Indian Army: History (1761- )

(→Nawab Shuja ud-Daulah of Avadh) |

(→Pay and perquisites during British Raj) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one user not shown) | |||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

The pensions varied across ranks and number of years spent in service and was , in the range of 50%-70% of sal aries (until 1973, officers were paid 50% and sepoys, 70% of f their salary as pension. Today , it is 50% across ranks.) While the salaries and perks were good, the men were treated, says Dr Singh quoting Kipling, as `half-devil and half child' -in need of a nurturing hand and back-of-the-hand discipline. “Flogging re, mained a summary puni, shment until 1921, about 60 years after it disappeared from the British Army,“ he says. When India became inde pendent, Raj-era privileges were systematically taken , away from the armed forces. | The pensions varied across ranks and number of years spent in service and was , in the range of 50%-70% of sal aries (until 1973, officers were paid 50% and sepoys, 70% of f their salary as pension. Today , it is 50% across ranks.) While the salaries and perks were good, the men were treated, says Dr Singh quoting Kipling, as `half-devil and half child' -in need of a nurturing hand and back-of-the-hand discipline. “Flogging re, mained a summary puni, shment until 1921, about 60 years after it disappeared from the British Army,“ he says. When India became inde pendent, Raj-era privileges were systematically taken , away from the armed forces. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Regiments, class- based= | ||

| + | [https://indianexpress.com/article/research/why-class-based-regiments-have-survived-test-of-time-in-indian-army-8046647/ Adrija Roychowdhury, July 25, 2022: ''The Indian Express''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | On September 12, 1946, soon after taking oath as the minister of external affairs in India’s pre-Independence cabinet, Jawaharlal Nehru sent a letter to the commander-in-chief and defence secretary urging large-scale reforms in the Indian Army. In Nehru’s opinion, these reforms were necessary to safeguard the democracy that was about to be born. The need of the hour, argued Nehru, was to “transform the whole background of the Indian Army” and change its composition based on the martial classes recruited heavily from Punjab and a few other areas. Instead, the army needed to be opened up in ways that reflected the aspirations of the larger Indian nation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the years that followed, although some mixed class regiments were formed, the infantry remained largely caste and community based. As of now, there are 26 class based regiments in the Indian Army. The recently announced Agnipath scheme of the Indian government is expected to transform the class based recruitment of the army and open them up on an “all India, all class” basis. Although the nature and extent of the reform are yet to be decided, if it goes through it would be a historic moment for the army. While on one hand, caste and community based recruitments are seen to be divisive in nature, experts and senior officials in the army note the historic context in which the system arose and say that altering it might affect the feeling of brotherhood that is necessary for the military to perform well in war. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Colonial policy ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | When the British first came to India, they realised they did not have adequate white manpower for consolidating their rule in a foreign land. This was because of two reasons. First, European forces would be more costly and second, the Indian climate was too harsh for the white soldiers and most of them would want to leave too soon. Recruiting Indians in that sense was preferable since they were more acclimated to the geographical and social landscape and were more easily available. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Why were Indians willing to fight in the British Army is a question that scholars have been trying to understand for years now. Military historian Kaushik Roy in his article, The construction of regiments in the Indian army: 1859-1913 (2001), suggests that it was “managerial expertise that was the chief factor in enabling the British to structure a combat-effective and loyal army from the subcontinent’s manpower.” The regimental structure of the army, which was a product of the military revolution in the West, was key to the success of the British in incorporating Indian soldiers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since nationalism could not be utilised in the construction of regimental pride, the British officers motivated the sepoys of the Bengal Army before 1857 by pandering to notions of caste. The Brahmins and Rajputs were particularly preferred and to please them, the lower castes were not enlisted. Roy in his work writes that by 1852, 70 per cent of the Bengal Army consisted of Purbiyas or the high castes of north India. Things changed, however, after the rebellion of 1857 in which the Purbiya units of the Bengal Army played a major role. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the latter half of the 19th century studies on eugenics had taken off in Europe. British officers in India realised that race and not caste must be the basis on which characteristics of communities ought to be determined. Thereafter, the Martial Race theory is what shaped recruitment policy in the Indian Army. It was premised on the fact that only select communities within the subcontinent, due to their biological and cultural superiority, were capable of bearing arms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lord Roberts, who was the commander-in-chief of the Indian Army between 1885 and 1893 argued that the fighting races of India were the Sikhs, Dogras, Gurkhas, Rajputs and Pathans. “The wheat-eating small peasants and communities inhabiting the cold frontier regions were considered martial,” writes Roy in a 2013 article in the peer-reviewed journal Modern Asian Studies. The Gurkhas and Sikhs had also fought the British in the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814 and the Anglo-Sikh wars and so the British were aware of their military strength and were interested in recruiting them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an interview with indianexpress.com, Roy explained that even though this policy of recruitment rested on the European theory of Martial Races, it also had indigenous roots. “For instance, in the Mughal army there were never any Bengalis or people from Madras. There was a tradition of soldiering being confined to certain groups and that tradition was further strengthened under British rule,” he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The British also wanted to make it much harder for troops within each Indian regiment to coordinate against them as they had done in 1857,” writes political scientist Steven Wilkinson in his book Army and Nation: The Military and Indian Democracy since Independence (2015). “The central idea here, again, was expressed by Sir Charles Wood, the Secretary of State for India, in a letter in May 1862: ‘If one regiment mutinies, I should like to have the next so alien that it would fire into it’.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is important to note that in the British understanding, class regiments did not consist of a single caste category, but a combination of different caste groups. For instance, the Dogras consisted of several different castes from Jammu, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh, Gorkhas included a number of different groups from East and West Nepal, and Kumaonis referred to multiple hill castes in the Uttarakhand region. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Roy in his book notes the British policy of shaping the identities of the Gorkhas, Rajputs and Sikhs — the three groups with the largest presence in the Indian Army after 1859. In case of the Rajput regiments, for instance, the British encouraged the practise of Hinduism against all other forms of local and tribal religious practises such as serpent worship. “The Rajputs were reminded, that even in the darkest hour, they fought bravely against the Muslim invaders of North India,” he writes. Similarly, Sikhism was strengthened among the Sikh regiments on the grounds that it was a religion based on martial ethos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Further, different regiments were allowed and encouraged to possess different uniforms to maintain a distinct identity and heighten each unit’s prestige. The 1st Punjab Cavalry, for instance, had a dark blue uniform with blue and scarlet pagris (turban). Their badges had ‘Delhi’ and ‘Lucknow’ inscribed on them as a reminder of their loyal behaviour during the revolt of 1857. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' An Army for an Independent India ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The reliance of the army on just a few regions and communities first emerged as a matter of concern during the First World War when there was increased demand for troops. Even though the British decided to recruit more broadly during this period, those employed from non-martial areas were involved mostly in support roles rather than as frontline combatants. Once the war ended in 1918, the regiments recruited from outside the favoured groups — such as the Bengal detachment that had served in Mesopotamia — were quickly dissolved on grounds that they had not performed well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But as Independence came closer, the highly imbalanced nature of the colonial army was increasingly understood as unsuitable for a democratic country. The most common argument was the unfairness of a system in which several communities and regions had to pay taxes for the upkeep of an army from which they were excluded. There was also the fear that if the army was dependent on just a few communities then those groups would have a larger say in national politics. “Finally, there was also the worry that army recruitment policies were preventing the development of a broader national identity that could transcend caste, class, region and religion,” writes Wilkinson. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Between 1935 and 1938 three motions were passed in the Council of State requesting a total reform in the martial race recruitment policy, all of which were rejected. They failed mainly because of the resistance of the British who realised that their control over India rested upon an army drawn from groups that had been ‘loyal’ to them in the past. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Things changed after 1947 when a large number of British regiments in the Indian Army left and most of the Muslim regiments were transferred to Pakistan, which meant that substantial adjustments had to be made. However, while the political instability within India and its territorial disputes with neighbouring regions was a big hurdle in reforming the system, the restructuring of the army was made all the more difficult because for most politicians including Nehru, the immediate aim after Independence was to cut down expenditure on the army. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The biggest opposition to reform though, came from the senior officers of the army, especially at a time when there was a possibility of India going to war with Pakistan soon. The first commander-in-chief General K M Cariappa’s views are a good representation of the senior leadership’s commitment towards the class regimental system. “Far from opposing the class regiment policy, as a Brigadier and the only Indian officer to serve on the 1944-45 Indian Army Reorganisation Committee, he pressed instead for the conversion of the five proposed post-1945 mixed regiments to single-class regiments in order to increase their military effectiveness,” writes Wilkinson. Cariappa’s support for single-class regiments was based on “factors of inter-class feeling and of reinforcement difficulties during war.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Similar views were shared by other senior officers as well. General K S Thimayya, who was the Chief of Army Staff between 1957 to 1961 is known to have suggested that “soldiers perform better when their units are not mixed…This has been proved. Also, the officers of a ‘pure’ battalion are apt to be more careful about expending their men, and this always improves morale.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wilkinson explains that it is not as if these officers adopted all aspects of the martial class prejudices of the British. “Cariappa for instance, had opposed the senior British officers’ denigration of some ‘non-martial’ groups’ military qualities when on the army reorganisation committee in 1944-45,” he writes. “But these officers did share the view that long regimental traditions and the attachment of particular groups to the regiment paid dividends in terms of fighting effectiveness.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Debates around the fixed class composition of regiments have come up on several occasions in the years following Independence. “This issue was raised in the Parliament in 2000 and 2016. In 2016, the Defence Minister Manohar Parikkar had said that the existing regiments of the Indian Army are constituted on the basis of enhancing cohesion and warfighting potential and have stood the test of time in an exemplary manner. Hence there is no requirement to break the cohesion of battalions or raise additional class based regiments,” says former Northern Army Commander, Lieutenant General B S Jaswal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the 1980s an experiment was carried out to mix battalions of fixed class regiments. “For instance, from the JAK RIF to which I belonged, troops were sent to the Assam Regiment and we got companies from the Marathas and the Garhwals,” narrates Jaswal, adding that the experiment failed miserably and the battalions were reverted immediately afterwards. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The reason for the failure of the experiment, explains Jaswal, was that they did not have the kind of cohesion that is required for frontline duties. “The Assam regiment, for instance, has a completely different food and language culture from that of a regiment consisting of Punjabis,” he says. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lt General J S Cheema, as Deputy Chief of Army Staff from the Sikh regiment explains that the bulk of the Indian army comprises of men from the villages. “For them the affinity that is a product of being from the same region or having the same language, religion and culture becomes a strong motivating factor.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The sense of camaraderie of brotherhood formed in the battalions is known to play a big role in looking out for each other when in combat. Jaswal recalls an incident that took place during the 1965 Indo-Pak war. “There were these two soldiers from a village in Himachal who virtually ate from the same plate. In the course of the war, one of them was hit and left behind in a brook. The other one ran back from where he was to pick him up and bring him back immediately,” he narrates. “The reason was it would be impossible for him to face his village kinsmen if he left behind his friend. He would be ostracised.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | A similar example of bonhomie is cited from the Battle of Rezang La during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In this historic battle, the Ahirs from Haryana fighting in the 13 Kumaon Regiment are known to have valiantly fought back repeated attacks from the Chinese. “They were practically all from the same village, related to each other. Brothers, fathers and sons, fought together in the same trench,” says Jaswal. He adds, “Courage increases exponentially when those fighting belong to the same region.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Defence|AINDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- ) | ||

| + | INDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- )]] | ||

| + | [[Category:History|AINDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- ) | ||

| + | INDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- )]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|AINDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- ) | ||

| + | INDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- )]] | ||

| + | |||

=A mercenary tradition converted into a nationalist tradition in August, 1947= | =A mercenary tradition converted into a nationalist tradition in August, 1947= | ||

[http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=AAKARVANI-Nothing-can-be-said-about-our-faujis-06112016022050 AAKAR PATEL, Nothing can be said about our faujis, they're above criticism, Nov 06 2016 : The Times of India] | [http://epaperbeta.timesofindia.com/Article.aspx?eid=31808&articlexml=AAKARVANI-Nothing-can-be-said-about-our-faujis-06112016022050 AAKAR PATEL, Nothing can be said about our faujis, they're above criticism, Nov 06 2016 : The Times of India] | ||

| Line 119: | Line 184: | ||

=See also= | =See also= | ||

| + | [[Indian Army: History (1761- )]] | ||

| + | |||

[[Indian Army: History (1947- )]] | [[Indian Army: History (1947- )]] | ||

| Line 125: | Line 192: | ||

[[World War II and India]] | [[World War II and India]] | ||

| − | and many more... | + | [[World War 1: The Dogras]] |

| + | |||

| + | and many more by clicking the '''Defence''' button below... | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Defence|A | ||

| + | INDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- )]] | ||

| + | [[Category:History|A | ||

| + | INDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- )]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|A | ||

| + | INDIAN ARMY: HISTORY (1761- )]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:55, 1 August 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Part 1: Panipat to Festubert

Evolution of Indian military: From Panipat to Festubert

The Times of India Manimugdha S Sharma,TNN | Sep 26, 2014

[edit] 1761: Panipat

Late afternoon on January 14, 1761, Maratha generals and soldiers fleeing the battlefield at Panipat took with them an indelible memory of Ibrahim Khan Gardi's artillery and musketeers wreaking havoc on the enemy "like a knife slicing through butter". Despite their thinning ranks, the French-trained Telangi infantry, who called themselves Gardis in the honour of their illustrious commander, fought like true professionals. Though predominantly Muslim, they stayed loyal to the Brahmin Peshwa and fought a Muslim coalition, ignoring blandishments and threats till the very end. If all Maratha generals had stuck to the original plan drawn up by Ibrahim Khan-that of forming a hollow infantry square and forcing a passage to Delhi by destroying the Afghan right flank-the result of the Third Battle of Panipat could have been different.

But despite the defeat, Panipat made it clear to the Indians that subsequent battles in the subcontinent will be won by the boom of artillery and rattle of musketry. According to Dr Uday S Kulkarni's exhaustive account of the battle titled 'Solstice At Panipat: 14 January 1761', Maratha generals like Scindia, Holkar and Gaekwad, who were staunch critics of Maratha commander-in-chief Sadashivrao Bhau's touching faith in Ibrahim Khan Gardi and his European style of fighting, would change their minds and increasingly repose faith in European-styled drilled infantry and artillery. In fact, they would also abandon their traditional strength of guerrilla warfare or ganimi kava, a process that started right from the Panipat battlefield. But the Marathas weren't alone in this: soon, most Indian rulers were racing one another to modernise their armies. This phase also saw a gradual departure from the mediaeval practice of assigning more weightage to cavalry than any other combat arm.

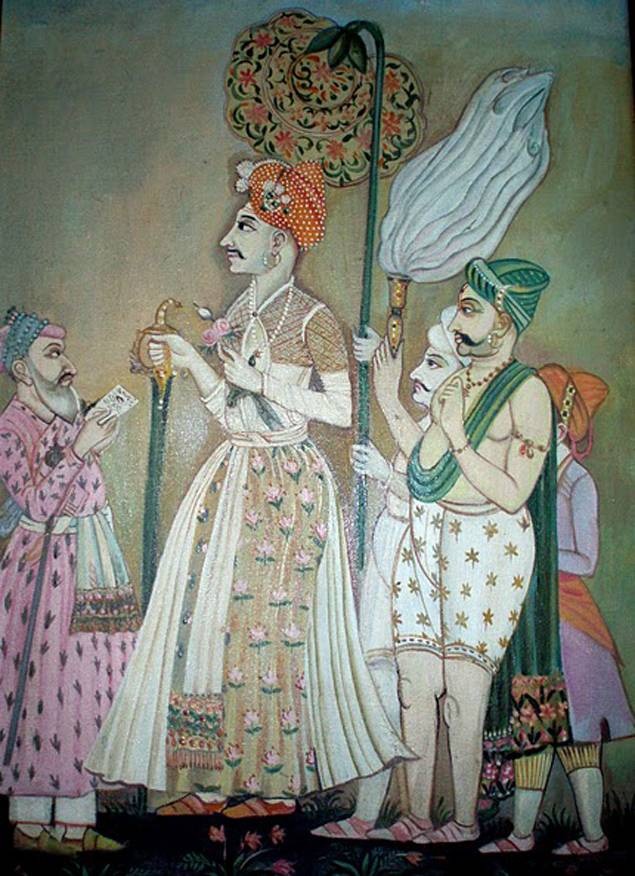

[edit] Nawab Shuja ud-Daulah of Avadh

But it was Nawab Shuja ud-Daulah of Avadh who was among the first to utilise lessons learnt at Panipat. He had allied himself with Ahmed Shah Abdali, but neither he nor his forces took any active part in the battle. In 1764, his moderately Europeanised army led by westerners-including Walter Reinhardt Sombre or 'Samru sahib', the husband of Begum Samru-gave a tough time to the English at Buxar, the first battle fought by the English for territorial control in India. Shuja's army also had Rohillas and Afghan cavalry, who were mostly veterans of Panipat. His artillery directed devastating fire on the British. But the British held out with the wily Hector Munro in command and some disciplined musketry by the infantry, the backbone of which was formed by over 5,000 sepoys. Shuja's forces, with all their bravery, had no answer for the Anglo-Indian bayonet charge.

Despite the defeat, Shuja continued to modernise his army, raising 18 European-styled infantry battalions by the 1770s. But he would never get the chance to measure swords with the English again as Avadh became a vassal state of the English after Buxar.

[edit] Buxar

Indian history books today, while recognising Buxar as a watershed moment in our national history, skip another important point: that it was at Buxar that the identity of the Indian sepoy as a match-winner for the British was established (though four years earlier at Plassey, Robert Clive was disappointed with Indian officers and made it a rule that Indian troops will only be officered by Europeans-a condition that stuck on until the end of First World War). And it was at Buxar that the foundation of the Indian Army of today was laid. From that point on, the sepoy would be the backbone of English armies conquering different Indian states one by one. The English would gradually develop a blind faith in the Indian sepoy: a phase that would last until 1857 and continue again towards the end of the 19th century.

For the Marathas, it was Mahadji Scindia who broke new ground in Europeanisation of his army. Scindia employed a brilliant French mercenary, Benoit de Boigne, to raise a brigade that could dress, march and fight as a European army. A former officer in the French, Russian and Honourable East India Company's armies, de Boigne taught Scindia's men the British musket drill and everything else that he knew on the condition that he wouldn't be made to fight the English with whom he had cordial relations. Mahadji's meteoric rise as the dominant power in the north of India hinged on the shoulders of this able Frenchman. Mahadji's new, formidable army came to be known as 'Fauj-i-Hind' or 'Army of Hindustan'. By 1790, it had 37,000 soldiers trained in the European fashion, and 330 pieces of artillery. But after Mahadji's death in 1794, his less capable grandnephew and successor Daulat Rao Scindia would fritter away the gains of his predecessor. He would wage fratricidal wars with other Maratha chieftains and lose both territory and reputation fighting the British. His army stopped attracting talent, both due to his own apathy and some shameless nepotism practised by his French general, Perron. But they would still give Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, his "toughest battle" at Assaye.

[edit] Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan

Elsewhere in the south, Nawab Hyder Ali was raising a formidable army. Hyder was impressed with the British and wanted their military assistance to modernise his army. The British were reluctant, which led Hyder to seek help from the French. With French help, Hyder modernised his infantry and artillery, but unlike other Indian powers of the day that ignored cavalry, Hyder's focus was always on his cavalry and he used it with great skill, always leading it from the front. In fact, the Mysore cavalry, with its dash and daring, had built for itself a fearsome reputation among its rivals. In the 1770s, Hyder Ali had 20,000 cavalry, 20 battalions of infantry and an unknown quantity of guns. Even the English grudgingly admitted Mysore cavalry's superiority, though they referred to its actions as that of a swarm of locusts on crops.

Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan also abandoned the common Indian practice of engaging militias raised by provincial governors in war time and went for a fully centralised recruiting and training system. A very rudimentary form of regimental system was also followed. But by Tipu Sultan's time, Mysore artillery had attained a high degree of finesse. Tipu introduced a rocket artillery corps organised in kushoons. Tipu's guns were also known for their longer range and accuracy. It's not known how many artillery pieces he had; but at the fall of Srirangapatnam and Tipu's death in 1799, the British found 421 gun carriages, 176 12 pounders and 4,12,000 iron round shots ranging from four to 42 pounds inside the fort.

A few years after Tipu Sultan's collapse, the process of the end of the Maratha Empire began as well. The Peshwa signed the Treaty of Bassein with the English in 1802, agreeing to station a 6,000-strong British force in his territory. The Poona Horse (now 17 Horse, Indian Army) was thus born.

[edit] Third Anglo-Maratha War

After the Third Anglo-Maratha War ended in 1818, the Maratha Empire ceased to exist and the Peshwa's army was disbanded. Many former soldiers of the Peshwa found service in the Bombay Army of the HEIC. They were placed in the Poona Horse, Bombay Sappers and Miners and Maratha Light Infantry. Among the first to join these regiments were the Gardis.

Up north, with the decline of the Scindia's power and due to irregularities in pay, many of Scindia's well-trained troops left him and sought greener pastures to the west. They soon found a new employer who was willing to pay them more, both respect and money.

[edit] Maharaja Ranjit Singh

He was Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the lion of Punjab.

Ranjit Singh wanted to modernise his army. The visionary ruler knew a clash with the British was inevitable at some point in the future and he wanted to be fully prepared for that. He employed Europeans of different nationalities to train his troops. Ranjit Singh organised his infantry on French lines, cavalry on British as well as traditional lines, and artillery on European lines. The English were so alarmed by this tremendous expansion of force that they ordered the arrest of any Frenchman trying to cross the Sutlej.

Despite the build-up, the clash that Ranjit Singh foresaw didn't happen in his lifetime but after his death and when the Sikh state was in considerable decay.

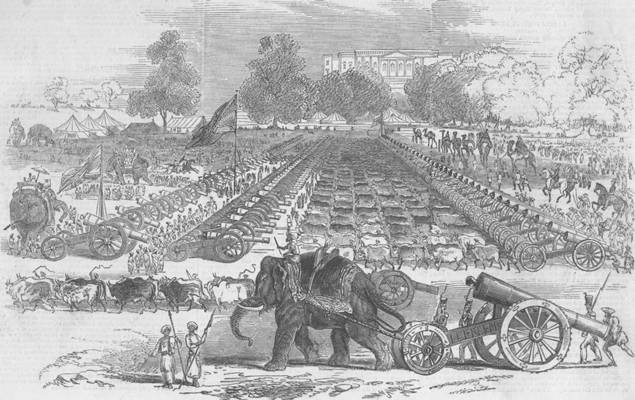

Just before the First Anglo-Sikh War, the Sikh army had grown bigger than the state could support. According to UK-based military historian Amarpal Singh's book, 'The First Anglo-Sikh War', in 1839, the Lahore state had an army consisting just under 47,000 regular infantry,16,000 regular and irregular cavalry, and 500 pieces of artillery. The artillery was mostly manned by Muslim gunners.

But after Ranjit Singh's death, there was a period of anarchy that saw too many court intrigues and rapid decline in leadership of the army. The army, though, continued to expand (over 80,000 in 1845) and went out of control. It functioned through village panchayats that were subservient to none. The soldiers were paid twice the sum that a sepoy in HEIC's army received every month. The soldiers also resorted to loot and plunder whenever they wanted.

Amarpal Singh argues that the Lahore state engineered a situation whereby the growing influence of this republican Sikh army could be curbed-by crossing the Sutlej and inviting an English attack in 1845.

All through the war, the Sikh commanders abandoned the field, leaving their men to fend for themselves, at early stages of battles. At Ferozeshah, for instance, the Sikhs had clearly dominated the battlefield with their artillery completely destroying the British artillery, and infantry returning fire with amazing rapidity. Sitaram, a sepoy in the British army, as quoted by Singh in his book, pretty much summed up the ground reality when he wrote: "Volleys of musketry were delivered by us at close quarters, and were returned just as steadily by the enemy. In all the previous actions in which I had taken part one or two volleys at short range were as much as the Sirkar's (the British state's) enemies could stand; but these Sikhs gave volley for volley, and never gave way until nearly decimated..."

Yet, instead of moving forward and decimating the enemy, the commander, Lal Singh, ordered a general retreat, much to the chagrin of his own troops. The Sikhs abandoned all their guns and equipment and left.

(To be continued)

(Write to this correspondent at manimugdha.sharma@timesgroup.com)

[edit] Pay and perquisites during British Raj

The Times of India, Jul 06 2015

Manimugdha Sharma

Were Army pay and perks better under the British?

At Delhi's Jantar Man tar, armed forces veter ans have been sitting on a relay hunger strike since June 15 to protest against the Modi government's flip-flops on the implementation of OROP (One Rank, One Pension) scheme. “Is this a government of our people? Even the British treated us better,“ a war veteran mutters.

So, did the Raj really treat Indian soldiers better? The Indian Army sepoy was never really paid well at any point in history . After the Mughals, the East India Company became the best paymaster in the subcontinent, and the prospect of regular pay attracted talent from all corners of the country . It was perhaps rivalled only by the Sikh Empire after Maharaja Ranjit Singh's death and that too for a short time (the Khalsa Army's pay was double the Company salaries).

“The Army got a better deal during the Raj. Western societies look up to the Army as an institution that upholds the nation state. It's still customary in the US for people to say `thank you' to a war veteran; in the UK, they make way for war heroes, and a Victoria Cross winner always meets with a standing ovation wherever he goes. In India, the colonial state accorded privileges to the Army because it was essential for British rule,“ says military historian Squadron Leader Rana Chhina (Retd) of USI-CAFHR. Dr Gajendra Singh, who teaches South Asian history at the University of Exeter, says the monthly pay of a sepoy was fixed at Rs 7 in 1860, Rs 9 in 1895 and Rs 11 in 1911. But the money was often lower than the cost of subsistence which was estimated in 1875 at Rs 7, two annas and five paise.

Indian officers in the 1860s and thereafter were, of course, better off. A risaldar major in the cavalry was paid Rs 150, a risaldar Rs 80, and a jemadar Rs 50 a month. But even these were extraordinarily low when compared to what the European officers received: cavalry or horse artillery colonels, for instance, were paid Rs 1,478 per month, lieutenant colonels, Rs 1,032 and majors, Rs 929. By today's standards, the colonel was being paid the equivalent of around Rs 8 lakh then (as per the National Archives, UK, old currency converter, Rs 1,478 is approximately 280 pounds per day , which is around Rs 8 lakh per month).

Worried that the Raj wouldn't attract top talent, se poy salaries were upped in the latter half of the 19th century .

About 40% of the Indian Ar my in peacetime was allowed to go on furlough to till their lands. “ Also, extraordinary payments like batta were fixed at an extra Rs 5 by 1914 and British officers were en couraged to shower gifts on their men. Military service by the 1890s in Punjab was seen as a way of getting a land grant upon discharge, of em ployment in other forms of co lonial service, or of enabling migration abroad -up to 50% of early Punjabi migrants to Canada and California in 1901-1911 were pensioned sol diers,“ Dr Singh says.

The pensions varied across ranks and number of years spent in service and was , in the range of 50%-70% of sal aries (until 1973, officers were paid 50% and sepoys, 70% of f their salary as pension. Today , it is 50% across ranks.) While the salaries and perks were good, the men were treated, says Dr Singh quoting Kipling, as `half-devil and half child' -in need of a nurturing hand and back-of-the-hand discipline. “Flogging re, mained a summary puni, shment until 1921, about 60 years after it disappeared from the British Army,“ he says. When India became inde pendent, Raj-era privileges were systematically taken , away from the armed forces.

[edit] Regiments, class- based

Adrija Roychowdhury, July 25, 2022: The Indian Express

On September 12, 1946, soon after taking oath as the minister of external affairs in India’s pre-Independence cabinet, Jawaharlal Nehru sent a letter to the commander-in-chief and defence secretary urging large-scale reforms in the Indian Army. In Nehru’s opinion, these reforms were necessary to safeguard the democracy that was about to be born. The need of the hour, argued Nehru, was to “transform the whole background of the Indian Army” and change its composition based on the martial classes recruited heavily from Punjab and a few other areas. Instead, the army needed to be opened up in ways that reflected the aspirations of the larger Indian nation.

In the years that followed, although some mixed class regiments were formed, the infantry remained largely caste and community based. As of now, there are 26 class based regiments in the Indian Army. The recently announced Agnipath scheme of the Indian government is expected to transform the class based recruitment of the army and open them up on an “all India, all class” basis. Although the nature and extent of the reform are yet to be decided, if it goes through it would be a historic moment for the army. While on one hand, caste and community based recruitments are seen to be divisive in nature, experts and senior officials in the army note the historic context in which the system arose and say that altering it might affect the feeling of brotherhood that is necessary for the military to perform well in war.

Colonial policy

When the British first came to India, they realised they did not have adequate white manpower for consolidating their rule in a foreign land. This was because of two reasons. First, European forces would be more costly and second, the Indian climate was too harsh for the white soldiers and most of them would want to leave too soon. Recruiting Indians in that sense was preferable since they were more acclimated to the geographical and social landscape and were more easily available.

Why were Indians willing to fight in the British Army is a question that scholars have been trying to understand for years now. Military historian Kaushik Roy in his article, The construction of regiments in the Indian army: 1859-1913 (2001), suggests that it was “managerial expertise that was the chief factor in enabling the British to structure a combat-effective and loyal army from the subcontinent’s manpower.” The regimental structure of the army, which was a product of the military revolution in the West, was key to the success of the British in incorporating Indian soldiers.

Since nationalism could not be utilised in the construction of regimental pride, the British officers motivated the sepoys of the Bengal Army before 1857 by pandering to notions of caste. The Brahmins and Rajputs were particularly preferred and to please them, the lower castes were not enlisted. Roy in his work writes that by 1852, 70 per cent of the Bengal Army consisted of Purbiyas or the high castes of north India. Things changed, however, after the rebellion of 1857 in which the Purbiya units of the Bengal Army played a major role.

By the latter half of the 19th century studies on eugenics had taken off in Europe. British officers in India realised that race and not caste must be the basis on which characteristics of communities ought to be determined. Thereafter, the Martial Race theory is what shaped recruitment policy in the Indian Army. It was premised on the fact that only select communities within the subcontinent, due to their biological and cultural superiority, were capable of bearing arms.

Lord Roberts, who was the commander-in-chief of the Indian Army between 1885 and 1893 argued that the fighting races of India were the Sikhs, Dogras, Gurkhas, Rajputs and Pathans. “The wheat-eating small peasants and communities inhabiting the cold frontier regions were considered martial,” writes Roy in a 2013 article in the peer-reviewed journal Modern Asian Studies. The Gurkhas and Sikhs had also fought the British in the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814 and the Anglo-Sikh wars and so the British were aware of their military strength and were interested in recruiting them.

In an interview with indianexpress.com, Roy explained that even though this policy of recruitment rested on the European theory of Martial Races, it also had indigenous roots. “For instance, in the Mughal army there were never any Bengalis or people from Madras. There was a tradition of soldiering being confined to certain groups and that tradition was further strengthened under British rule,” he says.

“The British also wanted to make it much harder for troops within each Indian regiment to coordinate against them as they had done in 1857,” writes political scientist Steven Wilkinson in his book Army and Nation: The Military and Indian Democracy since Independence (2015). “The central idea here, again, was expressed by Sir Charles Wood, the Secretary of State for India, in a letter in May 1862: ‘If one regiment mutinies, I should like to have the next so alien that it would fire into it’.”

It is important to note that in the British understanding, class regiments did not consist of a single caste category, but a combination of different caste groups. For instance, the Dogras consisted of several different castes from Jammu, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh, Gorkhas included a number of different groups from East and West Nepal, and Kumaonis referred to multiple hill castes in the Uttarakhand region.

Roy in his book notes the British policy of shaping the identities of the Gorkhas, Rajputs and Sikhs — the three groups with the largest presence in the Indian Army after 1859. In case of the Rajput regiments, for instance, the British encouraged the practise of Hinduism against all other forms of local and tribal religious practises such as serpent worship. “The Rajputs were reminded, that even in the darkest hour, they fought bravely against the Muslim invaders of North India,” he writes. Similarly, Sikhism was strengthened among the Sikh regiments on the grounds that it was a religion based on martial ethos.

Further, different regiments were allowed and encouraged to possess different uniforms to maintain a distinct identity and heighten each unit’s prestige. The 1st Punjab Cavalry, for instance, had a dark blue uniform with blue and scarlet pagris (turban). Their badges had ‘Delhi’ and ‘Lucknow’ inscribed on them as a reminder of their loyal behaviour during the revolt of 1857.

An Army for an Independent India

The reliance of the army on just a few regions and communities first emerged as a matter of concern during the First World War when there was increased demand for troops. Even though the British decided to recruit more broadly during this period, those employed from non-martial areas were involved mostly in support roles rather than as frontline combatants. Once the war ended in 1918, the regiments recruited from outside the favoured groups — such as the Bengal detachment that had served in Mesopotamia — were quickly dissolved on grounds that they had not performed well.

But as Independence came closer, the highly imbalanced nature of the colonial army was increasingly understood as unsuitable for a democratic country. The most common argument was the unfairness of a system in which several communities and regions had to pay taxes for the upkeep of an army from which they were excluded. There was also the fear that if the army was dependent on just a few communities then those groups would have a larger say in national politics. “Finally, there was also the worry that army recruitment policies were preventing the development of a broader national identity that could transcend caste, class, region and religion,” writes Wilkinson.

Between 1935 and 1938 three motions were passed in the Council of State requesting a total reform in the martial race recruitment policy, all of which were rejected. They failed mainly because of the resistance of the British who realised that their control over India rested upon an army drawn from groups that had been ‘loyal’ to them in the past.

Things changed after 1947 when a large number of British regiments in the Indian Army left and most of the Muslim regiments were transferred to Pakistan, which meant that substantial adjustments had to be made. However, while the political instability within India and its territorial disputes with neighbouring regions was a big hurdle in reforming the system, the restructuring of the army was made all the more difficult because for most politicians including Nehru, the immediate aim after Independence was to cut down expenditure on the army.

The biggest opposition to reform though, came from the senior officers of the army, especially at a time when there was a possibility of India going to war with Pakistan soon. The first commander-in-chief General K M Cariappa’s views are a good representation of the senior leadership’s commitment towards the class regimental system. “Far from opposing the class regiment policy, as a Brigadier and the only Indian officer to serve on the 1944-45 Indian Army Reorganisation Committee, he pressed instead for the conversion of the five proposed post-1945 mixed regiments to single-class regiments in order to increase their military effectiveness,” writes Wilkinson. Cariappa’s support for single-class regiments was based on “factors of inter-class feeling and of reinforcement difficulties during war.”

Similar views were shared by other senior officers as well. General K S Thimayya, who was the Chief of Army Staff between 1957 to 1961 is known to have suggested that “soldiers perform better when their units are not mixed…This has been proved. Also, the officers of a ‘pure’ battalion are apt to be more careful about expending their men, and this always improves morale.”

Wilkinson explains that it is not as if these officers adopted all aspects of the martial class prejudices of the British. “Cariappa for instance, had opposed the senior British officers’ denigration of some ‘non-martial’ groups’ military qualities when on the army reorganisation committee in 1944-45,” he writes. “But these officers did share the view that long regimental traditions and the attachment of particular groups to the regiment paid dividends in terms of fighting effectiveness.”

Debates around the fixed class composition of regiments have come up on several occasions in the years following Independence. “This issue was raised in the Parliament in 2000 and 2016. In 2016, the Defence Minister Manohar Parikkar had said that the existing regiments of the Indian Army are constituted on the basis of enhancing cohesion and warfighting potential and have stood the test of time in an exemplary manner. Hence there is no requirement to break the cohesion of battalions or raise additional class based regiments,” says former Northern Army Commander, Lieutenant General B S Jaswal.

In the 1980s an experiment was carried out to mix battalions of fixed class regiments. “For instance, from the JAK RIF to which I belonged, troops were sent to the Assam Regiment and we got companies from the Marathas and the Garhwals,” narrates Jaswal, adding that the experiment failed miserably and the battalions were reverted immediately afterwards.

The reason for the failure of the experiment, explains Jaswal, was that they did not have the kind of cohesion that is required for frontline duties. “The Assam regiment, for instance, has a completely different food and language culture from that of a regiment consisting of Punjabis,” he says.

Lt General J S Cheema, as Deputy Chief of Army Staff from the Sikh regiment explains that the bulk of the Indian army comprises of men from the villages. “For them the affinity that is a product of being from the same region or having the same language, religion and culture becomes a strong motivating factor.”

The sense of camaraderie of brotherhood formed in the battalions is known to play a big role in looking out for each other when in combat. Jaswal recalls an incident that took place during the 1965 Indo-Pak war. “There were these two soldiers from a village in Himachal who virtually ate from the same plate. In the course of the war, one of them was hit and left behind in a brook. The other one ran back from where he was to pick him up and bring him back immediately,” he narrates. “The reason was it would be impossible for him to face his village kinsmen if he left behind his friend. He would be ostracised.”

A similar example of bonhomie is cited from the Battle of Rezang La during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In this historic battle, the Ahirs from Haryana fighting in the 13 Kumaon Regiment are known to have valiantly fought back repeated attacks from the Chinese. “They were practically all from the same village, related to each other. Brothers, fathers and sons, fought together in the same trench,” says Jaswal. He adds, “Courage increases exponentially when those fighting belong to the same region.”

[edit] A mercenary tradition converted into a nationalist tradition in August, 1947

I am revealing no secret when I say that what had been a mercenary army on August 14, 1947 renamed itself a nationalist army the next morning. We have no history before that of a nationalist army, unlike, say, Turkey .

The mercenary tradition of the Indian armed forces goes back at least 2,500 years. The first Greek historian Herodotus describes Indians at the battle of Plataea in 479 BC hired by the Persian emperor Xerxes (the Indians acquitted themselves well, though the battle was lost to the Greek alliance).

Ghalib, who died in 1869, said famously: “Sau pusht se, hai pesha-e-aba sipahgari“ (for a hundred generations, our family profession has been soldiery).The world has long respected the Indian soldier's abilities. It is he who taught the European trench fighting in what they call their Great War.

Alexander the Great's fawning biographers, Arrian, Quintus Curtius Rufus and Plutarch, say only one action stained the conqueror's record. He concluded a treaty with a group of Indian mercenaries and then treacherously had them murdered after they disarmed. He did so because he respected and was threatened by their fighting ability .

Every day, on my way to work, I go past the headquarters of the Madras Sappers in Bengaluru. A tank in desert camouflage is at the gate, its cannon overlooking the pretty Ulsoor Lake. I'd like to row on it but civilians are forbidden. On the lake are little rock islands on the walls of which are painted the names of great Sappers victories, like Assaye Ganj.

Who was defeated at Assaye? The Marathas. Who were the Sappers fighting for? Arthur Wellesley, later to become Duke Wellington (of Waterloo fame).The Sappers HQ gate proudly announces the year the unit was formed: 1780, more than a century and a half before Independence. Who did the Sappers shoot and bayonet and mine and blow up all these years? Other Indians.

Colonel Dyer only gave the order in 1919 at Jallianwala Bagh. Aim was taken and triggers pulled by the Gurkha Rifles, and by the Punjabis of Baloch Regiment (the Baloch did not and do not have a tradition of soldiery).

This country sleeps because its soldiers are awake, in the words of the Prime Minister. Such sentiment is accepted unquestioningly . It is because of this sentiment that a nation that spends Rs 33,000 crore on the health of its citizens paid Rs 59,000 crore for 36 warplanes this year. There was some criticism of this government because it actually cut the health budget.

[edit] See also

Indian Army: History (1761- )

and many more by clicking the Defence button below...