India, the names of

(→Bharat In the constitution) |

(→Name: India, not Hindustan) |

||

| Line 355: | Line 355: | ||

Milan , a film starring Dilip Kumar and Ranjana that opened during the week, was an adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore's story Noukadubi ( The Wreck ). It was Dilip Kumar's first film for Devika Rani’s Bombay Talkies studio. | Milan , a film starring Dilip Kumar and Ranjana that opened during the week, was an adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore's story Noukadubi ( The Wreck ). It was Dilip Kumar's first film for Devika Rani’s Bombay Talkies studio. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Bharat In the constitution== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=06_09_2023_030_013_cap_TOI Sep 6, 2023: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: Bharat and India, debates in the Constituent Assembly.jpg|Bharat and India, debates in the Constituent Assembly <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=06_09_2023_030_013_cap_TOI Sep 6, 2023: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

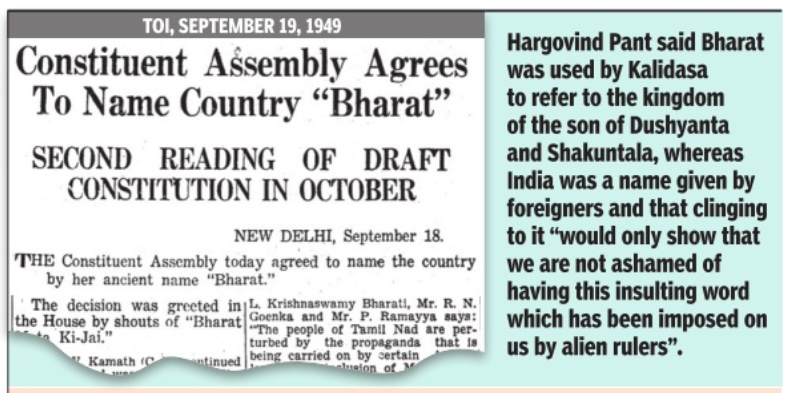

| + | The name ‘Bharat’ wasn’t there in the first draft of India’s Constitution introduced by the chairman of the drafting committee, BR Ambedkar, on November 4, 1948. Although some members flagged the omission of a native name, the debate on this took place almost a year later when the work on finalising the text was coming to an end.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | On September 18, 1949, Ambedkar moved the following amendment to draft Article 1, which mentions the country’s name: “India, that is, Bharat shall be a Union of States.” But Assembly member HV Kamath said this was a clumsy construction and a constitutional slip. He suggested two alternatives: “Bharat, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States” or “Hind, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States”. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Kamath cited the example of Ireland: “The name of the State is Eire, or, in the English language, Ireland.” He wanted to specify “in the English language, India” because in many other countries India was still known as ‘Hindustan’, “and all natives of this country are referred to as Hindus, whatever their religion may be…”

| ||

| + | Asked to pick one name for his amendment, Kamath chose “Bharat, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States.” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Then followed an intense debate in which members Seth Govind Das, Kamalapathi Tripathi, Kallur Subba Rao, Ram Sahai and Har Govind Pant passionately argued for Bharat.

Das said India was not an ancient word and was not found in the Vedas. It was only used after the Greeks came to India, while Bharat was to be found in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Brahmanas, the Mahabharata and the Puranas, as well as in Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang’s writing. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Das suggested “Bharat known as India also in foreign countries”. He said the name was not backward-looking but befitted India’s history and culture. “If we do not arrive at correct decisions in regard to these matters the people of this country will not understand the significance of self-government.” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Kallur Subba Rao said the name India came from Sindhu or Indus, and the name Hindustan suited Pakistan more as it had the Indus river. While referring to India as Bharat, he asked Seth Govind Das and other Hindi speakers to rename the Hindi language ‘Bharati’, for the goddess of learning. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Ram Sahai supported the name Bharat, saying the union of Gwalior, Indore and Malwa called itself Madhya Bharat and “in all our religious scriptures and all Hindi literature this country has been called Bharat, our leaders also refer to this country as Bharat in their speeches”. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Then Kamalapati Tripathi gave a rousing speech saying that “Bharat, that is India” might have been more proper and in accordance with the “sentiments and prestige of the country”. He claimed that during its “slavery for one thousand years”, the country had lost its soul, history, prestige and form and name. He said Bapu’s revolutionary movement had made the nation recognise its form and lost soul, and that it was due to his penance that it was regaining its name too. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Tripathi said that the mere uttering of the word conjured up a picture of cultured life. That despite centuries of prolonged slavery, the name persisted, that “the gods have been remembering the name of this country in the heavens” and have a keen desire to be born in the sacred land of Bharat. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

“We are reminded that on the one hand, this culture reached the Mediterranean and on the other it touched the shores of the Pacific,” he claimed. It reminded one of the Rig Veda and the Upanishads, of the teachings of Krishna and the Buddha, of Shankaracharya, or Rama’s bow and Krishna’s wheel, he said.

As Tripathi rhapsodised over the past, Ambedkar asked, “Is all this necessary, sir... There is a lot of work to be done.” While Ambedkar was in a hurry, Assembly president Rajendra Prasad allowed another intervention from Hargovind Pant, who said he had suggested the name Bharat Varsha, which was “used by us in our daily religious duties while reciting the Sankalpa. Even at the time of taking our bath we say in Sanskrit, “Jamboo Dwipay, Bharata Varshe, Bharat Khande, Aryavartay, etc…It means that I so and so, of Aryavart in Bharat Khand, etc.” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Pant said Bharat was used by Kalidasa to refer to the kingdom of the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntala, whereas India was a name given by foreigners who were tempted by its wealth, and that clinging to it “would only show that we are not ashamed of having this insulting word which has been imposed on us by alien rulers.” | ||

| + | |||

| + |

The Constituent Assembly voted by show of hands with 38 ayes and 51 noes, so Kamath’s amendment was rejected and the original wording stayed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Bharat and India can be interchangeably used=== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/article-share?article=06_09_2023_030_008_cap_TOI Pradeep Thakur & Amit Anand Choudhary, TNN, Sep 6, 2023: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | New Delhi : Legal and constitutional experts said there was no illegality in the use of ‘Bharat’ in place of ‘India’ in any official communication as it was part of the Constitution that reads ‘India, that is Bharat’.

| ||

| + | |||

| + | However, they were also unanimous that a change in the Preamble to replace ‘India’ with ‘Bharat’ would require a constitutional amendment to be passed by two-thirds majority in the two Houses of Parliament and ratified by at least half of the states.

| ||

| + | At present, governments favour ‘India’ as the country’s name but it can be substituted by ‘Bharat’ by a government order that will require no ratification by Parliament. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Delving into the constitutional history and situation prevalent at the time of Independence that led to the continuing use of ‘India’, senior lawyer Rakesh Dwivedi said the intent of the Constitution framers was also to use ‘Bharat’ and, therefore, there was nothing wrong in privileging Bharat over India. However, if India was to be dropped, a constitutional amendment would be needed under Article 368, he clarified. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Former law secretary P K Malhotra concurred. “Unnecessary controversy is being raised over the use of ‘Bharat’ instead of ‘India’ in the invite by the President. Article 1 of the Constitution, which prescribes the name and territory of the Union, specifically says, ‘India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States’. In practise, we might be using ‘India’ but there is nothing which stops us from using ‘Bharat’ while describing our country,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Malhotra said there was no conflict between the two descriptions. “It is a matter of choice, and it should be our choice to use ‘Bharat’. Nothing needs to be done for using ‘Bharat’,” he said, adding that the government would be well within its rights even in issuing an order or resolution making it mandatory to use ‘Bharat’ in all official documents. | ||

| + | |||

| + |

Senior advocate Nidhesh Gupta said ‘India’ was synonymous with ‘Bharat’ and, therefore, could be used interchangeably. If ‘India’ has to be altogether deleted from the Constitution, then an amendment of the Constitution would be required, he said.

In 2016, the Supreme Court had dismissed a PIL that sought renaming ‘India’ as ‘Bharat’. “Bharat or India? You want to call it Bharat, go right ahead. Someone wants to call it India, let him call it India,” the bench comprising then Chief Justice T S Thakur and Justice U U Lalit had said. | ||

[[Category:History|IINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OF | [[Category:History|IINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OFINDIA, THE NAMES OF | ||

Latest revision as of 21:02, 4 October 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

[edit] The official name of India

See below

[edit] India, in the official languages of India

Assamese ভাৰত Bhārôt

Bengali ভারত Bhārot

Bodo भारत Bhārôt

Dogri भारत Bhārat

Gujarati ભારત Bhārat

Hindi भारत Bhārat

Kannada ಭಾರತ Bhārata

Kashmiri ہِندوستان Hindōstān

Konkani भारत Bharot

Maithili भारत Bhārat

Malayalam ഭാരതം Bhāratam

Marathi भारत Bhārat

Meitei (Manipuri) (Bengali Assamese ভারত Bharôt) ( Meitei script ꯏꯟꯗꯤꯌꯥ[D] Indiyā)

Nepali भारत Bhārat

Odia ଭାରତ Bhārata

Punjabi ਭਾਰਤ Bhārat

Sanskrit भारतम् Bhāratam

Santali (Ol Chiki ᱥᱤᱧᱚᱛ[E] Siñôt) (Devanagari भारोत Bharot)

Sindhi भारत Bhārat/ ڀارت

Tamil இந்தியா (official), பாரதம்[F][8] Intiyā, Pāratam

Telugu భారతదేశం Bhārata

Urdu ہندوستان Hindustān

[edit] The names of India in the languages of the world

Afrikaans Indië

Albanian India

Arabic الهند Al Hind

Belarusian Індыя

Bulgarian Индия

Cambodia. in ancient times knew India by the name "Suvarnabhumi," Sanskrit for the "Land of Gold" or "Golden Land."

Catalan Índia

Czech Indie

Chinese: 印度 (Yìndù) . Ancient name 天竺 (Tiānzhú) The Chinese name "Tiānzhú" means "Heavenly Land",

Danish Indien

Dutch Indië

English India

Estonian India

Farsi هندوستان Hindostan, with an o

Filipino: India

Finnish Intia

French Inde

Galician India

German Indien

Greek Ινδία

Hebrew הודו Hodu is the Biblical Hebrew name for India mentioned in the Book of Esther

Hindi भारत

Hungarian India

Icelandic Indland

Indonesian India Ancient name: Hindia

Irish An India

Italian India

Japanese インド (Indoku) Tenjiku was the ancient Japanese name for India, somewhat similar to the Chinese name. It is said that a merchant-adventurer Tokubei (1612–1692) had a lifelong ambition to visit 'Tenjiku' (the Heavenly Land). He even renamed himself Tenjiku Tokubei out of reverence for India.

Khmer ប្រទេសឥណ្ឌា bratesa Inda

Korean 인도 (Indeo)

Lao ປະເທດອິນເດຍ pathed India

Latvian Indija

Lithuanian Indija

Macedonian Индија

Malay: India

Mandarin 印度

Norwegian India

Polish Indie (Indi)

Portuguese Índia

Romanian India

Russian Индия (Indiya)

Serbian Индија

Slovak India

Slovenian Indija

Spanish India

Southeast Asia (Thailand, Malaysia, Java and Bali) Ancient name: Jambu Dwipa

Swahili Uhindi

Swedish Indien

Tagalog. Filipino Indiya

Thai อินเดีย (Indiya/ In-thi-ya )

Tibet: Ancient names:

i) Gyagar: This is the name that the people of Ladakh use to this day.

ii) བོད་ཡུལ་ (Bod-yul) The Tibetan name "Bod-yul" means "Land of the Bhoṭiya people" who live in the Himalayan area bordering Tibet and Nepal and are found in three states of India – Sikkim, West Bengal and Utarakhand. In Utarakhand, the Bhotia primarily reside in the districts of Pithoragarh, Chamoli, Almorah, Utarkashi and Nainital.

iii) Phagyul: the land of the Aryas i

Turkish Hindistan

Ukrainian Індія

Vietnamese Ấn Độ

Welsh India

[edit] The historical names of India

One of the oldest names used in association with the Indian subcontinent was Meluha that was mentioned in the texts of ancient Mesopotamia in the third millennium BCE, to refer to the Indus Valley Civilisation.

The earliest recorded name that continues to be debated is believed to be ‘Bharat’, ‘Bharata’, or ‘Bharatvarsha’, that is also one of the two names prescribed by the Indian constitution. Its roots are traced to Puranic literature, and to the Hindu epic, Mahabharata

Bharata, writes social scientist Catherine Clémentin-Ojha,, refers to the “supraregional and subcontinental territory where the Brahmanical system of society prevails”. Geographically, the Puranas mentioned Bharata to be situated between the ‘sea in the south and the abode of snow in the north’. Its shape and dimensions varied across different ancient texts. In that sense, …Yet, on another note, Bharata is also believed to be the mythical founder of the race.

‘Aryavarta’, as mentioned in the Manusmriti, referred to the land occupied by the Indo-Aryans in the space between the Himalayas in the north and the Vindhya mountain ranges in the south.

The name ‘Jambudvipa’ or the ‘land of the Jamun trees’ has also appeared in several Vedic texts, and is still used in a few Southeast Asian countries to describe the Indian subcontinent.

Jain literature on the other hand, also lays claim to the name Bharat, but believes that the country was called ‘Nabhivarsa’ before. “King Nabhi was the father of Rishabhanatha (the first tirthankara) and grandfather of Bharata,” writes geographer Anu Kapur in her book, ‘Mapping place names of India’.

The name ‘Hindustan’ was the first instance of a nomenclature having political undertones. It was first used when the Persians occupied the Indus valley in the seventh century BCE. Hindu was the Persianised version of the Sanskrit Sindhu, or the Indus river, and was used to identify the lower Indus basin. From the first century of the Christian era, the Persian suffix, ‘stan’ was applied to form the name ‘Hindustan’.

At the same time, the Greeks who had acquired knowledge of ‘Hind’ from the Persians, transliterated it as ‘Indus’, and by the time the Macedonian ruler Alexander invaded India in the third century BCE, ‘India’ had come to be identified with the region beyond the Indus.

By the 16th century, the name ‘Hindustan’ was used by most South Asians to describe their homeland. Historian Ian J. Barrow in his article, ‘From Hindustan to India: Naming change in changing names’, writes that “in the mid-to-late eighteenth century, Hindustan often referred to the territories of the Mughal emperor, which comprised much of South Asia.” However, from the late 18th century onwards, British maps increasingly began using the term ‘India’, and ‘Hindustan’ started to lose its association with all of South Asia…

[edit] The debate to name an Independent India

After the Independence of the country, the Constituent Assembly set up a drafting committee under the chairmanship of B R Ambedkar on August 29, 1947. However, the section, ‘name and territory of the Union’ was taken up for discussion only on September 17, 1949. Right from the moment the first article was read out as ‘India, that is Bharat shall be a union of states’, a division arose among the delegates.

Hari Vishnu Kamath, a member of the Forward Bloc suggested that the first article be replaced as ‘Bharat, or in the English language, India, shall be and such.’ Seth Govind Das, representing the Central Provinces and Berar, on the other hand, proposed: “Bharat known as India also in foreign countries”. Hargovind Pant, who represented the hill districts of the United Provinces, made it clear that the people of Northern India, ‘wanted Bharatvarsha and nothing else’…

It is worth noting though, that ‘Hindustan’ was hardly a contender in the debates. “Hindustan received different treatments during the constituent assembly,” writes Ojha. She adds that “three names had been at the start of the race, but at the end two had been placed on equal footing and one dropped.”…

[edit] The word India

The Avestan name for Sindh is Hinduš. It was inscribed by Persian emperor Darius I (550-486 BC) on the Persepolis terrace

The ancient Greeks used the name Ἰνδία (Indía). Herodotus (484 – 425/413 BC) referred to "Indian land" Ἰνδός/ Indos (‘an Indian’), following the Persians. This was more than 1300 years before the word was used in the English language.

The Byzantine people used the word Iindía to describe the region beyond the Indus (Ἰνδός) River

Ancient Latin speakers borrowed the name India from the Greeks.

Most European languages—including English—use a variant of the Latin word India.

In English, King Alfred (A.D. 848-899)'s translation of Orosius is the oldest known use of the word India in the English language. this was more than 1300 years after the earliest recorded use of the word.

However, English writers who were influenced by the French replaced India with Ynde and Inde. Inde remains the French spelling to this day.

William Shakespeare (1564- 1616) and the first edition of the King James Bible (1611) used the spelling Indie

In the 1600s the Spanish and the Portuguese spelt the word as it is today, India, which was also the official Latin spelling. This could have induced the British to revert to the spelling India.

Summary: The British did not coin the name India. Latin- speakers did. They in turn took it from the Greeks, who were influenced by the Persians, who preceded the oldest known British use of the word India by more than 1300 years

The name India has nothing to do with the colonial era and is the name by which India has been known to its Western neighbours for the last 2500 years or even more.

[edit] Kling, in the Malay and neighbouring languages

The term "Kling" is a Malay word that was used to refer to people from the Kalinga kingdom, which was located in what is now the Indian state of Orissa. The Kalinga kingdom was a powerful empire that existed from the 3rd century BC to the 13th century AD. It was known for its wealth and its military prowess.

The term "Kling" was first used in Southeast Asia in the 14th century, when the Kalinga kingdom was in decline. The Malays began to use the term to refer to all Indians, regardless of their origin. This usage of the term was not derogatory at the time. In fact, it was often used as a term of respect.

However, the meaning of the term "Kling" began to change in the 19th century. As more and more Indians migrated to Southeast Asia the term "Kling" came to be used as a derogatory term for Indians, and it is still considered offensive by many Indians today.

[edit] B

[edit] THE LEGAL, CONSTITUTIONAL POSITION IN INDIA

[edit] Name: India, not Hindustan

[edit] 1947, June

June 18, 2022: The Times of India

From: June 18, 2022: The Times of India

A quick recap of June 1-10: After hectic parleys through March-April and again in late May and early June, the basic plan for partition is announced simultaneously in Delhi and London on June 3. The Hindu Mahasabha rejects the plan and calls for more land to be ceded to India. The shape of the nation hasn’t been finalised. Almost half a billion people wait for the details to emerge.

June 11-18: Picking a name, dividing the army

“Caste Hindus on trial”: On June 12, at his daily post-prayer meeting, Mahatma Gandhi says that even though the Muslim-majority areas want to call their part Pakistan, there is no need to call the rest of the territory Hindustan.

He asks, would Hindustan mean “the abode of the Hindus”? What of the Parsis, Christians and Jews born in India, and the “Anglo-Indians who did not happen to have white skins” – did they have any home other than India?

A front-page report quotes Gandhi saying, "History has shown that the possessors of proud names did not make the possessors great. Men and groups were known not by what they called themselves but by their deeds... That's why Nehru loved to call it by the proud name of the 'Union of Indian republics', from which some Muslim-majority areas had seceded."

Gandhi puts a challenge to what he calls ‘caste Hindus’: "Already the taunt is being levelled against the Union that the much-maligned caste Hindus would ostracise the millions of Scheduled Classes, and an equal number of Shudras and the so-called aboriginal tribes… Caste Hindus are on trial. Would they recognise and do their obvious duty, and give place to the least in the Union by affording them all the facilities to rise to the highest status?" Patel puts weight behind Partition plan: Sardar Patel tells a session of the All-India Congress Committee (AICC) that no one wants partition, but the reality is stark and undeniable.

He denies that the Congress Working Committee had accepted the plan out of fear and tells Congressmen not to "give way to emotionalism and sentimentality". He says the choice is essentially between one division or many divisions.

The report quotes him indirectly mentioning those who had laid their lives for independence, "They worked for independence, and they should see as large a part of this country as possible become free and strong. Otherwise, there would be neither 'Akhand Hindustan' nor Pakistan."

After a series of speeches by leaders, 157 out of 218 AICC members endorse the partition in a vote on June 15, with 29 votes against. Five hundred reporters and other visitors crammed into the Constitution Club, with many more squatting on the lawns outside, receive the result in silence.

No to dividing armed forces on communal lines: Both the Congress and Muslim League – the main members of the High-Power Partition Committee – are for dividing the armed forces along territorial lines, and not communal ones, says a June 12 report in the TOI.

An expert committee is being drawn up to decide the details. The full handover of the forces might spill over beyond June 1948, by when the British want to withdraw, because of the time-consuming effort and the lack of trained personnel.

Noting that almost every battalion has a mix of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and other communities, the TOI reports notes that “they have separate kitchens”.

An unnamed high-ranking officer at the general headquarters quotes a poll conducted in the three army commands in the North, South and East that showed that 95% of the soldiers wanted common kitchens. Hyderabad and Travancore want independence, Gandhi calls it ‘war’: Calling Hindus and Muslims "the two eyes" of his dominion and promising to foster cordial relations between them, the Nizam of Hyderabad puts out a firman or edict stating his wish for Hyderabad to remain a sovereign state.

Mir Osman Ali says he wants to join neither of the two new nations being created. Chithira Thirunal, the Maharaja of Travancore, joins him in declaring he wants to stay independent.

Gandhi exhorts the states to join India. He says it is "amazing and wholly unworthy of any state" to be happy to stay in a British India but refuse to join the independent nation.

Gandhi ramps up pressure through the week, writing two days later, "The states' decision is tantamount to declaring war against the free millions in India. Such a thing is inconceivable, especially when the prince has no backing from the people of his state. The audacity of such a declaration is amazing."

Meanwhile in the rest of India

Foodgrains crisis in Bombay: Dinkarrao Desai, minister for civil supplies in Bombay, says that the state’s stocks of wheat and rice are precariously low.

He says the province’s monthly demand for wheat is 35,000 tonnes, but it is unlikely to get more than 10,000-12,000 tonnes. The scarcity would last at least three more months from June, Desai warns a public meeting in Girgaum.

“Our wheat crop has failed completely on account of rust and the crops in the Central Provinces and the United Provinces have also been partly affected,” he reports.

How India lived: Advertisements in TOI

Ghanshyam Das Birla's Hindustan Motors imported and serviced American Studebaker vehicles in 1947 before signing an agreement with them in 1948 to assemble the cars in Uttarpara, West Bengal.

In 1950, India produced about 40% of the world's tea, more than two-thirds of which was exported. The challenge for tea companies in India through the 1930s and 1940s was to expand the Indian market.

Milan , a film starring Dilip Kumar and Ranjana that opened during the week, was an adaptation of Rabindranath Tagore's story Noukadubi ( The Wreck ). It was Dilip Kumar's first film for Devika Rani’s Bombay Talkies studio.

[edit] Bharat In the constitution

Sep 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Sep 6, 2023: The Times of India

The name ‘Bharat’ wasn’t there in the first draft of India’s Constitution introduced by the chairman of the drafting committee, BR Ambedkar, on November 4, 1948. Although some members flagged the omission of a native name, the debate on this took place almost a year later when the work on finalising the text was coming to an end.

On September 18, 1949, Ambedkar moved the following amendment to draft Article 1, which mentions the country’s name: “India, that is, Bharat shall be a Union of States.” But Assembly member HV Kamath said this was a clumsy construction and a constitutional slip. He suggested two alternatives: “Bharat, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States” or “Hind, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States”.

Kamath cited the example of Ireland: “The name of the State is Eire, or, in the English language, Ireland.” He wanted to specify “in the English language, India” because in many other countries India was still known as ‘Hindustan’, “and all natives of this country are referred to as Hindus, whatever their religion may be…” Asked to pick one name for his amendment, Kamath chose “Bharat, or, in the English language, India, shall be a Union of States.”

Then followed an intense debate in which members Seth Govind Das, Kamalapathi Tripathi, Kallur Subba Rao, Ram Sahai and Har Govind Pant passionately argued for Bharat. Das said India was not an ancient word and was not found in the Vedas. It was only used after the Greeks came to India, while Bharat was to be found in the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Brahmanas, the Mahabharata and the Puranas, as well as in Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang’s writing.

Das suggested “Bharat known as India also in foreign countries”. He said the name was not backward-looking but befitted India’s history and culture. “If we do not arrive at correct decisions in regard to these matters the people of this country will not understand the significance of self-government.”

Kallur Subba Rao said the name India came from Sindhu or Indus, and the name Hindustan suited Pakistan more as it had the Indus river. While referring to India as Bharat, he asked Seth Govind Das and other Hindi speakers to rename the Hindi language ‘Bharati’, for the goddess of learning.

Ram Sahai supported the name Bharat, saying the union of Gwalior, Indore and Malwa called itself Madhya Bharat and “in all our religious scriptures and all Hindi literature this country has been called Bharat, our leaders also refer to this country as Bharat in their speeches”.

Then Kamalapati Tripathi gave a rousing speech saying that “Bharat, that is India” might have been more proper and in accordance with the “sentiments and prestige of the country”. He claimed that during its “slavery for one thousand years”, the country had lost its soul, history, prestige and form and name. He said Bapu’s revolutionary movement had made the nation recognise its form and lost soul, and that it was due to his penance that it was regaining its name too.

Tripathi said that the mere uttering of the word conjured up a picture of cultured life. That despite centuries of prolonged slavery, the name persisted, that “the gods have been remembering the name of this country in the heavens” and have a keen desire to be born in the sacred land of Bharat.

“We are reminded that on the one hand, this culture reached the Mediterranean and on the other it touched the shores of the Pacific,” he claimed. It reminded one of the Rig Veda and the Upanishads, of the teachings of Krishna and the Buddha, of Shankaracharya, or Rama’s bow and Krishna’s wheel, he said. As Tripathi rhapsodised over the past, Ambedkar asked, “Is all this necessary, sir... There is a lot of work to be done.” While Ambedkar was in a hurry, Assembly president Rajendra Prasad allowed another intervention from Hargovind Pant, who said he had suggested the name Bharat Varsha, which was “used by us in our daily religious duties while reciting the Sankalpa. Even at the time of taking our bath we say in Sanskrit, “Jamboo Dwipay, Bharata Varshe, Bharat Khande, Aryavartay, etc…It means that I so and so, of Aryavart in Bharat Khand, etc.”

Pant said Bharat was used by Kalidasa to refer to the kingdom of the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntala, whereas India was a name given by foreigners who were tempted by its wealth, and that clinging to it “would only show that we are not ashamed of having this insulting word which has been imposed on us by alien rulers.”

The Constituent Assembly voted by show of hands with 38 ayes and 51 noes, so Kamath’s amendment was rejected and the original wording stayed.

[edit] Bharat and India can be interchangeably used

Pradeep Thakur & Amit Anand Choudhary, TNN, Sep 6, 2023: The Times of India

New Delhi : Legal and constitutional experts said there was no illegality in the use of ‘Bharat’ in place of ‘India’ in any official communication as it was part of the Constitution that reads ‘India, that is Bharat’.

However, they were also unanimous that a change in the Preamble to replace ‘India’ with ‘Bharat’ would require a constitutional amendment to be passed by two-thirds majority in the two Houses of Parliament and ratified by at least half of the states. At present, governments favour ‘India’ as the country’s name but it can be substituted by ‘Bharat’ by a government order that will require no ratification by Parliament.

Delving into the constitutional history and situation prevalent at the time of Independence that led to the continuing use of ‘India’, senior lawyer Rakesh Dwivedi said the intent of the Constitution framers was also to use ‘Bharat’ and, therefore, there was nothing wrong in privileging Bharat over India. However, if India was to be dropped, a constitutional amendment would be needed under Article 368, he clarified.

Former law secretary P K Malhotra concurred. “Unnecessary controversy is being raised over the use of ‘Bharat’ instead of ‘India’ in the invite by the President. Article 1 of the Constitution, which prescribes the name and territory of the Union, specifically says, ‘India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States’. In practise, we might be using ‘India’ but there is nothing which stops us from using ‘Bharat’ while describing our country,” he said.

Malhotra said there was no conflict between the two descriptions. “It is a matter of choice, and it should be our choice to use ‘Bharat’. Nothing needs to be done for using ‘Bharat’,” he said, adding that the government would be well within its rights even in issuing an order or resolution making it mandatory to use ‘Bharat’ in all official documents.

Senior advocate Nidhesh Gupta said ‘India’ was synonymous with ‘Bharat’ and, therefore, could be used interchangeably. If ‘India’ has to be altogether deleted from the Constitution, then an amendment of the Constitution would be required, he said. In 2016, the Supreme Court had dismissed a PIL that sought renaming ‘India’ as ‘Bharat’. “Bharat or India? You want to call it Bharat, go right ahead. Someone wants to call it India, let him call it India,” the bench comprising then Chief Justice T S Thakur and Justice U U Lalit had said.

[edit] Attempts to rename the country

[edit] 1949 – 2020

Apurva Vishwanath, Sep 6, 2023: The Indian Express

From Constituent Assembly debates to interventions in the Supreme Court, using the name Bharat over India has been a fraught issue.

It was on September 18, 1949, that draft Article 1 of the Constitution, which refers to the Union of States as “India, that is, Bharat” was formally adopted by the Constituent Assembly. From the placing of the two commas, the order of the words to an express mention that India is English for Bharat — the issue was fiercely debated by the framers of the Constitution before settling on Article 1.

While adopting the provision, H V Kamath had moved an amendment underlining the use of Bharat. Indeed, he called for the use of a “much happier expression” that “Bharat, or, in the English language, India, shall, be and such.” However, the amendment was not passed.

Apart from Article 1, the Constitution, originally drafted in English does not refer to “Bharat” in any other provision. The Preamble also refers to “We the People of India.”

In 2020, Chief Justice of India S A Bobde dismissed a PIL seeking a name change. “Bharat and India are both names given in the Constitution. India is already called ‘Bharat’ in the Constitution,” Justice Bobde had said refusing to hear the plea.

In 2015, the BJP-led Centre had told the Supreme Court, in response to a PIL calling for a name change, that there was “no change in circumstances since the Constituent Assembly debated the issue to warrant a review.”

It said that the issues regarding the country’s name were deliberated upon extensively by the Constituent Assembly when the Constitution was drafted and clauses in Article 1 were adopted unanimously. It also pointed out that Bharat did not figure in the original draft of the Constitution and it was during debates that the Constituent Assembly considered names and formulations such as Bharat, Bharatbhumi, Bharatvarsh, India that is Bharat, and Bharat that is India.

The affidavit by the Ministry of Home Affairs was filed after a petitioner made a representation to the Centre.

The SC then dismissed the plea.

In 2004, the Uttar Pradesh Assembly passed a resolution that the Constitution must be amended to say “Bharat, that is India,” instead of “India, that is Bharat.” While then Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav moved the resolution, it was adopted unanimously when the Bharatiya Janata Party, which was in then in the opposition, walked out before the resolution was passed.

The names of villages, towns, railway stations etc are changed under revenue laws of the state since “land” falls in the state list of the Seventh Schedule.

However, the name change requires the approval of the Union Home Ministry after which the state government issues a notification in the official gazette. For renaming states, a change in the Constitution is required.

Articles 2 & 3 of the Constitution which list out the names of the states in the Union can be changed with a simple majority. In 2011, Orissa was renamed Odisha; in 2007, Uttaranchal was renamed Uttarakhand; in 1973, Mysore was renamed Karnataka and in 1969, Madras state was renamed Tamil Nadu.

However, in Tamil Nadu and Odisha, the High Courts have continued to retain the old names of the state.

[edit] Jinnah, Pakistan deny Bharat the names ‘India,’ ‘Hindustan’

Arjun Sengupta, Sep 8, 2023: The Indian Express

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, always wanted the new Muslim homeland to be called Pakistan, the “land of the pure”. Even though Pakistan would be carved out of the original India, he did not want the name of the new country to have anything to do with ‘India’.

“No tussle over the word ‘India’ is reported because Jinnah preferred the newly coined and very Islamic-sounding acronym that is ‘Pakistan’,” historian John Keay wrote in India: A History (Harper Press, 2000).

The term ‘Pakistan’ was coined by Choudhary Rehmat Ali in 1933, and was actually an acronym for the five northern provinces of India — Punjab (P), North-West Frontier Province or Afghan Province (A), Kashmir (K), Sindh (S) and Balochistan (‘tan’). By the time the movement for a separate Islamic state in the subcontinent picked up in the 1940s, the name became ubiquitous in Muslim League speeches and correspondence. By the time Partition became a certainty, ‘Pakistan’ was the name of the choice for the new Islamic-majority state.

However, he did not want independent India to be called ‘India’.

“He [Jinnah] was under the impression that neither state (India or Pakistan) would want to adopt the British title of ‘India’. He only discovered his mistake after Lord Mountbatten, the last British viceroy, had already acceded to Nehru’s demand that his state remain ‘India’. Jinnah, according to Mountbatten, was absolutely furious when he found out,” Keay wrote.

Jinnah had a persistent insecurity about India, both about the new nation and its name.

In his paper ‘Islam and the Constitutional Foundations of Pakistan’, Martin Lau, professor of South Asian law at SOAS, quoted from a letter Jinnah wrote to India’s first Governor General Lord Mountbatten, complaining that the name ‘India’ is “misleading and intended to create confusion”. (Lau in ‘Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries: Between Upheaval and Continuity’, eds. Rainer Grote and Tilmann Röder, Oxford University Press, 2012).

Jinnah was never really happy with how the Partition panned out. Despite the Muslim League’s claims, Pakistan received far less land than expected. For Jinnah, there was a very real danger of Pakistan becoming subordinate to India. His views on the term ‘India’ flowed from the same fears.

“The use of the word implied a subcontinental primacy which Pakistan would never accept,” John Keay wrote.

Moreover, the etymological origin of the term ‘India’ referred to lands that, post-Partition, primarily lay on Pakistan’s side of the border. For a nascent nation state that no one had even imagined even 15 years earlier, laying claim to this “history” (or at least not letting ‘Hindustan’ claim it) was paramount.

“It also flew in the face of history, since ‘India’ originally referred exclusively to territory in the vicinity of the Indus river (with which the word is cognate). Hence it was largely outside the republic of India but largely within Pakistan,” Keay wrote. Lastly, Jinnah wanted India to take the name of ‘Hindustan’ to make clear the religious bases for the Partition and consequently, the new nation states. But as Lau observes in a footnote, “the provisions of the Indian Independence Act did not make Pakistan an Islamic states … nor did the Indian Independence Act of 1947 make India a Hindu Raj”.

What “had convinced Jinnah that neither side would use it [India],” Keay wrote, “stemmed from its historical currency amongst outsiders, especially outsiders who had designs on the place.” Jinnah felt that the term ‘India’, carried with it, the baggage of being an “object of conquest”, something that would dissuade Nehru from laying claim to it.

Jinnah protested, but to no avail.

Close to the end of her book The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (Cambridge University Press, 1985), the Pakistani-American historian Ayesha Jalal of Tufts University noted in passing that “until the bitter end the [Muslim] League continued to protest against Hindustan adopting the title ‘Union of India’”, which, she said, could be seen as “a commentary…that Jinnah never quite abandoned his strategy of bringing about an eventual union of India on the basis of Pakistan and Hindustan”. “Jinah’s irritation at the fact that the new Dominion of India was not called “Hindustan” (the land of the Hindus), became visible in an exchange of letters with…Mountbatten,” Lau wrote.

“In September 1947, Mountbatten invited Jinah to become the honorary president of an exhibition of Indian art in London. Its announcement was to include the explanation that “the Exhibition includes exhibits from the dominions of India and Pakistan”,” Lau wrote.

According to him, “Jinah rejected the invitation” because of the use of the name ‘India’, writing to Mountbatten that, “It is a pity that for some mysterious reason Hindustan have adopted the word “India” which is certainly misleading and is intended to create confusion”. He suggested that in order to avoid misleading people, the description should read “exhibition of Pakistan and Hindustan art”.

“This”, Lau said, “proved unacceptable to Mountbatten, and in the end Jinah accepted the invitation”. (Jinnah Papers (n 50) Vol. 5, 358)

Two years later, in September 1949, when the Constituent Assembly of India began to discuss the draft Constitution of India, the name “Hindustan” was also on the table, but was quickly rejected. Article 1 of the Constitution uses “India” and “Bharat” interchangeably in its English version, and “Bharat” is used in the Hindi version.