Ayodhya (Babri Masjid/ Ram Janambhoomi): the dispute

(→1994-2019: Four failed mediation attempts) |

(→The legal case: 1885- 2017) |

||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

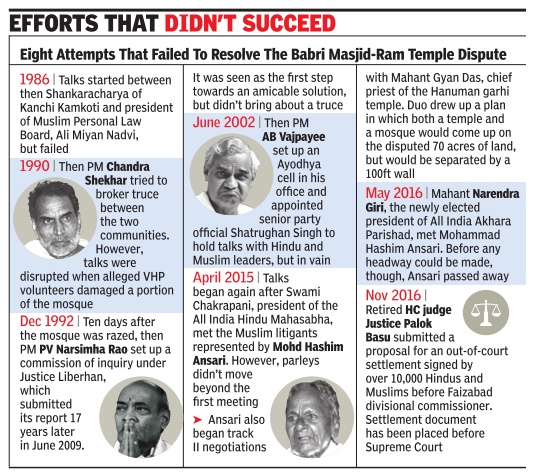

“Ayodhya is a storm that will pass”, the Supreme Court had hoped. It had been proved wrong. An amicable solution eludes the vexed issue. BMAC-VHP negotiations had reached a critical stage in the late 1980s before breaking down. Two years ago, then CJI J S Khehar had surprised many by offering to be the facilitator for a dialogue between the leaders of the two communities warring over the disputed land. But, little came out of it. The storm continues to threaten the communal harmony. It is doubtful whether the final judgment from the highest court would be able to tame the storm. | “Ayodhya is a storm that will pass”, the Supreme Court had hoped. It had been proved wrong. An amicable solution eludes the vexed issue. BMAC-VHP negotiations had reached a critical stage in the late 1980s before breaking down. Two years ago, then CJI J S Khehar had surprised many by offering to be the facilitator for a dialogue between the leaders of the two communities warring over the disputed land. But, little came out of it. The storm continues to threaten the communal harmony. It is doubtful whether the final judgment from the highest court would be able to tame the storm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==1949== | ||

| + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/how-ram-lalla-idol-appeared-inside-the-babri-masjid-in-1949/articleshow/91644130.cms Krishna Jha & Dhirendra K Jha, May 19, 2022: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 11 pm, December 22, 1949. Moments before Abhiram Das stood at the threshold of the temple at Ramghat, Ayodhya slept in peace. Although it was barely eleven in the night, the township, located at the edge of Faizabad, had passed into deep slumber. | ||

| + |

The night was cold, and a layer of still air covered Ayodhya like a blanket. Feeble strains of Ramakatha wafted in from the Ramachabutara. Perhaps the devotees keeping the story of Lord Rama alive were getting tired and sleepy. The sweet murmur of the Sarayu added to the deceptive calm.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | The temple at Ramghat on the northern edge of Ayodhya was not very old. The initiative to erect it had been taken just a decade ago. But the enthusiasm did not appear to have persisted, and the construction had been halted halfway. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The structure remained small in size and the absence of the desperately required final touches made it look crude but for the grand, projecting front facade and the rooms on both sides of the garbhagriha. In the backyard was a mango grove, unkempt, untended. About a kilometre away, River Sarayu, the lifeline of Ayodhya, flowed along with sandy stretches on both sides of its shoreline. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Abhiram Das stumbled as he climbed the half-built brick steps, lost in the shadows of the dimly lit lamp hanging on the wall, but recovered and entered the side room of the temple. The Ramghat temple was the prized possession of Abhiram Das, who himself lived a kilometre away in a one-room tenement that formed part of the complex of Hanumangarhi, a fortress-like structure in the heart of Ayodhya. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Within the precincts of its imposing walls, there was an old, magnificent temple dedicated to Lord Hanuman. The circular bastions on each of the four corners of Hanumangarhi enhanced its structural elegance and artistic grandeur. Around the fortress and as part of the complex, there were rooms for sadhus, a Sanskrit pathshala and a huge, narrow stretch, where there was a gaushala, beside which Abhiram Das lived, close to the singhdwar of Hanumangarhi. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

That, however, was only a night shelter for him. In his waking hours, Abhiram Das had innumerable engagements, and the temple at Ramghat always figured prominently among them. Not just because it was under his control, but because it housed his three younger brothers and four cousins, most of whom were enrolled with the Sanskrit pathshala in Hanumangarhi. Two of his cousins, Yugal Kishore Jha and Indushekhar Jha, as well as Abhiram’s younger brother, Upendranath Mishra, were students of Maharaja Intermediate College in Ayodhya. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Abhiram Das’s relatives lived in the rooms adjacent to the garbhagriha and survived on offerings made by devotees to Lord Rama. They cooked for Abhiram as well. Thrice a day, they would carry his food to his room, braving the scorching sun in summer, icy winds in winter, and downpours during the rainy season. Abhiram’s closeness to his extended family was unexpected in a sadhu. The ascetic in him often cautioned against such human weaknesses, but it had always been beyond him to transcend them. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Yet, visiting Ramghat temple that night was not part of his original plan as he set out to install the idol of Lord Rama inside the sixteenth-century mosque. Nor were his brothers and cousins used to seeing him at this odd hour in his second home. For, like any other sadhu, he was in the habit of going to bed and getting up early. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Indeed, it was awkward for Abhiram Das too. He had to change his original plan owing to the sudden disappearance of his friend Ramchandra Das Paramhans, who was supposed to accompany him in his surreptitious mission. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to the plan, Paramhans was to arrive at the Hanumangarhi residence of Abhiram Das by 9 pm, after his meal. They were to go together to the Babri Masjid, where another sadhu, Vrindavan Das, was to join them with an idol of Lord Rama.

The trio was then supposed to go inside the sixteenth-century mosque, plant the idol below its central dome and keep the deserted place of worship under their control till the next morning when a larger band of Hindu communalists would pour in for support. They had been strictly instructed that their entry into the mosque had to be completed at any cost before midnight — the time when there would be a change of guard at the gate of the mosque. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Every detail had been planned meticulously, and everything seemed to be moving accordingly, till Ramchandra Das Paramhans vanished from the scene. Forty-two years later, when none of those involved in planting the idol was alive to contradict him, Paramhans sought to appropriate history. “I am the very man who put the idol inside the masjid,” Paramhans declared in a news report that appeared in the New York Times on December 22, 1991. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

However, on that fateful night of 1949 and for a few days thereafter, Paramhans went missing from the scene in Ayodhya. Indushekhar Jha who, together with Yugal Kishore Jha, followed Abhiram Das into the mosque, had this to say about Paramhans: “I saw Paramhans in the evening [of December 22, 1949]. Thereafter, he was not seen in Ayodhya for [the] next three days. Yet it was he who took maximum advantage from that incident…” | ||

| + | |||

| + | …As for the reason for his sudden decision to leave Ayodhya and participate in the conference instead of accompanying Abhiram Das, nothing can be said for sure except that he may have been apprehensive of the consequences of the act. On his part, Ramchandra Das Paramhans, after having taken credit in 1991 for installing the idol inside the Babri Masjid, preferred to remain silent on the issue till his death in 2003. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Back in those uncertain moments of 1949, Abhiram Das waited at his Hanumangarhi residence for Ramchandra Das Paramhans till around 10 pm, after which he left in search of his friend. Paramhans lived in a temple in the Ramghat locality of Ayodhya. It was quite close to the one inhabited by Abhiram Das’s brothers and cousins. But Paramhans was not to be found there. | ||

| + |

This made Abhiram rather less confident of accomplishing the task he had set out for. The strength he had was that of faith, without any rationale to go with it. But as the moment approached, the magnitude of the job, as well as its possible repercussions unfolded with a clarity that was missing till then.

Wanting to prepare for any eventuality, he decided to give appropriate instructions to his brothers and cousins at the temple in Ramghat before proceeding on his journey towards the Babri Masjid. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With so much force did Abhiram Das enter the room that his cousin Awadh Kishore Jha felt that it was some wild animal blundering inside… While the occupants of the room were getting out of bed, Abhiram Das kept pacing up and down, quivering — apparently with the strength of the emotions stirring within him. In one hand, he held the long bamboo staff, while the other instinctively fumbled with the beads in the mala-jhola. | ||

| + |

As they got up, he asked his younger brother Upendranath Mishra to hold the hand of Yugal Kishore Jha, the eldest of his cousins there, and said, “Listen to me carefully. I am going and may never return. If something happens to me, if I don’t return till morning, Yugal will be my successor and in charge of this temple.” Yugal Kishore Jha pulled his hand back and stared at him incredulously. “What on earth are you up to, maharaj?”

| ||

| + | But Abhiram Das said nothing, nor did he look at anyone. Having put the succession issue in order, he was ready to resume his mission. He rushed out of the room and then the temple, and with rapid strides, dissolved into the darkness. His cousins Yugal Kishore Jha and Indushekhar Jha followed him, completely clueless about what was happening. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It took them hardly ten minutes to reach the spot. As they approached the open area near the Ramachabutara, another vairagi emerged from the dark corner of the outer courtyard of the Babri Masjid. It was Vrindavan Das, a Ramanandi vairagi of the Nirvani Akhara, who lived in a thatched hut near the gate of the sixteenth-century mosque. A heavy cotton bag hung from his shoulder, and there was a small idol of Rama Lalla in his hands.

Abhiram Das took the idol from Vrindavan Das and grasping it with both his hands, walked past him — as if he were not there — towards the wall that separated the inner courtyard around the Babri Masjid from the outer courtyard that contained the Ramachabutara. Vrindavan Das tried to ask him something in whispers, but Abhiram Das, appearing calmer now, once again took no notice of him.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | Abhiram Das stood at the end of the pathway close to the inner courtyard, staring at the walls — his sole hurdle. Then, apparently addressing Vrindavan Das, he said, “Maharaj …”

| ||

| + | Vrindavan Das said nothing, just moved closer to him, eager not to miss any word of instruction that might come his way. | ||

| + |

“Maharaj,” said Abhiram Das again, this time coaxingly. He turned his head to look at him and said, “Follow me.” With these words, he held the idol firmly and began climbing the wall. Soon, he was straddling it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Excerpted with permission from Ayodhya: The Dark Night ‒ The Secret History of Rama’s Appearance in Babri Masjid (published by HarperCollins India) | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Crime|B AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAM | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|B AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAM | ||

| + | ]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBHOOMI)AYODHYA (BABRI MASJID/ RAM JANAMBH | ||

| + | ]] | ||

==1949-1991== | ==1949-1991== | ||

Revision as of 01:24, 20 June 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

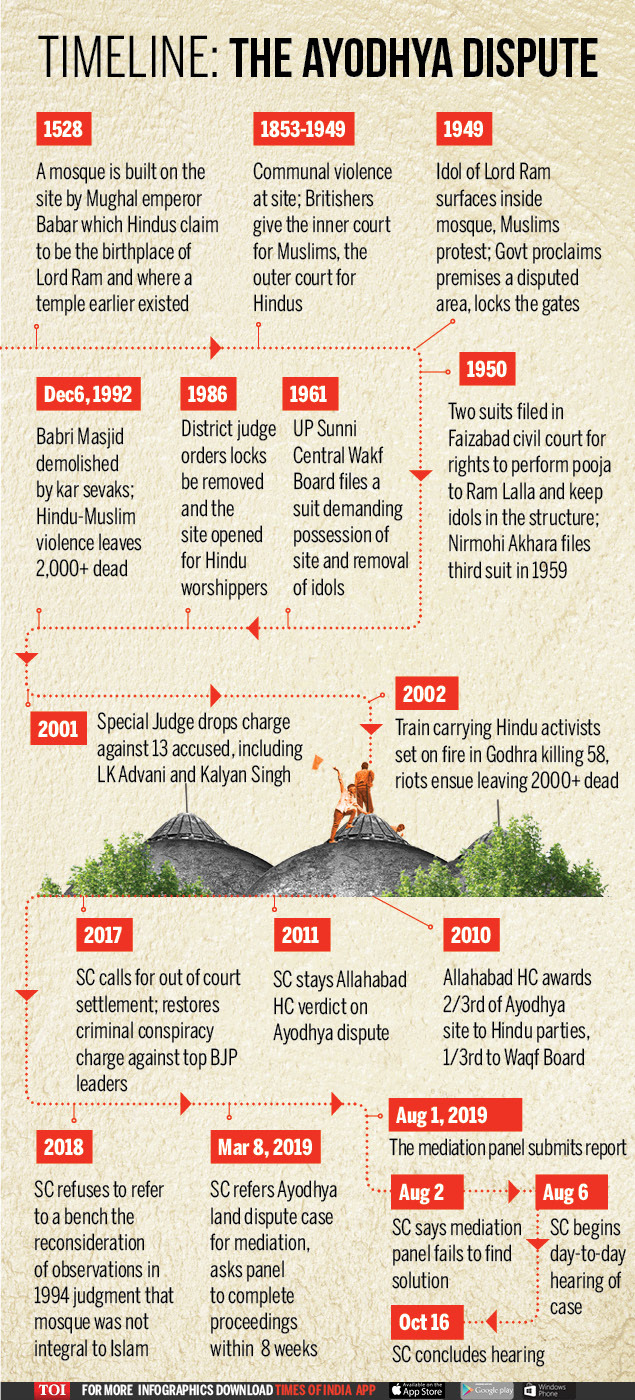

A timeline

The authors of this page are

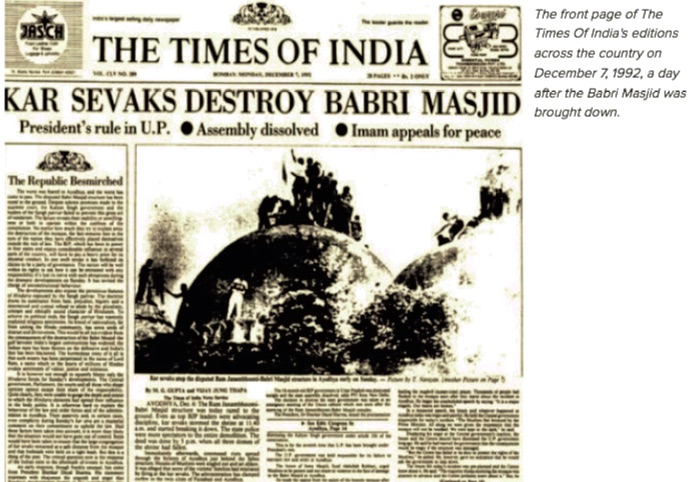

Babri Masjid demolition: Timeline of events and aftermath | By Mid-day online correspondent | 06-Dec-2016 |Mid-day, which is almost identical to:

Timeline: Ayodhya holy site crisis 6 December 2012 | BBC

Haider Abbas | Babri Masjid: The story of crime # 197/1992| The Milli Gazette 16-30 June 2012

With additional inputs from Q&A: The Ayodhya dispute |5 December 2012| BBC

From: Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

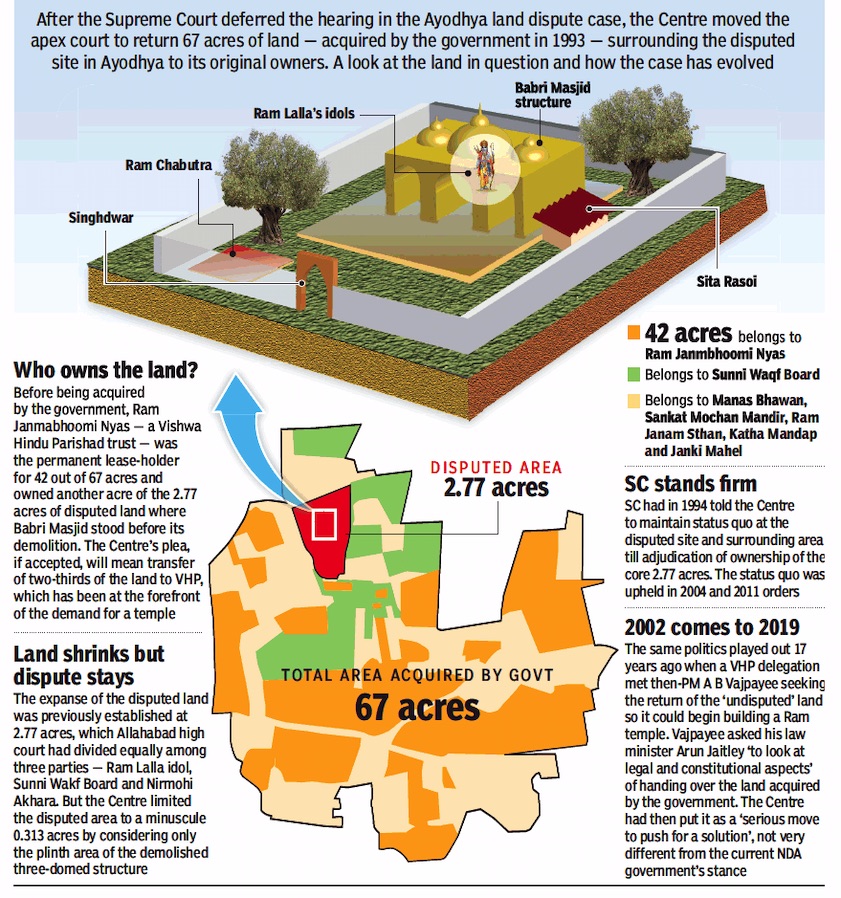

See graphic:

Map of structure as it stood before demolition

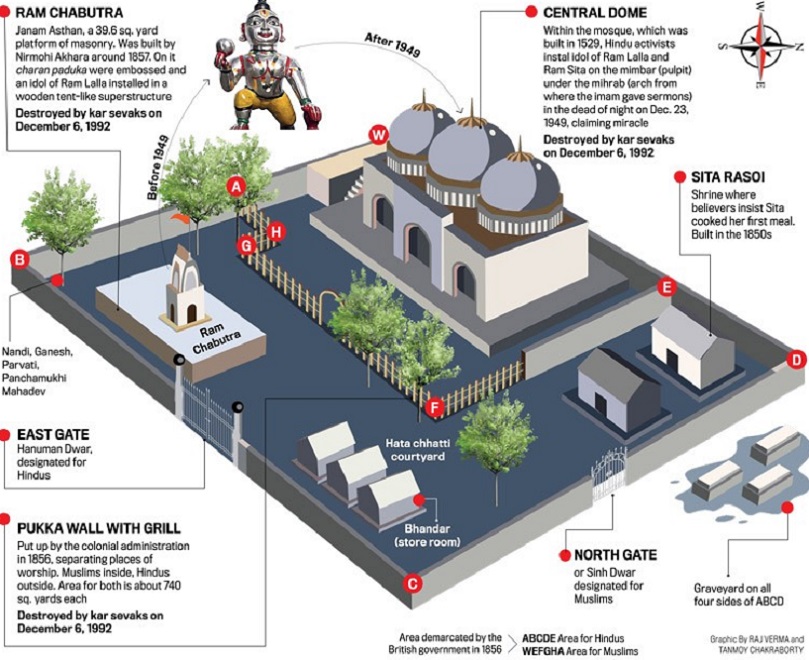

Summary: Accounts of Europeans suggest both worshipped pre-1857

Vaibhav Purandare, Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: Vaibhav Purandare, Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

PCarnegy is not a name that will ring a bell in contemporary India. But this Britisher, an assistant commissioner of the Raj in Faizabad in the 1860s, is among those who played, unwittingly, a key role in providing champions of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement substantive material to make the case that Hindus had launched their struggle for the ‘janmasthan’ in Ayodhya much before the Ram Lalla idol was installed in 1949.

Writing a historical sketch of ‘Fyzabad’, as he spelt it, Carnegy wrote that until 1855, the year in which communal violence broke out in Ayodhya over possession of Hanuman Garhi and the ‘janmasthan’, “Hindus and Muslims alike used to worship in the mosque-temple.” But “since British rule (in 1858, that is) a railing has been put up to prevent disputes, within which in the mosque the Mahomedans pray, while outside the fence the Hindus have raised a platform on which they make their offerings.”

Carnegy wasn’t the first to point to “joint worship” in the inner yard. That credit goes to Austrian Jesuit priest Joseph Tieffenthaler who visited Awadh circa 1770 and recorded that 12 “koti and kasauti” pillars supported the Babri Masjid’s interior arcades and that there stood a square box called the “bedi” or cradle at the entrance, “where Vishnu took incarnation as Ram”. Tieffenthaler’s theory was that it wasn’t Babar or Mir Baqi in 1528 but Aurangzeb in the 17th century who had destroyed the shrine “to deprive Hindus of their faith”. Yet, the Jesuit priest wrote, Hindus still came to the spot to do their circumambulation and prostrated.

The first to refer to an inscription inside the masjid which stated it was built in 1528 by Babar’s chieftain Mir Baqi was F C Buchanan, physician of Lord Wellesley, who visited Ayodhya between 1807 and 1814. And the first legal record came in 1822, when a superintendent in Faizabad court, Hafizullah, submitted his report in Persian saying “the mosque founded by emperor Babur is situated at the Janmasthana”, “adjacent to the kitchen of Sita”.

After that, records about the dispute and about the persistent Hindu claim to the disputed site piled up quickly, with other European travellers following in Tieffenthaler’s footsteps and British officials such as A F Millet taking the path trodden by Carnegy.

Millet, a land revenue officer of Faizabad district, stated in his report of 1880 that Hindus and Muslims had worshipped “alike” inside the structure, and the writer-traveller Edward B Eastwick recorded in his ‘Handbook of the Bengal Presidency’ in 1888 that before 1858, namaz and puja were both performed inside the shrine.

The British officials of the period demonstrated the opposite of the well-known Indian disregard for documentation. The gazetteers of 1854, 1881, 1892, 1905, the Archaeological Survey Report of 1891 and later archaeological and general survey reports of the 1930s reinforced the theory of the mosque having been constructed after demolishing a temple and of intermittent Hindu efforts to get the spot back. The archaeological report of 1891 by A Fuhrer, who translated three inscriptions inside the mosque, corroborated Buchanan’s view that it was Mir Baqi who “by the order of Babar” had built the mosque circa 1520 “on the very spot where the old temple Janmasthanam of Ramchandra was standing”. The old temple, Fuhrer said, “must have been a very fine one, for many of its columns have been used by the Musalmans in the construction of Babar’s masjid”.

A police complaint launched by the muezzin of the Babri Masjid in November 1858 too became part of the ‘janmabhoomi’ docket for the protemple side. Syed Muhammad Khatib, who used to call the faithful to prayer in the mosque, had written to local cops a year after the 1857 revolt that a Nihang Sikh, a Bairagi (ascetic), was “on the rampage at the Janmasthan.” He had forcibly built a “chabutra in the middle of the Babri mosque” and had raised the platform and placed a flag, a picture and an idol, the muezzin complained, urging authorities to get the construction demolished and oust Hindus from the place, where, earlier, the “nishaan of Janmasthan lay for hundreds of years and Hindus used to do puja.”

These documents were put forward by the Hindu side in the post-1985 VHP (and later BJP) agitation phase to buttress their case.

The Janam Sakhis of Guru Nanak Dev

Abhinav Garg, Nov 11, 2019: The Times of India

The SC verdict that settled the Ayodhya dispute has a historical nugget tucked away in its 1,045 pages that many might not have known about — the Sikh connection in what has been seen as a Hindu-Muslim tussle.

An evidence that helped strengthen the Hindu side’s claim to the disputed site was the visit by Guru Nanak Dev to Ayodhya for Ram Janmabhoomi darshan in 1510-11 AD. Babri Masjiddid not come up until after the 1526 Battle of Panipat.

More than three centuries later, in 1857, a Nihang Sikh barged inside the mosque and occupied it for a considerable amount of time, even setting up a platform on which an idol of Lord Ram was placed. With a posse of 25 Sikhs standing guard outside, the Nihang Sikh lit a fire and started arrangements for puja, leading to the first recorded instance of friction between Hindus and Muslims over the structure. The Nihang Sikh scrawled “Ram” on the walls of the mosque, according to police complaint.

The addenda to verdict bring on record the Janam Sakhis, or writings that profess to be biographies of Guru Nanak Dev. On the question of “whether the disputed structure is the birthplace of Lord Ram according to belief of Hindu devotees”, the SC says there is no material to identify the exact place of Ram Janmabhoomi. But it recognises the visit of Guru Nanak Dev to Ayodhya as an event depicting visits by pilgrims even before 1528 AD.

The judgment says, “It is found that in period prior to 1528 AD, there were sufficient religious texts, which led Hindus to believe the present site of Ram Janmabhoomi as birthplace of Lord Ram.”

One of the witnesses in suit number 4, during his examination in Allahabad HC, had referred to books on Sikh cult and history. He said Guru Nanak Dev had sought darshan at the Shri Ram Janmabhoomi temple. To his statement, he appended various Janam Sakhis documenting the visit of Guru Nanak Dev to Ayodhya.

The verdict also traces a second event that occurred against the backdrop of 1857 transfer of power, when complaints sent to the Oudh administration (as Ayodhya and nearby areas were then referred to) reported the presence of Sikhs. A complaint in 1860 to deputy commissioner of Oudh said local Muslims were facing problems in performing namaz at the mosque. “The Azaan of Moazzin was met with the blowing of conch shells by Hindus. A contentious situation was arising. The Nihang Sikh was evicted from the site and a record was maintained,” SC notes, deducing that it showed namaz was at that stage being performed in the mosque.

That incident led to the installation of a railing in the form of a grill-brick wall outside the mosque. It was also the genesis of division of the complex into an inner courtyard (in which stood the structure of the mosque) and outer courtyard. “The construction of a railing in 1856-7 to provide a measure of separation between the inner and outer courtyards led to the construction of a platform by Hindus in close proximity to railing in outer courtyard. The platform, called Ramchabutra, became a place of worship for Hindus,” states the verdict.

History: 1527- 1992

1527-1885

The Indian city of Ayodhya, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, is located 550 km east of New Delhi. The name Ayodhya means, “Not to be warred against,” [Or ‘The land without war’] (Reality Views)

The destruction of the 16th-century mosque in the town of Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh was a break-point in the Hindu-Muslim fabric of the nation. While some say that the site where the mosque stood is the birthplace of Lord Ram, the issue has been raging from eons. Here is a timeline of how communalism threw modern India into jeopardy.

1527 or 1528: A mosque is built on the site which some Hindus say marks the spot where Lord Ram was born. Some have claimed an old Hindu temple was demolished and a mosque constructed at the same place in Ayodhya and named after Babur and hence the name Babri Masjid.

According to Reality Views The date of the construction of the Babri Mosque is disputed. Before the 1940s, the Mosque was called "Masjid-i Janmasthan".

1853: First recorded incidents of communal clashes at the site.

1859: British colonial administration erected a fence to separate the places of worship, allowing the inner court to be used by Muslims and the outer court by Hindus. This stood for 90 years.

1855: Hindus and Muslims clash over possession of the mosque. There are claims that Sita Rasoi and Ram Chabootara were built around this time (Reality Views)

1885: Mahant Raghubar Das files a suit seeking permission to build a canopy on Ram Chabootra (Reality Views)

The legal case: 1885- 2017

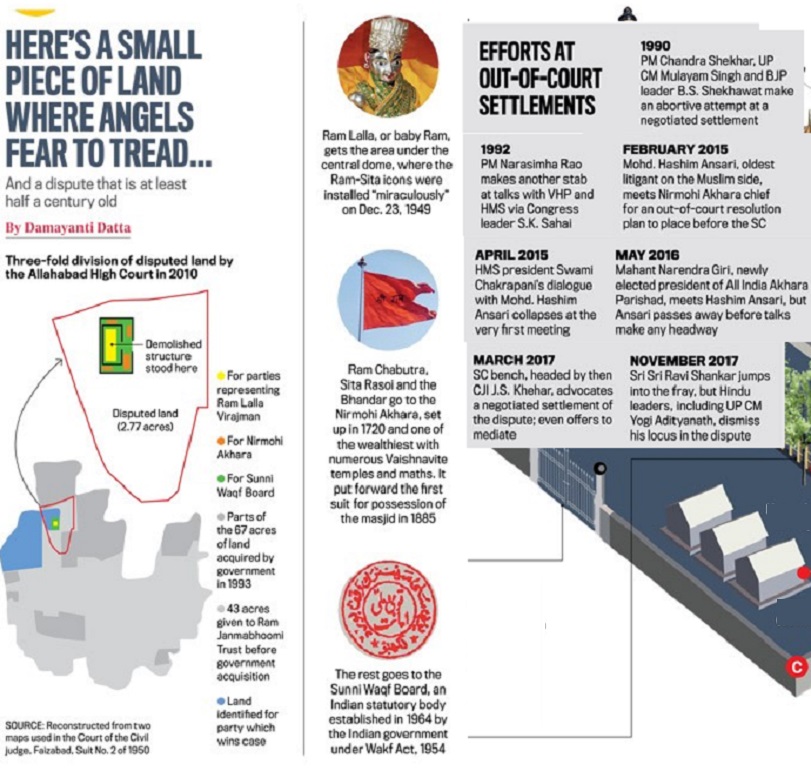

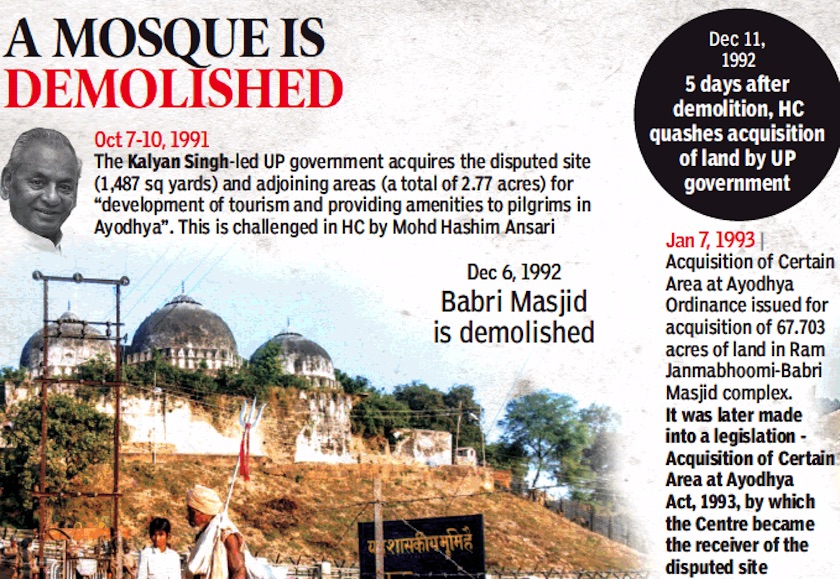

The juggernaut of litigation for ownership over 2.77 acres of Ayodhya land, where the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmabhoomi disputed structure stood since 1528 till its demolition on December 6, 1992, is about to start rolling towards final destination in the Supreme Court.

But the question that stares the two communities — Hindus and Muslims — is whether the final adjudication on the title suits by the highest court of the land be able to bury the ‘more than century’ old dispute and bring peace between the communities? History has witnessed large-scale rioting and loss of lives because of polarisation over the issue in the last three decades.

Advocate Virag Gupta has published a compendium on Ayodhya case in courts giving insight to the birth of a small stream of litigation on Ayodhya land and how it grew into a big river over nearly two centuries. The strong undercurrents against the mosque was felt by the British in the 1850s and they fenced the structure in 1859.

In 1885, a suit seeking permission for constructing a Ram Temple at the disputed site was filed by Mahant Raghubar Das. The trial court rejected it fearing such permission could lead to riots. Appeals too were rejected. In 1934, a mob damaged parts of the disputed structure. The British repaired it. Muslims continued to offer prayer and Hindus worshipped at Ram-Chabutra and Kaushalya Rasoi.

On the intervening night of December 22-23, 1949, idol of Lord Ram was surreptitiously placed under the central dome of the disputed structure. Worship by devotees started in a big way from next morning. District authorities, fearing riots, sealed the premises immediately.

In 1950, two civil suits were filed — one by G S Visharad of Hindu Mahasabha claiming right to worship and second by Paramhans Ramachandra Das seeking to restrain administration from removing the idols. The trial court allowed worship and restrained the district authorities from removing the idols. The Allahabad high court confirmed the trial court’s interim orders in 1955.

In 1959, Nirmohi Akhara filed the third suit seeking right to worship idols under

the central dome and handing over of management of the disputed structure to a Hindu Mahant. Sunni Central Wakf Board filed the fourth suit in 1961 seeking removal of idols and possession of the disputed structure, but withdrew it in 1964. It was added as a defendant in the suit filed by Paramhans Ramchandra Das in 1989.

The White Paper on Ayodhya brought out by the Congress government led by P V Narasimha Rao in February 1993 said: “The Hindu idols thus continued inside the disputed structure since 1949. Worship of these idols by Hindus also continued without interruption since 1949 and the structure was not used by the Muslims for offering prayers since then.”

Another important turn to the roller-coaster journey of Ayodhya dispute took place in 1986, when the Faizabad district court ordered opening of the lock placed on the iron grill gate leading to the central dome of the disputed structure. Many believe the gates were opened at the behest of central government headed by Rajiv Gandhi.

Babri Masjid Action Committee (BMAC) was formed and it launched protest movement seeking restoration of disputed structure to Muslims while Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) spearheaded the Hindu organisations and mobilised public for construction of a Ram temple at the disputed site. The title suits pending in Faizabad district court were transferred to Lucknow bench of Allahabad HC in 1989.

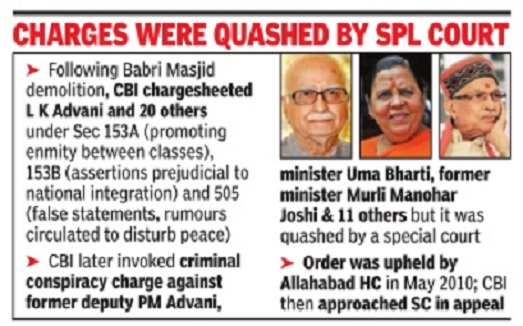

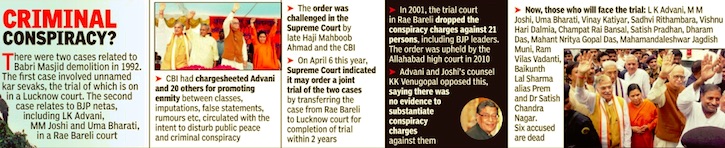

After December 6, 1992 demolition of Babri Masjid, the Ayodhya case got split into two — one, the title suits pending in Allahabad HC’s Lucknow bench and second, the criminal cases filed against top BJP leaders including L K Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi for exhorting the Kar Sevaks to raze down the disputed structure. The central government acquired the disputed structure and land surrounding it through a law in January 1993.

The Allahabad high court (Lucknow) bench of Justices S U Khan, Sudhir Agarwal and D V Sharma had considered archaeological evidence, which conclusively indicated that Babri Masjid was built on the ruins of an ancient Hindu temple. The HC divided the Ayodhya land equally between three parties — Ram Lalla (idol), Nirmohi Akhara and Sunni Wakf Board.

The criminal case against BJP leaders too has entered its final phases with the Supreme Court on April 19, 2017 asking the trial court to proceed with the trial, which had been stalled for a long time, and conclude it within two years. That means, the trial court, if it does not seek extension of the two-year time period, would pronounce its verdict before April 19 this year.

While striking down acquisition of 2.77 acres of disputed Ayodhya land, on which the structure before demolition stood, and surrounding 67.703 acres of land, the SC in Ismail Faruqui case [1994 (6) SCC 360] had asked the Centre to act as Receiver of the two tracts of acquired land till final judgement on the title suits.

In the 1994 judgment, it had said:“We have no doubt that the moderate Hindu has little taste for the tearing down of the place of worship of another to replace it with a temple. It is our fervent hope that the moderate opinion shall find general expression and that communal brotherhood shall bring to the dispute at Ayodhya an amicable solution long before the courts resolve it.”

“Ayodhya is a storm that will pass”, the Supreme Court had hoped. It had been proved wrong. An amicable solution eludes the vexed issue. BMAC-VHP negotiations had reached a critical stage in the late 1980s before breaking down. Two years ago, then CJI J S Khehar had surprised many by offering to be the facilitator for a dialogue between the leaders of the two communities warring over the disputed land. But, little came out of it. The storm continues to threaten the communal harmony. It is doubtful whether the final judgment from the highest court would be able to tame the storm.

1949

Krishna Jha & Dhirendra K Jha, May 19, 2022: The Times of India

11 pm, December 22, 1949. Moments before Abhiram Das stood at the threshold of the temple at Ramghat, Ayodhya slept in peace. Although it was barely eleven in the night, the township, located at the edge of Faizabad, had passed into deep slumber.

The night was cold, and a layer of still air covered Ayodhya like a blanket. Feeble strains of Ramakatha wafted in from the Ramachabutara. Perhaps the devotees keeping the story of Lord Rama alive were getting tired and sleepy. The sweet murmur of the Sarayu added to the deceptive calm.

The temple at Ramghat on the northern edge of Ayodhya was not very old. The initiative to erect it had been taken just a decade ago. But the enthusiasm did not appear to have persisted, and the construction had been halted halfway.

The structure remained small in size and the absence of the desperately required final touches made it look crude but for the grand, projecting front facade and the rooms on both sides of the garbhagriha. In the backyard was a mango grove, unkempt, untended. About a kilometre away, River Sarayu, the lifeline of Ayodhya, flowed along with sandy stretches on both sides of its shoreline.

Abhiram Das stumbled as he climbed the half-built brick steps, lost in the shadows of the dimly lit lamp hanging on the wall, but recovered and entered the side room of the temple. The Ramghat temple was the prized possession of Abhiram Das, who himself lived a kilometre away in a one-room tenement that formed part of the complex of Hanumangarhi, a fortress-like structure in the heart of Ayodhya.

Within the precincts of its imposing walls, there was an old, magnificent temple dedicated to Lord Hanuman. The circular bastions on each of the four corners of Hanumangarhi enhanced its structural elegance and artistic grandeur. Around the fortress and as part of the complex, there were rooms for sadhus, a Sanskrit pathshala and a huge, narrow stretch, where there was a gaushala, beside which Abhiram Das lived, close to the singhdwar of Hanumangarhi.

That, however, was only a night shelter for him. In his waking hours, Abhiram Das had innumerable engagements, and the temple at Ramghat always figured prominently among them. Not just because it was under his control, but because it housed his three younger brothers and four cousins, most of whom were enrolled with the Sanskrit pathshala in Hanumangarhi. Two of his cousins, Yugal Kishore Jha and Indushekhar Jha, as well as Abhiram’s younger brother, Upendranath Mishra, were students of Maharaja Intermediate College in Ayodhya.

Abhiram Das’s relatives lived in the rooms adjacent to the garbhagriha and survived on offerings made by devotees to Lord Rama. They cooked for Abhiram as well. Thrice a day, they would carry his food to his room, braving the scorching sun in summer, icy winds in winter, and downpours during the rainy season. Abhiram’s closeness to his extended family was unexpected in a sadhu. The ascetic in him often cautioned against such human weaknesses, but it had always been beyond him to transcend them.

Yet, visiting Ramghat temple that night was not part of his original plan as he set out to install the idol of Lord Rama inside the sixteenth-century mosque. Nor were his brothers and cousins used to seeing him at this odd hour in his second home. For, like any other sadhu, he was in the habit of going to bed and getting up early.

Indeed, it was awkward for Abhiram Das too. He had to change his original plan owing to the sudden disappearance of his friend Ramchandra Das Paramhans, who was supposed to accompany him in his surreptitious mission.

According to the plan, Paramhans was to arrive at the Hanumangarhi residence of Abhiram Das by 9 pm, after his meal. They were to go together to the Babri Masjid, where another sadhu, Vrindavan Das, was to join them with an idol of Lord Rama. The trio was then supposed to go inside the sixteenth-century mosque, plant the idol below its central dome and keep the deserted place of worship under their control till the next morning when a larger band of Hindu communalists would pour in for support. They had been strictly instructed that their entry into the mosque had to be completed at any cost before midnight — the time when there would be a change of guard at the gate of the mosque.

Every detail had been planned meticulously, and everything seemed to be moving accordingly, till Ramchandra Das Paramhans vanished from the scene. Forty-two years later, when none of those involved in planting the idol was alive to contradict him, Paramhans sought to appropriate history. “I am the very man who put the idol inside the masjid,” Paramhans declared in a news report that appeared in the New York Times on December 22, 1991.

However, on that fateful night of 1949 and for a few days thereafter, Paramhans went missing from the scene in Ayodhya. Indushekhar Jha who, together with Yugal Kishore Jha, followed Abhiram Das into the mosque, had this to say about Paramhans: “I saw Paramhans in the evening [of December 22, 1949]. Thereafter, he was not seen in Ayodhya for [the] next three days. Yet it was he who took maximum advantage from that incident…”

…As for the reason for his sudden decision to leave Ayodhya and participate in the conference instead of accompanying Abhiram Das, nothing can be said for sure except that he may have been apprehensive of the consequences of the act. On his part, Ramchandra Das Paramhans, after having taken credit in 1991 for installing the idol inside the Babri Masjid, preferred to remain silent on the issue till his death in 2003.

Back in those uncertain moments of 1949, Abhiram Das waited at his Hanumangarhi residence for Ramchandra Das Paramhans till around 10 pm, after which he left in search of his friend. Paramhans lived in a temple in the Ramghat locality of Ayodhya. It was quite close to the one inhabited by Abhiram Das’s brothers and cousins. But Paramhans was not to be found there. This made Abhiram rather less confident of accomplishing the task he had set out for. The strength he had was that of faith, without any rationale to go with it. But as the moment approached, the magnitude of the job, as well as its possible repercussions unfolded with a clarity that was missing till then. Wanting to prepare for any eventuality, he decided to give appropriate instructions to his brothers and cousins at the temple in Ramghat before proceeding on his journey towards the Babri Masjid.

With so much force did Abhiram Das enter the room that his cousin Awadh Kishore Jha felt that it was some wild animal blundering inside… While the occupants of the room were getting out of bed, Abhiram Das kept pacing up and down, quivering — apparently with the strength of the emotions stirring within him. In one hand, he held the long bamboo staff, while the other instinctively fumbled with the beads in the mala-jhola. As they got up, he asked his younger brother Upendranath Mishra to hold the hand of Yugal Kishore Jha, the eldest of his cousins there, and said, “Listen to me carefully. I am going and may never return. If something happens to me, if I don’t return till morning, Yugal will be my successor and in charge of this temple.” Yugal Kishore Jha pulled his hand back and stared at him incredulously. “What on earth are you up to, maharaj?” But Abhiram Das said nothing, nor did he look at anyone. Having put the succession issue in order, he was ready to resume his mission. He rushed out of the room and then the temple, and with rapid strides, dissolved into the darkness. His cousins Yugal Kishore Jha and Indushekhar Jha followed him, completely clueless about what was happening.

It took them hardly ten minutes to reach the spot. As they approached the open area near the Ramachabutara, another vairagi emerged from the dark corner of the outer courtyard of the Babri Masjid. It was Vrindavan Das, a Ramanandi vairagi of the Nirvani Akhara, who lived in a thatched hut near the gate of the sixteenth-century mosque. A heavy cotton bag hung from his shoulder, and there was a small idol of Rama Lalla in his hands. Abhiram Das took the idol from Vrindavan Das and grasping it with both his hands, walked past him — as if he were not there — towards the wall that separated the inner courtyard around the Babri Masjid from the outer courtyard that contained the Ramachabutara. Vrindavan Das tried to ask him something in whispers, but Abhiram Das, appearing calmer now, once again took no notice of him.

Abhiram Das stood at the end of the pathway close to the inner courtyard, staring at the walls — his sole hurdle. Then, apparently addressing Vrindavan Das, he said, “Maharaj …” Vrindavan Das said nothing, just moved closer to him, eager not to miss any word of instruction that might come his way. “Maharaj,” said Abhiram Das again, this time coaxingly. He turned his head to look at him and said, “Follow me.” With these words, he held the idol firmly and began climbing the wall. Soon, he was straddling it.

Excerpted with permission from Ayodhya: The Dark Night ‒ The Secret History of Rama’s Appearance in Babri Masjid (published by HarperCollins India)

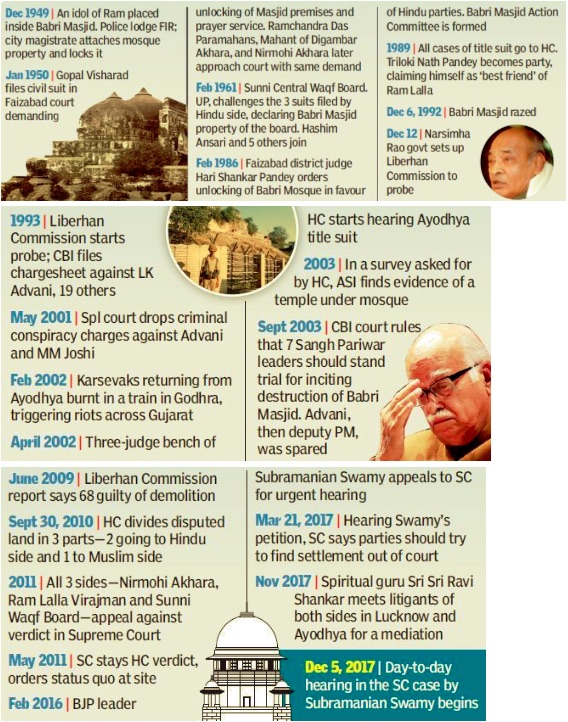

1949-1991

Dec 1949: Idols of Lord Ram appear inside mosque, allegedly placed there by Hindus. Hindu wing is also said to have allegedly said that the idols had miraculously appeared. Muslims protest resulting in both the parties filing civil suits. The government then declared the premises a disputed area and locked the gates. Police lodge FIR; city magistrate attaches mosque property and locks it The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

BBC adds: Muslims say they offered prayers at the mosque until December 1949, when some people placed the idols of Ram under the cover of darkness in the mosque. The worship of the idols began soon after. (End of BBC item)

Jan 1950: Gopal Singh Visharad and Mahant Paramhand Ramchandra Das file civil suits in Faizabad, asking for unlocking of Masjid premises and permission to offer prayers to the idols installed at Asthan Janmabhoomi. Inner courtyard gates are locked, but puja is allowed. (Reality Views) Ramchandra Das Paramahans, Mahant of Digambar Akhara, and Nirmohi Akhara later approach court with same demand The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

1959: Nirmohi Akhara and Mahant Raghunath file a case, claiming to be the sect responsible for conducting puja (Reality Views)

Feb 1961: Sunni Central Waqf Board.UP, challenges the 3 suits filed by Hindu side, declaring Babri Masjid property of the board. Hashim Ansari and 5 others join. Sunni Central Board of Waqfs, UP, claims the mosque and the surrounding land was a graveyard (Reality Views) The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

1984: Hindus form a committee to "liberate" the birth-place of Lord Ram and build a temple in his honour. The movement was spearheaded by Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) to build a temple at the site, which they claimed was the birthplace of Lord Ram. It gathered momentum when they formed a committee to construct a temple at the Ramjanmabhoomi site. Then Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Lal Krishna Advani, took over leadership of campaign.

Feb 1986: Faizabad district judge Hari Shankar Pandey orders unlocking of gates of Babri Mosque after almost five decades in favour of Hindu parties and allowed Hindus to worship inside the 'disputed structure.' The gates were opened in less than an hour after the court decision. Muslims set up Babri Mosque Action Committee in protest against the move to allow Hindu prayers at the site. The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

1989: VHP steps up the campaign and proclaims that a Shilâ or a stone will be established for construction of temple near the area. In November, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad laid foundations of a temple on land adjacent to the 'disputed structure'. (Reality Views) adds: Former VHP vice-president Justice Deoki Nandan Agarwal files a case, seeking the mosque be shifted elsewhere

1989 All cases of title suit go to HC. Triloki Nath Pandey becomes party, claiming himself as ‘best friend’ of Ram Lalla The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

1990: VHP volunteers partially damage the mosque. The then Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar tries to resolve the dispute through negotiations, which fail in 1991.

1991: BJP comes to power in Uttar Pradesh state, where Ayodhya is located. The power at the Centre, is however Congress.

1986: The Babri Masjid Action Committee is formed

Nov 9, 2019: The Times of India

Rs 2,000 from Islamic Scholar, Meeting in Lucknow: How Babri Masjid Action Committee Was Born

As the decades-long legal battle over the Ayodhya land dispute moves towards conclusion, one name that emerges as the biggest crusader for the Muslim cause is that of the committee founded in 1986.

It was a few months after the 1982 Samastipur Rath Yatra by the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP). “Ali Miyan, one of the most noted Islamic scholars and the head of the famous Islamic seminary Nadwa College in Lucknow, called me to discuss the (Ayodhya) matter in 1983,” recalls advocate Zafaryab Jilani, one of the most recognisable voices in the legal battle from the Muslim side in the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid land dispute case.

Then a young man, Jilani, who says he got associated with the cause in court by chance, reminisces how information on the matter was scarce at the time. Merits and weaknesses were not known. “It was then that Ali Miyan gave me Rs 2,000 and asked me to get the files from Ayodhya and prepare a note on the historical position of the mosque,” he says. It was also discussed to start a Tahrik, or a movement within the community in support of the Babri Masjid.

This is the story not of an individual but of an organisation. As the nearly 70-year-long legal battle over the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid land dispute in independent India moves towards completion, one name that emerges as the biggest crusader for the Muslim cause is the Babri Masjid Action Committee. The wrangle over the land, where Babri Masjid stood, dates back to 1857 when Maulvi Muhammad Asghar, the muezzin of the mosque, filed a petition before the magistrate complaining that the courtyard of the structure had been forcibly taken over by the mahant of Hanumangarhi. In 1859, the British government got a wall built, separating the places of worship for Hindus and Muslims. Since then till the intervening night of December 22nd and 23rd in 1949, the status quo remained at the site, before idols of Ram and Sita were placed inside the mosque.

Six days after the so-called “emergence” of the idols, on December 29, Babri Masjid was declared a disputed property. Orders were passed barring Muslims from entering the mosque. The main gate was locked and Hindus were given permission for a darshan from a side gate. From the time of being declared a disputed property in 1949 till 1975, the matter remained pending with the sessions court in Faizabad. In 1975, a case was filed in the Allahabad high court, against orders of receivership. Two years later, the case was transferred to the Lucknow bench of the high court. This after the Awadh Bar Association filed a petition claiming jurisdiction of matters of Faizabad/Ayodhya was with the bench at Lucknow.

From 1977, over the next few years, the case remained in limbo. No progress was made as judge after judge recused themselves. Not many from the Muslim side or the Hindu side took much interest in the legal battle. But as things started changing politically with Hindu groups gradually building a movement around the Ram Janmabhoomi campaign, the Muslim side too pulled up its socks.

The initiative from Ali Miyan, who was also the president of the All India Muslim Personal Law Board (AIMPLB), laid the first building blocks of the movement that over the next few years would lead to the formation of the Babri Masjid Action Committee (BMAC)

On January 2, 1986 came a big moment in the dispute as the Faizabad district judge passed orders for opening the locks of the main gate of the Babri Masjid. On the same day, an urgent meeting of the AIMPLB was held, where it was decided to chalk out a campaign strategy in support of mosque.

A meeting of Muslim leaders was held at the residence of noted lawyer Abdul Mannan in Lucknow on January 4. Those present included Azam Khan, the current MP from Rampur and a senior leader of the Samajwadi party. Also present was the-then Congress MLA Sayeeduzzama. Two days later, a larger meeting was called at a house located in one of the narrow byways of Aminabad in Lucknow with around 200 people in attendance. It was in this meeting that the Babri Masjid Action Committee was formed.

Azam Khan and Zafaryab Jilani were elected conveners while Maulana Muzaffar Hussain was made the president. In 1987, civil suits in the case were withdrawn from Faizabad and transferred to the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad high court. As the legal battle continued, it was the Babri Masjid Action Committee (BMAC) under the aegis of the AIMPLB which built up a community movement against the temple agitation being spearheaded by right-wing Hindu organisations and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The situation changed dramatically when the mosque was demolished by right-wing activists on December 6, 1992. Jilani says, “With the Babri mosque being no more and a subsequent Supreme court order of 1994, our focus shifted towards the legal battle. There was pressure on the personal law board to take over the case. The action committee was given the task of the legal battle.”

Since then, for almost a quarter of a century, it’s the Babri Masjid Action Committee that has pursued the legal battle on behalf of different Muslim parties including the Sunni Central Waqf Board, both in the high court and since 2010 in the Supreme Court. The case reached the SC after the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad high court on September 30, 2010 ordered equal division of the land among the three main parties in the title suit: Sunni Central Waqf Board, Nirmohi Akhara and Ram Lalla Virajman.

So what happens to the Babri Masjid Action Committee as the case heads towards conclusion and most likely a judgement by mid-November? Convener Jilani has no ready answers. But he accepts that “things will not be the same as before”. With near certainty of the legal battle reaching a closure, the committee may well become a part of the historical journey of one of the most contentious political, social and legal disputes of contemporary India.

As the Ayodhya land dispute case draws to a close, a News18 series traces the journey of one of the most protracted legal battles in the history of independent India.

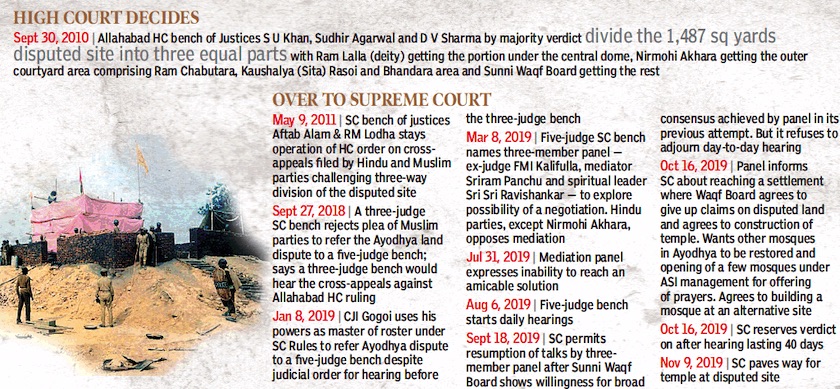

A timeline of the case: Till Oct 2019

From: Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: July 31, 2020: The Times of India

See graphics:

A timeline of the case, Ayodhya (Babri Masjid- Ram Janambhoomi)- 1950-1989

A timeline of the case, Ayodhya (Babri Masjid- Ram Janambhoomi)- 1991-1993

A timeline of the case, Ayodhya (Babri Masjid- Ram Janambhoomi)- 2010-2019

A timeline of the Babri Masjid/ Ram Janambhoomi case: Till Oct 2019

1986: Rajiv Opened Lock, Saffron Got The Key

Avijit Ghosh, Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

From: Nov 10, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The political lexicon of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement

In the complex world of Indian politics, the BJP rules today. The dominant force in the NDA bagged 303 seats out of a possible 543 in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. The saffron party received 37% of the votes, a jump of over 6% since 2014. BJP’s chief rival, Congress, got half: 19% vote share.

The situation was the reverse, 35 years ago. Many young Indians today would find it hard to believe that under the leadership of Rajiv Gandhi, the Congress earned 49% of the votes and a staggering 404 seats in the 1984 general elections.

The BJP, in contrast, picked up less than 8% of the ballot and was reduced to a single-digit party with just two seats in the lower house.

What happened in the years between those two extreme verdicts is a slow but clear shift, from the centre to the right. Social scientists and bureaucrats of the time believe that the Ramjanmabhoomi movement of the late 1980s was central to the legitimisation and mainstreaming of the right in India, which benefited hugely from two of then-Prime-Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s political choices.

One, he nullified the Supreme Court’s 1985 decision to provide maintenance for Shah Bano, a Muslim widow who had been divorced by her husband. That decision was taken to pacify the Muslim conservatives who were agitating against the judgment across the country.

In his book, ‘My Years with Rajiv and Sonia’, former home secretary R D Pradhan recalls having a one-on-one conversation with Gandhi and telling him, “Mr Prime Minister, you are facing a difficult situation, but I feel that you are the natural leader of the Muslim youth, boys and girls, as well as of all young Indians. Do whatever you want, but do not compromise your image as a young and progressive leader.” Rajiv replied, “Pradhanji, don’t forget that I am also a politician.”

The former bureaucrat remembered being “bothered” by those words. “Until that stage, he (Rajiv Gandhi) had risen above the level of the ordinary run of politicians. He had proved that he could be bold and innovative in tackling problems that had been facing India’s polity-…Now it seemed that he had become a prisoner of political compulsions,” he adds.

To balance the political slant and show that he was equally accommodative to Hindu sentiments, Rajiv then made his second major decision in February 1986. He unlocked the gates of Babri Masjid for Hindus to worship.

Writing for The Statesman in May 1986, journalist Neerja Chowdhury said, “A policy of appeasement of both communities being pursued by the government for electoral gains is a vicious cycle which will become difficult to break.” Opening the locks didn’t appease the saffron brigade; it whetted its appetite. There was now a demand for the construction of a Ramjanmabhoomi Mandir on the site of the Babri mosque.

To broaden the movement, the VHP, R S S and BJP hit upon the idea of Ram shilas, bricks which were worshipped and consecrated across villages in various parts of India. These bricks were meant to be used for the construction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya. Some suggest that telecasting Ramayan on DD in 1987 too was part of the outreach to Hindus.

“A large number of Hindus were politically mobilised. But it communalised the whole situation and Hindus and Muslims came dangerously close to confrontation,” wrote social activist Asghar Ali Engineer in the essay, “Hindu-Muslim Relations before and after 1947”. In the 1989 Lok Sabha election that followed, BJP vote share rose to 11% and seats leapfrogged to 85.

But some social scientists believe that the roots of the Indian right’s rise date further back to the 1970s. Political scientist Imtiaz Ahmad feels that the mainstreaming of the right-wing occurred with Jai Prakash Narain’s Bihar movement.

“Until that time, the R S S was seen as an untouchable in Indian politics. During that movement, they came close to the opposition parties because they had interacted in jail during the Emergency. From then on, right-wing forces began to assert themselves in politics. Advani’s rath yatra was an expression and a consequence of this. Rajiv Gandhi may be blamed for opening the lock, but that was incidental in my view. Even if the lock had not been opened, the right-wing forces were ready to galvanise and mount pressure,” he says.

1992

Rao, PM, wanted mosque, temple to stand together

Lucknow:

Before the demolition of Babri Masjid, the then PM Narasimha Rao had asked the Gujarat-based chief architect of the Ram temple project Chandrakantbhai Sompura whether the mosque, too, could be part of the plan and whether the Babri Masjid and a Ram temple could stand next to one another, reports Yusra Husain.

According to Sompura (77), Rao, in seeking his opinion, had been hinting that the mosque could remain where it was and the temple could be constructed from beyond the Ram Chabutra. But the idea could not be realised as Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) opposed it.

“The PM called me up and asked if the mosque, with its three iconic domes, could be part of the design along with the temple. I communicated the idea to VHP, who had roped me in for the project, but it opposed it and the idea got buried in time,” Sompura told TOI over the phone from Ahmedabad.

“VHP was adamant if the 6-foot-by-3-foot space of the khatiya (bed) where Bhagwan Ram was born is not the centre of the Ram mandir, it wouldn’t matter where the temple came up. The Ram mandir had to be built at the very spot where the structure (mosque) was as they believed Lord Ram was born in the area right under the central dome,” he added.

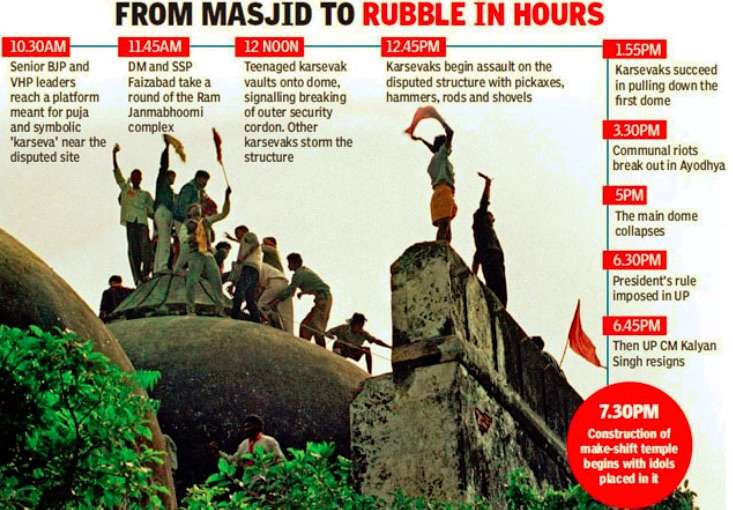

1992 onwards/the events

1992: Demolition of the Babri Masjid

The mosque is razed down by more than lakh supporters of the VHP, the Shiv Sena party and the BJP, prompting nationwide riots between Hindus and Muslims in which more than 2,000 people die. India Today adds:

India Today December 29, 2008

On December 6, 1992, an unprecedented religious frenzy whipped up by an array of Hindu rightwing organisations brought down the medieval Babri Masjid, while the state, represented by 25,000 paramilitary personnel, including the elite NSG, stood like spectators. It was a monumental failure of both the intelligence and security establishments. The widespread riots that followed the demolition rent the nation’s social fabric. “The damage to India’s polity and the reputation of the law enforcers was irreparable,” wrote India Today in December 1992.

End of India Today item

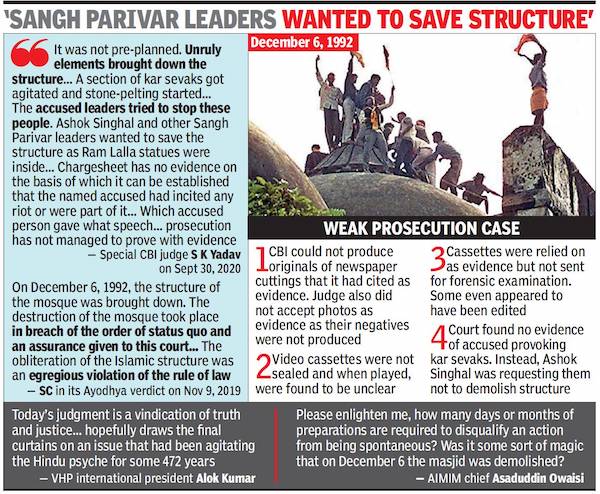

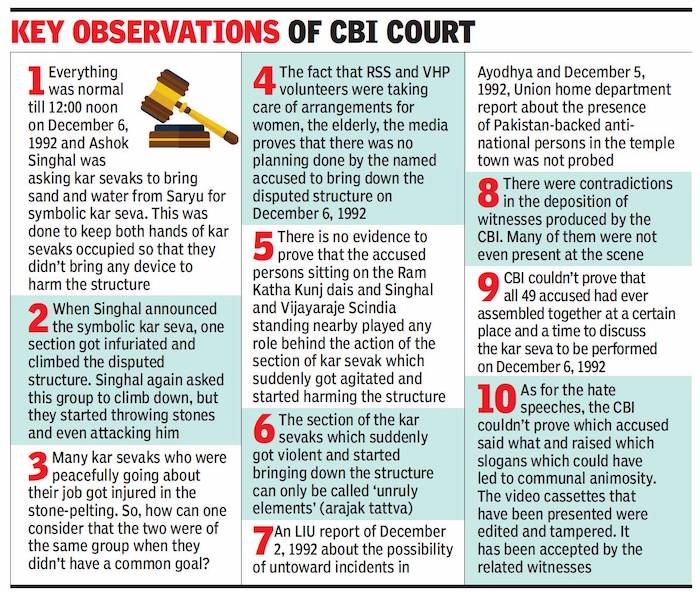

The events of 6 Dec 1992

Avijit Ghosh, December 6, 2017: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, December 6, 2017: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, December 6, 2017: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, December 6, 2017: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, December 6, 2017: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

When hordes of karsevaks brought down the 16th century structure hoping to build a Ram Mandir in its place, many Indians also felt the same way wondering if the nature of national politics had altered forever. The masjid's razing was the final outcome of the Ram Janambhoomi movement which had gathered steam since 1990.

In Naseem, director Saeed Mirza's tender yet unsettling movie on the days leading to the Babri Masjid's demolition, a bedridden old man lives in a mansion of memory reciting Urdu couplets and cocooning himself from the turmoil. He dies the day the mosque is brought down. Mirza once said, the film "was an epitaph to the dream that India gave itself at the time of Independence."

When hordes of karsevaks shouted, "Ek dhakka aur do, Babri Masjid tod do," and brought down the 16th century structure hoping to build a Ram Mandir in its place, many Indians also felt the same way wondering if the nature of national politics had altered forever. The masjid's razing was the final outcome of the Ram Janambhoomi movement which had gathered steam since 1990. The movement was piloted by the Sangh parivar with top BJP and VHP leaders at its forefront.

The political ramifications

Avijit Ghosh, December 6, 2017: The Times of India

Twenty-five years on, the jury is still divided on the long-term impact of the controversial issue. Some believe it was a game-changing moment, others differ. BJP politician Chandan Mitra says that the masjid's demolition marked "a decisive turn" in the nature of Indian politics whereby the idea of "cultural nationalism" overtook the existing "ideological nationalism" that India saw since Independence.

Till then, he says, identity politics was confined to caste and small groups. "This was a supra identity that sought to be established as a kind of majority nationalism. The idea has been gaining ground since then and has established itself as the dominant theme in Indian politics," he says.

Political scientist Imtiaz Ahmed provides a counter. He says the demolition is "a peripheral issue" in Indian politics today, raised sporadically "to influence the electoral process." Even the electoral relevance of Babri Masjid or building the Ram Mandir has declined, he says.

"The BJP recognises this. It is not interested in building the temple but in keeping the issue alive. BJP occasionally talks about it only to use it to polarise the votes and gain some advantage. Look how the Babri Masjid issue is irrelevant in the forthcoming Gujarat election. Even in the UP state election this year, it was not an issue," says Ahmed.

A BJP-led Union government ruled between 1999 and 2004. The saffron party enjoys a majority in the Lok Sabha since 2014. But the issue, as Ahmed says, has never been on the front-burner. Mitra points out that building the temple is "very much" a part of BJP's agenda. However, he says that the Supreme Court order, which says that there can be no construction at the site, has "taken the sting out of the movement." "It will be difficult to violate SC's order unless the two communities are in agreement. That too does not seem likely," he says.

Dalit commentator Chandrabhan Prasad too feels the impact of the masjid's demolition has been limited. "In UP, we've seen BSP and SP roar to power with absolute majority. If the politics had changed permanently, this wouldn't have happened," he says.

Prasad believes that liberalisation had a far greater impact on long-term national politics than the flattening of Babri Masjid. "Dalits have been the biggest beneficiaries of the Constitution and the market economy," he says.

Social scientist and politician Yogendra Yadav provides the big picture saying that the demolition signals a shift in popular opinion. "The middle ground of public opinion decisively shifted towards majoritarianism thereafter. It taught us that secularism cannot be defended merely with instruments of law or arms of the state. We realised that when public opinion shifts, everything else - politics, state institutions, even judiciary, shifts," he says.

"Therefore, the real lesson is that the battle to save secularism has to be fought in the minds of ordinary people. That sadly is a battle secular Indians have not seriously engaged with. This would mean a deeper engagement with our traditions, in Indian languages, and with the common sense of ordinary people. The longer we delay it, the weaker our republic becomes, and susceptible to the kind of thuggery we see today," Yadav says.

Rao govt could have saved Babri: the then Home Secy

Nov 4, 2019: The Times of India

The Babri Masjid could have been saved if there was political will to act and the then PM P V Narasimha Rao did not accept a comprehensive contingency plan of the home ministry prepared before the demolition, claims Madhav Godbole who was the Union home secretary that time.

“If political initiative had been taken at the prime minister’s level, the Mahabharata of this Ramayana could have been avoided,” he says in his new book on the Ayodhya dispute.

Seeking to draw a cogent picture of the events which transpired during the critical period before and after the demolition, Godbole says as PM, Rao “played the most important role in this crucial test match, but, unfortunately, he turned out to be a non-playing captain”.

In “The Babri Masjid-Ram Mandir Dilemma: An Acid Test for India’s Constitution”, the author claims that besides Rao, former prime ministers Rajiv Gandhi and V P Singh also failed to take timely action when the mosque was under serious threat.

In 1992, after detailed discussions with institutions and officers concerned, Godbole says the MHA prepared a comprehensive contingency plan for the takeover of the structure by invoking Article 356 of the Constitution. The Ministry of Law had also cleared the Cabinet note for this purpose, he adds.“For this purpose, it was underlined that action would have to be taken well before the proposed date of commencement of ‘kar seva’...” he writes in the book.

But Rao felt the contingency plan was not workable and dismissed it, he says. PTI

Hindu neighbours ensured food in area under curfew

It was the evening of December 6, 1992. The Babri Masjid had been brought down to a rubble. Mohan Yadav and Sohan Singh were in an animated discussion in Kanpur’s Barra area when they saw about 300 Muslims fleeing, trying to take refuge in the Hari Masjid (mosque painted green) in the area.

“They were carrying lists in hand and knew where Muslim families in the southern part of Kanpur lived. They were hunting the Muslims down. They were carrying weapons and had come prepared,” said Mohan, now in his 60s.

Since the evening of December 6, 1992, and the next few days, Kanpur burnt in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition. Exactly 25 years later, residents — both Hindus and Muslims — those affected by the days of rioting, of sleepless, harrowing nights rife with rumours and true incidents, recall gory details of the tragic month.

Barra-II witnessed the worst carnage. Yadav and Singh, while recalling the “bhayanak” day, remember how they, along with a few others – Mangali Verma and Rajeev Yadav – helped save some of them, though the administration had asked people not to venture close to the riot-hit areas.

“All our lives, we have had tea together over addas. They were like our brothers. How could we have kept away when they were in danger?” said Sohan Singh.

“Even as we encircled the open truck to let Muslims be taken first to Sachendi and then to the refugee camp at Green Park stadium, some police officers asked us to let the truck full of people be pushed into the Pandu river,” added Sohan.

“It started when Bharat Tailors was looted and burnt. Rioters came to Barra. Stuck inside the Hari Masjid, we could hear slogans and sounds of firing. This continued till December 10,” said Mohammad Suleman Jilani, mutawwali (caretaker) of the Hari Masjid.

Jilani said while officers at Govind Nagar police station did not act, Barra police station in-charge Prem Babu Sharma and outpost in-charge Jai Narayan Tiwari, were saving people’s lives. “In Damodar Nagar, a house was set on fire with 13 people inside it when Jai Narayan Tiwari helped them get out through the back door with the help of a rope, even as his own motorbike was burnt," said Jilani.

It was also because of the few Hindus of Barra area that another mosque in Nayi Basti area was saved from rioters, recalled Jilani's family. “When the area was under curfew, these men would under their protection, take a subzi-wallah to the area, so that food be made available to Muslim families under siege,” they said.

1992-1997: the events

1992, Dec 12 Narsimha Rao govt sets up Liberhan Commission to probe 1993 Liberhan Commission starts probe; CBI files chargesheet against LK Advani, 19 others HC starts hearing Ayodhya title suit The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

2003 In a survey asked for by HC, ASI finds evidence of a temple under mosque May 2001 Spl court drops criminal conspiracy charges against Advani and MM Joshi The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

Feb 2002 Karsevaks returning from Ayodhya burnt in a train in Godhra, triggering riots across Gujarat The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

April 2002 Three-judge bench of Sept 2003 CBI court rules that 7 Sangh Pariwar leaders should stand trial for inciting destruction of Babri Masjid. Advani, then deputy PM, was spared June 2009 Liberhan Commission Subramanian Swamy appeals to SC report says 68 guilty of demolition for urgent hearing The Times of India | 6 Dec 2017

1992 onwards/ The legal case

Crime No. 197/1992

Haider Abbas | Babri Masjid: The story of crime # 197/1992| The Milli Gazette 16-30 June 2012 adds:

The Babri Masjid demolition case stems from two cases: Crime No. 197/1992 and Crime No 198/1992.

To begin with, on the day of demolition of Babri Masjid, on Dec 6, 1992, a First Information Report (FIR)-197/1992 was lodged at 5:15 pm by Privambada Nath Shukla (50 years), Station Officer at Police Station (PS), Ramjanum Bhumi, Ayodhya, against lakhs of Karsevaks - names and addresses unknown - Under Section (U/S) 395 (dacoity), 397(dacoity or robbery with attempt to cause death), 332 (causing hurt to deter public servants), 337, 338 (grievous hurt), 295 (injuring or defiling a place of worship with intent to insult religion of any class, 297 (trespass in any place of worship) and 153-A of Indian Penal Code (IPC), which makes promoting enmity between different groups inter alia of religion, read with Section 7 Criminal Law Amendment Act. This eventually led to 49 FIRs being filed against 49 persons with respect to cognizable offences and one FIR relating to non-cognizable offence committed against mediapersons who were recording the demolition of the Babri Masjid and whose video cameras etc were snatched and broken/robbed by the Karsevaks.

On Dec 13, 1992, this case was entrusted for investigation to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). Later Crime No. 198/1992 also was assigned to the CBI for investigation. Both cases were obviously related, hence they were bunched together.

On Sept 8, 1993, the UP government, in consultation with the High Court, created a Special Court at Lucknow (also known as CBI Court), and on 9 Sept 1993, in consultation with HC, the state government referred Crime No. 197/1992 and 47 other cases to the Special Court headed by Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate (ACJM Ayodhya Prakaran) at Lucknow.

Now, since both the cases were under the ambit of CBI, hence it filed a consolidated charge-sheet in Crime No. 198/1992, as well as against thirty-two others accused in Crime No. 197/1992 and in 47 other related cases.

By Aug 27, 1994, all the cases referred to above were committed by ACJM, Lucknow to the Lucknow Sessions Court. CBI also filed a supplementary charge-sheet on Jan 11, 1996, in which it accused another nine persons who were later committed from ACJM, Lucknow to Lucknow Sessions Court on April 10, 1996. These nine persons were a part of the overall 49 accused. All this continued for yet another year and a half, until on Sep 9, 1997 ACJM Ayodhya Prakaran (Session Court), Lucknow charged the accused U/S 147, 153-A, 153-B, 295, 295-A, 505 read with 120-B (conspiracy) IPC. For the first time, in the history of the case, the conspiracy charge was levelled.

This order was challenged by the 33 accused at the Lucknow bench of Allahabad HC through Criminal Revision No. 199/1997 (Moreshwar Save vs. State of UP, 201/97 (Uma Bharti alias Gajra Singh vs. State of UP, 211/97 (RN Srivastata vs State of UP) and 255/97 (Ashok Singhal vs. State of UP) which led to Justice Jagdish Bhalla at the Lucknow bench of Allahabad High court say that the reference of Crime No. 198/1992 was not done in consultation with the HC, hence, the Session Court was not in a position to try the accused. This order, which came on Feb 12, 2001, derailed the entire prosecution process..

The fallout of Justice Bhalla’s : as on May 4, 2001, the CBI Court, Lucknow ordered the proceedings to be dropped against 25 accused including the eight accused in the Crime No. 198/1992 alongwith 13 of Crime No. 197/1992, on the pretext that these persons were covered by Crime No. 198/1992 in respect whereof the CBI court has no jurisdiction.

CBI chose to rise against the order and filed a Criminal Revision 217/2001 CBI vs. Balasahab Thackaray in June 2001. It seven years to reach to a point when the same Criminal Revision was decided and finally on May 20, 2009, Justice Ashok Kumar Singh found it fit to be dismissed. Against the same order CBI has gone to the Supreme Court (SC).

Crime No 198/1992

Haider Abbas | Babri Masjid: The story of crime # 197/1992| The Milli Gazette 1-15 July 2012

Crime No. 198/1992 pertains to high-ranking persons

The second First Information Report (FIR) was lodged on Dec 6, 1992, by Ganga Prasad Tiwari-U/S 153-A, 153-B (imputations prejudicial to national integration) and 505 (statements conducing to public mischief). This case was filed against eight hig BJP/VHP leaders: S/ Shri LK Advani, MM Joshi, Vinay Katiyar, Uma Bharti, Ashok Singhal, Giriraj Kishor, Sadhvi Rithambra and Vishnu Hari Dalmia. The above sections of the Indian Penal Code are cited by police when communal speeches are delivered. The FIR was in context to the speeches delivered in the morning of Dec 6 prior to the demolition.

It took just four days for the state government, on Dec 10, 1992, to entrust the crime for investigation to Crime-Bureau Chief Investigation Department, UP (CB-CID). Six days later, on Dec 16, 1992, the state government, in consultation with the High Court, Lucknow, set up a Special Court of Judicial Magistrate at Lalitpur, UP. On Feb 27, 1993, the charge-sheet was filed U/S 153-A, 153-B, 505, 147 (punishment for rioting), 149 (membership of unlawful assembly, guilty of offence committed in prosecution of common object) of IPC. This charge-sheet was later enhanced by CB-CID at Lalitpur, UP. On March 1, 1993 the Magistrate at Lalitpur, UP took cognizance of the same. Later, on July 8, 1993, the same case was shifted to Rae Bareli, UP.

This was followed by state government requesting the central government, on Aug 25, 1993 to refer Crime No. 198/1992 to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). Finally, the case was handed over to CBI, on Aug 26, 1993. The next move came in the form of state government, in consultation of the HC, creating a Special Court at Lucknow on Sept 8, 1993. On the next day, Sept 9, 1993, in consultation with HC, the state government referred Crime No. 197/1992 as well as 47 other related cases (which stemmed from the same event) to the Special Court headed by the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate (ACJM Ayodhya Prakaran) at Lucknow, UP. This was also called as “CBI Court”.

Next month, on Oct 5, 1993, the CBI filed a consolidated charge-sheet against all the eight high profile accused in the Crime No. 198/1992 and the Crime No. 197/1992. On Oct 8, 1993 the state government referred to it Crime No. 198/1992. The state government then failed to consult the HC before this move. It may be reiterated that the state was then under the Congress-created President’s rule, which served two terms.

The prosecution process took a further step when on Oct 11, 1993, as the ACJM took cognizance of both the cases at Lucknow, and further on Jan 24, 1994, the record which was lying at Rae Bareli, UP was brought to Lucknow. The cases were, thereafter, committed to ACJM, Lucknow, and the case continued until Sept 9, 1997, when the ACJM, Lucknow charged the accused U/S 147, 153-A, 153-B, 295, 295-A, 505 read with 120-B (conspiracy) of IPC. Here for the first time the conspiracy charge was levelled.

The moment the conspiracy charge came into play, the order was challenged by the accused at the Lucknow bench of Allahabad HC which, finally, led Justice Jagdish Bhalla to order on Feb 12, 2001 that since the reference of Crime No. 198/1992 was not done in consultation with the HC, the Sessions Court was in no position to try the accused..

“CBI deleted the conspiracy charge in its supplementary charge-sheet against LK Advani filed at Rae Bareli Court on March 30, 2003, and thus paved the way for his discharge order from the Babri Masjid demolition case. This happened on Sept 19, 2003 by the First Class Magistrate. Later, all the other high-profile accused got the criminal proceedings “stayed” on the same grounds, on Sept 30, 2003 from the HC. Solicitor general RN Trivedi to opposed the Muslim side revision petition, which ultimately had led Justice YR Tripathi at the Lucknow bench of Allahabad High Court, on July 5, 2005, to order that prima facie the charge against all the eight accused, including Advani was maintainable,” informed Zafaryab Jilani, the co-convenor of Babri Masjid Action Committee. The case got a fresh lease of life at Rae Bareli albeit without the conspiracy charge.

End of the item with the heading The legal case

1998-2003

1998: The BJP forms coalition government under Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee.

2001: Tensions rise on the anniversary of the demolition of the mosque. VHP pledges again to build Hindu temple at the site.

January 2002: Mr Vajpayee sets up an Ayodhya cell in his office and appoints a senior official, Shatrughna Singh, to hold talks with Hindu and Muslim leaders.

February 2002: BJP rules out committing itself to the construction of a temple in its election manifesto for Uttar Pradesh assembly elections. VHP confirms deadline of 15 March to begin construction. Hundreds of volunteers converge on site. At least 58 people are killed in an attack on a train in Godhra which is carrying Hindu activists returning from Ayodhya.

March 2002: Between 1,000 and 2,000 people, mostly Muslims, die in riots in Gujarat following the train attack.

BBC adds: More than 50 people died in February 2002 when a train carrying Hindu activists returning to Gujarat from Ayodhya was set alight, allegedly by a Muslim mob.

At least 1,000 people - mainly Muslims - died in the violence in the state that erupted afterwards. Other estimates say the death toll was at least double that. End of the BBC item.

April 2002: Three High Court judges begin hearings on determining who owns the religious site.

2002: The High Court directs the Archaeological Survey of India to excavate the site to determine if a temple lay underneath

January 2003: Archaeologists begin a court-ordered survey to find out whether a temple to Lord Ram existed on the site.

The 2003 charge-sheet

V. Venkatesan | Charge-sheet in Ayodhya case | June 07 - 20, 2003| Frontline

ON May 31, 2003, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) filed a supplementary charge-sheet against Deputy Prime Minister L.K. Advani and seven others, including Union Human Resource Development Minister Murli Manohar Joshi, former Union Minister Uma Bharti, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Vinay Katiyar and Vishwa Hindu Parishad chief Ashok Singhal, in the Babri Masjid demolition case in a Special Court in Rae Bareli, Uttar Pradesh. The report, filed by CBI counsel S.S. Gandhi, contains the statements of 39 witnesses, besides documents and press reports relating to the investigation of case No.198/92 by the agency after September 10, 1993. The development has led to fresh demands from Opposition parties, especially the Communist Party of India (Marxist), that Advani and Joshi should quit the government to enable the CBI to pursue the prosecution of the case in an unbiased manner.

The CBI had filed its consolidated charge-sheet against most of the accused in the case before the Special Court of Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate, Lucknow, on October 5, 1993. The supplementary charge-sheet had to be filed after the Supreme Court upheld the Uttar Pradesh government's notification setting up a Special Court in Rae Bareli to deal with the charges. The accused face charges of inciting communal feelings that led to the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992.

In February 2001, the Allahabad High Court had quashed the charges against Advani and others, citing a procedural lapse, which resulted in the State government transferring the case to a special CBI court without due consultation with the High Court, as required under the law. The Uttar Pradesh government, led by Bahujan Samaj Party leader Mayawati, issued the notification to set up the Special CBI court in Rae Bareli following persistent demand from civil rights groups and Opposition parties.

End of the Frontline item

2003-2010

August 2003: The survey presented evidence of a temple under the mosque. Muslim groups disputed the findings. Mr Vajpayee says at the funeral of Hindu activist Ramchandra Das Paramhans that he will fulfil the dying man's wishes and build a temple at Ayodhya and hopes the courts and negotiations will solve the issue.

September 2003: A court rules that seven Hindu leaders should stand trial for inciting the destruction of the Babri Mosque, but no charges are brought against L.K Advani (later the deputy prime minister) who was also at the site in 1992.

Oct 2004: Mr Advani says his party still has "unwavering" commitment to building a temple at Ayodhya, which he said was "inevitable".

November 2004: A court in Uttar Pradesh rules that an earlier order which exonerated Advani for his role in the destruction of the mosque should be reviewed.

July 2005: Suspected Islamic militants attack the disputed site, using a jeep laden with explosives to blow a hole in the wall of the complex. Security forces kill five people they say are militants, and a sixth who was not immediately identified.

2007: The Supreme Court refuses to admit a review petition on the Ayodhya dispute.

June 2009: The Liberhan commission investigating events leading up to the mosque's demolition submits its report - 17 years after it began its inquiry.

November 2009: There is uproar in parliament as the Liberhan commission's report is published and it blames leading politicians from the Hindu nationalist BJP for a role in the mosque's razing.

July 2010 - On July 27, the court took the initiative for an amicable solution to the dispute when it called on counsel for the contending parties to go into the possibility. But no headway was made. (Reality Views)

September 2010 (Reality Views) adds: The Special Bench, at its Bench of Judicature here, comprising Justices S.U. Khan, D.V. Sharma and Sudhir Agarwal, said that Mr. Tripathi's application lacked merit. It also imposed “exemplary costs” of Rs. 50,000, terming his effort for an out-of-court settlement as a “mischievous attempt.”

Mr. Tripathi's plea was opposed by the Akhil Bhartiya Hindu Mahasabha and the Sunni Central Board of Waqfs, which submitted separate replies to the OSD on September 16. Stating that an amicable solution was not possible, they alleged that the application was mala fide.