M. Karunanidhi

(→Vignettes) |

(→A brief biography) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

''M Karunanidhi- A brief biography, 1972-2018'' | ''M Karunanidhi- A brief biography, 1972-2018'' | ||

| + | ==Political legacy== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F09&entity=Ar01800&sk=B9D12E7D&mode=text Sanjiv Shankaran, He Helped Fashion Today’s India, August 9, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Karunanidhi’s political journey had a positive influence on his state and country'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The sight of politicians of all stripes paying homage to M Karunanidhi, draped in the tricolour, and describing him as a great son of India encapsulated the essence of his journey from a young radical to a consummate mainstream politician. Starting off in a movement which initially had an ambivalent relationship with Indian nationalism, he played an important political role in strengthening it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The context of his political journey started with the formation of South Indian Welfare Association in 1917 to combat the disproportionate presence of Brahmins in the colonial administration. Positioning itself against the dominant Congress, by 1949 it birthed the DMK which championed the causes of social justice and Tamil nationalism. Karunanidhi’s childhood, marked by impoverishment and humiliation stemming from an oppressive caste system, drew him into the Dravidian movement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A trait which helped him and his party was his gift in using Tamil. For a movement that used cinema to propagate its ideology, his talent as a writer was invaluable. Long after he won the first of his 13 consecutive assembly elections in 1957, conversations about him would inevitably touch upon his skilled use of Tamil to communicate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To gauge Karunanidhi’s impact on both Tamil Nadu and national politics, it’s necessary to unpack three intertwined aspects: social reform, administration and politics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Dravidian movement was a mass movement which reflected the needs and aspirations of common people. As a fivetime chief minister, Karunanidhi used a combination of reservations and reallocation of government resources towards welfare measures to meet it. Following the DMK’s first government in 1967 under the leadership of CN Annadurai, there has been little space in the state for any other political ideology. For over five decades, DMK and its offshoot, AIADMK, have administered the state. Neither party moved away from this basic approach even though the circumstances in which social justice can be situated have changed over time. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The approach to put welfare schemes for carefully chosen sections of society at the heart of public spending, which Karunanidhi was adept at, is now the basic template across India regardless of the political party in power. Who isn’t populist? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Twice did Karunanidhi governments get dismissed by the capricious use of Article 356. Given his grounding in Tamil nationalism and a dominant Centre in the early stages, he was a strong advocate of a brand of federalism which allowed states more space. Over time and with judicial interventions, India’s federalism has become a lot more state-centric. Consequently, there’s space for sub-nationalism along with a simultaneous identification with India. Creating this space has strengthened India, contrary to initial fears. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Karunanidhi enjoyed a unique place in Tamil Nadu. While his main rivals MG Ramachandran and J Jayalalithaa too enjoyed popular support, they rarely received endorsement of the intelligentsia in the manner that Karunanidhi did. It put him in an ideal place to go beyond his role as a political leader when dealing with social problems. If fighting inequities of caste was the primary motive of the Dravidian movement, Karunanidhi could have done more. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Caste continues to blight everyday life in the state. Dalits have at times been subjected to nothing less than hate crimes. But a stalwart of the Dravidian movement, who was part of its early struggles, was muted in his response. The only explanation seems to be that early idealism gave way to a politician’s acute awareness of electoral arithmetic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the political side, DMK followed the general trend in India. The family was first among equals. Anecdotal evidence of the insidious overlap between business and political interests mounted. If political parties are forced to distribute cash ahead of the elections, politicians who dominated the state are also to blame for converting the voter into a cynic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Perhaps, the underrated dimension to the policies of Karunanidhi and his political rivals is the combined impact they have had on economy and society. A look at Tamil Nadu’s trajectory shows that it has probably made the most notable improvement among states in the last three decades. So much so that when in 2013 a committee headed by Raghuram Rajan ranked states on development using a combination of economic and social parameters, Tamil Nadu came third, ahead of its economic peers Gujarat and Maharashtra. This ranking is telling because just two decades before it, the state’s poverty levels exceeded the national average. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the underwhelming performance in dealing with society’s fault lines and the high prevalence of dayto-day corruption, Dravidian politics produced results in areas that mattered and Karunanidhi, its longest serving chief minister, deserves credit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Karunanidhi spent over seven decades in politics and around two decades as chief minister. When he was first elected in 1957 secessionism was still on DMK’s agenda. By the time he won his last assembly election in 2016, Tamil Nadu had successfully seen through its most dangerous phase and Karunanidhi had emerged as an important player in national politics. Even as the state’s political culture worsened, economic conditions improved and it remained relatively free of communal problems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A part of the credit should go to Karunanidhi, who strove to find a balance between realpolitik and his roots in a movement bent on social emancipation. He influenced politics not just in his state but also at the national level. On balance, it was a positive influence. | ||

==1969: ascension== | ==1969: ascension== | ||

| Line 91: | Line 123: | ||

[https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F08&entity=Ar02202&sk=6E811F19&mode=text Arun Ram, As politician turned patriarch, family became centre of party, August 8, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F08&entity=Ar02202&sk=6E811F19&mode=text Arun Ram, As politician turned patriarch, family became centre of party, August 8, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | [[File: M. Karunanidhi with younger son Stalin and wife Dayalu Ammal.jpg|M. Karunanidhi with younger son Stalin and wife Dayalu Ammal <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F08&entity=Ar02202&sk=6E811F19&mode=text Arun Ram, As politician turned patriarch, family became centre of party, August 8, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

On a September day in 1944, while a 20-year-old bridegroom was waiting for his bride, an anti-Hindi rally passed. “Long live Tamil, down with Hindi,” shouted M Karunanidhi, the groom, and joined the protestors. The bride, Padmavathi, had to wait more than an hour before some relatives brought Karunanidhi back. | On a September day in 1944, while a 20-year-old bridegroom was waiting for his bride, an anti-Hindi rally passed. “Long live Tamil, down with Hindi,” shouted M Karunanidhi, the groom, and joined the protestors. The bride, Padmavathi, had to wait more than an hour before some relatives brought Karunanidhi back. | ||

| Line 107: | Line 140: | ||

In November 2010, DMK ideologue the late Chinna Kuthoosi told TOI that Karunanidhi knew that promoting too many family members would be bad for the party, but he probably had his compulsions. “As long as Karunanidhi is alive,” he had said, “there will be no problem.” And now, the question is: Will problems begin? | In November 2010, DMK ideologue the late Chinna Kuthoosi told TOI that Karunanidhi knew that promoting too many family members would be bad for the party, but he probably had his compulsions. “As long as Karunanidhi is alive,” he had said, “there will be no problem.” And now, the question is: Will problems begin? | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Literature, cinema= | ||

| + | ==Oratory, eloquence== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F08&entity=Ar02200&sk=F41D6A75&mode=text Kamini Mathai, Film or politics, this scriptwriter had best lines, August 8, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: M. Karunanidhi with actor Jackie Chan in Chennai in 2008.jpg|M. Karunanidhi with actor Jackie Chan in Chennai in 2008 <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F08%2F08&entity=Ar02200&sk=F41D6A75&mode=text Kamini Mathai, Film or politics, this scriptwriter had best lines, August 8, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sharp dialogue, veiled metaphor, innuendo, rhyme and rhetoric — Karunanidhi employed every literary tool with aplomb through his decades as a scriptwriter and later as a politician known for fiery speeches. A master of the Tamil language, he championed the cause of regional pride, and inspired politicians in other southern states to speak up for their languages against the imposition of Hindi. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Karunanidhi’s love for the language began as a child when he joined local theatre troupes, and wrote and acted in plays. Tamil pride took root in the state in the 1930s, and Karunanidhi learned at the knee, so to speak, of former chief minister and DMK founder CN Annadurai, whose command of the language won him a mass following. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a poet and a lyricist, Karunanidhi was able to take the lessons of his mentor further to win hearts and minds. His eulogy to Annadurai in 1969 was made into gramophone records and played across the state. In a career spanning seven decades, he scripted 77 films, and earned a name as one who could successfully push ideology into a commercial film. Kalaignar — or scholar of the arts as he was known — wove the Dravidian ideology of social transformation and anti-Brahminism into plots and lines. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dravidian writer historian ‘Sangoli’ K Thirunavukkarasu describes Karunanidhi’s ability to cloak political ideology in dialogue as nonpareil. “His scripts had coded messages to his potential votebank,” he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While actors came and went, Karunanidhi continued to light up the screen and political scene, using the era’s superstars — MGR and Sivaji Ganesan — as the medium for his message. At age 92, he wrote dialogue for a TV serial on Hindu saint Ramanujar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “His oratory and use of Tamil mesmerised even his detractors,” says author R Kannan. “He emulated Anna but was more feisty.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though critics say he at times eased back on Dravidian tenets, he always championed the Tamil language and was one of its strongest proponents.He replaced the traditional invocation song at state functions with a paean to the ‘Tamil Mother’. His government introduced Tamil pujas in temples, he created a separate ministry for Tamil, and revived the World Tamil Conferences. | ||

=A significant role in coalition governments, 1977-2016= | =A significant role in coalition governments, 1977-2016= | ||

Latest revision as of 10:48, 9 September 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] The man

[edit] A brief biography

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

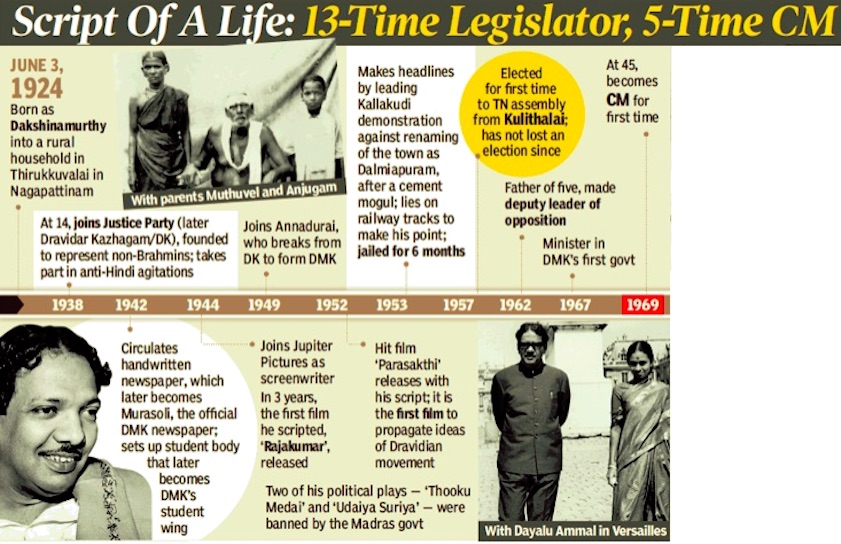

See graphic:

M Karunanidhi- A brief biography, 1938-1969

M Karunanidhi- A brief biography, 1972-2018

[edit] Political legacy

Sanjiv Shankaran, He Helped Fashion Today’s India, August 9, 2018: The Times of India

Karunanidhi’s political journey had a positive influence on his state and country

The sight of politicians of all stripes paying homage to M Karunanidhi, draped in the tricolour, and describing him as a great son of India encapsulated the essence of his journey from a young radical to a consummate mainstream politician. Starting off in a movement which initially had an ambivalent relationship with Indian nationalism, he played an important political role in strengthening it.

The context of his political journey started with the formation of South Indian Welfare Association in 1917 to combat the disproportionate presence of Brahmins in the colonial administration. Positioning itself against the dominant Congress, by 1949 it birthed the DMK which championed the causes of social justice and Tamil nationalism. Karunanidhi’s childhood, marked by impoverishment and humiliation stemming from an oppressive caste system, drew him into the Dravidian movement.

A trait which helped him and his party was his gift in using Tamil. For a movement that used cinema to propagate its ideology, his talent as a writer was invaluable. Long after he won the first of his 13 consecutive assembly elections in 1957, conversations about him would inevitably touch upon his skilled use of Tamil to communicate.

To gauge Karunanidhi’s impact on both Tamil Nadu and national politics, it’s necessary to unpack three intertwined aspects: social reform, administration and politics.

The Dravidian movement was a mass movement which reflected the needs and aspirations of common people. As a fivetime chief minister, Karunanidhi used a combination of reservations and reallocation of government resources towards welfare measures to meet it. Following the DMK’s first government in 1967 under the leadership of CN Annadurai, there has been little space in the state for any other political ideology. For over five decades, DMK and its offshoot, AIADMK, have administered the state. Neither party moved away from this basic approach even though the circumstances in which social justice can be situated have changed over time.

The approach to put welfare schemes for carefully chosen sections of society at the heart of public spending, which Karunanidhi was adept at, is now the basic template across India regardless of the political party in power. Who isn’t populist?

Twice did Karunanidhi governments get dismissed by the capricious use of Article 356. Given his grounding in Tamil nationalism and a dominant Centre in the early stages, he was a strong advocate of a brand of federalism which allowed states more space. Over time and with judicial interventions, India’s federalism has become a lot more state-centric. Consequently, there’s space for sub-nationalism along with a simultaneous identification with India. Creating this space has strengthened India, contrary to initial fears.

Karunanidhi enjoyed a unique place in Tamil Nadu. While his main rivals MG Ramachandran and J Jayalalithaa too enjoyed popular support, they rarely received endorsement of the intelligentsia in the manner that Karunanidhi did. It put him in an ideal place to go beyond his role as a political leader when dealing with social problems. If fighting inequities of caste was the primary motive of the Dravidian movement, Karunanidhi could have done more.

Caste continues to blight everyday life in the state. Dalits have at times been subjected to nothing less than hate crimes. But a stalwart of the Dravidian movement, who was part of its early struggles, was muted in his response. The only explanation seems to be that early idealism gave way to a politician’s acute awareness of electoral arithmetic.

On the political side, DMK followed the general trend in India. The family was first among equals. Anecdotal evidence of the insidious overlap between business and political interests mounted. If political parties are forced to distribute cash ahead of the elections, politicians who dominated the state are also to blame for converting the voter into a cynic.

Perhaps, the underrated dimension to the policies of Karunanidhi and his political rivals is the combined impact they have had on economy and society. A look at Tamil Nadu’s trajectory shows that it has probably made the most notable improvement among states in the last three decades. So much so that when in 2013 a committee headed by Raghuram Rajan ranked states on development using a combination of economic and social parameters, Tamil Nadu came third, ahead of its economic peers Gujarat and Maharashtra. This ranking is telling because just two decades before it, the state’s poverty levels exceeded the national average.

Despite the underwhelming performance in dealing with society’s fault lines and the high prevalence of dayto-day corruption, Dravidian politics produced results in areas that mattered and Karunanidhi, its longest serving chief minister, deserves credit.

Karunanidhi spent over seven decades in politics and around two decades as chief minister. When he was first elected in 1957 secessionism was still on DMK’s agenda. By the time he won his last assembly election in 2016, Tamil Nadu had successfully seen through its most dangerous phase and Karunanidhi had emerged as an important player in national politics. Even as the state’s political culture worsened, economic conditions improved and it remained relatively free of communal problems.

A part of the credit should go to Karunanidhi, who strove to find a balance between realpolitik and his roots in a movement bent on social emancipation. He influenced politics not just in his state but also at the national level. On balance, it was a positive influence.

[edit] 1969: ascension

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

India in 1969, the year of M Karunanidhi’s ascension

[edit] Vignettes

August 8, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

EARLY START

In his autobiography, ‘Nenjukku Neethi’ (justice for the heart), Karunanidhi recalls being inspired to take to politics after reading a lesson on Justice Party leader Panagal Raja. He was 14 when he joined the Justice Party.

PLAYING TO WIN

In his teens, he set up a students’ group to propagate the Dravidian movement. A rival group emerged and Karunanidhi was worried about the threat they posed. When the rivals scheduled a play and the lead actor went missing, Karunanidhi offered to step in — only if the rival group merged with his. It agreed. It was just the kind of negotiation he would employ all his life.

ALWAYS THE SUN

When Kalaignar started meditation classes in his 80s, he chose the sun as his focus, said his yoga trainer, Sridharan, who taught him with with TKV Desikachar, founder of Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram. Seemed appropriate for a man who’d led a party with the ‘Rising Sun’ as its election symbol for decades.

WRITE ROUTINE

He’d rise at 5am to read and write for the DMK newspaper with a cup of coffee. Subbulakshmi Jagadeesan, one of TN’s first women mantris, recalls a call at 5am: “He wanted to know if I’d read a piece on infanticide. I had to confess I hadn’t woken up.”

[edit] Karunanidhi’s politics

[edit] Regional Pride

Jayaraj Sivan, He Made Regional Pride His Political Capital, August 8, 2018: The Times of India

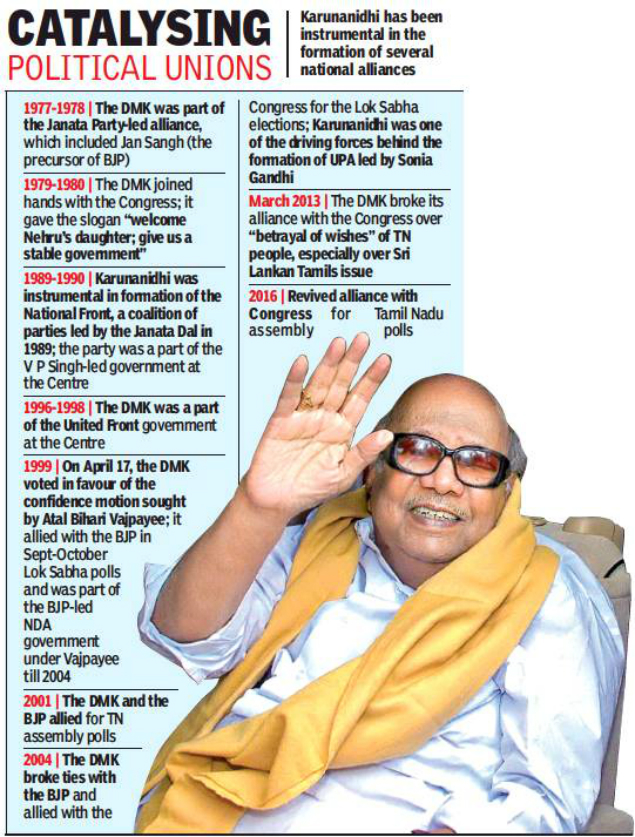

80-YEAR LEGACY: M Karunanidhi’s ability to weave Tamil identity, anti-caste ideals & family interests has influenced politics of parties across the country

For a man who rarely made his way to Delhi, his presence was always felt in political circles in the national capital. M Karunanidhi had the ability to sense the popular mood and cobble together alliances that often won both at the Centre and the state.

The wily satrap could ally with the Congress after suffering its Emergency-era excesses. He could sign up with the BJP, a party that seemed to stand for everything the Dravidian movement opposed. He’s been part of the United Front, the BJP-led NDA and the UPA, often wielding power disproportionate to his strength in Parliament. Through it all, he retained a base built on the Dravidian ideals of social reform and welfare, empowerment of backward classes and promoting Tamil identity despite allegations of corruption that never quite went away.

His ability to play regionalism as a card yet negotiate with national parties as an equal served as a template for other parties across the country. In UPA-1, Karunanidhi with his strength of 16 MPs brokered seven ministerial posts and a Rajya Sabha seat for daughter Kanimozhi. In UPA-2, despite a weakened position, he got five ministerial berths on the back of 18 Lok Sabha seats. Even as a DMK minister in the UPA government was seen as the prime suspect in the 2G spectrum scam, the party quit the Centre in 2013 over India’s failure to take a strong stand against Sri Lanka’s handling of the civil war.

Alliances made and unmade in the 1970s illustrate how opportunistic he was: When an embattled Indira Gandhi found the Congress fracturing on her watch in 1969, Karunanidhi was quick to offer his 25 MPs. She then tied up with him when he called polls a year early. The Congress(I)-DMK combine won the 1971 state poll. Within a few years, they were on opposite sides when Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency in 1975. DMK opposed it and many national leaders found a safe haven in TN. A vengeful Indira Gandhi dismissed the DMK government after the Sarkaria Commission accused him of corruption. But less than two years later, sensing an opportunity to oust AIADMK’s MG Ramachandran, he allied with her again. These alliances were also a means to weaken Congress in the state. Wanting to ensure numbers in Lok Sabha, Indira Gandhi agreed not to contest a single state seat and gave in to all his conditions. With that, he effectively kept Congress out of power in the state for half a century.

Despite new parties like MDMK, PMK, DMDK and VCK emerging in TN — many with the intention of countering DMK — Karunanidhi managed to draw them into his fold. He was adept at weakening opponents through electoral tie-ups, promising them much yet denying a share in power. He managed to cultivate a pro-DMK faction in every party, except AIADMK.

Battling AIADMK proved harder than playing Delhi politics. He had to spend 12 years in the opposition until elections were held after MGR's death. The comeback in 1996 was a watershed moment. DMK won in alliance with a Congress faction, led by GK Moopanar and P Chidambaram, and a ringing endorsement from superstar Rajinikanth. Within three years, he dumped TMC to ally with BJP as part of NDA in 1999. Again, DMK MPs, including Murasoli Maran, became ministers with plum portfolios. This was also a period when DMK’s ties with Congress reached its lowest, especially after the Jain Commission that probed Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination suggested that DMK abetted the crime with its support for LTTE. Six years later, however, he’d made peace and in 2004, firmed up an alliance with Sonia Gandhi’s Congress. It’s an alliance that endures.

It remains to be seen if Stalin has imbibed the trade secret — to forge alliances that would propel DMK back into national politics.

[edit] Vis-à-vis Dr. J. Jayalalithaa

The only point of business Karuna, Jaya agreed upon, August 8, 2018: The Times of India

MKarunanidhi and J Jayalalithaa as fierce political rivals could never accept the other’s decisions — except when it came to industrialisation, and this rare consensus brought fortune to Tamil Nadu, making it the second richest state.

When the economy was opened up in the 1990s, TN benefited from a wave of investments, starting with the entry of Ford India during AIADMK’s tenure. Hyundai, Saint Gobain, Nokia, Huawei, Renault, Daimler and others followed over the decades, doing business in a conducive environment no matter which government was in power. “Karunanidhi was always receptive to suggestions and inputs. He was sensitive to the needs of industry,” said N Srinivasan, vice-chairman and MD of The India Cements. Srinivasan first met Karunanidhi in 1968 when the latter was public works minister. “When it came to business, he always looked ahead,” said Srinivasan.

The DMK government’s focus on industry resulted in TN gaining manufacturing capabilities across sectors. In the run-up to the year 2000, when IT companies were busy setting up base in Bengaluru and Hyderabad, it dawned on Karunanidhi that 80% of the workforce in those two cities and that sector were migrants from TN. In less than a year, his government not only drew up a roadmap for the IT sector but also promoted a massive IT office space project, Tidel Park.

While bankers considered it merely a real estate project, the state stood guarantee for the lenders. Chennai joined the country’s elite IT club and there was no looking back. Chennai’s Old Mahabalipuram Road was designated the ‘IT Corridor’ and a six-laning plan led to the development of the stretch for office, industrial and residential projects. The DMK government also set aside 1,000 acres at the other end of IT corridor for companies to develop their own IT parks.

[edit] Family

From: Arun Ram, As politician turned patriarch, family became centre of party, August 8, 2018: The Times of India

On a September day in 1944, while a 20-year-old bridegroom was waiting for his bride, an anti-Hindi rally passed. “Long live Tamil, down with Hindi,” shouted M Karunanidhi, the groom, and joined the protestors. The bride, Padmavathi, had to wait more than an hour before some relatives brought Karunanidhi back.

For young Karunanidhi, who took the plunge into the Dravidian movement as a teenager, the movement and the party were his family. Two more marriages and six children later, he grew into a patriarch, and detractors said his family became the party.

By 2009, family members occupied important posts in the party and the UPA government at the Centre. MK Stalin remained CM-in-waiting, while older son MK Alagiri was Union minister for chemicals and fertilisers, and daughter Kanimozhi was a Rajya Sabha member. Grandnephew Dayanidhi Maran was Union IT and telecom minister.

Political dynasties have ruled the roost in Indian politics, from the Nehru-Gandhi family at the Centre, the Abdullahs in Kashmir, the Badals in Punjab to the Karunakaran family in Kerala. But none probably matched the Karunanidhi tribe in size and influence.

Stalin is the only one in the family who is seen to have earned his stripes, having served time during the Emergency and working his way up the ranks. CM Karunanidhi kept Stalin out of his cabinet in 1989 and 1996 though the son was an MLA. But, there was no threat to the younger son’s eventual ascension as Vaiko, DMK’s rising star, was forced out in 1993. The only other rebellion came from within the family, but Alagiri proved to be just sound and fury. In fact, in the nearly 50 years that he was at the helm of the party after Annadurai’s death, there has never been a challenge to his leadership.

Karunanidhi shared a special relationship with his nephew Murasoli Maran, and made Maran’s younger son Dayanidhi a central minister in 2004 and 2009. Dayanidhi remains in legal tangles including the ‘telephone exchange case’ and the ‘Aircel-Maxis case’ and the families have fallen out publicly, but it was the Marans’ closeness to Karunanidhi that built the Sun Group into the behemoth it is today.

Against the backdrop of the 2G spectrum case and Radia tapes that featured the names of Stalin, Kanimozhi, Alagiri and Karunanidhi’s wives Dayalu Ammal and Rajathi Ammal, the late political commentator Cho Ramaswamy told TOI in November 2010 that he was convinced that Karunanidhi was one of the most loving fathers he knew. “His biggest mistake was introducing so many of his family members in politics,” he had said. “He became a puppet, and there were too many puppeteers.” Karunanidhi took criticism of nepotism in his stride, but felt the pain when Kanimozhi went to jail and investigators wanted to question an ailing Dayalu Ammal.

In November 2010, DMK ideologue the late Chinna Kuthoosi told TOI that Karunanidhi knew that promoting too many family members would be bad for the party, but he probably had his compulsions. “As long as Karunanidhi is alive,” he had said, “there will be no problem.” And now, the question is: Will problems begin?

[edit] Literature, cinema

[edit] Oratory, eloquence

From: Kamini Mathai, Film or politics, this scriptwriter had best lines, August 8, 2018: The Times of India

Sharp dialogue, veiled metaphor, innuendo, rhyme and rhetoric — Karunanidhi employed every literary tool with aplomb through his decades as a scriptwriter and later as a politician known for fiery speeches. A master of the Tamil language, he championed the cause of regional pride, and inspired politicians in other southern states to speak up for their languages against the imposition of Hindi.

Karunanidhi’s love for the language began as a child when he joined local theatre troupes, and wrote and acted in plays. Tamil pride took root in the state in the 1930s, and Karunanidhi learned at the knee, so to speak, of former chief minister and DMK founder CN Annadurai, whose command of the language won him a mass following.

As a poet and a lyricist, Karunanidhi was able to take the lessons of his mentor further to win hearts and minds. His eulogy to Annadurai in 1969 was made into gramophone records and played across the state. In a career spanning seven decades, he scripted 77 films, and earned a name as one who could successfully push ideology into a commercial film. Kalaignar — or scholar of the arts as he was known — wove the Dravidian ideology of social transformation and anti-Brahminism into plots and lines.

Dravidian writer historian ‘Sangoli’ K Thirunavukkarasu describes Karunanidhi’s ability to cloak political ideology in dialogue as nonpareil. “His scripts had coded messages to his potential votebank,” he says.

While actors came and went, Karunanidhi continued to light up the screen and political scene, using the era’s superstars — MGR and Sivaji Ganesan — as the medium for his message. At age 92, he wrote dialogue for a TV serial on Hindu saint Ramanujar.

“His oratory and use of Tamil mesmerised even his detractors,” says author R Kannan. “He emulated Anna but was more feisty.”

Though critics say he at times eased back on Dravidian tenets, he always championed the Tamil language and was one of its strongest proponents.He replaced the traditional invocation song at state functions with a paean to the ‘Tamil Mother’. His government introduced Tamil pujas in temples, he created a separate ministry for Tamil, and revived the World Tamil Conferences.

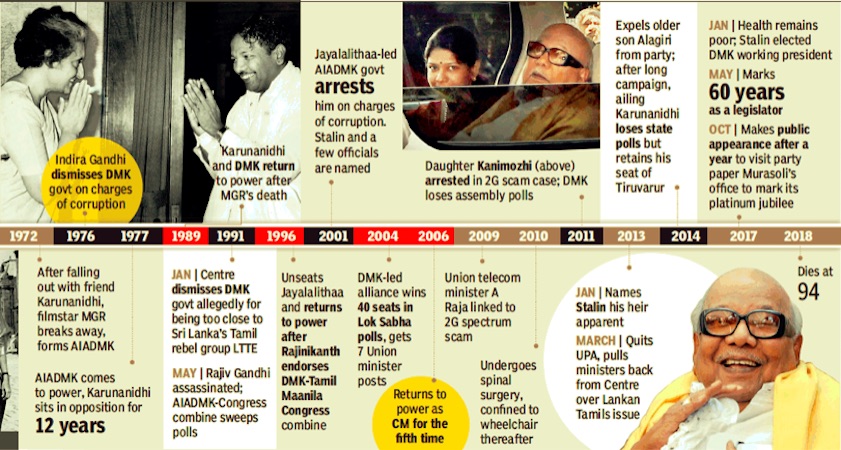

[edit] A significant role in coalition governments, 1977-2016

From: R Kannan, M Karunanidhi: Dravidian satrap who aced the game of coalition politics June 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: R Kannan, M Karunanidhi: Dravidian satrap who aced the game of coalition politics June 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: R Kannan, M Karunanidhi: Dravidian satrap who aced the game of coalition politics June 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: R Kannan, M Karunanidhi: Dravidian satrap who aced the game of coalition politics June 4, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Karunanidhi, a regional leader who made himself indispensable to India’s national political trajectory from the late 1960s until recently.

Be it helping Indira Gandhi to consolidate power, facilitating national alliances or extending support to the NDA and the UPA, Karunanidhi hands were seen in nationally momentous occasions.

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

From: August 8, 2018: The Times of India

On February 10, 1969 Karunanidhi stepped into C N Annadurai’s large shoes as chief minister. "I have heard that he is a confrontationist," Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had remarked then. But Karunanidhi didn’t let his Dravidian credentials stanch his ambitions for the DMK.

Hedging his bets carefully, he became the first chief minister to advocate bank nationalisation in 1969. It was a clever move. The Congress’ old guard was opposed to the idea and Indira Gandhi, who was yet to consolidate her position, was not too sure about such a gamble. But, Karunanidhi had sensed that Gandhi would emerge victorious in the intra-Congress fight for power and that a regional satrap pronouncing such a national policy was strategic. As Karunanidhi himself recalled later in 1994, the DMK with its feet firmly in Tamil Nadu, "had extended its hands nationally." On July 19, 1969, Indira Gandhi announced bank nationalisation. She was an ally of the same "confrontationist" Karunanidhi.

This was Karunanidhi, a regional leader who made himself indispensable to India’s national political trajectory from the late 1960s until recently. Be it helping Indira Gandhi to consolidate power, facilitating national alliances or extending support to the NDA and the UPA, his hands were seen in nationally momentous occasions.

To weaken Kamaraj’s potently strong Congress in Tamil Nadu, Karunanidhi helped build the breakaway Congress faction led by Indira Gandhi. He stood by Gandhi when she chose to field her own presidential candidate in 1969 against the official candidate. His talks with the chief ministers of Punjab and West Bengal led to a consensus and Karunanidhi made the official announcement on V V Giri’s candidacy in Madras.

After the DMK’s victory in the 1971 elections, Karunanidhi articulating the party’s goals for stronger states, on 29 March 1971, said "I believe no one in India would wish to create a Mujibur Rahman in each state." Meanwhile, he joined hands with the opposition and addressed a social justice conference in 1973 in the north. This, he records, was resented in Delhi.

The split in the DMK by MGR in 1972 was a major political setback. But the worst was yet to come. During Emergency (1975), the DMK government was dismissed, more than four hundred DMK cadres were interned and DMK leaders feared that the party would be banned. Among the arrested was Karunanidhi’s son M K Stalin and nephew Murasoli Maran.

Karunanidhi’s opposition to Emergency built bridges to Jayaprakash Narayan. In the post-Emergency period, he would host leaders from the north in Delhi – a meeting that led to the birth of Janata Party that felled Indira Gandhi in 1977. The Janata experiment, however, turned out to be a huge disappointment. The DMK later joined hands with the Congress in 1980, only to part ways in 1983 over the Sri Lankan Tamils issue

Karunanidhi’s relationship with the opposition was such that he could bring N T Rama Rao and A B Vajpayee under the banner of the Tamil Eelam Supporters Organisation (TESO) in Madurai in May 1985, to show solidarity with the Sri Lankan Tamils.

When V P Singh broke company with Rajiv Gandhi, Karunanidhi rallied behind Singh, playing a substantial role in the formation of the National Front. The implementation of the Mandal Commission, the return of the Indian Peacekeeping Forces and the constitution of the Cauvery Tribunal should all be credited to Karunanidhi’s friendship with Singh.

After Singh’s exit, Karunanidhi was instrumental in the choice of Deve Gowda and I K Gujral as prime ministers. In 1999, he propped up the National Democratic Alliance government led by the BJP’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee. The coalition helped in TN’s development, but he deftly ended the relationship in 2004 sensing it as a political liability. Soon he was one of the driving forces behind the United Progressive Alliance led by Sonia Gandhi. In return Sonia Gandhi treated Karunanidhi as their alliance’s Bhishma, and at one-point Tamil Nadu had the highest contingent of ministers. But, in March 2013 the DMK pulled out of the UPA government.

It is amazing that Karunanidhi, a high school dropout with no knowledge of Hindi, had often taken centre stage nationally and moved with ease with northern leaders. But then he himself is no ordinary leader. A stage artist, script writer, speaker, organiser, poet, administrator and journalist — Karunanidhi is an extraordinarily endowed leader. And at 94 he stills remains one.

(The writer is the deputy head of the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia’s Hirshabelle office)

[edit] Reminiscences of those who worked with him

R Poornalingam | Former Home Secretary

'Wanted tomorrow's work yesterday'

While it was a pleasure to work with Mr K, it was equally tough and demanding. He would expect tomorrow's work to be executed yesterday. For that, he worked so hard that no one could meet his expectation.

He was always willing to listen to differing points of view. Once he was deciding on the case of a political nuisance maker, when I, as the home secretary, was present. A few minutes after his decision, he could see I was not agreeing with him. He asked my views, which were opposite to his; not only did he agree with me, but also immediately countermanded his orders.

Another incident that touched me was when I was the chairman of Tamil Nadu Electricity Board. The board had increased the new connection charges from Rs 350 to Rs 1,000. When the electricity demand was being discussed in the assembly, the opposition objected to the sharp increase. The CM walked up to the officers' gallery and asked me whether the amount could be reduced to Rs 500. Naturally I was reluctant, but he bargained with me and settled for a reduction of Rs 300. There was absolutely no need for him to consult me. As the CM, he could have simply announced. It is his willingness to respect his subordinate's views which was touching.

K Thirunavukarasu | Dravidian historian

Never compromised

During Emergency, where there was a lot of pressure from the Centre on him as chief minister of Tamil Nadu to do certain things, Thalaivar refused to compromise. As a result many DMK leaders were arrested and sent to prison for nearly a year.

One of the demands on all state parties was to change their party names either to add India at the start or at the end. It was during this period that AIADMK founder M G Ramachandran changed the name of his party from Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam to All India ADMK.

Within DMK too, many senior leaders asked Thalaivar to change the name of the party and make it an allIndia party. But Thalaivar refused. He said DMK was founded by C N Annadurai for the sake of Tamil people and culture. He refused to change the party's name and said he was ready to face anything from the Centre.

Kamal Haasan | Actor

When I got in character to pose

When I was acting in `Sattam En Kayil' (1978), director T N Baalu told Kalaignar about me. During the 100-day celebration of the film, I got an opportunity to sit next to Kalaignar. Whenever I acted in a good film, I always longed to screen it for Kalaignar. Our relationship grew stronger to the point that when I did not show him my film, he would ask me why. The high point was when I went to his home dressed as the `Avvai Shanmughi' character and posed for photos with him. After watching `Dasavatharam' (2008), he pinched my cheeks in appreciation. When I was writing 'Dasavatharam', he suggested several ideas. He is not just a senior political leader or a Tamil scholar, but also a wonderful screenplay and dialogue writer.

Once, on his birthday, he asked me why I had not visited him and told me that he did not have a lot of time left. I told him there was time and that I would visit him. This was when he was 84, now he is 94. Vazhga Kalaingar (long live Kalaignar)

K Veeramani | Dravidian Kazhagam president

Those days of our youth

My relationship with DMK president M Karunanidhi goes back 70 years, when we were students. During summer holidays we used to join Periyar's training school in Erode and once, after a function, we stayed over at a member's house in a village near Thiruthuraipoondi, in undivided Thanjavur district. We were both tired but mosquitoes kept Karunanidhi awake, while I slept through it. Around 1am, he woke me up and said he wanted to leave for the next stop Thiruthuraipoondi.In the dead of the night; we found an open bullock cart and along with two others set off. We reached our friend's house in Thiruthuraipoondi at 3am. But not wanting to wake him up, slept on the sitouts. In the morning when the householders found us on the sit-outs they were astonished. Another time he attended a Periyar conference near Trichy when he had small pox.

Raadhika Sarathkumar | Actor

Challenged to get the best

I acted in many films written by Kalaignar including `Paasa Paravaigal' (1988) which had difficult dialogues.When I was practising the lines for a court scene in the film, I noticed he had a note for me in the script that read, "If Raadhika finds these lines difficult to recite, please change it to suit her". I thought I should do better than what he would have expected. The dialogue was long and had to be taken in one shot. I delivered it with a slight change. I think he was challenging me through the note to ace it and I did. When he spoke about it on stage years later, he said, "There is not much Raadhika cannot do, I penned the lines with the confidence that she will deliver."

Away from the arc lights, I have seen Kalaignar when he won and lost elections.In the 2001 TN assembly elections DMK suffered a humiliating defeat. I was at his Gopalapuram residence when the election results came out. He remained silent for 10 minutes then he went around consoling party members.

Lyricist Vairamuthu remembers this indomitable spirit when the Centre dismissed the DMK government in 1991.When the news reached the leadership; the ministers were dejected and asked Kalaignar to cancel a scheduled conference of the state teachers association. I was there when Kalaignar told his party men, "It is now that we have to meet the people more than ever."