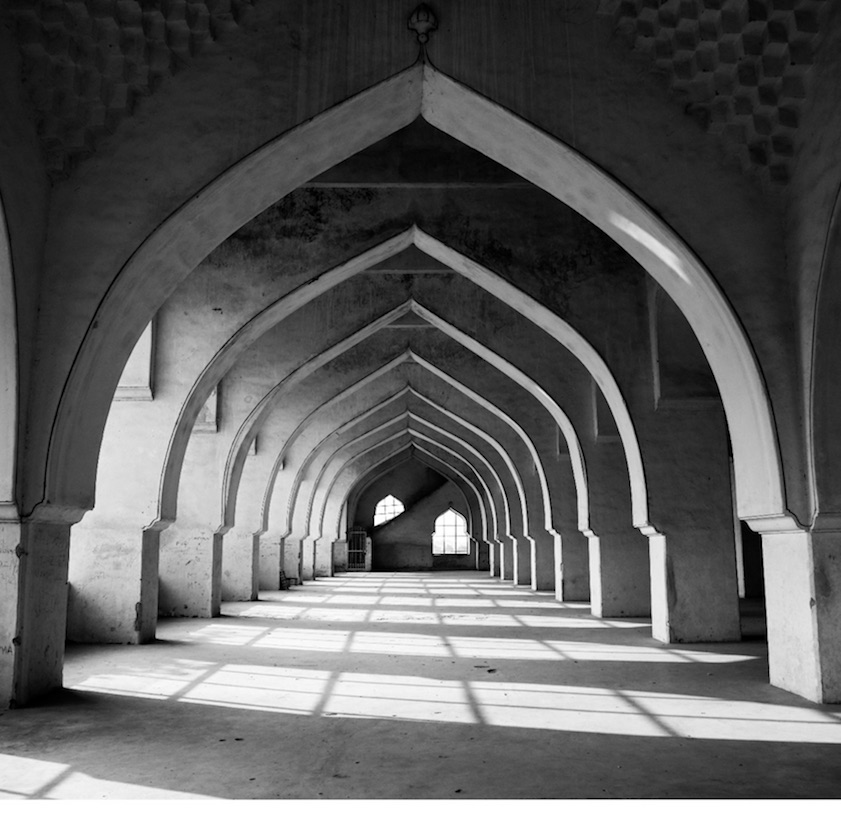

Inside the mosque

Approaching Gulbarga, I could see the irregular fortress walls stretching into the distance for nearly 3 km. They are 50 ft-thick double walls and are surrounded by a moat carved out of living rock. The moat is 30 yards wide in places. I could see some solid semicircular bastions as we entered through one of the two entrance gateways. I was a little disappointed when I saw the crumbling wall and gateway, with cattle happily grazing there. But the first sight of the grand Jami Masjid, or congregational mosque, built inside was enough to set my heart soaring.

The Jami Masjid was completed in 1367. Even now, it stands as a firm testimony to the glory of a bygone kingdom. Though I have not visited Cordoba in Spain yet, as soon as I entered the Jami Masjid I could imagine why there are comparisons with the Great Cathedral-Mosque of Cordoba.

The uniqueness of the mosque is that it has no open courtyard and the entire structure is covered by a roof. According to art historian Percy Brown, “Some of the originality of its design and construction may be due to the [fact] that it was produced under the direction of a hereditary architect named Rafi, not of India, but from the distant town of Kazvin in northern Persia. It is possible that this talented descendant of a noted family of architects evolved the scheme of this mosque from his inner consciousness, that its unusual conformation was the result of his own genius.”

He also says: “He may have looked to the occident for his inspiration, and that at the back of his mind was some idea of a domed and vaulted hall of the basilica type, an occasional form of Moslem religious edifice in some of the countries of eastern Europe.”

The mosque is divided into wide arched sections with a spacious area on the west with the Mihrab. This space is covered by a high central dome. Rows of aisles with 68 bays, each shaped like a cupola, give the pillared hall a magnificent appearance. There are honeycomb pendentives on the four sides of each cupola.

These rows of wide-spanned single arches with low imposts gave me goosebumps with their perfection and geometrical symmetry. After I prayed in front of the western Mihrab, I couldn’t resist getting myself photographed under every arched bay.

Plain from the outside

The mosque looks solid and plain from outside, much in contrast to the the one-aisled mosques of Delhi with their open courtyards and decorated entrances that I was accustomed to. Even the lofty arch on the northern entrance was simple without any calligraphy.

As the area in front of the mosque was crowded, I got a better view from a nearby bastion on top of which lies one of the biggest cannons in the world. From this elevation I could see the central dome, the four smaller side domes, and the arched openings running on three sides of the mosque.

This mosque influenced many other mosques of the Deccan built subsequently. Brown says: “The clerestory supporting the dome became a feature of the building art in these parts, while the wide span and low imposts of the cloister arches figured as the keynote to many of the later monuments.” These included the Kali and Khirkee mosques in Delhi.