Ganga (Ganges), river

(→2016-19: water quality worsens) |

(→2016-19: water quality worsens) |

||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

It said, “Analysis of water quality monitoring data of CPCB for these two stations located on main stem of Ganga in Varanasi for the month of January for period 2016-19 indicates that minimum value of DO varied between 6.7 to 7.6 mg/L and indicated healthy state of river.” | It said, “Analysis of water quality monitoring data of CPCB for these two stations located on main stem of Ganga in Varanasi for the month of January for period 2016-19 indicates that minimum value of DO varied between 6.7 to 7.6 mg/L and indicated healthy state of river.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Germs impervious to common medicines / 2019== | ||

| + | [https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/health/ganges-drug-resistant-bacteria.html Dec 23, 2019 ''The New York Times''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Deepak K. Prasad, left, collected a water sample, while Rishabh Shukla, right, checked the temperature of the Ganges at Byasi, India, in the Himalayas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | GANGOTRI, India — High in the Himalayas, it’s easy to see why the Ganges River is considered sacred. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Hindu legend, the Milky Way became this earthly body of water to wash away humanity’s sins. As it drains out of a glacier here, rock silt dyes the ice-cold torrent an opaque gray, but biologically, the river is pristine — free of bacteria. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, long before it flows past any big cities, hospitals, factories or farms, its purity degrades. It becomes filled with a virulent type of bacteria, resistant to common antibiotics. | ||

| + | The Ganges is living proof that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are almost everywhere. The river offers powerful insight into the prevalence and spread of drug-resistant infections, one of the world’s most pressing public health problems. Its waters provide clues to how these pathogens find their way into our ecosystem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Winding over 1,500 miles to the Bay of Bengal, Ma Ganga — “Mother Ganges”— eventually becomes one of the planet’s most polluted rivers, a mélange of urban sewage, animal waste, pesticides, fertilizers, industrial metals and rivulets of ashes from cremated bodies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But annual tests by scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology show that antibiotic-resistant bacteria appear while the river is still flowing through the narrow gorges of the Himalayan foothills, hundreds of miles before it encounters any of the usual suspects that would pollute its waters with resistant germs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The bacterial levels are “astronomically high,” said Shaikh Ziauddin Ahammad, a professor of biochemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology. The only possible source is humans, specifically the throngs of ritual bathers who come to wash away their sins and immerse themselves in the waters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''India’s resistance problem''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Beyond the Ganges, India has some of the highest antibiotic-resistance rates in the world, according to a 2017 report from the government’s Ministry of Science and Technology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tests showed that about 70 percent of four bacteria species commonly found in hospital patients were resistant to typical first-line antibiotics. Between 12 percent and 71 percent — depending on the species tested — were also resistant to carbapenems, a class of antibiotics once considered the last line of defense. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other studies confirm the danger. An article in Lancet Infectious Diseases found that about 57 percent of infections in India with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common bacterium, were carbapenem-resistant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But where exactly do these armies of drug-resistant germs come from? Are they already everywhere — in the soil beneath our feet, for example? Do they emerge in hospitals, where antibiotics are heavily used? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Are they bred in the intestines of livestock on factory farms? Do they arise in the fish, plants or plankton living in lakes downstream from pharmaceutical factories? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Or are the germs just sitting inside the patients themselves, waiting for their hosts to weaken enough for them to take over? | ||

| + | |||

| + | Research now being done in India and elsewhere suggests an answer to these questions: Yes, all of the above. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But how drug-resistant bacteria jump from one human to another outside of a hospital setting is the least-understood part of the process, and that is why the findings from the Ganges are so valuable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Origins of drug-resistant germs''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Antibiotic-resistance genes are not new. They are nearly as old as life itself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On a planet that is about 4.5 billion years old, bacteria appeared about 3.8 billion years ago. As they fed on one other — and later on molds, fungi, plants and animals — their victims evolved genes to make bacteria-killing proteins or toxins, nature’s antibiotics. (Penicillin, for example, was discovered growing in mold.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The bacteria, in turn, evolved defenses to negate those antibiotics. What modern medicine has done, scientists say, is put constant Darwinian pressure on bacteria. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Outside the body, they face sunlight, soap, heat, bleach, alcohol and iodine. Inside, they face multiple rounds of antibiotics. Only the ones that can evolve drug-resistance genes — or grab them from a nearby species, which some bacteria can do — will survive. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The result is a global bout of sudden-death elimination at a microscopic level. Bacteria once susceptible to all families of antibiotics have become resistant to penicillins, then tetracyclines, then cephalosporins, then fluoroquinolones — and so on, until nearly nothing works against them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “When bacteria are stressed, they turn on their S.O.S. system,” said David W. Graham, a professor of ecosystems engineering at Newcastle University in Britain and a pioneer in antibiotic-resistance testing. “It accelerates the rate at which they rearrange their genes and pick up new ones.” | ||

| + | Eight years ago, Dr. Ahammad, a former student of Dr. Graham, suggested testing Indian waters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Until then,” Dr. Graham said, “I had avoided India because | ||

| + | |||

| + | I thought it was one huge polluted mess.” With antibiotic-resistant bacteria so ubiquitous, it would be hard to design a good experiment — one with a “control,” someplace relatively bacteria-free. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We needed to find some place with clear differences between polluted and unpolluted areas,” Dr. Graham said. | ||

| + | That turned out to be the Ganges. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Healthy pilgrims, dangerous germs''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although it is officially sacred, the Ganges is also a vital, working river. Its numerous watersheds in the mountains, across the Deccan Plateau and its vast delta serve 400 million people — a third of India’s population — as a source of drinking water for humans and animals, essential for crop irrigation, travel and fishing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Twice a year, two of Dr. Ahammad’s doctoral students, Deepak K. Prasad and Rishabh Shukla, take samples along the whole river, from Gangotri to the sea, and test them for | ||

| + | organisms with drug-resistance genes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The high levels discovered in the river’s lower stretches were no surprise. But the researchers found bacteria with resistance genes even in the river’s first 100 miles, after it leaves Gangotri and flows past the next cities downstream: Uttarkashi, Rishikesh and Haridwar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | More important, the researchers found that the levels were consistently low in winter and then surged during the pilgrimage season, May and June. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tiny Gangotri is so high in the mountains that it closes in winter, made impassable by the snow. But in summer, the area’s population swells with hundreds of thousands of pilgrims. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because the district is sacred, no alcohol or meat may be sold there. Devout Hindus are often vegetarian and abstemious. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The riverside cities have wide flights of steps, called ghats, leading into the water, often with netting or guardrails. They help pilgrims safely immerse themselves and drink — a ritual that is supposed to wash away sins and hasten entry into paradise. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Souvenir stands sell plastic jugs so pilgrims can take Ganges water home to share. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The most famous of the Upper Ganges pilgrimage cities is Rishikesh. Its streets are lined with hotels with names like Holy River and Aloha on the Ganges. Besides pilgrims, Westerners pour in for the town’s annual yoga festival or to study in its many ashrams and ayurvedic medicine institutes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1968, the Beatles studied Transcendental Meditation there with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. In his pre-Apple days, Steve Jobs pursued enlightenment there. Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles have visited. | ||

| + | Adventure tourists also travel there. Rishikesh offers river-rafting, mountain trekking, zip lines and paintball tournaments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The population is about 100,000 in winter, but in the pilgrimage-vacation season it can swell to 500,000. The city’s sewage treatment plant can handle the waste of only 78,000 people, Dr. Ahammad said. The government deploys many portable toilets, but the slightest rainstorm can send sewage cascading into the river. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 2014, Dr. Graham and Dr. Ahammad found the clean-versus-dirty line in the Ganges to be at its starkest at Rishikesh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Upstream, the water was fairly clean both summer and winter, but downstream in summer, the levels of bacteria with drug-resistance genes were astounding. The levels of NDM-1 — a drug-resistance gene that was first discovered in India and whose first two initials stand for New Delhi — were 20 times higher. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | That finding has led the researchers to several conclusions. The resistant bacteria in the water had to have come from people — specifically, from their intestines. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Perhaps more intriguing, those people were fairly healthy — most were hale and hearty enough to be pilgrims, yoga students or river-rafters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Presumably, Dr. Ahammad and Dr. Graham explained, the healthy travelers “bad” gut flora were held in check by their “good” flora. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At least 1,000 bacterial species have been found colonizing human intestines. A healthy individual has at least 150 species, all competing with one another for space and food. | ||

| + | |||

| + | People can shed the bacteria they carry into the Ganges, Dr. Ahammad’s and Dr. Graham’s research shows. Then, if someone else picks them up, then falls ill and is given antibiotics, the person’s good bacteria can be killed and the bad ones have an opportunity to take over. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pilgrimage areas, Dr. Ahammad and Dr. Graham wrote, are | ||

| + | “potential hot spots for antibiotic-resistance transmission at large scales.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We are not telling people to stop rituals they’ve done for thousands of years,” Dr. Ahammad said. “But the government should do more to control the pollution and protect them.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | What will be required, he said, is an Indian equivalent of the Clean Water Act, which provided billions of federal dollars to build hundreds of sewage treatment plants across the United States. | ||

| + | |||

| + | And even that, he explained, would not be enough. While tertiary sewage treatment can kill or remove resistant bacteria, it doesn’t destroy free-floating DNA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “That technology hasn’t been invented yet,” said Mr. Shukla, who is working to invent it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''A continuing risk''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the meantime, pilgrims will continue to be at risk, trusting in the gods to protect them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Ganga is our mother — drinking her water is our fate,” said Jairam Bhai, a large, jovial 65-year-old food vendor who held two small jugs as he waited to descend into the water in Gangotri. “If you have faith, you are safe.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | “We don’t follow bacteria, we don’t think about it,” added Jagdish Vaishnav, a 30-year-old English teacher who said he swam and drank the water in Rishikesh, Haridwar and even in Varanasi, where torrents of raw sewage can be seen flowing into the river. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Devout Hindus go there to die so that they can be cremated on the ghats or on floating rafts and have their ashes strewn on the water to free them from the cycle of death and rebirth. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Up high in Gangotri, the priests on the banks say they are well aware of the dangers downstream. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Below Haridwar, I believe there are chances of disease,” said Basudev Semwal, 50. “That’s why we publicize that people should come here — because it’s cleaner.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | His companion, Suraj Semwal, 44, said the government should do more. If all Hindu religious figures could get together, they might be able to demand a cleanup, he said. But the many Hindu religious orders are not hierarchical like those of Roman Catholicism, which has a pope. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Everyone has their own voice, so they can’t speak together,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Canada, he said he had heard, “There is a river where you can get fined if you even touch it — and it’s just a river, not holy at all. Here we have a holy river, and it’s very dirty and nothing is being done.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India|GGANGA (GANGES), RIVER | ||

| + | GANGA (GANGES), RIVER]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|GANGA (GANGES), RIVER | ||

| + | GANGA (GANGES), RIVER]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Rivers|GGANGA (GANGES), RIVER | ||

| + | GANGA (GANGES), RIVER]] | ||

==Human excrement: 2019== | ==Human excrement: 2019== | ||

Revision as of 20:58, 28 February 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Sources include

The Ministry of Water Resources, Govt o India

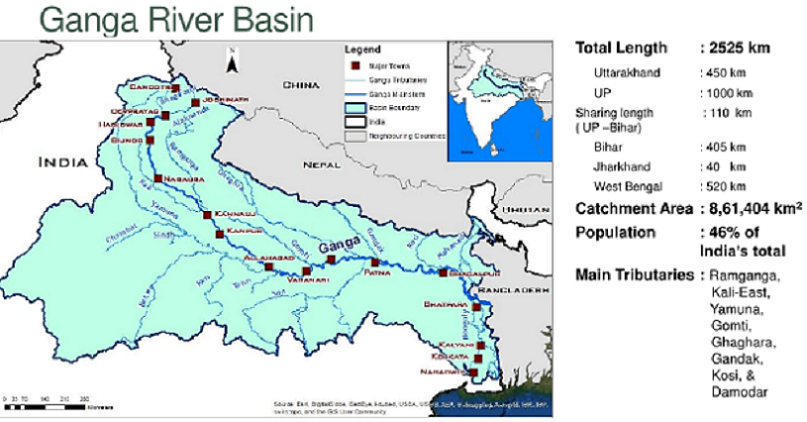

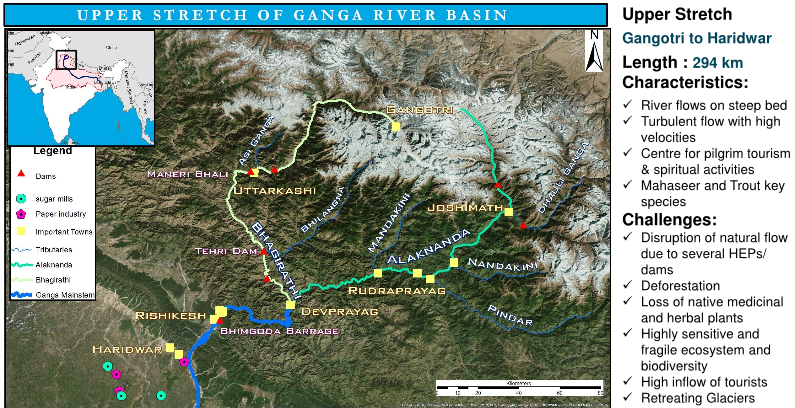

Route

See maps

Gomukh

Once upon a time not very long ago, say old timers, Gomukh, the snout of the Gangotri glacier --source of the Ganga river -extended as far as Gangotri town, located almost 18 km away. However, uncontrolled development activities including deforestation, rampant construction and unregulated flow of tourists (and the pollution caused by their vehicles) has caused the glacier -which is around 30-km long and between .5 to 2.5 km wide -to not just recede but also raised worries over the continuing health of the source of the country's most revered river. “Gangotri glacier has been under a state of continuous recession since 1935 . The Geological Survey of India which monitored the glacier from 1935 till 1996 found that the glacier retreated by 1147 metres, with an average rate of 19 mtryear between 1935 and 1996. The total area vacated by the glacier during 1935 to 1996 is estimated to be 5, 78,100 sq mtr,“ says DP Dobhal, scientist at the Centre For Glaciology, Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun.

A study carried out by the Uttarakhand Space Application Centre (USAC) between 2000 and 2016 found that the glacier receded almost 150 metres in just 16 years.“In 2000, the glacier retreated at the rate of 14 In partnership with metres each year; in 2012, by 12 metreyear, in 2015 by 10 metreyear and in 2016 by 20 metre per year,“ says Asha Thapliyal, scientist with USAC. She added that the Gangotri glacier is retreating “largely due to climate change and partially because of excessive human interference with tourists and devotees using the area quite frequently.“ “The snout of the glacier has become wider with fragmentation and the continuous melting,“ she told.

What is especially worrying scien tists is that the glacier's base is also thinning and has become more fragile.Kireet Kumar, scientist at the Almorabased GB Pant National Institute of Himalayan Environment and Sustainable Development (GBPNIHESD) who has extensively researched the glacier, terms this as “the most devastating effect of climate change.“ “Gangotri is a gigantic glacier which because of its size, takes longer to show any change with regard to climate change. However, the impact of climate change on it becomes perceptible through small glacier tributaries which are situated above it.These tributary glaciers melt faster due to increase in temperature and thus, water generated from them flow down and seep into the crevasses of Gangotri glacier. This is resulting in a situation where the glacier is melting from the bottom.“

He added that “the water melting from the glacier bottom has not increased the water flow emanating from the glacier which shows that the water is evaporating due to temperature increase.“ “Since the tributaries situated on the right side of Gangotri glacier are hitting its right bottom, therefore its right side corner has receded the most.This ultimately means breakage and loss of storage of water,“ says Kumar.

Scientists warn that if the situation continues like this, there will be a severe water shortage for the Ganga at its source. “The process of Gangotri glacier receding has been ongoing for last 250 years at a gradual pace but has picked up pace in the last few decades. If it continues like this, it will soon lead to a situation when there will be serious scarcity of water. Hence, it is very important to strike a balance with the environment,“ says Dobhal.

Seconding these views, Harshwanti Bisht, an Arjuna award winning mountaineer who now helms the `Save Gangotri Project' that has been working in the Gangotri area for over two decades, says, “ The seriousness of the situation can be gauged by viewing the earlier photographs of Gangotri glacier and comparing them with the present. If one sees the picture of the glacier clicked by British photographer Samuel Burns in 1866-67 and compares it with present-day photos, it is evident that Gangotri glacier has shrunk by at least 4 to 5 km which is quite a lot.“

She says that the situation can “still be salvaged if more trees are planted.“

“In the past few years, the intensity of rainfall has increased in comparison to snowfall. This results in intense landslide activities in the region and an increase in the melting rate of the glacier.There is an urgent need to plant more trees in the area to arrest this.“

Impact of debris on Gaumukh

Debris alters course of Ganga near Gaumukh, Oct 17 2017: The Times of India

The snout of the Gangotri glacier -Gaumukh -from where the Ganga river emerges has been so impacted by debris falling from nearby areas due to landslides that it has altered the course of the river. This startling discovery was made during a recently-organised trek from Gangotri to Gaumukh (of which TOIwas a part) during which environmentalists and scientists found that not only have cracks appeared in the glacier situated at a height of around 13,200 feet (4,023 m), but also a lake-like structure has formed here from where the main stream of the Ganga (known as Bhagirathi) is flowing. Scientists found that because of the formation of the lake, the river is now flowing from the left side of the glacial snout instead of straight as was the case earlier. Navin Juyal, senior scientist at the Physical Research Laboratory , Ahmedabad, who was part of the trek, told TOI that if the Ganga continues to flow in its changed course from the lake, it might eventually lead to collapse of Gaumukh.

“A stream emanating from a tributary glacier was blocked probably due to the heavy rain which occurred in the month of July . This impounded stream got breached and released enormous amount of paraglacial debris in the form of alluvial fan, which changed the course of the river. If the glacier continues to melt and water continues to follow on the path of paraglacial debris touching the glacier snout, then large pieces of the snout will collapse,“ said Navin Juyal, senior scientist, Physical Research Laboratory , Ahmedabad who was part of the 61-member trekking team that visited the area between October 11 and 14.

Pictures clicked by Gulab Singh Negi who has been vis Singh Negi who has been visiting Gaumukh almost every year since 1970s (to capture the change in the glacial snout through photographs), show a drastic change in the appearance of Gaumukh.Not only do the pictures support the claims of the crack that has appeared in the snout but also show how the debris from the nearby mountains has changed the course of Ganga leading to the formation of a lake here.

The route in 1965

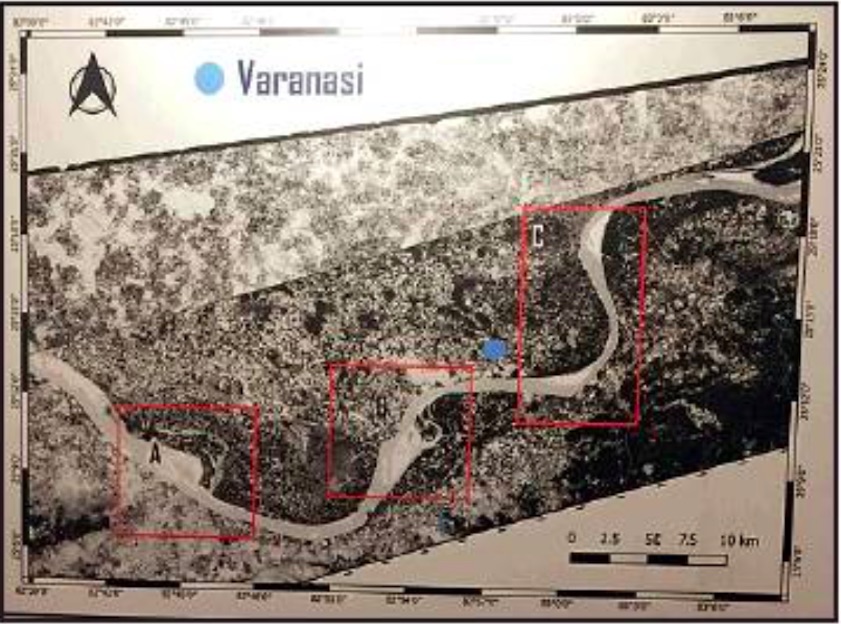

From: Vishwa Mohan, Scientists using US intel pic to restore ‘Ganga of the past’, November 16, 2018: The Times of India

Indian scientists are using declassified satellite images of US military intelligence to “reconstruct the river Ganga of the past”. The images were originally used for reconnaissance and to produce maps for the American intelligence agencies including CIA.

The classified military satellite system (code-named CORONA) had acquired photographic images of the entire Ganga river basin during 1960s.

According to information available on website of the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the first generation of the US photo intelligence satellites collected more than 8,60,000 images of the Earth’s surface between 1960 and 1972. The classified military satellite systems acquired photographic images from space and returned the film to Earth for processing and analysis. The images were declassified in 1995.

“The first successful CORONA mission was launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in 1960. The satellite acquired photographs with a telescopic camera system and loaded the exposed film into recovery capsules. The capsules or buckets were de-orbited and retrieved by aircraft while the capsules parachuted to earth. The exposed film was developed and the images were analysed for a range of military applications,” said the USGS on its website.

Aquatic life

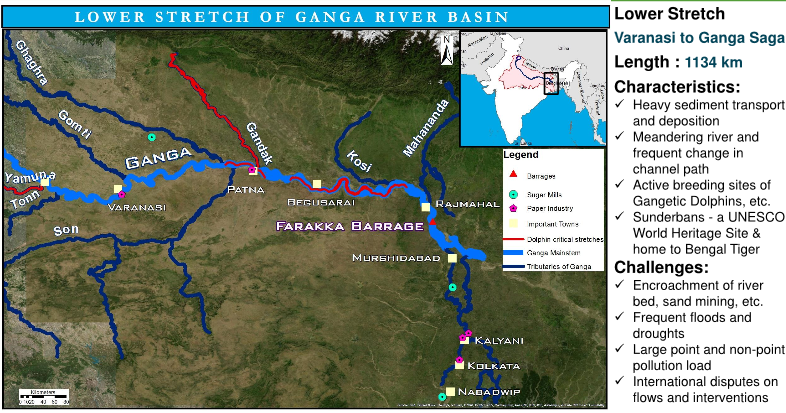

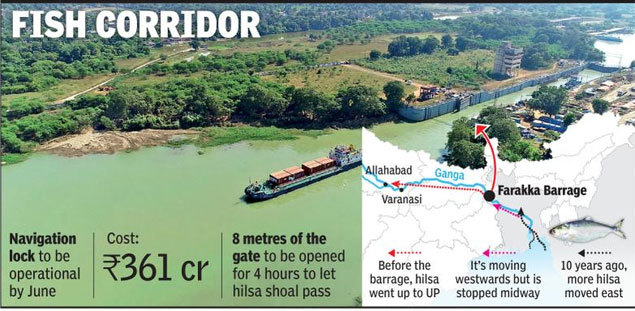

Fish: Blocked at Farakka in 70s; unblocked 2019

Dipak K Dash, February 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Dipak K Dash, February 9, 2019: The Times of India

In June 2016, someone forked out Rs 22,000 for a 4 kg hilsa in Bengal’s Howrah. The fish, that had swum down from Myanmar, was indeed a prize catch: it’s rare to find hilsas that large. But the price the shining fish fetched at a bustling wholesale market in Howrah was the ultimate gastronomic measure of how far a fish lover would go to have the bony hilsa on his plate.

Now, after a gap of over 40 years, the hilsa will be able to swim down the Ganga all the way up to Allahabad this monsoon.

The migration of Hilsa till Allahabad had been possible till a barrage was built across the Ganges at Farakka in Bengal in the 70s. The barrage came with a navigation lock that blocked the free movement of Hilsas.

This lock has now been redesigned to ensure smooth and safe migration of the hilsa shoal during the three mating seasons, particularly during monsoon. A navigation lock is a device that is used to raise and lower boats and ships between stretches of water on a river.

“We will open the gates for only eight metres and between 1 am and 5 am, which is the preferred time when Hilsa seeks passage. This provision has been made in consultation with ICARCentral Inland Fisheries Research Institute, Central Water Commission and Farraka Barrage Project Authority. We have designed this inhouse and have saved about Rs 100 crore,” Inland Waterway Authority of India (IWAI) vice-chairman Pravir Pandey told TOI.

Hilsa has a history of migrating from Bangladesh to Allahabad down the Ganga. Though it’s a salt-water fish, it migrates from the Bay of Bengal to the sweet waters of the Ganges. “Fish often disperse widely over large areas while feeding and spawning. This hilsa migration will lead to an increase in its production in the region. This will also increase the river’s biodiversity and boost the economy of local fishermen,” a shipping ministry spokesperson said.

In recent years, overall catch of hilsa has reduced as overfishing, pollution and spawning have taken their toll on fish stocks. The navigation lock being built at a cost of Rs 361 crore as a part of Jal Marg Vikas Pariyojna will be operational from June.

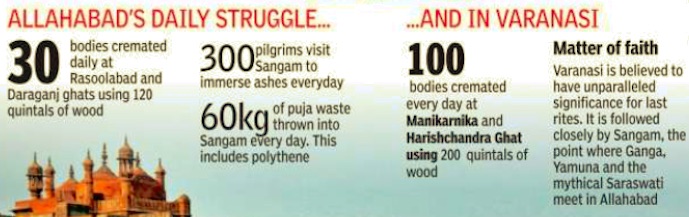

Cremation in Kashi, ashes in the Ganga

The impact, as in 2017

Rashi Lal, Ganga continues to carry burden of faith, September 28, 2017: The Times of India

CHANGE IN DISCOURSE? Experts Say A Major Threat To The River Is Ritualism; Centre and State Need To Promote Rational Practices

In Uttar Pradesh, they don't say `Ganga'. For them, it's `Gangaji,' a source of their suste nance and salvation. It's with this belief that scores throng the ghats in Varanasi to perform rituals and immerse ashes in the river.

Arjun Maurya, a resident of neighbouring Jaunpur, has just cremated his father at Manikarnika Ghat. He says, “Cremation in Kashi and immersing ashes in the Ganga have been a matter of faith for generations.It is believed that the body is made of `panch tatva' (five elements). How will Ganga's water, which is one of the five, get polluted if these elements mix?“ At Dashashwamedh Ghat, Vimlesh Kumar Mehra, who has come all the way from Jharkhand to immerse the ashes of his father, says, “Ganga descended on earth to provide salvation to people... Last rites do not pollute the Ganga, sewage and industrial effluents do.“

This the challenge that faith poses to efforts aimed at rejuvenating the river. Experts say you can stop a polluting industry with a court order, but how do you stop a man who has lost his mother from acting on his belief that immersing her ashes in the Ganga will get her moksha?

This burden of faith has been borne by the Ganga for centuries. Ages ago, the rationale was that the ashes-a collection of calcium, phosphates and other minerals from the human body--made the water mineralrich. And that was a boon for farmlands.

“Today , the ritual is misunderstood, and we see half-burnt bodies thrown into the river.Even our scriptures prohibit immersion of bodies in rivers,“ says Lucknow-based river scientist Venkatesh Dutta. Nearly 33,000 bodies are cremated by the riverbanks in Varanasi alone every year. This requires 16,000 tonnes of wood and generates 800 tonnes of ashes.

Former geology professor at Lucknow University IB Singh, who has worked extensively on the Ganga, has a stark insight.“If you live on faith, the river will die. Faith was okay when population was low. Now, it's not a religious problem but a social one. If we talk about scriptures, even defecation in the Ganga is prohibited. But with so many living on the banks of rivers and jostling for space, where will one go?“ Today , Varanasi's population has grown to 36 lakh, while it's 59 lakh in Allahabad-that's part of the matrix which the NDA government has to weave into its flagship initiatives including Namami Gange and the dedicated Ganga rejuvenation wing. It will, obviously, take more than a strong dose of rationality to turn the course.

However, social scientist and former JNU professor Purushottam Agarwal says that when it comes to faith, awareness cannot be imposed. “A sustained campaign not on sentiment but rationality needs to be launched with focus on environment,“ he says. “Unfortunately , anybody who talks about religion is seen as hurting sentiments.“

Agreeing with him, Parveen Kaswan, an Indian Forest Service officer who has campaigned for the issue, says one can't raise questions on faith.According to him, the best way to bring about change is to associate faith with cleaning or protecting the river. On happy occasions like birth or marriage, he says people should be persuaded to plant a tree next to the river or clean it.

One BJP government in an adjoining state has already taken the lead in propagating a more rational approach to the question. Madhya Pradesh chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan, earlier this year, urged ritualists to desist from immersing ashes in the Narmada. And he said if ashes had to be immersed, make do with a pinch and scatter the rest in your fields.

Last year, the National Green Tribunal had said religious leaders, governments and civic agencies must help change mindsets and promote ecofriendly methods of cremation.The Ganga may well prove to be a litmus test for the Yogi Adityanath regime.

Healing properties

Does not putrefy easily despite pollution

Shimona Kanwar, `Polluted Ganga still has healing touch', Sep 25 2016 : The Times of India

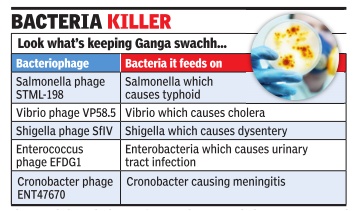

Until now, it was believed that the healing properties of the Ganga were merely the stuff of myths. However, scientists from the Institute of Microbial Technology (Imtech), Chandigarh, have for the first time come forward with scientific evidence that the water of Ganga does not putrefy easily . They have identified new viruses, or bacteriophages, which mimic bacteria in the river's sediment and eat them up.

The scientific world has always been baffled by the antiseptic properties of Ganga's waters. In 1896, British physician E Hanbury Hankin observed that cholera microbes died within three hours in its water, but thrived in distilled water. This remained hypothetical until Imtech experts found the new viruses.

Imtech is one of the laboratories of the CSIR. The study has revealed 20 to 25 types of bacteriophages in the river which can fight microorganisms that cause diseases like tuberculosis, pneumonia, cholera and urinary tract infection, among others. “We analysed the viral metagenomes in sediments of the Ganga and found different types of phages, said Dr Shanmugam Mayilraj, senior principal scientist at Imtech. He said the sediments house several novel viruses, which were never reported earlier. These are active against certain bacterial strains and can be used against multidrug resistant infections.

The team collected samples from the highly polluted Haridwar-Varanasi stretch.Also part of the project were National Environment Engineering Research Institute co-ordinating lab, National Botanical Research Institute, Indian Institute of Toxicology Research and Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants.

Impact on lives

Floods destroy lives in Bijnor

The Times of India, August 25, 2016

Harveer Dabas

Every year at least 25 villages on the banks of the Ganga get flooded during the monsoon season due to the lack of an embankment. Apart from facing economic hardships because of crop loss and soil erosion, villagers here also say that they are now finding it difficult to get brides for youths of marriageable age.Families from other villages outrightly reject any proposal for marriage, saying that their daughters would rather sit at home than get married to a person who lives in a flooded village.

The Ganga, which enters Bijnor district from Uttarakhand, was a blessing for the villagers living near the river and annual flooding rendered the soil fertile. The river used to flow about 3-4 km away from the Bijnor's villages on Muzaffarnagar-Bijnor border. Farmers were prosperous and lived a happy life. But since the past several years, the situation has changed. The Ganga has become a nightmare for the farmers here, as the river is continuously changing its course and rapid erosion is threatening the existence of some villages here. At present, the Ganga's main stream flows ve ry close to these village.

During monsoon season, the Ganga floods about 25 villages here, including Gauspur, Simli, Fatehpur, Keharpur, Rajarampur, Kundanpurtip, Meerapur, Daibalgarh, Ravli, Brahampuri, Rampur Thak ra, Jivanpuri, etc, destroying crops, agricultural land and houses.

Pollution

The extent in 2017, and issues

Jacob Koshy, October 21, 2017: The Hindu

How polluted is the river?

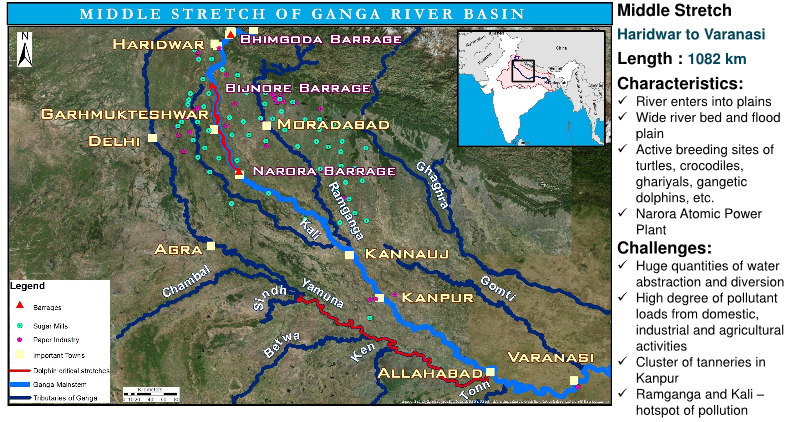

Coursing about 2,500 km, the Ganga is the longest river within India’s borders. Its basin constitutes 26% of the country’s land mass (8,61,404 sq. km.) and supports 43% of India’s population. Even as its basin traverses 11 States, five States are located along the river’s main stem spanning Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Bihar and West Bengal. Much of the river’s pollution load — from chemical effluents, sewage, dead bodies, and excreta — comes from these States. In the Ganga basin, approximately 12,000 million litres per day (mld) of sewage is generated, for which there is now a treatment capacity of just 4,000 mld. Particularly, on the stretch spanning Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, approximately 3,000 mld of sewage is discharged, and a treatment capacity of just 1,000 mld has been created to treat it. Though the contribution of industrial pollution, volume-wise, is about 20%, its toxic and non-biodegradable nature has a disproportionate impact. The industrial pollutants largely emanate from tanneries in Kanpur, distilleries, paper mills and sugar mills in the Kosi, Ramganga and Kali river catchments. Then there is the municipal sewage which, at about a billion litres a day, generates 80% of the pollution load. This spans a wide range, from run-off in rural settlements to carcasses floated down the river.

What is the government doing?

The BJP included the cleaning of the Ganga in its 2014 election manifesto. The Narendra Modi government earmarked ₹20,000 crore for the clean-up and promised that the river would be clean by 2020. Former Union Minister for Water Resources Uma Bharti said the river would be clean by 2018 but the new Minister, Nitin Gadkari, indicated that this deadline was unlikely to be met. He, however, said the river would be “noticeably clean” by March 2019.

What has been done so far? (till October 2017)

The government has set up an empowered authority called the National Mission for Clean Ganga. This is a dedicated team of officers who are responsible for disbursing the ₹20,000 crore fund towards a variety of projects that involve setting up of sewage treatment plants (STPs), replacing woodfired crematoriums with electric ones or those that use fuel more efficiently, setting up biodiversity parks that will enable native species — from the Gangetic river dolphin to rare turtles — to replenish their numbers and planting trees to improve the water table in the surrounding regions and prevent soil erosion. The authorities focussed on having trash skimmers ply along the river and collecting garbage, and improving crematoria. However the big task — of installing sewage treatment plants — is grossly delayed. Barely ₹2,000 crore of the ₹20,000 crore has been spent so far. The government says this has taken time because it wanted to put in place an extremely transparent tendering process. It has also established a system called the hybrid-annuity model, used in commissioning highways, for selecting firms that will manage STPs. Under this, firms would be given nearly half the money upfront to set up a plant and the rest (with a profit margin included) at regular intervals, provided they meet certain criteria over 15 years. Sixty-three sewerage management projects are being implemented in Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal. Last week, STPs to treat 1187.33 mld were cleared for Hardwar and Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh.

What are ‘clean river’ criteria?

The ultimate objective, for the river to be clean, would be to ensure that the coliform bacteria level, biochemical oxygen demand, pH and dissolved salts remain within the standards prescribed by the Central Pollution Control Board.

2018: Water quality, especially in riverside towns

From: October 25, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

2018- the quality of water in the Ganga, especially in riverside towns

1.3bn litres of waste flows into Ganga every day

From: Radheshyam Jadhav, 1.3bn litres of waste flows into Ganga every day, April 20, 2018: The Times of India

The government’s flagship National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) has created sewage treatment capacity of just over 259 million litres per day (MLD), which is about 11% of the 2,311 MLD the programme seeks to create. With sewage treatment capacity being a fraction of what is required, over 1,300 MLD of sewage continues to flow into the main stem of the Ganga.

Overall, the Mission has 193 projects including 100 sewage treatment projects on its agenda and has completed 49 projects utilizing 21% of the funds sanctioned for all projects.

Till March 2018, it had completed 20 of the 100 sewage treatment projects.

The cabinet approved the Namami Gange programme on May 13, 2015 as a comprehensive approach to rejuvenate the Ganga by inclusion of all its tributaries under one umbrella at a total cost of Rs 20,000 crore for five years. According to the data available on the Mission website, of the 100 sewage treatment projects, 43 projects are old ones on which work was started before 2015 while the remaining 57 are new initiatives. Of the 43 old projects, 17 have been completed with treatment capacity of 259 MLD. Three of the new projects have been completed, but with related works not being completed these have not added to the capacity as yet.

The sanctioned cost for sewage infrastructure is about Rs 16,600 cr, making it by far the largest component of the overall programme. Of this, barely Rs 2,814 cr or 17% has been utilized so far.

Data presented in the Lok Sabha by the minister of state for water resources, river development and Ganga rejuvenation shows that according to the Central Pollution Control Board, the total sewage generated from major towns/ cities in the catchment of the Yamuna is 5,236 MLD, whereas the treatment capacity developed is 3,805 MLD. Estimated sewerage generation from 97 towns located on the main stem of the Ganga is 2,953 MLD against the available treatment capacity of 1,584 MLD.

Rajiv Kishore, executive director (administration) with the NMCG said that creation of sewage treatment capacity takes 2-2.5 years to finish. NMCG was registered as a society in August, 2011. “After that it took some time to create a set up and posting of people. . You can’t expect sewage treatment plants to start functioning within two years. . By this year-end, some projects will start treating sewage” said Kishore.

Less than 33% of urban waste is processed

Dipak Dash, October 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: Dipak Dash, October 22, 2018: The Times of India

Less than onethird of the municipal solid waste generated in the 97 cities and towns along Ganga is processed, posing a major challenge to clean the river. The urban affairs ministry has proposed to focus on segregating wet and dry waste to deal with the crisis rather than waiting for new waste processing plants to be ready.

The ministry shared the details of the sold waste generated in these cities during a presentation before water resources and Ganga rejuvenation minister Nitin Gadkari. According to the ministry data, about 11,625 tonnes of solid waste is generated from cities and towns along the river. West Bengal has the maximum share of generating about 6,132 tonnes of waste per day, more than half of the total municipal refuse.

UP has the second highest share of 3,275 tonnes of garbage generated daily while Bihar generates about 15% of the total solid waste. Data show that West Bengal has been lagging behind in comparison to other four states through which Ganga passes. The state government is yet to prepare the detailed project reports for processing 4,884 tonnes of garbage while existing plants can treat 653 tonnes of municipal waste per day. The urban affairs ministry has proposed decentralised composting of wet waste in these cities and towns, which will take care of about 40-60% of the total municipal refuse generated daily. Another 20-30% of the waste, which is dry, can be recycled or reused and the rest 5-10% of the construction and inert waste processed for building materials.

2016-19: water quality worsens

Binay Singh, Ganga water quality has worsened in 3 yrs: Study, March 15, 2019: The Times of India

From: Binay Singh, Ganga water quality has worsened in 3 yrs: Study, March 15, 2019: The Times of India

The Rs 20,000-crore “Namami Gange” project to “conserve, clean and rejuvenate” the Ganga river seems to have failed to achieve its target. On the contrary, analysis of data collected by the city-based Sankat Mochan Foundation (SMF) has revealed a significant rise in coliform bacteria and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), important parameters to evaluate water quality.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had set an ambitious 2019 deadline to achieve results on nirmalta (cleanliness) of Ganga when he launched the project in May 2015. Union minister Nitin Gadkari last year extended the deadline to March 2020.

SMF, a Varanasi-based NGO, has been monitoring the quality of Ganga water since the launch of the Ganga Action Plan by then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1986. Working as a watchdog for the cause of the Ganga, SMF has established its own laboratory to analyse the samples of Ganga water on a regular basis.

Coliform in Ganga water at alarming levels

Data collected by SMF’s Ganga Laboratory at Tulsi Ghat here has painted a gloomy picture of the Ganga’s health due to high bacterial pollution. Coliform organisms should be 50MPN (most probable number)/100ml or less in drinking water and 500MPN/100ml in outdoor bathing water, while BOD should be less than 3mg/l. According to SMF data, faecal coliform count rose from 4.5 lakh (upstream at Nagwa) and 5.2 crore (downstream in Varuna) in January 2016 to 3.8 crore (upstream) and 14.4 crore (downstream) in February 2019.

“Similarly, BOD level has risen from 46.8-54mg/l to 66-78mg/l during January 2016-February 2019. Besides, the level of dissolved oxygen (DO), which should be 6mg/l or more, has gone down from 2.4mg/l to 1.4mg/l during this period. High presence of coliform bacteria in Ganga water is alarming for human health,” said SMF president and IIT-BHU professor V N Mishra, who is also the mahant of the famous Sankat Mochan temple.

“Faecal coliform is present in the gut and faeces of warmblooded animals. Consequently, E coli is considered to be the species of coliform bacteria that is the best indicator of faecal pollution and possible presence of disease-causing pathogens,” said noted environmental scientist and former BHU professor B D Tripathi.

A slight improvement was seen in tapping discharge of sewage into the Ganga during this period.

Rebuttal: ‘Ganga pollution rise claim unscientific’

‘Ganga pollution rise claim unscientific’, March 16, 2019: The Times of India

Strongly rebutting claims of a substantial increase in level of pollutants in Ganga in a report by Varanasi-based Sankat Mochan Foundation, the National Mission for Clean Ganga said such high levels of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) have never been reported for the river.

Questioning the capacity of the Foundation to carry out such tests, the NMCG — a central agency which has been implementing the government’s ambitious Ganga rejuvenation programme — said the high level of BOD claimed were not “scientific at all” as such a scenario could lead to sudden depletion of Dissolved Oxygen (DO) level severely impacting aquatic life. Only the Central Pollution Control Board had the wherewithal to monitor pollution along the length of the river.

Referring to CPCB data of the last six years, the Mission said the DO level has, in fact, been found to be within “acceptable limits” of notified primary water quality criteria for bathing. The BOD level should be less than 3 mg/L, DO should be 5 mg/L or more and desirable faecal coliform should be 500 MPN (most probable number)/100 ml with maximum permissible level being 2,500 MPN/100ml.

The Foundation has gone by data collected by its laboratory at Tulsi Ghat in Varanasi and claimed that the BOD level has increased from 46.8-54 mg/L to 66-78 mg/L during January 2016 to February 2019. Similarly, the NGO claimed faecal coliform in the river at Varanasi have increased from 4.5 lakh (upstream at Nagwa) and 5.2 crore (downstream at Varuna) in January, 2016 to 3.8 crore (upstream) and 14.4 crore (downstream) in February, 2019. Calling these claims “incorrect”, the NMCG flagged the scientific data of the CPCB which carried out continuous water quality monitoring at two locations in Varanasi.

It said, “Analysis of water quality monitoring data of CPCB for these two stations located on main stem of Ganga in Varanasi for the month of January for period 2016-19 indicates that minimum value of DO varied between 6.7 to 7.6 mg/L and indicated healthy state of river.”

Germs impervious to common medicines / 2019

Dec 23, 2019 The New York Times

Deepak K. Prasad, left, collected a water sample, while Rishabh Shukla, right, checked the temperature of the Ganges at Byasi, India, in the Himalayas.

GANGOTRI, India — High in the Himalayas, it’s easy to see why the Ganges River is considered sacred.

According to Hindu legend, the Milky Way became this earthly body of water to wash away humanity’s sins. As it drains out of a glacier here, rock silt dyes the ice-cold torrent an opaque gray, but biologically, the river is pristine — free of bacteria.

Then, long before it flows past any big cities, hospitals, factories or farms, its purity degrades. It becomes filled with a virulent type of bacteria, resistant to common antibiotics. The Ganges is living proof that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are almost everywhere. The river offers powerful insight into the prevalence and spread of drug-resistant infections, one of the world’s most pressing public health problems. Its waters provide clues to how these pathogens find their way into our ecosystem.

Winding over 1,500 miles to the Bay of Bengal, Ma Ganga — “Mother Ganges”— eventually becomes one of the planet’s most polluted rivers, a mélange of urban sewage, animal waste, pesticides, fertilizers, industrial metals and rivulets of ashes from cremated bodies.

But annual tests by scientists at the Indian Institute of Technology show that antibiotic-resistant bacteria appear while the river is still flowing through the narrow gorges of the Himalayan foothills, hundreds of miles before it encounters any of the usual suspects that would pollute its waters with resistant germs.

The bacterial levels are “astronomically high,” said Shaikh Ziauddin Ahammad, a professor of biochemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology. The only possible source is humans, specifically the throngs of ritual bathers who come to wash away their sins and immerse themselves in the waters.

India’s resistance problem

Beyond the Ganges, India has some of the highest antibiotic-resistance rates in the world, according to a 2017 report from the government’s Ministry of Science and Technology.

Tests showed that about 70 percent of four bacteria species commonly found in hospital patients were resistant to typical first-line antibiotics. Between 12 percent and 71 percent — depending on the species tested — were also resistant to carbapenems, a class of antibiotics once considered the last line of defense.

Other studies confirm the danger. An article in Lancet Infectious Diseases found that about 57 percent of infections in India with Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common bacterium, were carbapenem-resistant.

But where exactly do these armies of drug-resistant germs come from? Are they already everywhere — in the soil beneath our feet, for example? Do they emerge in hospitals, where antibiotics are heavily used?

Are they bred in the intestines of livestock on factory farms? Do they arise in the fish, plants or plankton living in lakes downstream from pharmaceutical factories?

Or are the germs just sitting inside the patients themselves, waiting for their hosts to weaken enough for them to take over?

Research now being done in India and elsewhere suggests an answer to these questions: Yes, all of the above.

But how drug-resistant bacteria jump from one human to another outside of a hospital setting is the least-understood part of the process, and that is why the findings from the Ganges are so valuable.

Origins of drug-resistant germs

Antibiotic-resistance genes are not new. They are nearly as old as life itself.

On a planet that is about 4.5 billion years old, bacteria appeared about 3.8 billion years ago. As they fed on one other — and later on molds, fungi, plants and animals — their victims evolved genes to make bacteria-killing proteins or toxins, nature’s antibiotics. (Penicillin, for example, was discovered growing in mold.)

The bacteria, in turn, evolved defenses to negate those antibiotics. What modern medicine has done, scientists say, is put constant Darwinian pressure on bacteria.

Outside the body, they face sunlight, soap, heat, bleach, alcohol and iodine. Inside, they face multiple rounds of antibiotics. Only the ones that can evolve drug-resistance genes — or grab them from a nearby species, which some bacteria can do — will survive.

The result is a global bout of sudden-death elimination at a microscopic level. Bacteria once susceptible to all families of antibiotics have become resistant to penicillins, then tetracyclines, then cephalosporins, then fluoroquinolones — and so on, until nearly nothing works against them.

“When bacteria are stressed, they turn on their S.O.S. system,” said David W. Graham, a professor of ecosystems engineering at Newcastle University in Britain and a pioneer in antibiotic-resistance testing. “It accelerates the rate at which they rearrange their genes and pick up new ones.” Eight years ago, Dr. Ahammad, a former student of Dr. Graham, suggested testing Indian waters.

“Until then,” Dr. Graham said, “I had avoided India because

I thought it was one huge polluted mess.” With antibiotic-resistant bacteria so ubiquitous, it would be hard to design a good experiment — one with a “control,” someplace relatively bacteria-free.

“We needed to find some place with clear differences between polluted and unpolluted areas,” Dr. Graham said. That turned out to be the Ganges.

Healthy pilgrims, dangerous germs

Although it is officially sacred, the Ganges is also a vital, working river. Its numerous watersheds in the mountains, across the Deccan Plateau and its vast delta serve 400 million people — a third of India’s population — as a source of drinking water for humans and animals, essential for crop irrigation, travel and fishing.

Twice a year, two of Dr. Ahammad’s doctoral students, Deepak K. Prasad and Rishabh Shukla, take samples along the whole river, from Gangotri to the sea, and test them for organisms with drug-resistance genes.

The high levels discovered in the river’s lower stretches were no surprise. But the researchers found bacteria with resistance genes even in the river’s first 100 miles, after it leaves Gangotri and flows past the next cities downstream: Uttarkashi, Rishikesh and Haridwar.

More important, the researchers found that the levels were consistently low in winter and then surged during the pilgrimage season, May and June.

Tiny Gangotri is so high in the mountains that it closes in winter, made impassable by the snow. But in summer, the area’s population swells with hundreds of thousands of pilgrims.

Because the district is sacred, no alcohol or meat may be sold there. Devout Hindus are often vegetarian and abstemious.

The riverside cities have wide flights of steps, called ghats, leading into the water, often with netting or guardrails. They help pilgrims safely immerse themselves and drink — a ritual that is supposed to wash away sins and hasten entry into paradise.

Souvenir stands sell plastic jugs so pilgrims can take Ganges water home to share.

The most famous of the Upper Ganges pilgrimage cities is Rishikesh. Its streets are lined with hotels with names like Holy River and Aloha on the Ganges. Besides pilgrims, Westerners pour in for the town’s annual yoga festival or to study in its many ashrams and ayurvedic medicine institutes.

In 1968, the Beatles studied Transcendental Meditation there with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. In his pre-Apple days, Steve Jobs pursued enlightenment there. Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles have visited. Adventure tourists also travel there. Rishikesh offers river-rafting, mountain trekking, zip lines and paintball tournaments.

The population is about 100,000 in winter, but in the pilgrimage-vacation season it can swell to 500,000. The city’s sewage treatment plant can handle the waste of only 78,000 people, Dr. Ahammad said. The government deploys many portable toilets, but the slightest rainstorm can send sewage cascading into the river.

In 2014, Dr. Graham and Dr. Ahammad found the clean-versus-dirty line in the Ganges to be at its starkest at Rishikesh.

Upstream, the water was fairly clean both summer and winter, but downstream in summer, the levels of bacteria with drug-resistance genes were astounding. The levels of NDM-1 — a drug-resistance gene that was first discovered in India and whose first two initials stand for New Delhi — were 20 times higher.

That finding has led the researchers to several conclusions. The resistant bacteria in the water had to have come from people — specifically, from their intestines.

Perhaps more intriguing, those people were fairly healthy — most were hale and hearty enough to be pilgrims, yoga students or river-rafters.

Presumably, Dr. Ahammad and Dr. Graham explained, the healthy travelers “bad” gut flora were held in check by their “good” flora.

At least 1,000 bacterial species have been found colonizing human intestines. A healthy individual has at least 150 species, all competing with one another for space and food.

People can shed the bacteria they carry into the Ganges, Dr. Ahammad’s and Dr. Graham’s research shows. Then, if someone else picks them up, then falls ill and is given antibiotics, the person’s good bacteria can be killed and the bad ones have an opportunity to take over.

Pilgrimage areas, Dr. Ahammad and Dr. Graham wrote, are “potential hot spots for antibiotic-resistance transmission at large scales.”

“We are not telling people to stop rituals they’ve done for thousands of years,” Dr. Ahammad said. “But the government should do more to control the pollution and protect them.”

What will be required, he said, is an Indian equivalent of the Clean Water Act, which provided billions of federal dollars to build hundreds of sewage treatment plants across the United States.

And even that, he explained, would not be enough. While tertiary sewage treatment can kill or remove resistant bacteria, it doesn’t destroy free-floating DNA.

“That technology hasn’t been invented yet,” said Mr. Shukla, who is working to invent it.

A continuing risk

In the meantime, pilgrims will continue to be at risk, trusting in the gods to protect them.

“Ganga is our mother — drinking her water is our fate,” said Jairam Bhai, a large, jovial 65-year-old food vendor who held two small jugs as he waited to descend into the water in Gangotri. “If you have faith, you are safe.”

“We don’t follow bacteria, we don’t think about it,” added Jagdish Vaishnav, a 30-year-old English teacher who said he swam and drank the water in Rishikesh, Haridwar and even in Varanasi, where torrents of raw sewage can be seen flowing into the river.

Devout Hindus go there to die so that they can be cremated on the ghats or on floating rafts and have their ashes strewn on the water to free them from the cycle of death and rebirth.

Up high in Gangotri, the priests on the banks say they are well aware of the dangers downstream.

“Below Haridwar, I believe there are chances of disease,” said Basudev Semwal, 50. “That’s why we publicize that people should come here — because it’s cleaner.”

His companion, Suraj Semwal, 44, said the government should do more. If all Hindu religious figures could get together, they might be able to demand a cleanup, he said. But the many Hindu religious orders are not hierarchical like those of Roman Catholicism, which has a pope.

“Everyone has their own voice, so they can’t speak together,” he said.

In Canada, he said he had heard, “There is a river where you can get fined if you even touch it — and it’s just a river, not holy at all. Here we have a holy river, and it’s very dirty and nothing is being done.”

Human excrement: 2019

Shobita Dhar, November The Times of India

In 21 priority cities and towns along the Ganga, 60% of the population’s excreta is directly or indirectly dumped into the river, causing water pollution, says a study by the Centre of Science and Environment (CSE). It maps the entire route of faecal waste from the start to end in places including Rishikesh, Bijnor, Kanpur, Varanasi, Prayagraj, Patna and Haldia.

The study, which was conducted over a period of three years, has been presented to the National Mission for Clean Ganga in a bid to demonstrate the “breakdown in sanitation value chains” through a data-driven approach. In cities with more than 5 lakh population — Kanpur, Prayagraj, Varanasi and Patna — 52% of the faecal sludge produced is not safely managed.

It is worse in smaller towns with population between 1.2-5 lakh, like Mirzapur and Farukkhabad, where 84% of the sludge remains untreated. In these towns, 85% of the population is not connected to sewerage network and is dependent on onsite sanitation systems like septic tanks and pits. From there, a major chunk of the sludge ends up in open drains, nullahs, or open fields, and then into the river. This untreated sludge also seeps down to the ground water, which then finds its way back to households.

Government efforts to save the Ganga

Construction on Ganga banks in Uttarakhand banned

The Times of India, Nov 06 2015

Sharma Seema

NGT bars construction on Ganga banks in U'khand

The National Green Tribunal in Nov 2015 virtually barred construction of buildings 200 metres along the banks of the Ganga in Uttarakhand till further orders to protect pollutants from being discharged into the river. “We direct that no corporation, authority or panchayat shall grant permission for construction of building, houses, hotels or any structures within 200 metres of shore of river Ganga at the highest flood line without prior approval from the tribunal,“ a bench headed by NGT chairperson Swatanter Kumar said. The panel's direction came on a petition filed by advocate M C Mehta who sug gested that in Western countries rivers are protected from pollution by creating a buffer zone on the banks where no construction is allowed. Mehta contended that rapid unregulated constructions were being carried out by sim ply taking clearances from village panchayats, which are not expert bodies. He added that due to such unregulated constructions, pollutants were discharged in the Ganga and the hills have become vulnerable to landslides and earthquake. Green activists in the state, however, were a tad sceptical, saying various such orders were passed earlier too but there was lack of po itical will to implement them. Environmentalist Ravi Chopra said, “After the 2013 deluge, then CM Vijay Bahuguna had also ordered against construction within 200 metres of Ganga banks. Var ious court orders, too, had been issued. But till date, no efforts have been made to implement them. This order might meet the same fate.“

List of municipalities / Urban Local Bodies in the Ganga River Basin

From Haridwar to Diamond Harbour

This is a list of all urban areas that occur along the Ganga. They have been listed in the order in which they occur from Haridwar to Diamond Harbour. (The second or third name in each line is the precise town)

1 Haridwar Haridwar (including NPP + BHEL Ranipur) OG + ITS

2 Dehradun Rishikesh NPP

3 Chamoli Gopeshwar NPP

4 T ehri Garhwal T ehri (T apovan - Rishikesh) NPP

5 Garhwal Srinagar NPP

6 Chamoli Joshimath NPP

7 Uttarkashi Uttarkashi (Budkot) NPP

8 T ehri Garhwal Muni ki Reti - Dhaluwala NP + CT

9 Chamoli Gaucher NP

10 Chamoli Karnaprayag NP

11 Rudraprayag Rudraprayag NPP

12 Chamoli Kirtinagar NP

13 Chamoli Nandprayag NP

14 Chamoli Badrinath(puri) NP

15 T ehri Garhwal Devprayag NP

16 Allahabad Allahabad M Corp. + OG + CB

17 Farrukhabad Farrukkabad NPP

18 Ghazipur Ghazipur NPP + OG

19 Kanpur Nagar Kanpur M Corp. + OG + CB

20 Mirzapur Mirzapur NPP

21 V aranasi V aranasi M Corp.

22 Chandauli Mughal Sarai NPP

23 Moradabad Moradabad (Ramganga) M Corp

24 Ballia Ballia NPP

25 Unnao Unnao NPP

26 Fatehpur Fatehpur NPP

27 Bijnor Bijnor NPP

28 Kannauj Kannauj NPP

29 Unnao Gangaghat NPP S.No. State District T own T ype

30 Bijnor Najibabad NPP

31 Jyotiba Phule Nagar Gajraula NP

32 Bijnor Nagina NPP

33 Bijnor Chandpur NPP

34 Bijnor Dhampur NPP

35 Bulandshahar Jahangirabad NPP

36 Sant Ravidas Nagar Bhadohi NPP

37 Bulandshahr Anupshahar NPP

38 Mirzapur Chunar NPP

39 Ghazipur Saidpur NP

40 Ghaziabad Garhmukhteshwar NPP

41 V aranasi Ramnagar NPP

42 Bulandshahar Narora NP

43 Kanshiram Nagar Soron NPP

44 Meerut Hastinapur NP

45 Kanpur Nagar Bithoor NP

46 Budaun Babrala NP

47 Bhojpur Arrah M Corp.

48 Bhagalpur Bhagalpur M Corp.

49 Buxar Buxar NP

50 Saran Chapra NP

51 V aishali Hajipur NP

52 Munger Munger M Corp.

53 Patna Patna M Corp. + OG

54 Patna Danapur (Dinapur Nizamat) NP + CB

55 Begusarai Begusarai M Corp

56 Katihar Katihar M. Corp + OG

57 Munger Jamalpur NP

58 Nalanda Bihar Sharif M. Corp

59 Patna Mokameh NP

60 Patna Fatuah NP

61 Patna Barh NP S.No. State District T own T ype

62 Begusarai Barauni NP

63 Bhagalpur Sultanganj NP

64 Buxar Dumraon NP

65 Kaimur (Bhabua) Bhabua NP

66 Lakhisarai Lakhisarai NP

67 Patna Phulwari Sharif NP

68 Lakhisarai Barahiya NP

69 Bhagalpur Kahelgaon (Colgong) NP + CT

70 Patna Bakhtiyarpur NP

71 Bhagalpur Naugachhia NP

72 Saran Sonepur NP

73 Sahebganj Sahebganj NP

74 Sahebganj Rajmahal NP

75 Kolkata Kolkata M Corp.

76 Maldah English Bazaar M

77 Murshidabad Bahrampur M

78 Nadia Santipur M

79 Purba Medinipur Haldia M

80 Uttar Dinajpur Raiganj M

81 Nadia Krishnanagar M

82 Nadia Nabadwip M

83 North 24 Parganas Barrackpore M

84 Hugli Uttarpara Kotrung M

85 Hugli Rishra M

86 Hugli Baidyabati M

87 Hugli Champdani M

88 Hugli Bhadreshwar M

89 North 24 Parganas Kamarhati M

90 North 24 Parganas Baranagar M

91 North 24 Parganas Naihati M

92 North 24 Parganas Kanchrapara M + OG

93 Hugli Serampore M S.No. State District T own T ype

94 Hugli Hugli-Chinsurah M + OG

95 South 24 Parganas Maheshtala M

96 North 24 Parganas Panihati M

97 Haora Bally M

98 Haora Ulluberia M + OG

99 North 24 Parganas Khardah M

100 Haora Howrah M Corp

101 Hugli Bansberia M

102 Hugli Chandannagar M Corp

103 North 24 Parganas T itagarh M

104 North 24 Parganas Halishahar M

105 Nadia Kalyani M

106 North 24 Parganas Bhatpara M + OG

107 Murshidabad Dhulian M

108 Murshidabad Jangipur M

109 Nadia Ranaghat M

110 Murshidabad Jiaganj-Azimganj M

111 Barddhaman Katwa M

112 Nadia Chakdah M

113 Hugli Konnagar M

114 South 24 Parganas BudgeBudge M

115 Nadia Gayespur M

116 North 24 Parganas Garulia M

117 Murshidabad Murshidabad M

118 South 24 Parganas Diamond Harbour M

Abbrevations Used:

CB - Cantonment Board/Cantonment,

M – Municipality ,

NPP- Nagar Palika Parishad,

M. Corp - Municipal Corporation/Corporation,

NP - Nagar Panchayat,

CT - Census Town,

OG - Out Growth,

ITS- Industrial Township

List of villages on the Ganga...

...in Bihar

Bihar

The following is a complete list of all important villages (i.e. village councils) in Bihar along the banks of River Ganga.

|

State |

District |

Block |

Gram panchayat (Village council) |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Bachhwara |

Bisanpur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Bachhwara |

Chamatha-I |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Bachhwara |

Chamatha-II |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Bachhwara |

Chamatha-III |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Bachhwara |

Dadpur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Bachhwara |

Rani-III |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Ballia |

Bhawanand Pur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Ballia |

Parmanand Pur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Barauni |

Amarpur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Barauni |

Malhipur (South) |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Barauni |

Simaria-II |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Matihani |

Balahpur -I |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Matihani |

Khorampur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Matihani |

Ramdiri -III |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Matihani |

Ramdiri-2 |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Matihani |

Shihma |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Sahebpur Kamal |

Raghunathpur Barari |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Sahebpur Kamal |

Samastipur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Sahebpur Kamal |

Sandalpur |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Samho Akha Kurha |

Akbar Pur Barari |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Teghra |

Nipania |

|

Bihar |

Begusarai |

Teghra |

Ratgaon |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Bihpur |

Bihpur South |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Bihpur |

Lattipur South |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Antichak |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Bholsar |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Birbanna |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Ekdara |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Kisundas Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Mohanpur Goghatta |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Pakki Sarai |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Colgong |

Shyam Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Gopalpur |

Abhia Pachagachia |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Gopalpur |

Babu Tola Kamlakund |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Gopalpur |

Gopalpur Dimha Gopalpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Gopalpur |

Saidpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Gopalpur |

Tintanga Karari |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Ismailpur |

Ismailpur Paschimi Bhitha |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Ismailpur |

Ismailpur Purabi Bhitha |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Ismailpur |

Narayanpur Laxmipur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Ismailpur |

Parbatta |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Kharik |

Akidatpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Kharik |

Khairpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Kharik |

Raghopur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Narayanpur |

Baikatpur Dudhaila |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Narayanpur |

Jaypurchuhar East |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Narayanpur |

Shahzadpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Narayanpur |

Sihpur East |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Narayanpur |

Sihpur West |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Nathnagar |

Gosaidas Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Nathnagar |

Rattipur Bariya |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Nathnagar |

Shanker Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Babupur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Bakharpur East |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Bakhrpur West |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Ekchari Diyara |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Gobindpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Khavaspur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Manik Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Mohanpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Parsu Rampur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Pirpainti |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Pirpainti |

Rani Diara |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Rangrachowk |

Tintanga Diyara North |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sabour |

Barari |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sabour |

Farka |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sabour |

Khankita |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sabour |

Mamalkha |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sabour |

Rajandipur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sabour |

Shankarpur Diyara |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Abzuganj |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Akabar Nagar |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

E. Chicharaun |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Gangania |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Kamarganj |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Kishanpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Masdi |

|

Bihar |

Bhagalpur |

Sultanganj |

Tilakpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Ara |

Ijari |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Ara |

Sundarpur Barja |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Akauna |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Babura West |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Balua |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Barhara |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Khawas Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Nargada |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Nathmal Pur |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Nekham Tola |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Semaria Pararia |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Sinha |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Barhara |

Sohra |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Shahpur |

Damodarpur |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Shahpur |

Gaura |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Shahpur |

Jhaua Belbahiya |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Shahpur |

Lachatola Bersingha |

|

Bihar |

Bhojpur |

Shahpur |

Lalu Ka Dera |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Brahmpur |

North Nainijor |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Brahmpur |

South Nainijor |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Buxar |

Ahirauli |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Buxar |

Jaso |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Buxar |

Kamarpur |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Buxar |

Khutahan |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Buxar |

Umarpur |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Chakki |

Jawahi Diar |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Chausa |

Banarpur |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Chausa |

Chausa |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Balihar |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Gangauli |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Keshopur |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Niyazipur |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Rajapur |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Rajpur Kalan |

|

Bihar |

Buxar |

Simri |

Rajpur Kalan Parsanpah |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

Bhawanipur Khatti |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

Choukiya Paharpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

Durgapur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

Kishanpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

North Karimullapur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

Pardiara |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Amdabad |

South Karimullapur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Baisa Govindpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Bakia Sukhay |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Dakshini Bhandartal |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Gurumela |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Kant Nagar |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Mohana Chandpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Purbi Bari Nagar |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Sisia |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Uttari Bhandartal |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Barari |

Vishanpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Kursela |

East Muradpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Kursela |

Jarlahi |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Kursela |

Shahpur Dharmi |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Kursela |

South Muradpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Manihari |

Baghar |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Manihari |

Baghmara |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Manihari |

Dakshini Kantakosh |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Manihari |

Dhuriyahi |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Manihari |

Dilarpur |

|

Bihar |

Katihar |

Manihari |

Uttari Kantakosh |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Banni |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Borna |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Gogri |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Itahari |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Jhiktiya |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Rampur |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Gogri |

Samaspur |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Khagaria |

Rahimpur Dakshin |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Khagaria |

Rahimpur Madhya |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Khagaria |

Rahimpur Uttar |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Bharso |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Dariyapur Bhelwa |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Jarawarpur |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Kabela |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Kulharia |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Lagar |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Madhowpur |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Saurh North |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Saurh South |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Siadatpur Aguani |

|

Bihar |

Khagaria |

Parbatta |

Temtha Karari |

|

Bihar |

Lakhisarai |

Barahiya |

Jaitpur |

|

Bihar |

Lakhisarai |

Barahiya |

Khutaha East |

|

Bihar |

Lakhisarai |

Barahiya |

Khutaha West |

|

Bihar |

Lakhisarai |

Pipariya |

Olipur |

|

Bihar |

Lakhisarai |

Pipariya |

Pipariya |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Bariyarpur (North) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Bariyarpur(South) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Binda Diyara (Jhoua Bahiyar) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Binda Diyara(Harinmar) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Binda Diyara(Kalyan Tola) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Karhariya (East) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Karhariya (West) |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Nirpur |

|

Bihar |

Munger |

Bariyarpur |

Pariya |

|