Babar, emperor

(→Babar in Hindustan) |

(→BabriGardens) |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

According to the Babarnama, the year 934AH (1527/28AD) passed in conquering Chandairi. The people of Chandairi fought valiantly and Babar, for the first time, saw the traditions of ‘jauhar’ –– intention to fight until the last breath. They also sacrificed their own wives and children before the fight. While Babar was still in the area of Chandairi, he dispatched a lashkar to the east with the hope that it may control the factions of Ibrahim’s revolting Ameers. News came that his Ameers had abandoned Qannauj and were retreating. As soon as he heard this news he moved east. | According to the Babarnama, the year 934AH (1527/28AD) passed in conquering Chandairi. The people of Chandairi fought valiantly and Babar, for the first time, saw the traditions of ‘jauhar’ –– intention to fight until the last breath. They also sacrificed their own wives and children before the fight. While Babar was still in the area of Chandairi, he dispatched a lashkar to the east with the hope that it may control the factions of Ibrahim’s revolting Ameers. News came that his Ameers had abandoned Qannauj and were retreating. As soon as he heard this news he moved east. | ||

| − | + | ||

==Mosque at Ayodhia== | ==Mosque at Ayodhia== | ||

According to Babarnama, heading east, Babar passed through Lucknow and travelled from there towards Awadh. He stayed at the junction of Ghaghra and Sarda rivers, 10 kilometres above Awadh — Awadh (Ayodhia) being the place where the Babri mosque, which has caused so much bloodshed in India since 1855, was situated. According to Babar in Babarnama, he never went to Awadh. He said he stayed a “few” days at the junction of the two rivers mentioned above, to control the Afghan factions. Then someone brought him the news that there was a nice place up the river where plenty of shikaar was available. He thus moved northwest. | According to Babarnama, heading east, Babar passed through Lucknow and travelled from there towards Awadh. He stayed at the junction of Ghaghra and Sarda rivers, 10 kilometres above Awadh — Awadh (Ayodhia) being the place where the Babri mosque, which has caused so much bloodshed in India since 1855, was situated. According to Babar in Babarnama, he never went to Awadh. He said he stayed a “few” days at the junction of the two rivers mentioned above, to control the Afghan factions. Then someone brought him the news that there was a nice place up the river where plenty of shikaar was available. He thus moved northwest. | ||

Revision as of 14:35, 1 September 2013

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Babar in Hindustan

By M.H.A. Beg

Text and photographs from the archives of Dawn

“FROM the year 910AH [1504-1505AD], when Kabul was taken, to 932AH [1525-1526 AD], I have wished for Hindustan. Partly because of my ameers’ lack of interest and partly because of my brothers’ lack of cooperation, the Hindustan campaign seemed impossible and the realm remained unconquered. But all such impediments have now been removed. None of my little begs [lower-grade ameers] and officers are able to speak out in opposition to my purpose any longer … We led the lashkar to Hindustan five times within the past seven or eight years.”

Thus according to the Babarnama, Babar’s struggle for Hindustan was planned and achieved, gradually, over a period of 21 years. Babar wanted to go to Hindustan because his great-great-great-grandfather, Amir Taimur, had been there and Babar carried his book Zafarnama, the book of victory, with him on this campaign.

As it was under his influence and control, Babar headed towards India through the KhyberPass. On reaching Nilab (a crossing on the river Sindh), he ordered the counting of his troops. Bakhshis counted it to be 12,000.

The route

Babar writes in Babarnama that after crossing the river he had to make a decision. The usual route spread from Lahore to Delhi through the plains, which did not get much rain that year. There was a possibility of water and grain shortage, however, the mountainous areas had received plenty of rain. He thus chose the route through Parhala (near Rawalpindi), Kalar Kahar (today’s Kalda Kahar), Sialkot and Kalanaur (near Gurdaspur). He may also have been influenced by the news of Daulat Khan pulling together a lashkar of 20 to 30,000 at Kalanaur. Daulat Khan was the governor of Lahore. He was removed from this post by Babar when he took over Lahore in 930AH (1523-1524AD).

Babar swiftly crossed the river Jehlum below the town, the river Chenab at Behloolpur, and the river Beas with the purpose of attacking Daulat Khan in a fort at Malot. Daulat Khan could not stand the onslaught and submitted while his son Ghazi Khan escaped to the mountains.

Babar found Ghazi Khan’s library at Malot very interesting. He had already heard of it and hoped it would have a valuable collection, which indeed it did have. He sent a few volumes of interest to his sons, Humayun and Kamran.

Ahead of him now laid the plains of India, all the way up to Bengal, but there were more obstacles in the way. The first of these was Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi, the Afghan Sultan who was based in Agra. On the South of Ambala, at a place called Sarsawa, Babar pondered and chose Panipat to be the place for the encounter.

Panipat

Panipat was a vast plain, where the river Jamna became broad. The town itself had many large houses and palaces, which could be kept for protection. According to Babarnama, Babar ordered trenches to be dug on the other side and large trees to be dumped in order to protect the left flank. He divided his lashkar into centre, right and left wings, along with an advanced guard and reserves at the back. In front of the lashkar, he kept arabas (carriages with guns) tied together with leather ropes. A space was left in between two carriages so that six men with match-locks could stand behind shields. Between all the sections, there was enough space left for shooting arrows and for quickly dispersing the troops in any direction.

Ibrahim Lodhi’s force appeared to be running around haphazardly. They were taken aback by Babar’s orderly and well-formed troops, which could very well be compared to a solid wall. This confused them and they didn’t know which way to attack. Still, being in overwhelming majority, they attacked fiercely and pressed mainly against the right wing of Babar’s troops. Noticing this, support was sent to the right wing from the reserves through the gaps between the troops. They surrounded Ibrahim’s lashkar from two sides. The arrows being shot from these gaps were deadly. Babar felt that they could prove to be the major weapon against the enemy in this encounter, that would bring him victory. Ibrahim was also killed in the battle, an occurrence which usually does not happen as sultans usually escape. Ibrahim Lodhi’s stand was extraordinary.

Kala Aam

Panipat is now a large city with great plains all around it which were bustling with commercial activity. A memorial has been established of three battles (Bairam and Himu, 1525-1556, Abdali and Marathas, 1761 and Babar and Lodhi) fought there. The city was locally known as Kala Aam — in memory of the last battle which took place near a mango tree. It is said that the tree had turned black with the blood of the soldiers killed in the battle.

The memorial, surrounded by a low stone wall, is situated about five kilometres away from the town. Here two plaques have been put up commemorating the first and second battles, along with a pillar that harks back to the third battle. There is also a small museum within the compound.

Ibrahim Lodhi lies buried in the city. There is a red-brick platform constructed on two different levels, on which rests his grave. The grave is plastered but there is no roof over it. A small plaque with words carved in Urdu indicates that it is the sultan’s final resting place. However, the area around it seems neglected. Occasionally a person or two shows up to recite the Fateha. Other than this there is no obvious Muslim presence in the city, for the main population comprises Punjabi Sikhs.

Kabuli Bagh Mosque

Though generally unknown and not mentioned very often by Babar himself, his lashkaris established a mosque while at Panipat. The lashkar and its bazaar must have stayed in a bagh where the mosque was built. To the Hindustanis, the foreigners staying there at the time of the battle came from Kabul, thus the garden was named Kabuli Bagh. This garden doesn’t exist anymore but the remnants of the mosque are still there. Its left dalan has crumbled down. According to Dr Ram Nath, who has devoted his life to doing research on Indian Mughal architecture and has written a four-volume book Mughal Architecture, the mosque was not made of stone and was not Babri in style. The building as well as the arches and dome were more Pakhtoon. These days its main dome is being repaired with the application of chemicals to save the crumbling masonry.

According to Babarnama, Babar marched 80 kilometres to Delhi and camped by the river Jamna. He stayed there for two days, visited the dargahs (Nizamuddin, Qutab) and the two famous ponds (Hauz Shamsi and Hauz Khas) along with the tomb of the kings (Balban, Khiljis and Lodhis), but does not describe them in his book. He also had a khutba (sermon) recited in his name after the Friday prayers. He had already dispatched Humayun to Agra, from Panipat, and he himself followed hurriedly. He was overwhelmed by the size of the country he had set out to conquer.

Poetic skirmish

Bayana was a strong fort situated on the southwest of Agra. Its ameer, Nizam Khan would not surrender to Babar. After exchanging messages, he did, however, make certain demands which Babar thought to be excessive. Immediately, Babar composed a rubai and sent it to him as a note of warning:

O’ Meer Bayana, do not wage war with a Turk, you know of our skills and courage, if you fail to listen and do not come before long, There is no need for me to explain the consequences that will follow!

The threat and persuasions worked in the end.

Disaffection in the lashkar

Like his predecessors, Babar also suffered from disaffection in his troops. Many of them were not comfortable with the hot tropical climate of India and did not want to stay put. The heat was blazing, as it was summer. Alexander of Macedon and Amir Taimur both decided to leave this land and take the troops back, but Babar proved superior to both in this encounter. He spoke to the troops and persuaded them through his poetry. He retorted to an ameer, Khawaja Kalan, who decided to go back after listening to a rubai:

O God, thank you for giving me Hind and Sind and other kingdoms, if you (Khawaja Kalan) do not have enough strength to bear the heat and want to face the cold, you have Ghazni.

Babar’s hoax

Immediately after Panipat, Babar distributed the wealth he had acquired among his sons, ameers, wives, tribes and troops. Every single person in Kabul and Warsak got a Shahrukhi. Gifts were also sent to Samarqand, Khurasan, Madina and Mecca. Babar gave away so much that people called him qaladar.

He also played a hoax on one of his old servants, Asas. Asas was sent an asharfi and upon receiving it, he was upset for three days about the meagreness of the present. As a result, when gifts were distributed in Kabul, according to special instructions, Asas was blindfolded and an asharfi was hung in his neck, which weighed 15 seers. Babar has not mentioned this story in any of his collections; however, Gulbadan Begum quotes it in Humayun Nama.

The Rana

There were still contenders of power lurking around, two of whom were immediate threats. Rana Sangha was in the southwest of Agra and Afghan ameers of Ibrahim Lodhi in the east. They had revolted while Ibrahim was in power. The ameers were far away but Rana had marched up close.

Rana Sangha had been proactive. He crossed the dry plains from Chitor towards Agra in 933AH (1526-27AD) and stayed at Bayana. Babar moved from Agra to Sikri and chose a lakeside at Khanwa, in the west of Sikri. His men were surprised at the speed with which Rana moved. There was also a fear among the troops as the astrologer Mohammad Sharif’s predictions were not favourable. This was also the first time that Babar faced a Hindu opponent.

Babar assumed the role of a Muslim fighter and jihadi against an “infidel”. He renounced drinking, abolished taxes on Muslims and in an act of philanthropy, ordered the construction of a well. Near that well, he shed wine laden on three rows of camels brought by Baba Dost from Kabul. All the glasses, cups and containers were also shattered.

Khanwa encounter

On the eve of the battle, Babar spoke to his men encouraging them to be fearless, persuading them to fight till their last breath as life and death were in the hands of the Almighty. The plan and organisation of his lashkar appeared to be on the same pattern as was in Panipat. Babar, unfortunately, left the description of the organisation and the battle to Shaikh Zain. Zain was a Persian scholar who used all the power of his vocabulary, rhetorical words and bombastic sentences to motivate the troops. It appears that the rush of Rana was on the right wing of Babar. Babar used the reserve force to support that wing and also utilised it to surround Rana from all sides. Then he pushed towards the centre, which caused chaos amongst Rana’s men. They could not stand the onslaught and retreated. Rana escaped wounded.

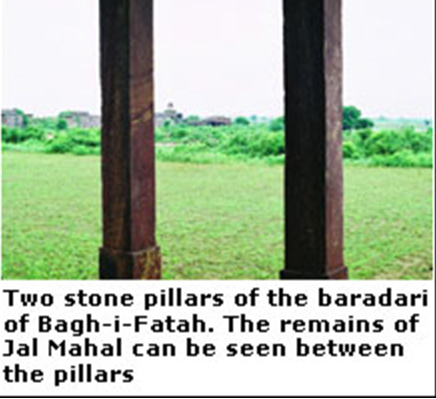

Bagh-i-Fatah

On his return from Khanwa, Babar ordered the plantation of another garden at Sikri. Some remnants of this garden are still visible. The well was constructed into a three story baoli with rahat to bring water to the surface. It can still be seen behind the Sikri ridge. The present route to it is through the Nagar village after passing Moti jheel. The site of the garden is uncertain but it is probably near the present Ajmeri Gate at Sikri. A part of the Baradari which is described in Dr Ram Nath’s book, Babar’s Jal Mahal: Studies in Islam as the Chaukundi, the four-sided shelter from the sun, has survived. Now there is a small lake there as well, which must have been a large one, for in the centre of the lake Babar had the Jal Mahal constructed. A portion of it is still present. It has an outer covered corridor and an inner octagonal building where one could sit and relax. The entire building is made up of local red stone. There must have been water in between the two buildings as they could only be reached by boat. It must have been a beautiful site to rest and enjoy.

Even today it is not that bad a picnic spot. Gulbadan Begum in Humayun Nama says that her father use to sit there and write his book (Babarnama). Dr Ram Nath has described this site in his article ‘Studies in Islam’ (1981).

Having gotten through the battle of Khanwa, Babar went through a period of respite. He lived in Agra for most of the time but never sat idle except when he was ill, of which there were many episodes during his Hindustan years. He was very aware of the lack of running water from brooks and springs, which he had become used to in Farghana and Kabul. He had always loved gardens and spent most of his life in them. He wanted to build a few here as well.

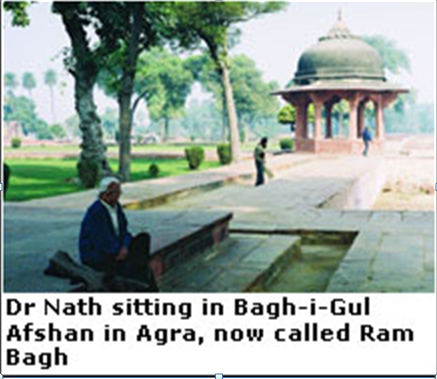

BabriGardens

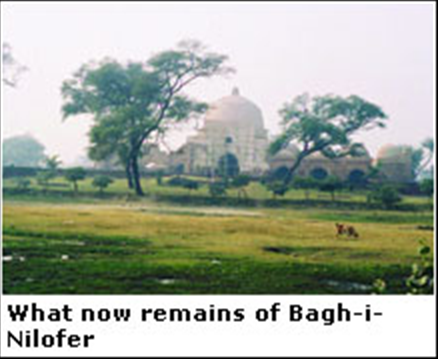

It is written in Babarnama that Babar planted and had also ordered the planning and construction of a number of gardens in and around Agra. The known gardens are Hasht Bahist, Zar (Nur) Afshan, Nilofar and Gulafshan. The last one survives partly as Ram Bagh. It was renamed by Jahangir as Aram Bagh but recent upsurges in Hindutva dropped the letter ‘a’ from the name. Ram Bagh is situated opposite the Agra water works, at the north of the AgraBypassBridge. It was a well-planned charbagh with square grass-plots with walkways in between. Running water was provided after collecting it in a large tank by rahats from the river Jamna. The water was made to fall in three levels of terraces. Its original planning is still visible, however, time and neglect have left their marks on it.

A part of Bagh Hast Bahisht survives today as Mehtab Bagh. It was planned and renamed by Shahjehan. It lies on the other bank of the river Jamna, right behind the Taj Mahal. Another remnant of history is Babar’s Nilofer garden at Dholpur. Dholpur lies 68 kilometers from Agra on the road to Gwalior, where one has to leave the main road to go towards Gor village. The octagonal hauz is still there, cut in a solid rock just as it was described by Babar.

According to the Babarnama, the year 934AH (1527/28AD) passed in conquering Chandairi. The people of Chandairi fought valiantly and Babar, for the first time, saw the traditions of ‘jauhar’ –– intention to fight until the last breath. They also sacrificed their own wives and children before the fight. While Babar was still in the area of Chandairi, he dispatched a lashkar to the east with the hope that it may control the factions of Ibrahim’s revolting Ameers. News came that his Ameers had abandoned Qannauj and were retreating. As soon as he heard this news he moved east.

Mosque at Ayodhia

According to Babarnama, heading east, Babar passed through Lucknow and travelled from there towards Awadh. He stayed at the junction of Ghaghra and Sarda rivers, 10 kilometres above Awadh — Awadh (Ayodhia) being the place where the Babri mosque, which has caused so much bloodshed in India since 1855, was situated. According to Babar in Babarnama, he never went to Awadh. He said he stayed a “few” days at the junction of the two rivers mentioned above, to control the Afghan factions. Then someone brought him the news that there was a nice place up the river where plenty of shikaar was available. He thus moved northwest.

The architecture of the Babri mosque is also not Babri. It is more akin to the Pakhtoon period. It was constructed by one of Babar’s ameers, Baqi Tashqandi, and was named after Babar, as a number of other mosques spread all over north India like Sambal, Panipat, Rohtak, Palam, Maham, Sonepat and Pilkhana were named. All were constructed during his reign but none appear to have been built on his orders.

Gwalior

Early in 935AH (1528-29AD), Babar found some time for leisure. He travelled enjoying the sights and sounds of his newly acquired country. One of Babar’s ameers captured Gwalior. Babar was interested in looking at the famous fort and visited it. His description of Gwalior is outstanding.

Gwalior is now a tourist town, approachable by road, train and air. The Fort of Gwalior lies at the centre of the city, situated high up on the mountain. It can be seen from all around as a huge fort going on for miles. It would be wise to visit it in a vehicle otherwise one will find oneself walking the entire day. The fort is walled around. Inside, the area is hilly with most of the buildings destroyed. Babar describes the northeast section of the fort, where there are palaces of Man Singh and his son Vikrama. He liked the palace of Man Singh which had four stories, all constructed of stone but with certain dingy and dark places.

Vikrama’s palace was not so well-received by him and is now crumbling down. Babar also describes in Babarnama the Urwa valley which is in the middle of the fort facing west. There he saw huge Jain statues which he did not like and ordered to be removed. These, since, have been restored. The valley is enclosed on three sides with various sized statues.

There are a number of other mandirs as well inside the fort. The most famous being ‘Sas bahu ka mandir’ (mother-in-law and daughter-in-law’s place of worship). In fact these are two mandirs, the mother-in-law’s is large and the daughter-in-law’s is smaller. The traditional rivals could not even pray at one mandir.

In the town, there is an important Sufi shrine related to Babar. Babar mentions in Babarnama, Ghaus Gwaliori, a Sufi of ‘Shattari tariqa’, who helped in the capture of the fort and also came to him to save Rahim Dad, the governor who was in revolt at the time. The shrine was built during Akbar’s days. It is a fine building with beautiful cut stone work all around. Within this compound also lies the final resting place of Tansen, Akbar’s musician.

Babar also visited a waterfall in an area south of Gwalior which he calls Jharna. We searched for it but never found it. However, while searching for the waterfall, we found another important personality. Allama Abul Fazl, the panegyric Mughal historian who lies buried about 30 kilometres south of Gwalior on the road to Jhansi.

Bihar and Bengal

Most days of 935AH were passed shadowing Babar’s ameers who were trying to subdue the Afghan factions’ spread over Bihar and Bengal. Babar by this time had become a Shahenshah. He could now afford to send out commanders deputising, like his sons and his ameers, to look after and subdue the revolts. Still he followed them to be near them and keep overall control. The Afghan factions were not giving them a stand to fight but adopted a game of hide and seek instead. Babar reached up to Maner (near present Patna) where he paid homage to a local Sufi, Shaikh Esa Muneri. Soon Bihar was taken over. At the time Bengal was under Nusrat Shah who showed interest in an agreement which was concluded after a few exchanges of embassies, accepting overall suzerainty of Babar.

He then began his journey back to Agra.

Most of Babar’s autobiography, the Babarnama, was also compiled during his Hindustan period. He even wrote it when he was returning to Agra from Bihar. At the river Ghaghar, he encountered torrential rain and storm which pulled down his tent and his papers were blown off and got drenched. He spent the entire night there saving the papers and drying them.

During this period he also wrote letters to his sons and ameers, which shows his interest in their teaching, language, spelling, grammar and responsible attitudes for ruling, behaviour and interpersonal relations.

In this period he also mentions how he ordered the distance between Agra and Kabul to be measured, post stations to be established at certain distances and the way they should be maintained financially.

September 09, 2007

=

Babar: The avid adventurer

Reviewed by Dr Muhammad Reza Kazimi

Babar, although he composed memorable poetry in Persian, was concerned with preserving both his faith and his language.

THE prince of a small principality called Farghana, Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babar succeeded his father at the tender age of 12 but was soon besieged by his uncles. But when he died, it was as the founder of the glorious Mughal Empire. The details of his life by any other pen would also have held great interest, yet posterity has reason to be very grateful that Babar wrote an autobiography. One of the very few monarchs who could wield the pen and the sword with equal facility, Babar wrote his Waqa-i-Babar in his native Turki in spite of being fluent in Persian.

As a soldier, scholar, poet and emperor, Babar has excited the fascination of readers and scholars across the world. His autobiography is praised for its candour, and rightly so, but it is not his candour alone which holds the reader spellbound. Babar’s great grandson also wrote his memoirs which are equally candid; Jehangir shared his ancestor’s eye for detail and love for nature.

Babar had the observation of a connoisseur, but for all these merits his life as an emperor is not attractive as his career as a warrior. Waqa-i-Babar, Toozk-i-Babari, or Babarnama as the autobiography is variously known, has been translated and annotated by Khan-i-Khanan in Persian and by Annette Beveridge and Wheeler Thackson in English. The Humayunnama by Gulbadan Begum and Tarikh Rashidi by Mirza Haider Dughlat are supporting works by contemporary relatives. The contents of Waqa-i-Babar have been told and retold thus it is not necessary to review the text. What need to be reviewed are the notes supplied by the editor, Hasan Beg.

Besides, presenting an authentic text is an adventure on its own especially because the native Turki of Babar has undergone much travail. In Turkey (Asia Minor) it began to be written in the Latin script, and in Turkistan (Central Asia) it came to be written in the Cyrillic script. This made the task of reconstructing the original text quite difficult. In fact, it has created a controversy over how the name Babar is to be spelt or pronounced.

The Waqa-i-Babar has proven to be a popular text and has been copied by many scribes. With the proliferation of texts, errors also multiplied and a critical text of the Waqa-i-Babar became the first pre-requisite for scholars. The British Library houses 10 manuscripts and from these Hasan Beg fixed on the manuscript calligraphed by Musvi Ali Khan. Hasan Beg mentions a critical edition prepared by I.G. Manu of the Kyoto University of Japan, which was prepared with the help of three Turki and one Farsi manuscripts. The text based mainly on the manuscript of Musvi Ali Khan, was translated into Urdu by Professor Younus Jafri of the DelhiCollege in 2004. The annotation is by Hasan Beg.

We must understand Hasan Beg’s quest for an authentic manuscript in the light of the fact that no holograph of the Waqa-i-Babar exists. Hasan Beg surmises that the holograph may have been lost in the tornado of 935 AH, which Babar himself describes. This is not likely; for when Babar was describing the tornado, he would have described the loss of his manuscript as well. Later, he surmises that it may have been lost during the arduous journey undertaken by Humayun. This is the only possibility, for it provides for the opportunity to have copies of the Waqa-i-Babar made by Babar’s son and a Persian translation ordered by Babar’s grandson.

The change of script, that is Latin for Turkish and Cyrillic for Turki, has indeed resulted in confusion as is evident from the variants of Babar’s name. William Erksine translated the Waqa-i-Babar or Babarnama in 1826, and he spelt the emperor’s name as Babar. So did Annette Beveridge in her earlier writings including the facsimile of the Turki manuscript, but when she published her translation in 1912-1921 she spelt the name as Babur. The Russian historians, namely Kohr and Smirnov, were attuned to the Cyrillic script so they preferred Babar. In French, Pavet de Courteille spelt the name as Babir. My teacher Professor Najeeb Ashraf Nadvi in an article published in the Ma’arif (Azamgarh 1822) preferred Babur, but also admitted that rhymes in Persian poetry may change.

Hasan Beg himself prefers Babar, mostly on the ground of facility of pronunciation.

In this background we can understand his lament over the corruption of the Turkish script. He says that even Urdu’s debt to Turki has not been acknowledged. He lists common words of Urdu like Apa, Baji, Begum, Khan and Khanam which are all taken from Turki. Babar, although he composed memorable poetry in Persian, was concerned with preserving both his faith and his language. For his son Kamran he composed the imperatives of the Hanafi fiqh in Turki verse. The Manawi Mubeen composed by Babar has been translated into Urdu and should be available in print by the end of the year under the auspices of the Pakistan Historical Society.

Among the appendices included by Hasan Beg is a remarkable one on the ailments suffered by Babar. From the symptoms described by Babar, Hasan Beg has been able to hypothecate a diagnosis. He states that Babar suffered from tuberculosis and the dreaded disease had travelled to his abdomen during the terminal stage. Medical histories are as useful to understanding behaviour as are temperaments reflected in literary output.

Another appendix relates to influence of mystics on the Mughals. Hasan Beg shows how Khwaja Ahrar Naqshbandi was able to avert a war between Babar’s father and his uncles, but as far as the spiritual influence of his progeny is concerned, it comes through as uninspiring. The last entry of the Waqa-i-Babar relates to August 25, 1530 AD, according to which he forgave the rebel Rahim Dad at the instance of Shaikh Muhammad Ghous of Gwalior. The last phase, regarding Babar sacrificing his life for his son Humayun, is carried in a purported addendum. However, Stanley Lane Poole refuses to ascribe it to Babar on the ground that it is not found in the editions of Teufil or Pavet de Courteille, as well as based on stylistic considerations,. This scene is nonetheless graphically recorded by Abdul Fazl and carries full conviction.

In conclusion, one would like to cite the tribute paid by Babar’s English translator Annette Beveridge: ‘His autobiography is to be counted among those invaluable writings which have been praised in every age. It shall be apt if they are put in the same class as the confessions of St Augustine and Rousseau, the memoirs of Gibbon and Newton. Its like is not to be found in Asia.’ Ms Beveridge leaves out only one detail: none of the other authors mentioned by her include an empire builder like Babar.

________________________________________

Waqa-i-Babar By Zaheeruddin Muhammad Babar Indus Publications, Karachi ISBN 978-0-9554383-0-1 396pp. Rs1500