Turtles: India

(→HABITATS, SANCTUARIES) |

(→Cantor’s giant softshell turtle (Pelochelys cantorii’')) |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

The day the six turtles hatched was unforgettable. After all the waiting and hoping that the flood hadn’t harmed them, I’d almost given up. But nature prevailed and we could release the hatchlings into the wild. As I watched them move into the river, I knew I was looking at the descendants of a truly ancient species, carrying so many of our world’s marvels with them. | The day the six turtles hatched was unforgettable. After all the waiting and hoping that the flood hadn’t harmed them, I’d almost given up. But nature prevailed and we could release the hatchlings into the wild. As I watched them move into the river, I knew I was looking at the descendants of a truly ancient species, carrying so many of our world’s marvels with them. | ||

| + | =See also= | ||

| + | [[Olive ridley turtle: India ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Turtles: India]] | ||

[[Category:Fauna|T | [[Category:Fauna|T | ||

| Line 98: | Line 102: | ||

TURTLES: INDIA]] | TURTLES: INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:Places|T | [[Category:Places|T | ||

| + | TURTLES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Fauna|T TURTLES: INDIA | ||

| + | TURTLES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|T TURTLES: INDIA | ||

| + | TURTLES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|TURTLES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Places|T TURTLES: INDIA | ||

TURTLES: INDIA]] | TURTLES: INDIA]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:25, 14 April 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] HABITATS, SANCTUARIES

[edit] Turtle nurseries

[edit] Goa

Gauree Malkarnekar, April 29, 2023: The Times of India

From: Gauree Malkarnekar, April 29, 2023: The Times of India

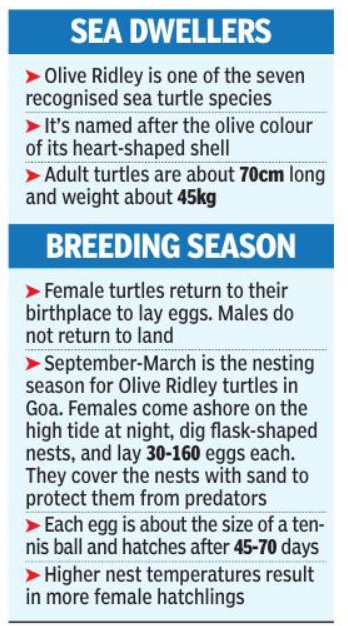

On a moonlit September night, the waves bring in more than the usual flotsam and jetsam to Goa’s shore. Female Olive Ridley turtles waddle in, and instinctively dig a nest in the sands to lay an average of 100 eggs each. These are the first arrivals, and more will follow till March, mainly on the beaches of Morjim, Mandrem, Galgibaga and Agonda. The journey of the Olive Ridley – the smallest sea turtle species – from feeding grounds to nesting grounds, covering thousands of kilometres across seas, is one of the most remarkable journeys in the animal kingdom.

In Goa, the sightings have become more common over the years. Up until 2015-16, the number of nests at Morjim was in the single digits, but in 2022-23 there were 55 nests. The hatchlings will keep emerging from the four turtle nesting sites till May. This season, Goa is expected to touch a record 14,000 hatchlings.

“In 2021-22, Olive Ridley turtles made 93 nests across Morjim, Mandrem, Galgibaga and Agonda, laying 10,025 eggs. This year, the number of nests has gone up to 157, with altogether 16,708 eggs. As the survival rate for hatchlings is 90%, we are expecting 14,000 hatchlings this season,” said Goa’s chief conservator of forests Saurabh Kumar.

Protection Started In 1970s

But Goa was not always a nesting paradise for sea turtles. Lack of awareness until some decades ago meant turtles were poached for their meat and eggs. In the 1970s, Capt. Gerald Fernandes in Morjim and Fr Mariano in Galgibaga pioneered a community turtle conservation effort. Four teenage boys from the fishing community who were engaged by Fernandes at Morjim – Rajan Halarnkar, Trivikram Morje, Dnyneshwar Takkar and Avelino D’Silva – continue to play vital roles in the programme that’s now run by the forest department.

“The men patrol the coast on foot during the turtle nesting season every night, covering 5-6 km from Morjim to Mandrem to look for eggs. Any eggs found beyond the 40m fenced area are carefully collected in a bucket and kept in protected nests within the fenced area. These eggs must be moved without the slightest turning, or the yolk can get spoilt,” said a ground volunteer.

Local Commitment Is Key

Employing boys from the community means that local shack owners are willing to help keep the beaches silent and devoid of bright lights, making it easy for the turtles to find their nesting ground. A recent notification of no-take and silent zones on nesting beaches has further helped create a safe nesting environment. Besides keeping artificial lighting around the nesting habitats under check, the ground workers must ensure that the hatchlings make it to the sea quickly enough to avoid death by dehydration. They also need to be protected from dogs and predatory birds.

“The contribution of sea turtle guards and shack owners, who are all locals and have been tirelessly working for the last two decades, is much to be appreciated,” said Sujeet Kumar Dongre from the Centre for Environment Education, who is an expert helping the state forest department with conservation efforts. “I have personally seen and experienced their passion and commitment. The increase in nests that we see today is the collective effort of the forest department and locals. ”

Lifeguards and beach safety teams have been roped in over the years, leading to better recording of nests all along the beach stretch, said Dongre. Recently, nests were found on the busy Candolim, Calangute and Vagator beaches and moved to the safety of the Morjim site.

[edit] Turtle Wildlife Sanctuary, Varanasi

[edit] 2019: closure or relocation

Neha Shukla, Nov 13, 2019: The Times of India

Three decades after it was declared India’s first and so far only protected area dedicated to the conservation of freshwater turtle species, Varanasi’s Turtle Wildlife Sanctuary is being denotified by the UP government in preparation for a possible “relocation” to the Allahabad-Mirzapur stretch of the Ganga.

The prod to denotify the sanctuary first came two years ago, when the Union ministry of environment and forests wrote to the state government that the ghats were under threat. Amid opposition to the move from conservationists, it emerged that the Centre’s 1,620km national waterways project was to pass through the turtle habitat.

Sources said the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) had conducted a feasibility study and found the Allahabad-Mirzapur stretch of the river suitable for the relocation of the sanctuary. The proposal was “reviewed and approved in principle” during a recent meeting of the state wildlife board, chaired by CM Yogi Adityanath.

The sanctuary, spanning the 7km stretch from Ramnagar Fort to the Malviya railroad bridge, was notified as the country’s first freshwater turtle sanctuary under the Ganga Action Plan in 1989. The idea of a sanctuary was married to the concept of releasing four carnivorous species of turtles for organic cleaning of the Ganga.

Since Kathawa (Aspederites gangeticus), Sundari Kachua (Lissemys punctata), Dhond (Kachuga dhongoka) and Pacheda (Pangshuratecta) are carnivorous turtles, it was expected that they would feed on half-burnt corpses floating in the waters of the Ganga.

Turtle eggs were secured from the Chambal river, hatched at the Sarnath breeding centre and released in the river. The state government subsequently banned sand mining in the area to save the nesting turtles, leading to sand accumulation and increased sedimentation that seemed to create a new set of challenges. Flagging this as a threat to the ghats, the environment ministry wrote to the state government in 2017 seeking a remedy.

Since a wildlife sanctuary can only be denotified, Turtle Wildlife Sanctuary will have to be reborn as a new habitat as and when it is shifted.

The sanctuary is being denotified by the UP govt for relocation after the Centre said the ghats in Varanasi were under threat

[edit] Species

[edit] Cantor’s giant softshell turtle (Pelochelys cantorii’')

Sep 18, 2021: The Times of India

‘Cantor’s giant softshell turtles once lived with dinosaurs — they face extinction now’ Ayushi Jain is a conservation ecologist and a National Geographic Photo Ark EDGE Fellow. Sharing her insights with Times Evoke Inspire, Ayushi discusses her efforts to save a remarkable turtle species: My work focuses on protecting the Cantor’s giant softshell turtle or Pelochelys cantorii, a species over 140 million years old. This turtle actually predates human beings — its origins are traced to when dinosaurs roamed on Earth. But today, with habitat destruction, hunting and harmful fishing, this giant turtle — an evolutionary marvel — faces extinction. As a conservation ecologist, I’m working in collaboration with the Geographical Society of London and National Geographic to save the species.

My work is located amidst the riverbanks of Kasaragod, Kerala.

Kasaragod is in northern Kerala. I work around the Chandragiri river there. This is surrounded by fields, with little forested area left.

In some places, the Cantor’s giant softshell turtle is consumed. I had to gain trust in the local community if I wanted that to change. Today, people call me when they see a turtle being sold for meat.

We’ve also convinced many villagers about the turtle being necessary for their wellbeing. The Cantor’s turtle balances the aquatic ecosystem — without it, fish populations would increase, causing an oxygen deficit in the river. This would cause fish to perish and the river to get polluted.

So far, I’ve seen the turtle just thrice in the wild. This species is very shy. Most freshwater turtles like to bask — they come out on the sanded surface of rivers and sit in the warmth, their body temperature changing with the ambient temperature. But this turtle hides and it can also be aggressive.

I help fishermen release turtles caught accidentally as bycatch — but while we’re taking the hook harming the turtle off, it can take a finger off you. Softshell turtles can retract their neck inside their shell and whip it out very fast to bite. Cantor’s turtles also grow to over three feet and 100 kilograms.

Yet, they move very fast. Lacking a protective hard shell, they don’t want to be near humans — that’s a wish we should respect.

The Cantor is a rare freshwater turtle which also travels to the seaside. But if you build a dam in-between, the turtle can’t move which inhibits its life cycle. Another major challenge is sand mining — in Kasaragod, illegal miners extract sand from the river, carrying this away in boats at night. There are very few sandbanks left. But turtles need these to lay eggs. Such mining is damaging turtle populations, which also face dams flooding nesting sites.

The day the six turtles hatched was unforgettable. After all the waiting and hoping that the flood hadn’t harmed them, I’d almost given up. But nature prevailed and we could release the hatchlings into the wild. As I watched them move into the river, I knew I was looking at the descendants of a truly ancient species, carrying so many of our world’s marvels with them.

[edit] See also

Turtles: India