Medical malpractice: India

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

[[Category:India |M ]] | [[Category:India |M ]] | ||

[[Category:Law |M ]] | [[Category:Law |M ]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Crime |M ]] | |

| + | [[Category:Health |M ]] | ||

=Introduction= | =Introduction= | ||

Revision as of 17:54, 7 May 2015

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Introduction

Raj Chengappa

November 15, 2013

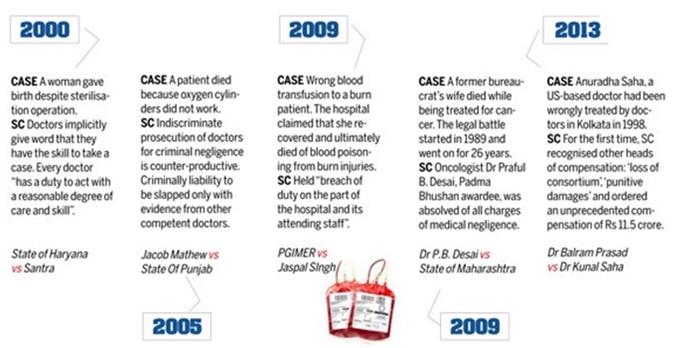

For years, the medical profession in India had neglected the warning symptoms. Shielded by flaccid regulatory authorities and a near comatose judicial system, the four lakh-strong community of doctors was almost immune to charges of malpractice.

Even when the problem grew to serious proportions, they failed to resort to corrective surgery. Now, aggrieved patients are beginning to wield the scalpel. Especially after a ruling made by the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission that medical services were liable under the powerful Consumer Protection Act of 1986.

Here's an alarming statistic: 98,000 deaths from medical injuries occur in India every year, reports an ongoing NABH study. Here's another: medico-legal cases have gone up by 400 per cent in the Supreme Court in the last 10 years, according to legal resource, Manupatra. Patients are afraid of an uncaring medical system. Doctors are terrified of assertive patients. Hospital life is under scrutiny, and with it the authority and autonomy of doctors. "Doctors are afraid," says Dr Arvind Kumar, chief of robotic and chest surgery at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital in Delhi. "The trust factor between doctors and patients is slowly coming down and there is no solution in sight."

"Negligent doctors need to be punished. But medical errors are also often 'system errors' and not the result of an individual physician's negligence," says Dr K. Srinath Reddy, former head of cardiology with AIIMS and currently president of Public Health Foundation of India. The scientific basis of good clinical practice depends on combining a well-gathered history of illness, physical signs and results of tests into an estimation of probabilities of possible diagnoses, he explains. While medicine is not an exact science, which always gives a 'yes' or 'no' answer, the 'art' of medicine lies in converting scientific evidence to standard management guidelines created by expert bodies, for all practitioners to follow. "Apart from minimising errors and avoiding unnecessary tests and treatments, adherence to guidelines forms the best defence against allegations of medical negligence," he adds.

The buzz among doctors is also on crippling compensations. In the latest issue of the British Medical Journal, Indian doctors have come head to head. "In India, healthcare is supposed to be regulated by a quasi-judicial medical council that has failed to protect against widespread negligent and irrational treatment," writes Dr Kunal Saha, a US-based doctor who received 'historic' justice-an unprecedented compensation of Rs.11.5 crore-in October 2013, for medical negligence that caused his 36-yearold wife Anuradha's death in 1998. "Large payouts awarded by the courts of law may be the only way to instill accountability for wayward doctors and to save lives."

A bench of Justices Dalveer Bhandari and H.S. Bedi had pointed out the need to protect doctors from "malicious prosecution": "It is our bounden duty and obligation of the civil society to ensure that medical professionals are not unnecessarily harassed or humiliated so that they can perform their professional duties without fear and apprehension."

Change will require looking at medical practice and malpractice in a new light: not just at material costs, but that the trust that exists between patients and doctors remains sacred.