Pakistani Hindus in India

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

(→Why Hindus leave Pakistan for India) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

[[Category:Pakistan |H ]] | [[Category:Pakistan |H ]] | ||

[[Category:Communities |P ]] | [[Category:Communities |P ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Why Hindus leave Pakistan for India= | ||

| + | ==As in 2019== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/why-pakistani-hindus-leave-their-homes-for-india/articleshow/68628244.cms Anam Ajmal, April 4, 2019: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''The refugees live in makeshift houses and tents in Delhi. Despite the lack of infrastructure, they say they have found ‘freedom” here. The decision to leave their home was not easy but they were left with no option'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Almost every family living in the two refugee colonies in the capital for Hindus from Pakistan has a story to tell on what impelled them to leave their homes and flee to India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dharmu ‘Master’, a tailor in his early-40s, came to India in 2017. His wife and three children took the only train — Thar Express — from his village in Sindh and got down at Jodhpur in Rajasthan before coming to Delhi. “We got a visa to visit Haridwar. But while leaving our house in Pakistan, we knew we would not return again,” says Dharmu. “I had an established business there but we had to leave because we were being targeted by our neighbours.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Trouble started in 2016 when Dharmu opened a new shop and inscribed religious symbols on the billboard. He was asked to remove the symbols. When he did not oblige,he was threatened and his shop vandalised. Although Dharmu has had to give up his profession and does not have a steady income, he says he has found his “lost confidence and self-respect” in India. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His three children go to school and his eldest daughter, Meena, recently passed her Class VI exams at a government school, something which was not possible in the neighbouring country, he says. Dharmu’s story was echoed by other colony dwellers. They say they lived in fear in Pakistan, faced threats, victimisation and financial exclusion. When the first set of families settled in Delhi, word spread that “India was welcoming its people” and more started trickling in. | ||

| + | And yet every family has relatives left behind in Pakistan — a brother, son, daughter — and they fear for their safety, especially after India’s strikes against terrorist camps in Balakot, Pakistan. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ashutosh Joshi, an activist who runs crowdfunding campaigns to sponsor the colony’s every day expenses on medicines, diesel generator and house repairs, is also active in social media groups where people from Sindh share their “woes”. Citing the example of two Hindu girls, Raveena, 13, and Reena, 15, who were allegedly kidnapped by a group of “influential" men from their home in Ghotki in Sindh on the eve of Holi, Joshi claims that at least seven Hindu minor girls have been kidnapped in the past 35 days as “revenge” against the Balakot strike. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Nobody wants to leave their homes willingly. We were forced to leave Pakistan because we had no option. If someone assures us of safety, we will go back. But for now, India is our country.” | ||

| + | 60-year-old Meghi, who left Pakistan’s Hyderabad district four years ago | ||

| + | |||

| + | Joshi, a senior finance manager at a Noida-based multinational corporation, got involved in the colony’s activities two years ago and started a crowdfunding campaign on online platform, Milaap, raising Rs 15 lakh for the refugees’ rehabilitation. A portion went into sponsoring nine weddings in January. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Most brides and grooms were from within the community, but some were refugees from another colony in Majnu ka Tila,” says Joshi, who started another online campaign on Milaap recently. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The refugee colony in Majnu ka Tila, a few kilometres away, was set up in 2011. Today, there are over 500 people from seven districts of Sindh living here. There are seven pradhans (chiefs) who oversee the colony’s everyday affairs. Dharamveer, one of the pradhans, came to India in 2014. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He says he migrated because he couldn’t practise his religion in Pakistan. “Our children could not study. Even when they did, the education was theocratic,” he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The struggle here is about an electricity connection. There was some respite in 2015, when the Arvind Kejriwal government facilitated regular water supply to the colony and a 24-hour generator. The power line was, however, discontinued in 2017, plunging the colony back in darkness. Since then, the pradhans have written regularly to authorities to reinstall their power supply but they have not got any reply. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our children could not study in Pakistan. Even when they did, the education was theocratic | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The Yamuna is just a few metres from our dwellings. Snakes are found here regularly and without light, it is difficult to protect ourselves in the darkness,” says Dharamveer. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But, he does not regret moving to India. “Here, our problems are limited to food and water. In Pakistan, we had to be on constant vigil to ensure the safety of our women,” he says. “All of us know someone who has been forcibly converted. At most times, they don’t ask us to convert but constantly preach their own religion.” He adds that he came to Delhi on a visitor’s visa after telling officials in Pakistan that he was travelling for the Kumbh Mela in Uttar Pradesh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite all difficulties, the decision to leave their ancestral homes wasn’t easy. As 60-year-old Meghi, who left Pakistan’s Hyderabad district four years ago, says, “Nobody wants to leave their homes willingly. We were forced to leave Pakistan because we had no option. If someone assures us of safety, we will go back. But for now, India is our country.” | ||

=In Delhi= | =In Delhi= | ||

Latest revision as of 08:45, 7 April 2019

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Why Hindus leave Pakistan for India

[edit] As in 2019

Anam Ajmal, April 4, 2019: The Times of India

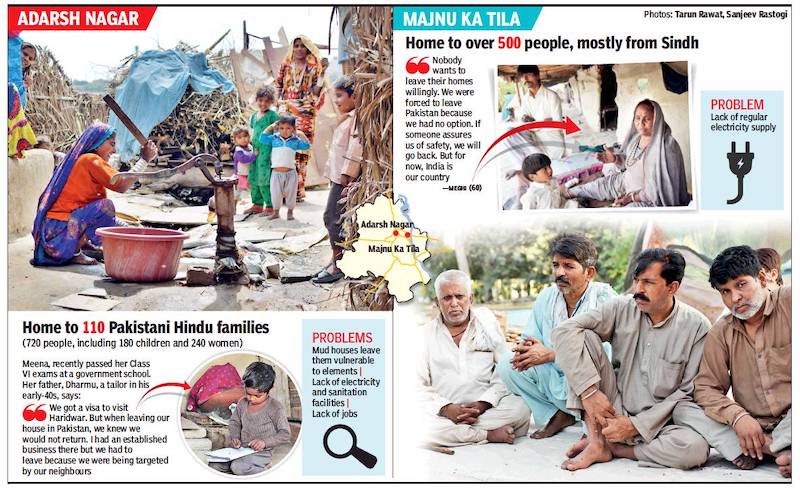

The refugees live in makeshift houses and tents in Delhi. Despite the lack of infrastructure, they say they have found ‘freedom” here. The decision to leave their home was not easy but they were left with no option

Almost every family living in the two refugee colonies in the capital for Hindus from Pakistan has a story to tell on what impelled them to leave their homes and flee to India.

Dharmu ‘Master’, a tailor in his early-40s, came to India in 2017. His wife and three children took the only train — Thar Express — from his village in Sindh and got down at Jodhpur in Rajasthan before coming to Delhi. “We got a visa to visit Haridwar. But while leaving our house in Pakistan, we knew we would not return again,” says Dharmu. “I had an established business there but we had to leave because we were being targeted by our neighbours.”

Trouble started in 2016 when Dharmu opened a new shop and inscribed religious symbols on the billboard. He was asked to remove the symbols. When he did not oblige,he was threatened and his shop vandalised. Although Dharmu has had to give up his profession and does not have a steady income, he says he has found his “lost confidence and self-respect” in India.

His three children go to school and his eldest daughter, Meena, recently passed her Class VI exams at a government school, something which was not possible in the neighbouring country, he says. Dharmu’s story was echoed by other colony dwellers. They say they lived in fear in Pakistan, faced threats, victimisation and financial exclusion. When the first set of families settled in Delhi, word spread that “India was welcoming its people” and more started trickling in. And yet every family has relatives left behind in Pakistan — a brother, son, daughter — and they fear for their safety, especially after India’s strikes against terrorist camps in Balakot, Pakistan.

Ashutosh Joshi, an activist who runs crowdfunding campaigns to sponsor the colony’s every day expenses on medicines, diesel generator and house repairs, is also active in social media groups where people from Sindh share their “woes”. Citing the example of two Hindu girls, Raveena, 13, and Reena, 15, who were allegedly kidnapped by a group of “influential" men from their home in Ghotki in Sindh on the eve of Holi, Joshi claims that at least seven Hindu minor girls have been kidnapped in the past 35 days as “revenge” against the Balakot strike.

“Nobody wants to leave their homes willingly. We were forced to leave Pakistan because we had no option. If someone assures us of safety, we will go back. But for now, India is our country.” 60-year-old Meghi, who left Pakistan’s Hyderabad district four years ago

Joshi, a senior finance manager at a Noida-based multinational corporation, got involved in the colony’s activities two years ago and started a crowdfunding campaign on online platform, Milaap, raising Rs 15 lakh for the refugees’ rehabilitation. A portion went into sponsoring nine weddings in January.

“Most brides and grooms were from within the community, but some were refugees from another colony in Majnu ka Tila,” says Joshi, who started another online campaign on Milaap recently.

The refugee colony in Majnu ka Tila, a few kilometres away, was set up in 2011. Today, there are over 500 people from seven districts of Sindh living here. There are seven pradhans (chiefs) who oversee the colony’s everyday affairs. Dharamveer, one of the pradhans, came to India in 2014.

He says he migrated because he couldn’t practise his religion in Pakistan. “Our children could not study. Even when they did, the education was theocratic,” he says.

The struggle here is about an electricity connection. There was some respite in 2015, when the Arvind Kejriwal government facilitated regular water supply to the colony and a 24-hour generator. The power line was, however, discontinued in 2017, plunging the colony back in darkness. Since then, the pradhans have written regularly to authorities to reinstall their power supply but they have not got any reply.

Our children could not study in Pakistan. Even when they did, the education was theocratic

“The Yamuna is just a few metres from our dwellings. Snakes are found here regularly and without light, it is difficult to protect ourselves in the darkness,” says Dharamveer.

But, he does not regret moving to India. “Here, our problems are limited to food and water. In Pakistan, we had to be on constant vigil to ensure the safety of our women,” he says. “All of us know someone who has been forcibly converted. At most times, they don’t ask us to convert but constantly preach their own religion.” He adds that he came to Delhi on a visitor’s visa after telling officials in Pakistan that he was travelling for the Kumbh Mela in Uttar Pradesh.

Despite all difficulties, the decision to leave their ancestral homes wasn’t easy. As 60-year-old Meghi, who left Pakistan’s Hyderabad district four years ago, says, “Nobody wants to leave their homes willingly. We were forced to leave Pakistan because we had no option. If someone assures us of safety, we will go back. But for now, India is our country.”

[edit] In Delhi

[edit] As in 2019

From: Anam Ajmal, For Pak Hindus, home is where the mind is without fear, March 29, 2019: The Times of India

Almost every family living in the two refugee colonies in the capital for Hindus from Pakistan has a story to tell on what impelled them to leave their homes and flee to India.

Dharmu ‘Master’, a tailor in his early-40s, came to India in 2017. His wife and three children took the only train — Thar Express — from his village in Sindh and got down at Jodhpur in Rajasthan before coming to Delhi. “We got a visa to visit Haridwar. But while leaving our house in Pakistan, we knew we would not return again,” says Dharmu. “I had an established business there but we had to leave because we were being targeted by our neighbours.”

Trouble started in 2016 when Dharmu opened a new shop and inscribed religious symbols on the billboard. He was asked to remove the symbols. When he did not oblige, he was threatened and his shop vandalised. Although Dharmu has had to give up his profession and does not have a steady income, he says he has found his “lost confidence and self-respect” in India.

His three children go to school and his eldest daughter, Meena, recently passed her Class VI exams at a government school, something which was not possible in the neighbouring country, he says.

Dharmu’s story was echoed by other colony dwellers. They say they lived in fear in Pakistan, faced threats, victimisation and financial exclusion. When the first set of families settled in Delhi, word spread that “India was welcoming its people” and more started trickling in.

And yet every family has relatives left behind in Pakistan — a brother, son, daughter — and they fear for their safety, especially after India’s strikes against terrorist camps in Balakot, Pakistan.

Ashutosh Joshi, an activist who runs crowdfunding campaigns to sponsor the colony’s every day expenses on medicines, diesel generator and house repairs, is also active in social media groups where people from Sindh share their “woes”. Citing the example of two Hindu girls, Raveena, 13, and Reena, 15, who were allegedly kidnapped by a group of “influential” men from their home in Ghotki in Sindh on the eve of Holi, Joshi claims that at least seven Hindu minor girls have been kidnapped in the past 35 days as “revenge” against the Balakot strike.

Joshi, a senior finance manager at a Noida-based multinational corporation, got involved in the colony’s activities two years ago and started a crowdfunding campaign on online platform, Milaap, raising Rs 15 lakh for the refugees’ rehabilitation. A portion went into sponsoring nine weddings in January.

“Most brides and grooms were from within the community, but some were refugees from another colony in Majnu ka Tila,” says Joshi, who started another online campaign on Milaap recently.

The refugee colony in Majnu ka Tila, a few kilometres away, was set up in 2011. Today, there are over 500 people from seven districts of Sindh living here. There are seven pradhans (chiefs) who oversee the colony’s everyday affairs. Dharamveer, one of the pradhans, came to India in 2014. He says he migrated because he couldn’t practise his religion in Pakistan. “Our children could not study. Even when they did, the education was theocratic,” he says.

The struggle here is about an electricity connection. There was some respite in 2015, when the Arvind Kejriwal government facilitated regular water supply to the colony and a 24-hour generator. The power line was, however, discontinued in 2017, plunging the colony back in darkness. Since then, the pradhans have written regularly to authorities to reinstall their power supply but they have not got any reply.

“The Yamuna is just a few metres from our dwellings. Snakes are found here regularly and without light, it is difficult to protect ourselves in the darkness,” says Dharamveer.

But, he does not regret moving to India. “Here, our problems are limited to food and water. In Pakistan, we had to be on constant vigil to ensure the safety of our women,” he says. “All of us know someone who has been forcibly converted. At most times, they don’t ask us to convert but constantly preach their own religion.”

He adds that he came to Delhi on a visitor’s visa after telling officials in Pakistan that he was travelling for the Kumbh Mela in Uttar Pradesh.

Despite all difficulties, the decision to leave their ancestral homes wasn’t easy. As 60-year-old Meghi, who left Pakistan’s Hyderabad district four years ago, says, “Nobody wants to leave their homes willingly. We were forced to leave Pakistan because we had no option. If someone assures us of safety, we will go back. But for now, India is our country.”