Jainism/ Jain Religion

(→Anekant) |

|||

| Line 248: | Line 248: | ||

=Anekant= | =Anekant= | ||

| + | ==A Lotus Of Many Layered Petals== | ||

[http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=the-speaking-tree-Anekanta-Lotus-Of-Many-Layered-20042016022091 ''The Times of India''], Apr 20 2016 | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=the-speaking-tree-Anekanta-Lotus-Of-Many-Layered-20042016022091 ''The Times of India''], Apr 20 2016 | ||

Revision as of 16:01, 12 December 2018

The first section was written in 1916 when conditions were different. Even in Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook |

From The Tribes And Castes Of The Central Provinces Of India

By R. V. Russell

Of The Indian Civil Service

Superintendent Of Ethnography, Central Provinces

Assisted By Rai Bahadur Hira Lal, Extra Assistant Commissioner

Macmillan And Co., Limited, London, 1916.

NOTE 1: The 'Central Provinces' have since been renamed Madhya Pradesh.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from the original book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot these footnotes gone astray might like to shift them to their correct place.

Contents |

Jain Religion

[^Bibliography : The Jainas, by Dr. J. G. Buhler and J. Burgess, London, 1903; The Religions of India, Professor E. W. Hopkins; 7/^1? Religions of India, Professor A. Barth ; Punjab Census Report (1891), Sir E. D. Maclagan ; article on Jainism in Dr. Hastings' Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics.^ LIST OF PARAGRAPHS

1. Numbers atid dtstribi(tio?i. 8. Jam subcastes of Banias. 2. The Jain religion. Its connee- 9. Rules ajid customs of ihe laity. tio7i with Buddhism. 10. Connectio7i with Hinduism. 3. TheJain tenets. The Tirthakdrs. 11. Temples and carfestival. 4. The transmigratio?! of souls. 12. Images of the Tirthakdrs. 5. Strict rules against taking life. 13. Religious observances. b. Jain sects. 14. Tetiderness for animal life, y. Jain ascetics. 15. Social condition of the Jains.

Jain

The total number of Jains in the Central Provinces i. Num- in 191 I was 71,000 persons. They nearly all belong to the |i|'s\ribu^ Bania caste, and are engaged in moneylending and trade tion. like other Banias. They reside principally in the Vindhyan Districts, Saugor, Damoh and Jubbulpore, and in the principal towns of the Nagpur country and Berar. The Jain tenets present marked features of resemblance 2. The to Buddhism, and it was for some time held that Jainism J^'"*"^'- was merely a later offshoot from that religion.

The more its connec- generally accepted view now, however, is that the Jina or buddhism, prophet of the Jains was a real historical personage, who lived in the sixth century B.C., being a contemporary of Gautama, the Buddha. Vardhamana, as he was commonly called, is said to have been the younger son of a small chieftain in the province of Videha or Tirhut. Like Sakya- Muni the Buddha or enlightened, Vardhamana became an ascetic, and after twelve years of a wandering life he appeared as a prophet, proclaiming a modification of the

doctrine of his own teacher Parsva or Parasnath. From this time he was known as Mahavira, the great hero, the same name which in its famiHar form of Mahablr is appHed to the god Hanuman. The title of Jina or victorious, from which the Jains take their name, was subsequently conferred on him, his sect at its first institution being called Nirgrantha or ascetic. There are very close resemblances in the tradi- tions concerning the lives of Vardhamana and Gautama or Buddha. Both were of royal birth ; the same names recur among their relatives and disciples ; and they lived and preached in the same part of the country, Bihar and Tirhijt.^ Vardhamana is said to have died during Buddha's lifetime, the date of the latter's death being about 480 B.C.^

Their doctrines also, with some important differences, present, on the whole, a close resemblance. Like the Buddhists, the Jains claim to have been patronised by the Maurya princes. While Asoka was mainly instrumental in the propagation of Buddhism over India, his grandfather Chandragupta is stated to have been a Jain, and his grandson Sampadi also figures in Jain tradition, A district which is a holy land for one is almost always a holy land for the other, and their sacred places adjoin each other in Bihar, in the peninsula of Gujarat, on Mount Abu in Rajputana and elsewhere.^

The earliest of the Jain books belongs to the sixth century A.D., the existence of the Nirgrantha sect in Buddha's life- time being proved by the Cingalese -books of the Buddhists, and by references to it in the inscriptions of Asoka and others."* While then M. Barth's theory that Jainism was simply a later sect of Buddhism has been discarded by subsequent scholars, it seems likely that several of the details of Vardhamana's life now recorded in the Jain books are not really authentic, but were taken from that of Buddha with necessary alterations, when the true facts about their own prophet had been irrevocably lost. 3. The Like the Buddhists, the Jains recognise no creator of Jain tenets, j-j^^ world, and supposc it to have existed from eternity. Tirthakars. Similarly, they had originally no real god, but the Jina or 1 Barth, p. 148. " Earth, p. 149- 2 Hopkins, p. 310, and Tlie Jains, * Tlie Jaiitas, pp. 38-47. p. 40.

victor, like the jainBuddha or Enlightened One, was held to have been an ordinary mortal man, who by his own pcnvcr had attained to omniscience and freedom, and out of pity for suffering mankind preached and declared the way of salvation which he had found.^ This doctrine, however, was too abstruse for the people, and in both cases the prophet himself gradually came to be deified, l-'urther, in order perhaps to furnish objects of worship less distinctively human and to whom a larger share of the attributes of deity could be imputed, in both religions a succession of mythical predecessors of the prophet was gradually brought into existence.

The Buddhists recognise twenty-five Buddhas or divine prophets, who appeared at long epochs of time and taught the same system one after another ; and the Jains have twenty-four Tirthakars or Tirthankars, who similarly taught their religion. Of these only Vardhamana, its real founder, who was the twenty-fourth, and possibly Parsva or Parasnath, the twenty-third and the founder's preceptor, are or may be historical. The other twenty-two Tirthakars are purely mythical.

The first, Rishaba, was born more than 100 billion years ago, as the son of a king of Ajodhya ; he lived more than 8 million years, and was 500 bow-lengths in height. He therefore is as superhuman as any god, and his date takes us back almost to eternity. The others succeeded each other at shorter intervals of time, and show a progressive decline in stature and length of life. The images of the Tirthakars are worshipped in the Jain temples like those of the Buddhas in Buddhist temples. As with Ikiddhism also, the main feature of Jain belief is the trans- migration of souls, and each successive incarnation depends on the sum of good and bad actions or karinan in the previous life.

They hold also the primitive animistic doctrine that souls exist not only in animals and plants but in stones, lumps of earth, drops of water, fire ami wind, and the human soul ma}- pass even into these if its sins condemn it to such a fate." The aim which Jainism, like l^uddhism, sets before its i- I'le disciples is the escape from the endless round of successive m'igration .of souls. ' The writer is inclined to doubt theism ; but the above is the view of whether either Buddhism or Jainism the best authorities. were really atheistic, and to think that they were perhaps rather forms of pan- ^ I'he Jaiitas, \i. 10.

existences, known as Samsara, through the extinction of the karman or sum of actions. This is attained by complete subjection of the passions and destruction of all desires and appetites of the body and mind, that is, by the most rigid asceticism, as well as by observing all the moral rules pre- scribed by the religion.

It was the J In a or prophet who showed this way of escape, and hence he is called Tirthakar or * The Finder of the Ford,' through the ocean of existence.^ But Jainism differs from Buddhism in that it holds that the soul, when finally emancipated, reaches a heaven and there continues for ever a separate intellectual existence, and is not absorbed into Nirvana or a state of blessed nothingness. 5 Strict The moral precepts of the Jains are of the same type as rules those of Buddhism and Vaishnavite Hinduism, but of an taking life, excessive rigidity, at any rate in the case of the Yatis or Jatis, the ascetics. They promise not to hurt, not to speak un- truths, to appropriate nothing to themselves without per- mission, to preserve chastity and to practise self-sacrifice. But these simple rules are extraordinarily expanded on the part of the Jains.

Thus, concerning the oath not to hurt, on which the Jains lay most emphasis : it prohibits not only the intentional killing or injuring of living beings, plants or the souls existing in dead matter, but requires also the utmost carefulness in the whole manner of life, and a watchfulness also over all movements and functions of the body by which anything living might be hurt.

It demands, finally, strict watch over the heart and tongue, and the avoid- ance of all thoughts and words which might lead to disputes and quarrels, and thereby do harm. In like manner the rule of sacrifice requires not only that the ascetic should have no houses or possessions, but he must also acquire a complete unconcern towards agreeable or disagreeable im- pressions, and destroy all feelings of attachment to anything living or dead." Similarly, death by voluntary starvation is prescribed for those ascetics who have reached the Kewalin or brightest stage of knowledge, as the means of entering their heaven. Owing to the late date of the Jain scriptures, any or all of its doctrines may have been adopted from l^uddhism between the commencement of the two religions

and the time when they were compiled. The Jains did not definitely abolish caste, and hence escaped the persecution to which Buddhism was subjected during the period of its decline from the fifth or sixth century A.i). On account of this trouble many Buddhists became Jains, and hence a further fusion of the doctrines of the rival sects may have ensued. The Digambara sect of Jains agree with the Buddhists in holding that women cannot attain Nirvana or heaven, while the Swetambara sect say that they can, and also admit women as nuns into the ascetic order. The Jain scripture, the Yogashastra, speaks of women as the lamps that burn

on the road that leads to the gates of hell.

The Jains are divided into the above two principal sects, 6. Jain the Digambara and the Swetambara. The Digambara are ^'^'^'^' the more numerous and the stricter sect. According to

their tenets death by voluntary starvation is necessary for ascetics who would attain heaven, though of course the rule is not now observed. The name Digambara signifies sky-clad, and Swetambara white - clad. Formerly the Digambara

ascetics went naked, and were the gymnosophists of the Greek writers, but now they take off their clothes, if at all, only at meals. The theory of the origin of the two sects is

that Parasnath, the twenty-third Tirthakar, wore clothes,

while Mahavira the twenty-fourth did not, and the two sects follow their respective examples. The Digambaras now wear ochre-coloured cloth, and the Swetambaras white.

The principal difference at present is that the images in Digambara temples are naked and bare, while those of the Swetambaras are clothed, presumably in white, and also decorated with jewellery and ornaments. The Digambara ascetics may not use vessels for cooking or holding their food, but must take it in their hands from their disciples and eat it thus ; while the Swetambara ascetics may use vessels. The Digambara, however, do not consider the straining-cloth, brush, and gauze before the mouth essential to the character of an ascetic, while the Swetambara insist on them. There is in the Central Provinces another small sect called Channagri or Samaiya, and known elsewhere as Dhundia. These do not put images in their temples at all, but only copies of the Jain sacred books, and pay reverence

to them. They will, -however, worship in regular Jain temples at places where there are none of their own. 7. Jain The initiation of a Yati or Jati, a Jain ascetic, is thus ascetics, described : It is frequent for Banias who have no children to vow that their first-born shall be a Yati. Such a boy serves a novitiate with a guru or preceptor, and performs for him domestic offices ; and when he is old enough and has made progress in his studies he is initiated. P'or this purpose the novice is carried out of the tower with music and rejoicing in procession, followed by a crowd of Sravakas or Jain laymen, and taken underneath the banyan, or any other tree the juice of which is milky.

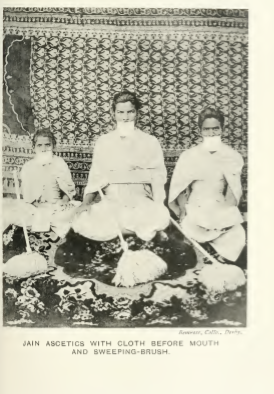

His hair is pulled out at the roots with five pulls ; camphor, musk, sandal, saffron and sugar are applied to the scalp ; and he is then placed before his guru, stripped of his clothes and with his hands joined. A text is whispered in his ear by the guru, and he is invested with the clothes peculiar to Yatis ; two cloths, a blanket and a staff; a plate for his victuals and a cloth to tie them up in ; a piece of gauze to tie over his mouth to prevent the entry of insects ; a cloth through which to strain his drinking-water to the same end ; and a broom made of cotton threads or peacock feathers to sweep the ground before him as he walks, so that his foot may not crush any living thing.

The duty of the Yati is to read and explain the sacred books to the Sravakas morning and evening, such functions being known as Sandhya. His food consists of all kinds of grain, vegetables and fruit produced above the earth ; but no roots such as yams or onions. Milk and g/il are permitted, but butter and honey are prohibited. Some strict Yatis drink no water but what has been first boiled, lest they should inadvertently destroy any insect, it being less criminal to boil them than to destroy them in the drinker's stomach. A Yati having renounced the world and all civil duties can have no family, nor does he perform any office of mourning or rejoicing.^ A Yati was directed to travel about begging and preaching for eight months in the year, and during the four rainy months to reside in some village or town and observe a fast. The rules of conduct to be observed by him were extremely

Beinrosc, Collp., Derby. JAIN ASCETICS WITH CLOTH BEFORE MOUTH AND SWEEPING-BRUSH.

strict, as has already been seen. Those who observed them successfully were believed to acquire miraculous powers. He who was a Siddh or victor, and had overcome his Karma or the sum of his human actions and affections, could read the thoughts of others and foretell the future. He who had attained Kewalgyan, or the state of perfect knowledge which preceded the emancipation of the soul and its absorption into paradise, was a god on earth, and even the gods worshipped him. Wherever he went all plants burst into flower and brought forth fruit, whether it was their season or not. In his presence no animal bore enmity to another or tried to kill it, but all animals lived peaceably together. This was the state attained to by each Tirthakar during his last sojourn on earth. The number of Jain ascetics seems now to be less than formerly and they are not often met with, at least in the Central Provinces. They do not usually perform the function of

temple priest.

Practically all the Jains in the Central Provinces are of s. Jain the Bania caste. There is a small subcaste of Jain Kalars, subcastes •' 'of Banias. but these are said to have gone back to Hinduism. Of the Bania subcastes who are Jains the principal are the Parwar, Golapurab, Oswal and Saitwal. Saraogi, the name for a Jain layman, and Charnagar, a sect of Jains, are also returned as subcastes of Jain Banias. Other important subcastes of Banias, as the Agarwal and Maheshri, have a Jain section. Nearly all Banias belong to the Digambara sect, but the Oswal are Swetambaras.

They are said to have been originally Rajpiits of Os or Osnagar in Rajputana, and while they were yet Rajputs a Swetambara ascetic sucked the poison from the wound of an Oswal boy whom a snake had bitten, and this induced the community to join the Swetambara sect of the Jains."' The Jain laity are known as Shrawak or Saraogi, learners. 9. Rules There is comparatively little to distinguish them from their ^^g^J^^g oc Hindu brethren. Their principal tenet is to avoid the the laity,

destruction of all animal, including insect life, but the Hindu Banias are practically all Vaishnavas, and observe

lo. Con-

nection

with Hinduism.

almost the same tenderness for animal life as the Jains. The Jains are distinguished by their separate temples and method of worship, and they do not recognise the authority of the Vedas nor revere the lingajii of Siva. Consequently they do not use the Hindu sacred texts at their weddings, but repeat some verses from their own scriptures. These weddings arc said to be more in the nature of a civil contract than of a religious ceremony. The bride and bridegroom walk seven times round the sacred post and are then seated on a platform and promise to observe certain rules of conduct towards each other and avoid offences. It is said that formerly a Jain bride was locked up in a temple for the first night and considered to be the bride of the god. But as scandals arose from this custom, she is now only locked up for a minute or two and then let out again. Jain boys are in- vested with the sacred thread on the occasion of their weddings or at twenty-one or twenty-two if they are still unmarried at that age.

The thread is renewed annually on the day before the full moon of Bhadon (August), after a ten days' fast in honour of Anant Nath Tirthakar. The thread is m.ade by the Jain priests of tree cotton and has three knots. At their funerals the Jains do not shave the moustaches off as a rule, and they never shave the choti or scalp-lock, which they wear like Hindus. They give a feast to the caste- fellows and distribute money in charity, but do not perform the Hindu sJirdddJi or offering of sacrificial cakes to the dead. The Agarwal andKhandelwal Jains, however, invoke the spirits of their ancestors at weddings. Traces of an old hostility be- tween Jains and Hindus survive in the Hindu saying that one should not take refuge in a Jain temple, even to escape from a mad elephant ; and in the rule that a Jain beggar will not take alms from a Hindu unless he can perform some service in return, though it may not equal the value of the alms.

In other respects the Jains closely resemble the Hindus. Brahmans are often employed at their weddings, they reverence the cow, worship sometimes in Hindu temples, go on pilgrim- ages to the Hindu sacred places, and follow the Hindu law of inheritance. The Agarwal Bania Jains and Hindus will take food cooked with water together and intermarry in Ikjndclkhand, although it is doubtful whether they do this

in the Central Provinces. In such a case each party pays a fine to the Jain temple fund. In respect of caste distinctions the Jains are now scarcely less strict than the Hindus. The different Jain subcastes of Banias coming from Bundelkhand will take food together as a rule, and those from Marwar will do the same. The Khandelwal and Oswal Jain Banias will take food cooked with water together when it has been cooked by an old woman past the age of child-bearing, but not that cooked by a young woman.

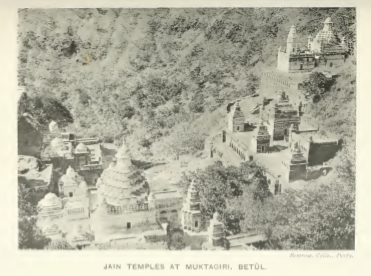

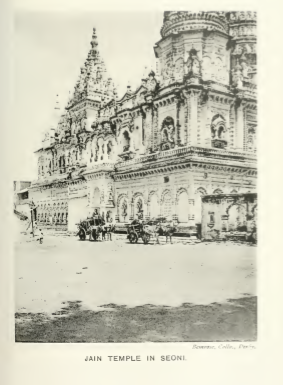

The spread of educa- tion has awakened an increased interest among the Jains in their scriptures and the tenets of their religion, and it is quite likely that the tendency to conform to Hinduism in caste matters and ceremonies may receive a check on this account.^ The Jains display great zeal in the construction of temples n. in which the images of the Tirthakars are enshrined. The '^'-"P^'^^ and car • temples are commonly of the same fashion as those of the festival. Hindus, with a short, roughly conical spire tapering to a point at the apex, but they are frequently adorned with rich carved stone and woodwork. There are fine collections of temples at Muktagiri in Betul, Kundalpur in Damoh, and at Mount Abu, Girnar, the hill of Parasnath in Chota Nagpur, and other places in India. The best Jain temples are often found in very remote spots, and it is suggested that they were built at times when the Jains had to hide in such places to avoid Hindu persecution. And wherever a community of Jain merchants of any size has been settled for a generation or more several fine temples will probably be found.

A Jain Bania who has grown rich considers the building of one or more temples to be the best method of expending his money and acquiring religious merit, and some of them spend all their fortune in this manner before their death. At the opening of a new temple the ratli or chariot festival should be held. Wooden cars are made, sometimes as much as five stories high, and furnished with chambers for the images of the Tirthakars. In these the idols of the hosts and all the guests are placed. Each car should be drawn by two elephants, and the pro- cession of cars moves seven times round the temple or pavilion erected for the ceremony. For building a temple 1 Mr. Marten's Central Provinces Census Report, 191 1. of the Tirthakars

and performing this ceremony honorary and hereditary titles are conferred. Those who do it once receive the designation of Singhai ; for carrying it out twice they become Sawai Singhai ; and on a third occasion Seth. In such a ceremony performed at Khurai in Saugor one of the participators was already a Seth, and in recognition of his great liberality a new title was devised and he became Srimant Seth.

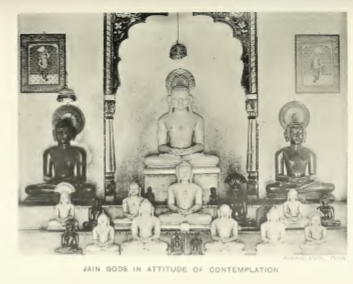

It is said, however, that if the car breaks and the elephants refuse to move, the title becomes derisive and is either ' Lule Singhai,' the lame one, or ' Arku Singhai,' the stumbler. If no elephants are available and the car has to be dragged by men, the title given is Kadhore Singhai. Images In the temples are placed the images of Tirthakars, either of brass, marble, silver or gold. The images may be small or life-size or larger, and the deities are represented in a sitting posture with their legs crossed and their hands lying upturned in front, the right over the left, in the final attitude of contemplation prior to escape from the body and attain- ment of paradise.

There may be several images in one temple, but usually there is only one, though a number of temples are built adjoining each other or round a courtyard. The favourite Tirthakars found in temples are Rishab Deva, the first; Anantnath, the fourteenth; Santnath, the sixteenth; Nemnath, the twenty-second ; Parasnath, the twenty-third ; and Vardhamana or Mahavira, the twenty-fourth.^ As already stated only Mahavira and perhaps Parasnath, his preceptor, were real historical personages, and the remainder are mythical. It is noticeable that to each of the Tirthakars is attached a symbol, usually in the shape of an animal, and also a tree, apparently that tree under which the Tirthakar is held to have been seated at the time that he obtained release from the body. And these animals and trees are in most cases those which are also revered and held sacred by the Hindus.

Thus the sacred animal of Rishab Deva is the bull, and his tree the banyan ; that of Anantnath is the falcon or bear, and his tree the holy Asoka ; " that of Santnath is the black-buck or Indian antelope, and his tree the tun or cedar ; ^ the symbol of Nemnath is the conch ' The particulars about the Tirthakars and the animals and trees associated with them are taken from The Jainas. - Jonesia Asoka. ^ Qedrela (oona.

shell (sacred to Vishnu), but his tree, the vciasa, is not known ; the animal of Parasnath is the serpent or cobra and his tree the dhdtaki ; ^ and the animal of Mahfivlra is the lion or tiger and his tree the teak tree. Among the symbols of the other Tirthakars are the elephant, horse, rhinoceros, boar, ape, the Brahmani duck, the moon, the pipal tree, the lotus and the swasiik figure ; and among their trees the mango, \.\\Q jdviun'^ and the chaiiipak? Most of these animals and trees are sacred to the Hindus, and the elephant, boar, ape, cobra and tiger were formerly worshipped themselves, and are now attached to the principal Hindu gods. Similarly the asoka, pipal, banyan and mango trees are sacred, and also the Brahmani duck and the swastik sign.

It cannot be supposed that the Tirthakars simply represent the deified anthropomorphic emanations from these animals, because the object of Vardhamana's preaching was perhaps like that of Buddha to do away with the promiscuous polytheism of the Hindu religion. But nevertheless the association of the sacred animals and trees with the Tirthakars furnished a strong connecting link between them and the Hindu gods, and considerably lessens the opposition between the two systems of worship. The god Indra is also frequently found sculptured as an attendant guardian in the Jain temples. The fourteenth Tirthakar, Anantnath, is especially revered by the people because he is identified with Gautama Buddha. The priest of a Jain temple is not usually a Yati or 13. Reiigi- ascetic, but an ordinary member of the community. He receives no remuneration and carries on his business at the same time.

He must know the Jain scriptures, and makes recitations from them when the worshippers are assembled. The Jain will ordinarily visit a temple and see the god every morning before taking his food, and his wife often goes with him. If there is no temple in their own town or village they will go to another, provided that it is within a practicable distance. The offerings made at the temple consist of rice, almonds, cocoanuts, betel-leaves, areca, dates, cardamoms, cloves and similar articles. These are appropriated by the Hindu Mali or gardener, who is the menial servant em- 1 Griska tomeutosa. ^ Eitgeiiia jambolana. 3 Michelia champaka. ous observ-

ployed to keep the temple and enclosures clean.

The Jain will not take back or consume himself anything which has been offered to the god. Offerings of money are also made, and these go into the bhanddr or fund for maintenance of the temple.

The Jains observe fasts for the last week before the new moon in the months of Phagun (February), Asarh (June) and Kartik (October). They also fast on the second, fifth, eighth, eleventh and fourteenth days in each fortnight of the four months of the rains from Asarh to Kartik, this being in lieu of the more rigorous fast of the ascetics during the rains. On these days they eat only once, and do not eat any green vegetables. After the week's fast at the end of Kartik, at the commencement of the month of Aghan, the Jains begin to eat all green vegetables. 14, Ten- The great regard for animal life is the most marked animal life, feature of the Jain religion among the laity as well as the clergy. The former do not go to such extremes as the latter, but make it a practice not to eat food after sunset or before sunrise, owing to the danger of swallowing insects.

Now that their beliefs are becoming more rational, however, and the irksome nature of this rule is felt, they sometim.es place a lamp with a sieve over it to produce rays of light, and consider that this serves as a substitute for the sun. For- merly they maintained animal hospitals in which all kinds of animals and reptiles, including monkeys, poultry and other birds were kept and fed, and any which had broken a limb or sustained other injuries were admitted and treated.

These were known as pinjrapol or places of protection.^ A similar institution was named jivuti, and consisted of a small domed building with a hole at the top large enough for a man to creep in, and here weevils and other insects which the Jains might find in their food were kept and pro- vided with grain.' In Rajputana, where rich Jains probably had much influence, considerable deference was paid to their objections to the death of any living thing. Thus a Mewar edict of A.D. 1693 directed that no one might carry animals for slaughter past their temples or houses. Any man or ' Crooke, Things Indian, art. Pinjrapol. - Moor, Hindu Infanticide, p. 1S4. rase, Collo., Derhy.

animal led past a Jain house for the purpose of being killed was thereby saved and set at liberty. Traitors, robbers or escaped prisoners who fled for sanctuary to the dwelling of a Jain Yati or ascetic could not be seized there by the officers of the court.

And during the four rainy months, when insects were most common, the potter's wheel and Teli's oil- press might not be worked on account of the number of insects which would be destroyed by them.^ As they are nearly all of the Bania caste the Jains are 15. Social usually prosperous, and considering its small size, the standard '^o"^'"°" of wealth in the community is probably very high for India, Jains, the total number of Jains in the country being about half a million. Beggars are rare, and, like the Parsis and Europeans, the Jains feeling themselves a small isolated body in the midst of a large alien population, have a special tenderness for their poorer members, and help them in more than the ordinary degree.

Most of the Jain Banias are grain-dealers and moneylenders like other Banias. Cultivation is pro- hibited by their religion, owing to the destruction of animal life which it involves, but in Saugor, and also in the north of India, many of them have now taken to it, and some plough with their own hands. Mr. Marten notes " that the Jains are beginning to put their wealth to a more practical purpose than the lavish erection and adornment of temples.

Schools and boarding-houses for boys and girls of their

religion are being opened, and they subscribe liberally for the building of medical institutions. It may be hoped that this movement will continue and gather strength, both for the advantage of the Jains themselves and the country

generally.

1 Rdjasthdn, vol. i. p. 449, and pp. 696, 697, App. 2 Central Provimes CeJistis Report, 191 1.

Anekant

A Lotus Of Many Layered Petals

The Times of India, Apr 20 2016

Sudhamahi Regunathan

Anekanta: Lotus Of Many Layered Petals According to Jaina metaphysics, it is matter that defines existence.

Every object has an origin. For example, a pot has its origin in clay. One day the pot breaks. That marks the end of the pot. But that which is permanent is the clay with which the pot was made.That remains.

What remains as it is and does not pass away is eternal. We are born, we die, but the permanent aspect, our soul, lives on to be born again or liberated.The dravya or matter, which is the clay in the example of the pot, is permanent.That which is nitya or permanent is dravya. That which is anitya or impermanent is paryaya or a mode. The Tatvartha Sutra defines dravya in the following manner: `That which possesses qualities and modes is a substance.' According to Mahavira, the fundamental substances are the pancha astikayas or five `collective groups' or `extended substances'. These five substances are: dharma astikaya, adharma astikaya, akash astikaya, jiva astikaya and pudgal astikaya. The Tatvartha Sutra says some teachers also consider time to be the sixth astikaya.

Dharma astikaya is the medium that facilitates all movement in this world.And yet, you have to stop typing periodically to refer, to correct, to think, to erase, to take a break.If dharma astikaya alone were in operation, you would never be able to stop. Adharma astikaya is the medium of rest.It is because of the collection of atoms belonging to the adharma astikaya variety that you are able to stop when you wish to.

The akash astikaya is space consisting of two sections loka or this universe and aloka or space outside this universe. These three astikayas do not change. The variety in the world owes itself to pudgal astikaya and jiva astikaya.

That is the contention of anekanta: the source as the permanent, creation and destruction as constant, ongoing processes.

Of course, the question will not be late in coming: What is the distinguishing feature of the soul? The soul has consciousness, which matter does not have. Soul has knowledge: `Je aaya se vinnayya, je vinnayya se ayya' the soul knows, the knower is the soul. Karmic material, matter that adheres to the soul, is associated with form and colour.

The Tatvartha Sutra goes on to say, `Arpita narpita-siddheh' the ungrasped (unnoticed) aspect of an object is attested by the grasped (noticed) one. This is a beautiful sutra. How would you know something was ugly? Because you know it is not beautiful.How would you know there is silence? Because there is no sound. Opposites are integral to the whole. Coexistence of opposites is the principle of anekanta. Darkness is understood only because of light.

This brings us to the next idea inherent in the principle of anekanta: the dominance of one aspect at any given time. In a given situation, when objects have infinite attributes, one of them will be primary and the rest, secondary . One attribute will be manifest while others will be unmanifest.In nature, a similar situation exists; when man walks, the rule is one foot goes ahead and the other follows.

Since truth is multidimensional, it is not possible for us to comprehend it all.

Anekanta is like a lotus; although its petals are laid out in many layers, they form a single flower. It embodies different concepts complete with their partners in opposites.