Elephants: India

(→Man- elephant conflict) |

(→Details) |

||

| Line 567: | Line 567: | ||

In five case studies in north Bengal, herd members dragged the calves away from human settlements before burying them in “leg-upright position” in irrigation trenches inside tea gardens. |

In five case studies in north Bengal, herd members dragged the calves away from human settlements before burying them in “leg-upright position” in irrigation trenches inside tea gardens. | ||

| − | ==Details== | + | ===Details=== |

''' ‘Jumbos avoid paths where carcasses of calves are buried’ ''' | ''' ‘Jumbos avoid paths where carcasses of calves are buried’ ''' | ||

| Line 585: | Line 585: | ||

ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:Pages with broken file links|ELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIA | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIA | ||

| + | ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Fauna|E ELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIA | ||

| + | ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|E ELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIA | ||

| + | ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIAELEPHANTS: INDIA | ||

ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ELEPHANTS: INDIA]] | ||

Revision as of 22:35, 5 March 2024

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Population, state-wise

2014-16

From: The Times of India, Feb 11, 2017

See graphic:

State and population of wild elephants, 2014-16

2017: population stable

See graphic: States with highest elephant population, 2017

India's elephant habitat has expanded, with the jumbo population “stable“ at 27,000, according to a census of the animals released by the Union ministry of environment, forests and climate change, World Elephant Day .

The report, `Synchronised elephant population estimation India 2017', pegs the exact population of jumbos at 27,312, with Karnataka accounting for the biggest share followed by Assam.

The figures show a decline in the overall population, from 29,391-30,711 in 2012, but this has been attributed to a difference in the counting methods used.

“There is no question of a decline,“ said elephant expert and head of Asian Nature Conservation Foundation R Sukumar. Experts termed the “expansion“ trend worrying because it could lead to an increase in human-animal conflicts.

Assam

2017 population in Assam, NE, other states

From: Naresh Mitra, Nov 7, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Elephant population in Assam, NE, other states, 2017

Kaziranga National Park

The Times of India, Aug 17, 2016

Rohit Khanna & Prabin Kalita

'Bangabahadur' of Assam dies in Bangladesh

A wild elephant, which had got separated from its herd in Kaziranga National Park in June and which was swept away by the Brahmaputra to Bangladesh, died despite all efforts to save her. The adult female elephant, named Bangabahadur (hero of Bengal) by locals in Bangladesh, was first spotted in Kurigram district in that country. It travelled further downstream through Bogra and Sirajganj districts before finally washing up in Jamalpur district in the third week of July. On August 3, a three-member team from Assam travelled to the neighbouring country to bring back the animal but the plan was abandoned and it was decided that the jumbo would be relocated to a safari park in Bangladesh. On August 11, the elephant was rescued from a pond in Kayra village in Sharishabari being being tranquillized thrice. Bangladesh media quoted officials as saying the elephant was 'too weak and tired'.

The animal died at around 6:30 am in Kayra, Bangladesh media reported. "Bangabahadur was becoming restless so we had to give him tranquiliser. It was a very measured dosage, but we could not determine that his health conditions had deteriorated so much," said Tapan Dey, deputy chief conservator of forests of Bangladesh forest department. According to him, Bangabahadur was gradually becoming weaker as he was out of his usual habitat.

"It seems that he had swept through the river for around 1,000 kms. This has not only weakened the elephant, but taken a toll on his overall health. We suspect that the elephant was also suffering from pneumonia," said Dey. He added that Bangabahadur was kept chained but started becoming restless since Sunday afternoon. "He refused to eat and tried to break the chains on Sunday. We decided to keep him under sedation and he was injected with tranquiliser," Dey said. Accordingly, measured dosages of tranquiliser was injected. But scorching heat, coupled with weakness, was deteriorating his condition faster. According to Hasibur Reza Kallol, treasurer of Bangladesh-based NGO People for Animal Welfare, the situation could have been avoided if there was no pressure to send it back to India. "It was entirely a new habitat for the elephant and it needed time to acclimatize. More time to get him habituated with the new ambience could have saved his life," he said.

Karnataka

Manchanabele Reservoir

The Hindu, November 6, 2016

MOHIT M. RAO

Jumbo question: Life or death for ailing Sidda?

Although euthanasia is legal for animals, public pressure has made the decision nearly impossible. The narrow, uneven and dusty road that skirts the sprawling Manchanabele Reservoir in Karnataka has seen unusually busy traffic. The attraction is Sidda, a 35-year-old elephant, which has, since its injury, been confined to the banks of the reservoir for 57 days.

Just one leg seems to have the energy to undertake a futile attempt at scooping muck across its immense, heaving torso; while its trunk lugubriously rolls around towards puddles of water. The foreleg is visibly swollen as its wound festers. Behind it, the Forest Department has set up a camp with at least eight personnel, including veterinarians. In shifts, they spray water on Sidda to keep it cool on warm days.

On August 30, 2016, while being chased by villagers on the outskirts of Bengaluru, Sidda fell into a ditch. It was given treatment and escorted back to the Savandurga Reserve Forest. However, crippled with severe pain, on September 11, the elephant was spotted again floating in the backwaters of the reservoir. Its condition deteriorated and, for the past fortnight, it has been recumbent and immobile. The list of ailments is long: compound fracture, septicemia, partial blindness, dehydration, swelling of the leg and anaemia.

‘Let nature decide’

Officials say public pressure has made the decision nearly impossible and they would now “let nature decide.”

One self-proclaimed animal rights activist from the United States has threatened to cancel her donation to an NGO if it does not euthanise. “You chose to take credit for “helping” Sidda and to bask in the glory... and now there is no glory for Sidda and there is no comfort for him as he lies dying a horrible, painful death,” she says in her online post.

However, Arun A. Sha, veterinary officer of the NGO Wildlife SOS treating Sidda, says it is premature to think of euthanasia. “It is still showing traits of a wild elephant and moving its trunk and hind leg. It is in pain, but we are providing pain killers…We have just received permission to make an apparatus that can help to shift the weight from the fore leg. If we prop up Sidda, he can perhaps recover better,” he says.

“We will continue to treat the elephant the best that we can…If only experts decide on euthanasia, we can form a committee to look into it,” says Dileep Kumar Das, Chief Conservator of Forests (Project Elephant).

The idea, however, is subsumed by community passions. “It churns our stomach to see the suffering. But euthanasia is not an option. When people are sick in the hospital, the family is ready to spend lakhs on treatment. The same should be for our Sidda,” says Shivamma, from the nearby village of Dubbaguli.

Sympathy amid conflict

The irony of the love for Sidda seems to be lost in the State which sees an unending, escalating conflict between humans and elephants. In the past three years, around 105 people have been killed; while, yearly, more than 10 elephants are electrocuted or shot.

Asian Elephant Researcher Surendra Varma believes the “signals” sent out by Sidda and Ranga need to be understood if the State wants better conservation.

“There has to be understanding of the root causes of these elephants coming out of protected areas. Mitigation measures have not been up to the mark, while cropping patterns which attract elephants have not been addressed,” he says.

Kerala

Periyar Tiger Reserve (PTR)

‘Drunk' jumbos, a new menace/ 2018

After the advent of pilgrim season, members of the forest department's elephant squad - attached to Periyar Tiger Reserve (PTR) where Sabarimala hill shrine is located - are constantly on their toes. Reason: Herds of elephants are camping close to the waste dump at Nilackal, the new base camp for pilgrims before they proceed to Pamba for their holy trek.

Officials said that wild elephants were particularly attracted to the tonnes of spoiled molasses dumped in a pit here. This has now fermented after rain water entered the pit, giving the elephants a steady source of 'heady concoction, akin to wash'.

The molasses came from the warehouse of Travancore Devaswom Board (TDB), which was damaged by floods in Pamba in August. Elephants had raided the warehouse in search of molasses after the floods.

"Every night, we have herds coming to drink this because the pit was not properly covered. Elephants step into it, make an impression with their legs and have a fill when the liquid oozes in. They seem to have acquired a taste for it," said Abdul Latheef, a forest veterinary doctor attached to PTR elephant squad.

Officials fear this might create safety issues for pilgrims as the dumping spot - situated a few hundred metres away from the helipad at Nilackal - is located close to the bus station and temporary police barracks.

"Some elephants seem to have behavioural problems due to regular consumption of the liquor-like substance and are not easily scared by our tactics. There is a possibility of the herds venturing into base camp area," the official said.

Open dumping of food waste like pineapple peels and flowers at the site is also luring the elephants.

Unscientific management of solid waste and sewage is a major issue at Pamba and Nilackal, green activists said. "For sewage, they have built a tank, next to a forest region, which overflows and reaches Pamba through a stream called Kakkattaaru," said N K Sukumaran Nair of Pamba Samrakshana Samiti.

Additional district magistrate P T Abraham, who coordinates waste management and sanitation, said he was not aware of such an issue. "We are grading bio-degradable and non-biodegradable waste and are dumping only organic waste like flowers and food. This is new to me," he said.

2018/ DNA profiling of captive elephants

Aathira Perinchery, Kerala’s captive jumbos get genetic IDs, December 18, 2018: The Hindu

Move could help solve wildlife crime cases involving poaching and illegal trade

DNA profiling may be a contentious issue among humans, but for Kerala’s captive elephants, it’s a done deal. In a first for India, every one of Kerala’s captive elephants now has a unique DNA-based genetic ID. M. Radhakrishna Pillai, Director, Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology (RGCB), which was given the task of DNA fingerprinting the elephants, handed over the DNA database, prototypes of Unique Identification Cards, and a study report to the Forest Department’s Chief Wildlife Warden P.C. Kesavan on Tuesday.

Captive elephants are those that have been captured from the wild and used by humans. The Forest Department provided blood samples of captive elephants from across the State to the RGCB for DNA fingerprinting. The method is a forensic technique that makes it possible to identify individuals — people or animals — based on unique DNA characteristics called micro-satellites (DNA portions that occur repeatedly), much like fingerprints.

To conduct DNA fingerprinting, the RGCB’s teams at the Regional Facility for DNA Fingerprinting (RFDF) in Thiruvananthapuram first removed duplicate samples after cross-verification and then isolated DNA from the samples. After tests, 11 micro-satellite markers (which help isolate specific micro-satellites) and one sex marker (for gender ID) were selected, said E.V. Soniya, head of the DNA Fingerprinting Unit at the RGCB. The database covers all 519 captive elephants. “This database is now accessible to the Forest Department,” she said. The RGCB also developed a protocol to DNA fingerprint elephants using dung and tusk samples, which could help solve wildlife crimes, including poaching and illegal trade.

Unlike the microchip-based ID used so far, DNA fingerprinting provides a unique identity and is more fool-proof, said Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests Padma Mahanti.

Odisha

Marginal increase: 2015-June 2017

Satyasundar Barik, Elephant population sees marginal rise in Odisha, July 4, 2017: The Hindu

Jumbo numbers have gone up by 22 since 2015

The first ever synchronised elephant census carried out in the country’s eastern region, involving four States, has found 1,976 elephants living in different forests of Odisha.

The synchronised elephant census-2017, the results revealed that the jumbo population has gone up marginally by 22 elephants compared with 1,954 in 2015.

Direct sighting

The elephant census was carried out simultaneously in Odisha, West Bengal, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh between May 9 and 12. Apart from direct sighting, indirect estimation of elephant through dung decay rate method by using line transect technique was also deployed. The Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru carried out the census.

While the number of male elephants, which are vital for a healthy population, stood at 344, there were 1,092 females in Odisha forests. The young elephant population was estimated at 502, but the gender of 38 elephants could not be ascertained. In 2015, there were 341 male elephants.

Of 43 forest divisions where the census was carried out, elephants were found in 37 divisions. No elephant was found in Khariar, Chilika Wildlife, City Division, Koraput, Jharsuguda and Bargarh.

Odisha has three elephant reserves comprising seven sanctuaries. These were found to have 1,536 elephants or 77.73%. While 79 elephants were roaming in five other sanctuaries, 361 were sighted outside elephant reserves and sanctuaries. The highest number of 330 elephants was sighted in the core of Similipal followed by Dhenkanal with 169. Chandaka Wildlife Sanctuary, which once boasted over 80 elephants, has only one elephant. As many as 5,847 people were engaged for enumerating the jumbos in different forests.

Odisha has recorded one of the worst man-elephant conflicts in the country. Since 2013-14, 311 elephants have been killed with annual average elephant deaths estimated at over 70. During the same period, 275 humans lost their lives in elephant depredation.

Uttarakhand

Corbett and 11 other divisions

The Times of India, Aug 23 2015

Seema Sharma

1,035 elephants rule tiger bastion Corbett

For those who equated Corbett with just tigers, think again. As per the recent elephant estimation exercise conducted in Uttarakhand in June, Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR) has emerged as one of the main bastions of elephants with the presence of as many as 1,035 pachyderms being recorded in the reserve. According to the estimation exercise, the state has a total of 1,797 elephants which is an increase of 15% over the last estimate carried out in 2012, when 1,559 elephants were recorded. It is also a rise of almost 33% over the last census of 2007 when 1,346 elephants were counted.

Elaborating on the methodology used for the estimation exercise, Dinesh Aggarwal, state forest minister, told TOI, “The estimation was conducted in CTR, Rajaji Tiger Reserve and 11 territorial divisions of Shivalik, Eastern & Northern Kumaon and Bhagirathi circles covering an area of 6643.5 sq km. Methodology was based on direct synchronized counts and detailed information about each elephant sighting. about each elephant sighting.GPS coordinates were recorded and reviewed and collated at the Wildlife Institute of India.“

The steady increase in jumbo numbers comes after a 50% increase registered in tiger sightings in Corbett. Dhananjay Mohan, who headed the exercise, told TOI, “Our effort to improve the habitat conditions in Corbett has paid off. Special efforts were made to remove weeds and lantana, which helped in expanding the feeding ground for elephants.“ Another reason, according to Anil Dutt, principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife), is that Corbett has the Ramganga river, a perennial source of water, because of which the ranges situated close to it, like Dhikala and Sarpduli accounted for 242 and 193 jumbos respectively .

Accident-proneness

Electrocution

2009-2017: 461 elephants

Shiv Sahay Singh, 461 elephants electrocuted between 2009 and 2017, November 2, 2018: The Hindu

From: Shiv Sahay Singh, 461 elephants electrocuted between 2009 and 2017, November 2, 2018: The Hindu

States in the eastern and northeastern region of the country have accounted for most of these deaths.

Between August to October 2018, more than a dozen of elephants died of electrocution in the eastern and northeastern part of India, including seven in Odisha’s Dhenkanal district.

While human-elephant conflict remains a major concern for policy makers and conservationists, electrocution of elephants is turning out to be a critical area in the management of India’s elephant population.

50 deaths a year

An analysis of data pertaining to elephant deaths in India due to electrocution between 2009 and November 2017 points out that, every year, about 50 elephants have died on average due to electrocution.

A total of 461 elephant deaths due to electrocution occurred in the nine years between 2009 and November 2017.

A closer look at the data reveals that States in the eastern and northeastern region of the country have accounted for most of these deaths — in Odisha, 90 elephants died of electrocution; 70 elephants died of electrocution in Assam; 48 elephants in West Bengal; and 23 elephants in Chhattisgarh.

Karnataka, which has the highest population of elephants, has recorded the highest causalities in elephant deaths by electrocution, numbering 106. While 17 elephants died in Kerala due to electrocution, in Tamil Nadu, the number of deaths in the same period was 50. The data has been sourced from the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MOEFCC).

Right of passage

Representatives of the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), who along with the MOEFCC’s Project Elephant had come out with a publication on the right of passage in 101 elephant corridors of the country in 2017, stressed on the need for greater surveillance and protection of elephant corridors.

“There needs to be greater coordination between the Forest Department and different agencies, including the Power Department, as well as continuous monitoring of electrical wires passing through areas of elephant movement,” Upasana Ganguly, Assistant Manager, Wild Lands Division, WTI, said. Ms. Ganguly said that the publication had touched on the issue of how critical elephant corridors are for sustaining the elephant population in the country.

Explaining why the east-central and northeastern parts of the country are witnessing greater number of incidents of human-elephant conflict, well-known elephant expert and Professor, Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, Raman Sukumar, said that elephants are expanding base all across the country and moving out of forests towards agricultural areas.

“In the east-central Indian landscape, elephants are emerging in the areas where they were never seen in decades or in centuries before. For instance, there were no elephants in Chhattisgarh for centuries, and now we are witnessing human-elephant conflict there,” Dr. Sukumar said.

Different landscapes

Along with taking measures to stop illegal electrical fencing, and having proper guidelines for maintaining the height of high tension electrical wires, Dr. Sukumar said, “We need to come up with a proper zone-wise management plan for different elephant landscapes — where to allow elephants and where to restrict their movement,” he said.

According to the all-India synchronised census of elephants in 2017, their population was 27, 312. The States with the highest elephant population are Karnataka (6,049), followed by Assam (5,719) and Kerala (3,054).

2014-20

TC Sreemol, August 25, 2021: The Times of India

An RTI reply from the ministry of environment and forests to activist K Govindan Namboothiry stated that 474 elephants were electrocuted in the country from 2014 to 2020, reports TC Sreemol.

Maximum deaths were reported in 2018 at 81, while the average was 70 every year until then. As many as 65 elephants died till December 2020 —13 in Assam and 10 in West Bengal. The maximum number of deaths in these six years was reported in Assam (90), followed by Odisha (73), Tamil Nadu (68) and Karnataka (65). Kerala reported 24 elephant deaths during this period.

Forest officers said most electrocutions are a result of illegal power fencing.

2018: not all elephant corridors are safe

1987-2017: elephants killed in train accidents

From: Radheyshyam Jadhav & Atul Sethi, (With inputs from Shivani Azad, Saugata Ghosh Dastidar, Krishnendu Mukherjee & Rajesh Sharma), Indian elephants stuck in corridors of death, October 30, 2018: The Times of India

Carcasses of seven jumbos that died of electrocution in Odisha’s Dhenkanal were found in a ditch, one of the worst accidents of its kind in recent times. But more than 100 elephants in search of passage are killed in India every year. Also lost are 400-450 lives as a result of man-animal conflict

Passengers of the Dehradun-Kathgodam Express were barely aware that their train had committed murder. Shortly past midnight on June 25 this year, the express train, travelling at a speed of around 70 km/hr, hit a female elephant that was part of a herd of 17 jumbos that was crossing the track in the Motichur area of Rajaji Tiger Reserve in Haridwar in Uttarakhand. The 35-year-old elephant died on the spot.

In a similar incident last month in West Bengal, three elephants, including a calf, were mowed down by the Gyaneshwari Express near Gidhni railway station, around 180 km from Kolkata. Last year in December, in what was described as “an elephant massacre”, the Guwahati-Naharlagun Express ran over five elephants, one of them pregnant, near the Bamgaon elephant corridor in Assam, resulting in their immediate death.

Such instances — occurring with alarming regularity — point to the spiralling man-elephant conflict, triggered primarily by shrinking space for the smooth movement of the pachyderms.

Elephant corridors — essentially linear patches of natural vegetation that connect two habitats — are important for jumbo movement and necessary for the herd to maintain a healthy population. However, sprouting of roads, railway lines, electricity towers, canals, and human settlements in these corridors are forcing elephants to stray from their natural paths, causing conflict situations with disastrous results for both man and animal.

According to the report, ‘Right of Passage: Elephant Corridors of India’, by the Delhi-based Wildlife Trust of India last year, an average of around 100 elephants are killed every year either due to train collisions, electrocution or road accidents. The report also adds that an estimated 400-450 people die due to confrontation with elephants each year.

Experts say that the crux of the problem lies in the fragmentation of available habitats, which has confined most elephant populations to small pockets. “Over 40% of the elephants are not part of protected areas or government forests and there are ever-increasing pressures on their habitat,” says P S Easa, former head of Kerala Forest Research Institute, Thrissur, and one of the contributors to the Wildlife Trust report. Increasing deforestation and urbanisation have further taken their toll on elephant corridors. It is estimated that currently only around 12.9% of the corridors are totally under forest cover. The figure was 24% in 2005.

The issue of shrinking space for elephants was also raised in Lok Sabha last month. Asked what was being done about the problem, the environment ministry had said: “(T)he central and state governments are taking various steps such as afforestation, reforestation and habitat restoration... assistance is also being provided under the centrally sponsored scheme, ‘Project Elephant’.”

Experts, however, say that much more needs to be done. “There should be management plans for elephant reserves irrespective of state or administrative boundaries. Conservation efforts should be focused mostly on consolidating habitat,” says Easa. From time to time, the issue has caught the eye of the judiciary as well, which has delivered strict orders on elephant movement.

On August 9, for instance, in response to a PIL, the Supreme Court ordered the Tamil Nadu government to close down within 48 hours, 39 hotels and resorts constructed in an elephant corridor in Nilgiri Hills.

Initiative has been taken at the community-level, too. In 2015, for example, 19 families in Ram Terang village in Karbi Anglong district of Assam voluntarily vacated their village to allow unhindered movement of elephants to and from Kaziranga National Park, a gesture lauded by Britain’s Prince William and his wife Kate Middleton during a visit to the area.

Elephant corridors

The Nilgiris: SC order of 2020

Dhananjay Mahapatra, October 15, 2020: The Times of India

Describing elephants as “keystone species” for survival of Indian forests and other animals, the Supreme Court on Wednesday concurred with the Madras high court and directed eviction of 39 resorts in the Mudumalai reserve forest area falling in the elephant corridor. The resorts, which house 309 buildings, hindered the nomadic lifestyle intrinsic to the survival of pachyderms.

A bench of Chief Justice S A Bobde and Justices S Abdul Nazeer and Sanjiv Khanna upheld the Tamil Nadu government’s order of January 1, 2010, identifying elephant corridors in the Sigur Plateau connecting the forests in the Wester n and Easter n Ghats, which sustain elephant populations and their genetic diversity.

Writing the judgment, Justice Nazeer said, “The precautionary principle makes it mandatory for the state government to anticipate, prevent and attack the causes of environmental degradation... we have no hesitation in holding that in order to protect the elephant population in the Sigur Plateau region, it was necessary and appropriate for it to limit commercial activity in the areas falling within the elephant corridor.”

The bench noticed variance in the areas to be freed of encroachments to provide unhindered passage to migrating elephants and appointed a three-member committee to identify areas for securing the corridors.

Corridors crucial in sustaining wildlife: SC

The panel will be headed by retired Madras HC judge K Venkatraman. Its other members are Ajay Desai, consultant to World Wide Fund for Nature-India, and Praveen Bhargava, trustee of Wildlife First. The committee will decide the individual objections of the appellants and others claiming to be aggrieved by the actions of the Nilgiris district collector pursuant to the TN government order and action taken reports, as also the allegations regarding arbitrary variance in acreage of the elephant corridors under the impugned order of January 2010. The bench agreed with wildlife experts’ unanimous opinion regarding elephants as a “keystone species” because of their nomadic behaviour, which is immensely important to the environment.

“The corridors allow elephants to continue their nomadic mode of survival, despite shrinking forest cover, by facilitating travel between distinct forest habitats. Corridors are narrow and linear patches of forest which establish and facilitate connectivity across habitats. In the context of today’s world, where habitat fragmentation has become increasingly common, these corridors play a crucial role in sustaining wildlife by reducing the impact of habitat isolations. In their absence, elephants would be unable to move freely, which would in turn affect many other species and the ecosystem balance of several wild habitats would be unalterably upset,” the bench said.

Any hindrance to such corridors would eventually lead to local extinction of elephants, a species which is widely revered in India and across the world, the court said. “To secure wild elephants’ future, it is essential that we ensure their uninterrupted movement between different forest habitats. For this, elephant corridors must be protected,” it added. The issue in contention before the court was the corridor in Sigur Plateau, which has the Nilgiri Hills on its south-western side and the Moyar River Valley on its north-eastern side.

2018: Chittoor-Bengaluru highway at Moghili ghat of Palamaner range

K. UMASHANKERCHITTOOR, It’s a jumbo problem on Chittoor-Bengaluru road, May 20, 2018: The Hindu

From: K. UMASHANKERCHITTOOR, It’s a jumbo problem on Chittoor-Bengaluru road, May 20, 2018: The Hindu

A herd of wild elephants criss-crossing the Chittoor-Bengaluru national highway at Moghili ghat of Palamaner range during the last three days is giving tense moments to the forest officials, who have cautioned the highway riders to move carefully and avoid encounters with the pachyderms.

The stretch of the NH at Moghili ghat section, covering the Jagamarla forest beat, is considered the favourite haunt of wild elephants during summer, as they visit some ponds here, which hold sufficient water.

According to officials, the animals cross the NH at three points in search of water. On Friday afternoon, a herd of three elephants was seen moving close to the NH, drawing the attention of some highway riders. The vehicular traffic which came to a halt for a while, resumed after the arrival of the forest officials from Chittoor and Palamaner. A batch of forest watchers was posted at the ghat section to monitor the movements of the elephants.

Divisional Forest Officer (Chittoor-West) T. Chakrapani, who is supervising the operation to facilitate the smooth movement of the wild elephants, told The Hindu that there are 35 wild elephants that frequent the Moghili ghat section. “As the NH passes through the reserve forest and the protected Koundinya elephant sanctuary, the stretch forms the natural corridor of the wild elephants,” he said.

Hospitals for elephants

2018: Farah block gets the first

There was much anticipation among the 25-odd people who had gathered at the inauguration of a state-of-the-art hospital in Farah block of Mathura. It had, however, less to do with the launch of the new facility than it did with the two patients lodged there. As Phoolkali and Maya made their way to the crowds, cellphones were whipped out and cameras clicked rapidly. Not that Phoolkali and Maya were aware of the attention they were garnering, for both of them are partially blind.

It is the vision of the two rescued elephants, as well as their foot injuries, which will be treated at India’s first hospital built exclusively for elephants. For Phoolkali, 55, and Maya, 35, both of whom have spent most of their years in captivity, this is a fresh lease on life. While Maya was a circus animal, Phoolkali would often be decked out to add grandeur to religious or wedding processions. The new hospital, set up by NGO Wildlife SOS, in collaboration with UP forest department, aims to provide critical medical care to all such rescued elephants.

This is the first fullfledged hospital dedicated to treating only elephants. The hospital, with a built-up area of nearly 12,000 square feet and four veterinarians, can treat up to three elephants at a time. Besides, its state-ofthe-art laboratory features facilities like wireless digital Xray, laser treatment, dental Xray, ultrasonography, hydrotherapy, tranquillisation equipment and quarantine facility for treatment of injured elephants in distress.

Legal rights

Keeping elephant at rehab centre not illegal: HC

January 22, 2020: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: Keeping Laxmi at an elephant rehabilitation centre cannot be termed illegal or unauthorised as jungle is the natural habitat of jumbos, Delhi high court said on Monday while refusing to entertain her mahout’s plea seeking her release from alleged illegal detention.

A bench of justices Manmohan and Sangita Dhingra Sehgal said the mahout of the 47-year-old pachyderm failed to show any documentary proof to establish that he is the owner of the elephant and that she cannot live without him.

“Keeping in view the aforesaid principle and the fact that an elephant, by virtue of its natural characteristics, requires sufficient water, large area for housing as well as for walking and grazing, this court is of the opinion that jungle is the natural habitat of an elephant and the presence of elephant Laxmi in elephant rehabilitation centre cannot be termed illegal or unauthorised,” the bench said.

Laxmi’s mahout Saddam had moved the high court seeking its directions to release her from “illegal detention” at the rehabilitation centre in Haryana.

The high court further said that in case of a conflict between the rights of the elephant and the mahout, priority will have to be given to the elephant. “This court is of the view that the elephant rehabilitation centre is better suited to take care of elephant Laxmi’s needs than a mahout,” it said.

Further, allegations of cruelty while shifting the elephant cannot be decided in a habeas corpus plea, it added.

“Even if the mahout is able to establish ownership, it would not be a ground to treat the elephant as his ‘slave’ and move elephant Laxmi to an uncomfortable environment against her rights and interests. The interest of Laxmi is best served in a forest rather than in a congested city with a mahout,” the bench said.

The high court granted liberty to Saddam to apply to the elephant rehabilitation centre for visitation rights.

Advocate Wills Mathews, appearing for the petitioner, argued that Laxmi was a Delhi resident and had been regularly participating in Republic Day parades from the year 1995 to 2007.

Life expectancy

Captive elephants: 89 years in 2023

Kangkan Kalita, August 22, 2023: The Times of India

Guwahati : Bijuli Prasad had a storied life. Famed for his strength in fending off ivory smugglers and his ability to clear tea bushes, he died at the age of 89 on a sprawling tea estate in Assam’s Sonitpur. Bijuli Prasad was India’s oldest surviving captive elephant, reports Kangkan Kalita.

Rescued from the wild in the 1940s, Bijuli Prasad was sold by the family of Ranjeet Dutta, the current local MLA, to Williamson Magor & Co Ltd in the 1950s for approximately Rs 3,000 when it was still young.

Named by Philip Magor, who frequently visited from the UK, Bijuli became an integral part of Borgang tea estate in Assam’s Sonitpur district.

Man- elephant conflict

2012-16: Attacks on humans

Please see graphics, People killed by elephants, 2012-May2016, state-wise and Year and number of humans attacked by elephants in comparison with tigers, 2012-16

and Tigers: India

2013-15: Poaching in the south

The Times of India, Aug 13 2015

100 elephants killed in 2 years across south

Viju B & Oppili

Worst jumbo carnage since Veerappan run

Kunjumon has lived most of his adult life in the forests of Kerala -as a government watchman and then as a cook for poachers.That transition made little difference, he told cops. It was the killing of a baby elephant in 2014 that changed his life.In June 2015, the 62-yearold walked into a forest office and made his peace.

What emerged in the probe was a massive poaching operation for tusks (ivory) in not just Kerala, but neighbouring Tamil Nadu and Karnataka as well. Investigators in Kerala found that the gang had killed more than 20 elephants in 10 months, but forest officials told that the toll in the southern region in the past two years could be as high as 100. And this would be the gravest of periods for elephants in the south after forest brigand Veerappan was gunned down in 2004.

Investigations in the past two months point to a nexus of poachers and forest officers.Among the 40 people arrested so far is a forest range officer and a deputy range officer.They also found poachers' dens in the Vazhachal forest and at least 17 crude guns.“The officials would open the check posts for the poachers to cart away the ivory once the elephants were killed,“ said a senior vigilance official with the forest department.

In Tamil Nadu, officials found rampant poaching in Sathyamangalam and Mudumalai tiger reserves, and Bandipur in Karnataka. The mastermind, Aikaramatton Vasu, was found dead in a farmhouse in Dodamarg in Maharashtra. There was a suicide note as well.

2014-17: Decreasing trend of human lives lost

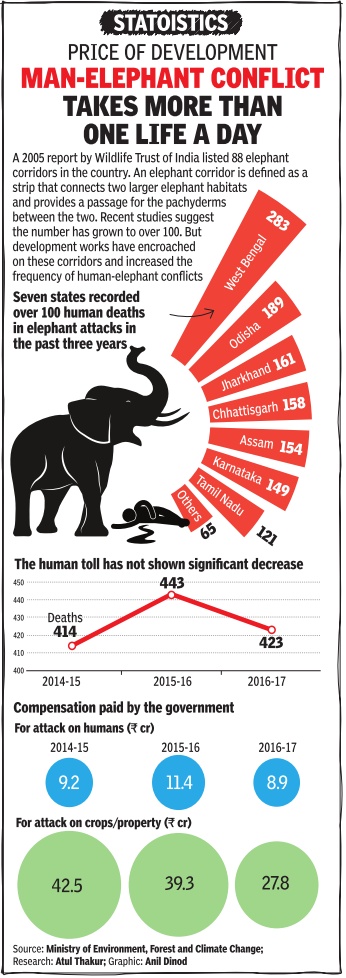

See graphic, 2014-17, Decreasing trend of humans killed by elephants; Compensation paid by the government for attack on humans and on crops or property, 2014-17, year-wise

2014-19: 2,398 humans killed

June 29, 2019: The Times of India

Over 2,000 people in India were killed by elephants while tigers claimed over 200 lives in last five years, the Union environment ministry informed Lok Sabha on Friday.

Nearly 494 persons were killed by jumbos last year alone. Responding to a query in Lok Sabha, junior minister for environment, Babul Supriyo said 2,398 people have died since 2014 up to March 31, 2019 due to human-elephant conflict with West Bengal recording the maximum 403 deaths in last five years.

West Bengal was followed by Nagaland where 397 persons were killed by the jumbos while 349 people died in Jharkhand.

The data was shared in a written response by Supriyo to a query raised by a Congress MP in Lok Sabha. According to the data, tiger-human conflict has killed 224 persons in India in the last five years with West Bengal once again recording the maximum number of human deaths in this case at 71. PTI

2017: In Assam, 40 jumbos die in 100 days

Data collected by conservationists has revealed that 40 elephants have died in Assam in the last 100 days. All of them have been killed due to unnatural causes, with the primary reasons being mowing down by moving train, electrocution, poisoning and accidentally falling in ditches especially in tea garden areas.

Herds of elephants have been regularly invading human settlements in search of food, damaging houses and crops in the process. As a result, incidents of man-animal conflict are steadily on the rise. “Elephants are considered to be a problem as they damage crops and properties during the harvest season. Also, unlike rhinos or tigers, elephants are not a state or national animal. Therefore, they evoke less public sentiment even when they die,” a conservationist, who did want to be named, pointed out.

He added that while public reaction is almost spontaneous in case of rhino deaths which are followed by strong condemnations and demands for exemplary punishment, the death of elephants fails to produce the same level of public outcry. “Unfortunately, we don’t see such outpouring of public support for elephants,” he said.

Bibhab Talukdar, secretary general of Aaranyak, an NGO that works on biodiversity conservation, said, “It is very unfortunate that more than 40 elephants have died in the last 100 days. It clearly shows that elephants are not getting priority when it comes to conservation of animals.”

While rhinos in the state are confined to national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, an estimated population of 500 elephants in Assam have habitats across all reserved forests. The state has five elephant reserves covering an estimated area of 10,967-sq km. Only a small portion of these reserves are in protected areas, in the form of national parks or wildlife sanctuaries, while the rest are reserved forest areas.

Conservationists pointed out that elephant reserves in the state do not enjoy the same level of protection as national parks. They fear the large-scale deforestation of elephant habitats, which lie outside protected areas, has endangered the survival of elephants.

2019: Assam’s Ladens

Naresh Mitra, Nov 7, 2019: The Times of India

From: Naresh Mitra, Nov 7, 2019: The Times of India

Osama bin Laden may have been killed by US Navy SEALs eight years ago, but his name keeps cropping up in parts of Assam. Except the Laden in question here is not the slain chief of terrorist group al-Qaida but a lone wandering elephant that killed five people in a single night in Goalpara district last week. A team of eight officers is on its tracks — aided by a drone that has already sighted the elephant in Satabari reserve forest — aiming to tranquillise and translocate the pachyderm before it strikes again.

The residents, meanwhile, are forced to live in fear as Assam struggles with a jumbo problem. At least 57 people have been killed in elephant attacks this year alone, the forest department said. Data submitted in Lok Sabha in July this year by the ministry of environment, forests and climate change also showed that the number of deaths in elephant attacks in Assam far exceeds those from other states with a high elephant population.

While Assam has the second-highest number of elephants at 5,719, according to the 2017 elephant population estimation carried out in 23 states, Karnataka has the highest at 6,049. In Assam, 86 people were killed in elephant attacks in 2018-19, 83 died in 2017-18 and 136 in 2016-17. In Karnataka, 13 people perished in elephant attacks in 2018-19, 23 in 2017-18 and 38 in 2016-17.

In Goalpara’s Matia, where five people were killed on October 29 by an elephant, now named Laden, residents find it difficult to sleep peacefully. “We wake up at the slightest sound. We have to be on constant vigil with our torches and firecrackers,” said Prafulla Kalita, a school teacher.

Such is the terror that elephants have wreaked in Assamese villages that the moniker ‘Laden’ has attached itself to jumbos that stealthily sneak into farms, raid crops and attack farmers. Honorary wildlife warden, Kaushik Baruah, said that the name came into use when an elephant killed a dozen people in several villages across Sonitpur district in 2006, a time when Osama Bin Laden was frequently in the news. The elephant was shot down later that year and his human namesake in 2011.

But an important realisation had dawned on people of Sonitpur and elsewhere — the conflict got more attention than it otherwise would have because the al-Qaida chief ’s name was attached to it. This had made it easier for them to get authorities to act and also to claim compensation in case of damage.

In the following years, every conflictridden district had its own Laden. But eliminate one tormentor and another would storm into the scene. Goalpara, host to another Laden, was earlier terrorised by a Laden who is believed to have killed many of the 40 people who died in elephant attacks in the district between 2016 and 2018, until it was found electrocuted. Wildlife experts, however, said elephants don’t attack unless their habitats are threatened or they are in a state of musth (when an elephant displays aggressive behaviour due to surge in testosterone levels).

The elephant that killed five in Goalpara is believed to be in a state of musth, which usually lasts for up to three weeks, said chief conservator of forests (lower Assam) Akashdeep Baruah. K K Sarma, head of surgery and radiology at College of Veterinary Science and part of the committee tasked with tracing the elephant, added, “We are ready with dart guns to tranquillise the elephant but we have to wait for a suitable opportunity.”

Shrinking resources and habitat loss has pitted the otherwise gentle herbivore against humans. According to Global Forest Watch, a repository of forest data worldwide, Assam lost 2388.46 sqkm of tree cover between 2001 and 2018.

Casualties are high on both sides. Parimal Suklabaidya, Assam’s forest and environment minister, said earlier this year that man-animal conflict killed 249 elephants and 761 people between 2010 and 2018.

Experts said that maintaining existing forest reserves and preventing further encroachment into forest territory are the only viable solutions to mitigating conflict.

Status, as in May 2020

June 10, 2020: The Times of India

GENTLE CREATURES VILE CRIMES

The Asian elephant ( Elephas maximus) found across India is listed as endangered by the IUCN and placed on its Red List

India has about 27,000 wild elephants. Reports have emerged of explosive-laden fruits, electric fences and crude bombs being used to keep away such elephants from eating farm produce

Even as the Palakkad tragedy shocked many, news emerged of another elephant having died in Kollam, Kerala, in April, after eating a firecracker-stuffed fruit There are over 3000 elephants in captivity in India. From tourism to agricultural labour, logging and participation in weddings and religious rituals, elephants are used in multiple forms of work

Young calf elephants are separated from their mothers and beaten and starved into submission. Many elephants work over 20 hours a day, exposed to heat, sound pollution, crowds, firecrackers, unhygienic conditions and dangerous transportation Several captive elephants have been found to be malnourished and dehydrated, beaten with metal prods and forced to work even when they are unwell Captive elephants are often kept standing for hours, chained or shackled, with even spikes embedded in their ankles

In 2018, Raju, a captive elephant forced to beg by his handler, was rescued by Wildlife SOS which found Raju starved, beaten, chained and wounded by metal spikes in his feet. Having suffered such cruelty for 50 years, Raju reportedly wept upon his rescue

Research: PETA Asia, The Independent, Huffington Post, BBC, IUCN

Methods used to keep elephants away/ 2020

From: Himanshi Dhawan, — Additional reporting by Sudha Nambudhiri in Kochi, June 7, 2020: The Times of India

From: Himanshi Dhawan, — Additional reporting by Sudha Nambudhiri in Kochi, June 7, 2020: The Times of India

From bees and chilli to tiger tapes, the tricks they try to keep elephants away

Shocked by the Kerala pachyderm’s death? Wildlife activists are finding kinder and more innovative ways to resolve the human-elephant conflict

The death of a pregnant elephant in Kerala this week after biting into a “snare bomb” — a pineapple filled with crackers – sparked national outrage but it also brought home the ugly realities of the human-elephant conflict. To save their crops from destruction, farmers often use brutal methods like fireworks, poison and electrocuted fences.

But are there better— and less violent — ways to keep the pachyderms at bay? Across the country, conservationists and wildlife researchers have been quietly working on a host of sustainable techniques. Inspired by successful experiments in Kenya, Prachi Mehta, executive director of Wildlife Research and Conservation Society and her team, decided to use bees as a deterrent since elephants don’t like the buzzing sound. Farmers in Karnataka’s Uttara Kannada district were encouraged to set up beehive posts, which also added to the income of the farmers who were able to harvest 15-30 kgs of honey, earning up to Rs 10,000 each. Karnataka has the highest population of elephants numbering over 6000.

Elephants have immense learning abilities, so conservationists have to constantly change tack. Besides watchtowers and elephant-proof trenches, indigenous methods like trip alarms, chilli tobacco ropes (the smoke burns the animal’s eyes without causing any permanent harm), fences made from used CDs (the shiny surface works as a torch and acts as a psychological barrier), taped sounds of tigers and distressed elephants, are being used in various parts of the country. Farmers also burn elephant dung or sprinkle tiger urine to keep pachyderms off their crops.

Technology is also coming in handy. Mobile-based warning systems, thermal detectors, and other sustainable solutions are being used in Indian forests. Tanzania, meanwhile, has tried condoms filled with chilli powder that keeps elephants from the crop, while drones have been used in some parts of Africa for surveillance.

In West Bengal, forests are using thermal sensors and GPS collars to provide early warnings that elephants are on their way. As a deterrent, many farmers have also shifted to “less appetising” crops like lemongrass and tea. Fragmentation of the forest area makes warning systems like fences less effective because there are multiple entry and exit points, says wildlife scientist Aritra Kshettry.

In Assam, the Wildlife Trust of India recently installed hanging fences along the Manas National Park boundary to keep elephants out of human habitat. Conventional fences to keep wildlife away from farmlands and human habitation are easily crossed by elephant herds by throwing trees.

These fences hang like a curtain with a gap underneath for smaller animals to cross and cannot be toppled easily by force. Though expensive (it could cost Rs 1-5 lakh a km), it has shown results in Sri Lanka. The fences are solar powered and give a mild shock to the pachyderms who learn to avoid them.

Valparai plateau in southern India was considered a hotspot of conflict for many years. In 2010, for instance, there were 100-150 incidents of crop or property damage and three or four human lives lost. But since 2011, there has been a steady decline, while property loss incidents have come down by a third, human loss is down to nil. The reason behind this drop is the early warning system set up by the National Conservation Foundation in collaboration with local communities. Interactions with elephants tended to occur when people encountered the animal unexpectedly, says NCF research scholar Sreedhar Vijayakrishnan. “Getting off a bus, or walking down a road at night, they would not see the animal. In some places, just putting up street lights solved the problem,” he says.

They also set up a bulk-SMS system to crowdsource information. When elephants are found in an area, a personalised location alert is sent to people in the vicinity. In Hassan district, Karnataka, villagers are now operating LED boards that light up to alert people that the elephant is within a kilometre.

But it’s always a hit and miss exercise with jumbos. Whether auditory units or fireball chains, fences or fruits, they have a way of quickly learning to overcome the obstacle.

As WRCS’s Mehta says, “If you put up a fence, they throw trees to break it, if you leave a part unfenced, they find it. If you put beehives, they learn to ignore them and even have the patience to wait till guards fall asleep before they hit the crops. We are always on our toes.”

Behaviour

2024 study

Krishnendu Mukherjee, March 1, 2024: The Times of India

Kolkata:The deceptively ponderous and gigantically affectionate Asian elephant has been documented — for the first time — burying calves who die prematurely. This behaviour earlier found mention in African literature, presumably referring to the larger elephant species from that continent.

The findings of multiple case studies have excited experts who study social behaviour in animals, as ‘calf burial’ has only ever been documented in a species of termite, but not in mammals.

In five case studies in north Bengal, herd members dragged the calves away from human settlements before burying them in “leg-upright position” in irrigation trenches inside tea gardens.

Details

‘Jumbos avoid paths where carcasses of calves are buried’

The study was published in the internationally acclaimed Journal of Threatened Taxa. “The study area covered fragmented forests, tea estates, agricultural lands and military establishments between 2022 and 2023,” said Parveen Kaswan, DFO of Jaldapara wildlife division, formerly DFD of Buxa Tiger Reserve, who co-authored the study with Akashdeep Roy, a senior research fellow at IISER Pune. “We explained burial strategy of elephants in irrigation drains of tea estates by presenting five case reports,” he added.

“We found that the elephants carry the carcasses, holding on to the trunks or legs, for a distance before burying them,” Kaswan told TOI. “Direct human intervention was not recorded in any of the five deaths. Through long-term observation, we also found that the elephants in this region avoided paths where carcasses were buried.” The cases have been documented in Debpara, Chunabhati, Bharnabari, Majherdabri and the New Dooars tea gardens near Gorumara and Buxa. The calves were aged between three and 12 months.

Most surprising, according to the study, is the positioning of the carcasses that are buried: in all five cases, the legs were upright, with the head, trunk and dorsal regions fully buried. “The positioning could be explained for better grip for herd members to hold and lay the calf in the trench. This behaviour also reflects the care and affection of the entire herd for the dead calf. It suggests that because of a space crunch, the herd members prioritise the head for burial before feet,” added Kaswan. While burying each carcass, members of the elephant herd “vocalised” for about 30-40 minutes. This may signify mourning, the researchers conjecture, though more study needs to be done to explain this, they said.

According to long-term observation, elephant movement frequency had reduced by up to 70% in these areas. “Jumbos started using parallel pathways, clearly avoiding the previous path where carcasses were buried,” the study claims, adding that this behaviour contrasted with that of African elephants, who spend alot of time investigating and exploring the remains.

Man- elephant conflict: solutions

In Kerala, strobe lights keep jumbos off farms

Rajeev KR, December 10, 2018: The Times of India

The swirling multicolour LED lights that give dance floors their zing have found a totally different use in Kerala’s Wayanad. The forest department has deployed 360-degree rotating party lights in forest fringes to scare off wild elephants from human habitations, and it seems to have worked.

Officials said the lights had been successful in keeping stray jumbos at bay in the human-wildlife conflict hotspots of Chethalayam under the South Wayanad forest division. Measures like elephant proof trenches (EPTs), granite walls and solar fences had failed to check the menace in the area.

“We have installed 14 multicolour LED light units in Chethalayam range at spots where elephants had breached the EPTs and solar fences. It has proven to be an efficient deterrent so far; the areas have not reported any stray elephant incidents for the past one and a half months, despite it being the paddy harvest season,” P Renjith Kumar, South Wayanad divisional forest officer, said.

Ajas K, a local farmer, said the lights had been found effective against wild boars too. Chethalath forest range officer V Ratheesan said the lights were mostly installed in corridors created by jumbos to reach human habitations. “We installed the party lights after noticing that elephants had an aversion to strong lights.” He said the LED lights were cost-effective as well, with a unit of bulb and battery costing around Rs 4,000.

“Normal flash lights have been used against straying elephants in places like Jharkhand. However, we must see if elephants get accustomed to them over time,” Wildlife expert PS Easa said .

Inter-state transfers/ relocations

The language barrier

Priyangi Agarwal, May 26, 2018: The Times of India

Elephants are intelligent, they can remember and have the ability to understand human body language. Authorities at Dudhwa Tiger Reserve (DTR) are banking on just that to break the Kannada–Hindi language barrier and help the 10 jumbos which have come from Karnataka to become a part of the reserve’s patrol force.

When DTR authorities worked out plans to transport 10 elephants from Karnataka, they were aware that these jumbos would respond only to commands given in Kannada. But jumbos’ new handlers would speak in Hindi. To surmount the language problem, six mahouts of Dudhwa were sent to Karnataka for a two-month training before shifting the jumbos across 2,500km to DTR by road.

Giving details, Mahaveer Kaujlagi, deputy director of DTR, told TOI, “During the two-month training in Karnataka, our mahouts learnt Kannada words which were used by elephants’ handlers there. Besides, 12 mahouts from Karnataka arrived along with the elephants here to help the pachyderms adjust in a new home.

“Our mahouts give instructions in both Hindi and Kannada to make elephants understand that their meaning is same. Elephants have started picking up Hindi words. Our mahouts are currently giving commands only in Hindi and have taken full control of the jumbos.’’

Irshad Ali, who has been working as a mahout in DTR for the past 24 years, said, “During the training, we learnt the Kannada words used for giving commands like ‘turn, lie down, sit’ and ‘go backwards’. We started giving commands in both languages to elephants to make them learn new Hindi words. It took only 12 days for elephants to understand Hindi words used for several instructions.’’ Ali said.

“The body language of mahouts plays an important role in giving commands to elephants and it is same in both UP and Karnataka. For instance, if we want elephant to take right turn, we loosely release our right leg but move our left leg. However, if the elephant does not listen to its mahout, we have to tap its forehead with a stick to make them listen to our commands.’’

Kartick Satyanarayan, co-founder and CEO, Wildlife SOS, said, “Elephants are intelligent mammals and learn quickly. They understand the expectations and behaviour of their mahouts.’’

Of the 12 mahouts who came from Karnataka, five would be leaving for home this week while the others would be going in 10 days. “The mahouts of Karnataka stay at a distance from elephants so that the jumbos are detached from them,’’ said Kaujlagi.

Forest officials said once the four-month quarantine period is over and the elephants get used to their new home, a health check-up would be conducted and then they would be made to meet and interact with the 13 resident elephants of Dudhwa.