Archaeology and Monuments: India

(→Centrally Protected Monuments: India) |

(→Centrally Protected Monuments: India) |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

==A list of the monuments== | ==A list of the monuments== | ||

See [[Centrally Protected Monuments: India ]] | See [[Centrally Protected Monuments: India ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Using them as a stage to ‘right historical wrongs’== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=26_02_2023_024_020_cap_TOI Manimugdha S Sharma, February 26, 2023: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Cracks developed in the ceiling of Diwan-i Aam at Agra Fort after a G20 event was held there on February 11. Experts have speculated that loud music from speakers installed inside the 17th-century building caused the cracks. But this didn’t deter the Maharashtra government from holding another event at the Unesco World Heritage Site on February 19 to celebrate the birth anniversary of Maratha king Shiva ji, who had felt humiliated in the court of emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, in the same building, back in 1666. | ||

| + |

Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which had originally denied permission for the Shiv aji event, clarified that it was held away from the damaged part of the building. But the desire to symbolically avenge Shiva ji 357 years after his humiliation seems to have trumped concerns about heritage conservation.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Not The First Time ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

This has been a perennial problem of Indian heritage conservation. Right at its birth, independent India set out on a journey to ‘right historical wrongs’ when it decided to build a new temple at Somnath in Gujarat, swatting aside opposition from heritage conservationists and archaeologists, and completely dismantling the ruins of the older temple ravaged by invasions and time that contained, to borrow Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous phrase, “palimpsest pasts”. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

K M Munshi, who was the prime mover of the bid to rebuild the Somnath Temple and was backed to the hilt by home minister Sardar Patel, acknowledged that the proposal to rebuild the temple drew the ire of archaeologists. “In the beginning, some persons, more fond of dead stonesthan live values, pressed the point of view that the ruins of the old temple should be maintained as an ancient monument. We were, however, firm in our view, that the temple of Somanatha was not an ancient monument; it lived in the sentiment of the whole nation and its reconstruction was a national pledge,” Munshi wrote in his 1951 book, ‘Somanatha: The Shrine Eternal’.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' History Before Heritage ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Preserving history was not Munshi’s concern, making history was. And he made it amply clear when he said the temple’s “preservation should not be a mere matter of historical curiosity”. He wrote: “Some of my scholar friends had hard things to say about me for my ‘vandalism’. They forgot that I am fond of history, but fonder still of creative values. ” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

ASI continued to oppose the move. This resulted in Sardar Patel’s intervention in 1948 when he said (as quoted by Munshi), “…. The Hindu sentiment in regard to this temple is both strong and widespread. In the present conditions, it is unlikely that that sentiment will be satisfied by mere restoration of the templeor by prolonging its life. The restoration of the idol would be a point of honour and sentiment with the Hindu public. ” | ||

| + | |||

| + | What was striking in the Somnath episode, as Dutch anthropologist Peter van der Heer observes, was that the opposition of archaeologists and heritage conservationists was described as a “colonial view” that had to be dispensed with as India had become free. The logic of this flowed from the fact that the site was designated an “ancient monument” during the viceroyalty of Lord Curzon (1899-1905) – a stunning inversion of the decolonisation argument.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Curzon’s Forgotten Work ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Lord Curzon, mostly reviled by Indian nationalists as the man who partitioned Bengal, had a rather positive contribution to Indian archaeology. He organised both conservation and restoration works at various Indian monuments, including the Taj Mahal and the fort at Agra, and the Red Fort in Delhi. A plaque at one of Shah Jahan’s buildings at Agra Fort still commemorates Curzon’s contribution. He came down hard on the practice of whitewashing and plastering monuments. The plastering work done at Diwan-i Aam at Agra Fort displeased him when he visited it in 1899. The viceroy was told that plastering was done to preserve the integrity of the stonework that had decayed. Curzon demanded that repainting work be stopped and the building preserved in an ‘as is where is’ state. He was also displeased to find that the ceilings of both the Diwan-i Aam and Diwan-i Khas at Delhi’s Red Fort were being repainted, and thought the work was “uniformly bad”. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Curzon outlined his conservation philosophy in Indian Archaeology: “Better the perished and faded originals than a series of modern restorations. ”Curzon got some of the missing tilework behind the Mughal throne at Delhi’s Diwan-i Aam installed. It had been taken away during the loot of 1857. He got an Italian craftsman to travel to Delhi to make substitutes for the missing panels as a Venetian craftsman named Austin de Bordeaux had made the originals for emperor Shah Jahan. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

But Curzon’s more lasting impact was the landscaping of the Mughal gardens at the Taj and at Red Fort in Delhi that became a template for all subsequent heritage works in the subcontinent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Delhi works were done for the 1903 Durbar. When the Durbar of 1911 was organised by viceroy Lord Hardinge, he had Curzon’s model to follow. “The fort at Delhi which had been a wilderness was sparkling with fountains, water runnels, green lawns and shrubberies…” Hardinge wrote in his 1948 memoir, ‘My Indian Years, 1910-1916’. The 1911 Durbar was quite the statement in imperial pomp and pageantry and had the Mughal citadel as its centrepiece. King George V and Queen Mary made an appearance before the public from the ramparts of the Mughal palace complex, mimicking the jharokha darshan of the Mughal emperors of yore. But it was lambasted by Indian nationalists, who had much to suspect about the British intent.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | ''' Rules Made, Then Flouted ''' | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Historian Julie Codell writes that all three durbars (1877, 1903, 1911) had their trenchant critics in the Indian press:“The radical Amrita Bazar Patrika described the viceroy’s speech as ‘full of the usual platitudes’. The Bombay Gazette opposed the Durbar due to excessive costs. The Bengalee asked, ‘What has Lord Curzon done to revive the industries in British India?’ The Hindoo Patriot called the 1903 Durbar ‘an extravagant waste’ and considered its exhibition merely a ‘symbol of Britain’s power and glory in the East’. The Anglo-Indian Statesman praised the exhibition, then criticised it as ‘a glorified bazaar’ in which a ‘European mind supplies the outline, the measurement, the broad character; Oriental ingenuity and fancy are confined to the ornament’,” Codell writes in ‘On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911’. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Challenges to heritage conservation kept coming in postcolonial India too. In 1997, renowned composer Yanni held a concert with the Taj Mahal as the backdrop, drawing howls of protests from environmentalists and heritage conservationists who argued that loud music might impact the 17th-century mausoleum and bright lighting might attract bugs whose excrement could corrode its marble. The concert went ahead as planned with court help, but the tomb was found littered with bugs the following morning, proving conservationists’ fears right. This resulted in the Supreme Court imposing certain conditions for noise and light levels around the monument. But not many lessons were learnt as the UP government a few years later locked horns with the ASI to illuminate the Taj for the ‘Taj Mahotsav’ festival. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The recent incident at the Agra Fort only shows why protecting heritage is a tough battle in India.

The writer is a journalist doing his PhD in history at the University of British Columbia, Canada. | ||

[[Category:History|AARCHAEOLOGY AND MONUMENTS: INDIAARCHAEOLOGY AND MONUMENTS: INDIA | [[Category:History|AARCHAEOLOGY AND MONUMENTS: INDIAARCHAEOLOGY AND MONUMENTS: INDIA | ||

Latest revision as of 20:17, 8 March 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit]

[edit] 1949- 2010

As the govt wants to amend heritage laws, experts think aloud about ways to protect buildings and beat the perception that history impedes development

A couple of weeks after the great Russian artist Nicholas Roerich passed away in Himachal Pradesh, an exhibition of his works was held in Delhi. It was late December 1947 and India was independent. Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru came for the inauguration.

“I hope that when we are a little freer from the cares of the moment, we shall pay very special attention to the ancient cultural monuments of the country, not only just to protect them from decay but somehow to bring them more in line with our education, with our lives, so that we may imbibe something of the inspiration that they have, Pandit Nehru said while inaugurating the exhibition. A profound expression of intent, one would think. At that point in 1947, there were 2,826 protected monuments in India. Yet govern mental apathy towards them was of monumental proportions. Nehru was reminded of this by many events and people. Leela Shiveshwarkar, an author and a leading design er of that time, had written an article in The Times of India in 1949 in which she had called this negligence “inexcusable“. And no, she wasn't willing to buy the PM's argument that there were more pressing concerns.

“The government must take immediate steps to do all that is possible for these monuments. Let it not be said that there are other more pressing problems. There can be no other problem in relation to time more pressing than this. These are the only things which India can look back to as her rightful heritage, and if these are lost through sheer neglect, what else is left?“ Shiveshwarkar said in her piece.

Two years later, Parliament passed the Ancient and Historical Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Declaration of National Importance) Act, 1951, and added 450 other monuments to the previous list.

Nehru had kept his word.

But the inadequacy of the leg islation was discovered soon, as Parliament had to sanction every new inclusion in the list. An amendment Bill was proposed. While debating it in 1953, Congress MP from Madras, K Rama Rao, liked the Bill for its “judicious mixture of tombs and tem ples“, but won dered how the archaeolo g y department was helping Nehru in his “discovery of India every day“.

The 1951 law was repealed and a new one enacted as The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, followed by a set of rules in 1959. This was the most comprehensive legislation for the protection of heritage.

Then in 2010, the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) Act came about as an amendment to the principal Act. Among many things, this amendment introduced the concept of prohibited and regulated zones. And it's this concept that the Modi government wants to amend to allow “public works“ in the prohibited zone of 100 metres of a protected monument.

The prohibition clause has been a contentious issue since the 2010 amendment, with many arguing that heritage buildings act as obstacles to development. A general impression was thus wrongly created that heritage and modernity are contradictory . That this clause is now up for amendment shows that this gulf is deemed unbridgeable.

“Heritage and modernity can coexist to enrich the character of urban space. The adaptive reuse of historical structures could be financially sustainable too,“ said Tathagata Neogi, a British-trained archaeologist who now conducts heritage walks in Kolkata.

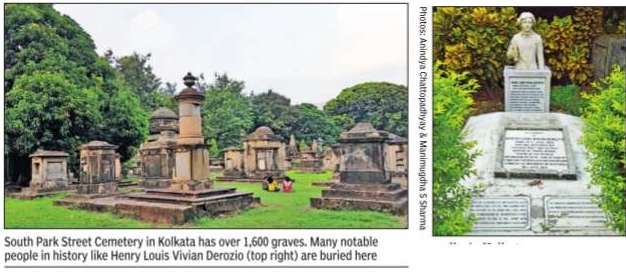

To illustrate his point, he gave the example of South Park Street Cemetery in Kolkata. “It is suffering from an acute lack of funds. Although they have recently started a ticketing system, more can be done to generate revenue. This cemetery , containing more than 1,600 graves of eclectic architecture, could be converted into an open-air, nuanced museum of colonialism using cutting-edge technology like augmented reality ,“ Neogi said.

He continued, “Many old buildings in north Kolkata are crumbling due to lack of maintenance.Some of these families do not want to give up their ancestral homes, but lack the training and resources to maintain them. What if we can train them and show them how to make their properties profitable?“ Neogi also said that old structures could be turned into “offices, shopping centres or themed restaurants without pulling them down and building characterless new concrete, steel and glass structures“.

Delhi, for all its abundance of heritage, strangely , has very few heritage hotels, resorts and homestays. That raises the fundamental question: can heritage be monetised in Delhi? “A very good question. I really think this needs to be pursued urgently in Delhi,“ said Swapna Liddle, convenor of Intach Delhi Chapter. “A good starting point has to be for all stakeholders to have a dialogue. It is important for owners of heritage buildings to not only be aware of their responsibilities and the development restrictions their properties are subject to, but to be informed of the incentives and benefits that the state can give them. The latter must of course be first spelt out and formulated--tax exemptions, loans for conservation, technical advice, and the ability to change the use to commercial purposes, subject to the use not being such as will damage the heritage character of the building.“

Neogi also stressed on the need to have a “more accommodating urban development policy that goes beyond the simple binary of heritage vs development“.

This should be Delhi's, nay India's pressing concern.

[edit] Centrally Protected Monuments: India

[edit] A list of the monuments

See Centrally Protected Monuments: India

[edit] Using them as a stage to ‘right historical wrongs’

Manimugdha S Sharma, February 26, 2023: The Times of India

Cracks developed in the ceiling of Diwan-i Aam at Agra Fort after a G20 event was held there on February 11. Experts have speculated that loud music from speakers installed inside the 17th-century building caused the cracks. But this didn’t deter the Maharashtra government from holding another event at the Unesco World Heritage Site on February 19 to celebrate the birth anniversary of Maratha king Shiva ji, who had felt humiliated in the court of emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, in the same building, back in 1666.

Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), which had originally denied permission for the Shiv aji event, clarified that it was held away from the damaged part of the building. But the desire to symbolically avenge Shiva ji 357 years after his humiliation seems to have trumped concerns about heritage conservation.

Not The First Time

This has been a perennial problem of Indian heritage conservation. Right at its birth, independent India set out on a journey to ‘right historical wrongs’ when it decided to build a new temple at Somnath in Gujarat, swatting aside opposition from heritage conservationists and archaeologists, and completely dismantling the ruins of the older temple ravaged by invasions and time that contained, to borrow Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous phrase, “palimpsest pasts”.

K M Munshi, who was the prime mover of the bid to rebuild the Somnath Temple and was backed to the hilt by home minister Sardar Patel, acknowledged that the proposal to rebuild the temple drew the ire of archaeologists. “In the beginning, some persons, more fond of dead stonesthan live values, pressed the point of view that the ruins of the old temple should be maintained as an ancient monument. We were, however, firm in our view, that the temple of Somanatha was not an ancient monument; it lived in the sentiment of the whole nation and its reconstruction was a national pledge,” Munshi wrote in his 1951 book, ‘Somanatha: The Shrine Eternal’.

History Before Heritage

Preserving history was not Munshi’s concern, making history was. And he made it amply clear when he said the temple’s “preservation should not be a mere matter of historical curiosity”. He wrote: “Some of my scholar friends had hard things to say about me for my ‘vandalism’. They forgot that I am fond of history, but fonder still of creative values. ”

ASI continued to oppose the move. This resulted in Sardar Patel’s intervention in 1948 when he said (as quoted by Munshi), “…. The Hindu sentiment in regard to this temple is both strong and widespread. In the present conditions, it is unlikely that that sentiment will be satisfied by mere restoration of the templeor by prolonging its life. The restoration of the idol would be a point of honour and sentiment with the Hindu public. ”

What was striking in the Somnath episode, as Dutch anthropologist Peter van der Heer observes, was that the opposition of archaeologists and heritage conservationists was described as a “colonial view” that had to be dispensed with as India had become free. The logic of this flowed from the fact that the site was designated an “ancient monument” during the viceroyalty of Lord Curzon (1899-1905) – a stunning inversion of the decolonisation argument.

Curzon’s Forgotten Work

Lord Curzon, mostly reviled by Indian nationalists as the man who partitioned Bengal, had a rather positive contribution to Indian archaeology. He organised both conservation and restoration works at various Indian monuments, including the Taj Mahal and the fort at Agra, and the Red Fort in Delhi. A plaque at one of Shah Jahan’s buildings at Agra Fort still commemorates Curzon’s contribution. He came down hard on the practice of whitewashing and plastering monuments. The plastering work done at Diwan-i Aam at Agra Fort displeased him when he visited it in 1899. The viceroy was told that plastering was done to preserve the integrity of the stonework that had decayed. Curzon demanded that repainting work be stopped and the building preserved in an ‘as is where is’ state. He was also displeased to find that the ceilings of both the Diwan-i Aam and Diwan-i Khas at Delhi’s Red Fort were being repainted, and thought the work was “uniformly bad”.

Curzon outlined his conservation philosophy in Indian Archaeology: “Better the perished and faded originals than a series of modern restorations. ”Curzon got some of the missing tilework behind the Mughal throne at Delhi’s Diwan-i Aam installed. It had been taken away during the loot of 1857. He got an Italian craftsman to travel to Delhi to make substitutes for the missing panels as a Venetian craftsman named Austin de Bordeaux had made the originals for emperor Shah Jahan.

But Curzon’s more lasting impact was the landscaping of the Mughal gardens at the Taj and at Red Fort in Delhi that became a template for all subsequent heritage works in the subcontinent.

The Delhi works were done for the 1903 Durbar. When the Durbar of 1911 was organised by viceroy Lord Hardinge, he had Curzon’s model to follow. “The fort at Delhi which had been a wilderness was sparkling with fountains, water runnels, green lawns and shrubberies…” Hardinge wrote in his 1948 memoir, ‘My Indian Years, 1910-1916’. The 1911 Durbar was quite the statement in imperial pomp and pageantry and had the Mughal citadel as its centrepiece. King George V and Queen Mary made an appearance before the public from the ramparts of the Mughal palace complex, mimicking the jharokha darshan of the Mughal emperors of yore. But it was lambasted by Indian nationalists, who had much to suspect about the British intent.

Rules Made, Then Flouted

Historian Julie Codell writes that all three durbars (1877, 1903, 1911) had their trenchant critics in the Indian press:“The radical Amrita Bazar Patrika described the viceroy’s speech as ‘full of the usual platitudes’. The Bombay Gazette opposed the Durbar due to excessive costs. The Bengalee asked, ‘What has Lord Curzon done to revive the industries in British India?’ The Hindoo Patriot called the 1903 Durbar ‘an extravagant waste’ and considered its exhibition merely a ‘symbol of Britain’s power and glory in the East’. The Anglo-Indian Statesman praised the exhibition, then criticised it as ‘a glorified bazaar’ in which a ‘European mind supplies the outline, the measurement, the broad character; Oriental ingenuity and fancy are confined to the ornament’,” Codell writes in ‘On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911’.

Challenges to heritage conservation kept coming in postcolonial India too. In 1997, renowned composer Yanni held a concert with the Taj Mahal as the backdrop, drawing howls of protests from environmentalists and heritage conservationists who argued that loud music might impact the 17th-century mausoleum and bright lighting might attract bugs whose excrement could corrode its marble. The concert went ahead as planned with court help, but the tomb was found littered with bugs the following morning, proving conservationists’ fears right. This resulted in the Supreme Court imposing certain conditions for noise and light levels around the monument. But not many lessons were learnt as the UP government a few years later locked horns with the ASI to illuminate the Taj for the ‘Taj Mahotsav’ festival.

The recent incident at the Agra Fort only shows why protecting heritage is a tough battle in India. The writer is a journalist doing his PhD in history at the University of British Columbia, Canada.

[edit] Maintenance

[edit] Adopt A Heritage scheme/ 2018

Yuthika Bhargava, May 13, 2018: The Hindu

What is it?

The ‘Adopt a Heritage: Apni Dharohar, Apni Pehchaan’ scheme is an initiative of the Ministry of Tourism, in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and the Archaeological Survey of India. It was launched in September 2017 on World Tourism Day by President Ram Nath Kovind. Under it, the government invites entities, including public sector companies, private sector firms as well as individuals, to develop selected monuments and heritage and tourist sites across India. Development of these tourist sites calls for providing and maintaining basic amenities, including drinking water, ease of access for the differently abled and senior citizens, standardised signage, cleanliness, public conveniences and illumination, along with advanced amenities such as surveillance systems, night-viewing facilities and tourism facilitation centres. The sites/monument are selected on the basis of tourist footfall and visibility and can be adopted by private and public sector companies and individuals — known as Monument Mitras — for an initial period of five years.

The Monument Mitras are selected by the ‘oversight and vision committee,’ co-chaired by the Tourism Secretary and the Culture Secretary, on the basis of the bidder’s ‘vision’ for development of all amenities at the heritage site. There is no financial bid involved. The corporate sector is expected to use corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds for the upkeep of the site. The Monument Mitras, in turn, will get limited visibility on the site premises and on the Incredible India website. The oversight committee also has the power to terminate a memorandum of understanding in case of non-compliance or non-performance.

How did it come about?

This is not the first time the government has tried to rope in the corporate sector to help maintain tourist sites and monuments. In one such attempt, the government in 2011 formed a National Culture Fund. Since then, 34 projects have been completed under it through public-private partnerships. Another similar scheme under the UPA government was ‘Campaign Clean India,’ in which the government had identified 120 monuments/destinations. Under this scheme, the India Tourism Development Corporation had adopted Qutab Minar as a pilot project in 2012, while ONGC adopted six monuments — Ellora Caves, Elephanta Caves, Golkonda Fort, Mamallapuram , Red Fort and Taj Mahal — as part of its CSR.

Why does it matter?

The project kicked up a storm after reports that private entity Dalmia Bharat, under an MoU, would build infrastructure and maintain the iconic Red Fort. Dalmia Bharat has committed Rs. 25 crore for the purpose. The Opposition termed it an attack on the idea of India, alleging that the government was handing over the symbol of India’s independence to private parties. The government said the scheme would help to increase tourist footfall.

What lies ahead?

Notwithstanding criticism, the government intends to expand the ‘Adopt a Heritage’ scheme. Under the scheme, the government has put up a list of over 93 ASI monuments that can be bid for by private and public sector firms, as well as individuals. This is a pretty small list, as the ASI protects 3,686 ancient monuments and archaeological sites, including 36 world heritage sites. So far, 31 agencies or Monument Mitras have been approved to adopt 95 monuments/tourist sites. However, only four MoUs have been signed. These are between the Ministry of Tourism, the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India and the Government of Jammu & Kashmir for Mt. Stok Kangri, Ladakh; the Ministry of Tourism, the Adventure Tour Operators Association of India and the Uttarakhand government for trail to Gaumukh; the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry of Culture, the ASI and Dalmia Bharat for the Red Fort (in Delhi) and the Gandikota Fort (in Andhra Pradesh). The government is hopeful of expediting the MoUs with selected entities in the next two months.

[edit] Missing monuments

[edit] 2018

From: January 24, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

Total number of monuments under ASI's watch, state-wise, as in January 2018

[edit] See also

For Rock Carvings found in Delhi's JNU, see Delhi: J