The President of India

(→Elections) |

m (Pdewan moved page President of India to The President of India without leaving a redirect) |

Revision as of 20:27, 5 August 2017

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

THE PRESIDENTS OF INDIA

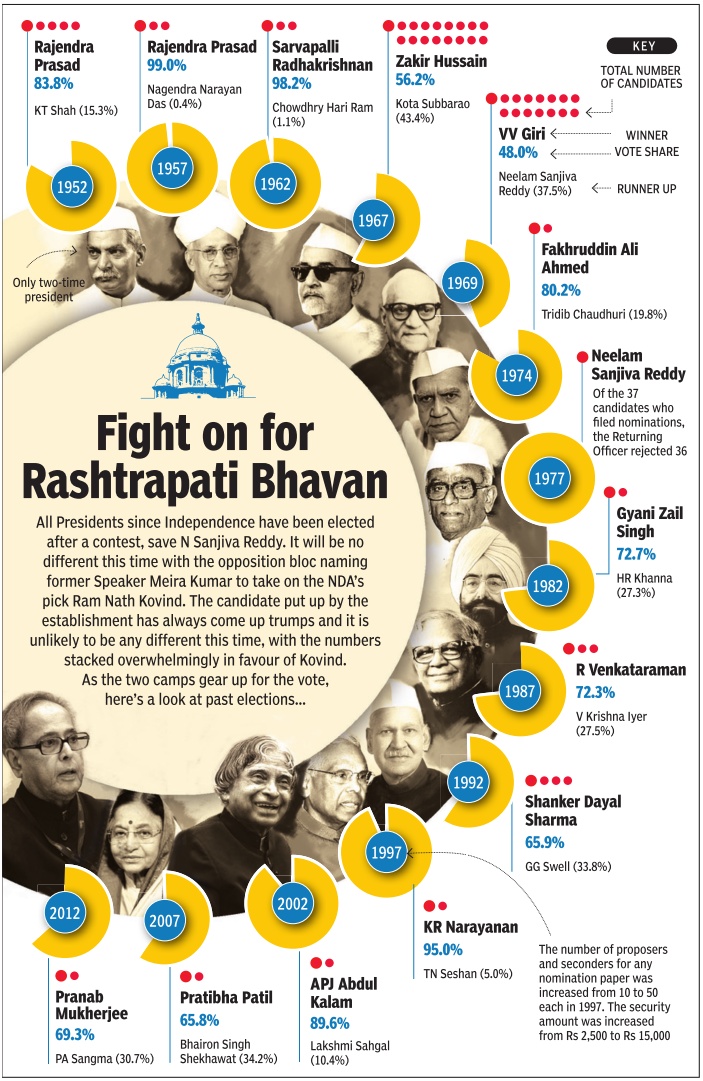

Dr Rajendra Prasad (1884-1963) ............................................ 26 January 1950-13 May 1962

Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888-1975) ........................... 13 May 1962-13 May 1967

Dr Zakir Hussain (1897-1969) ................................................ 13 May 1967-3 May 1969

Varahagiri Venkata Giri (1894-1980) ..................................... 3 May 1969-20 July 1969 (Acting)

Justice Mohammad Hidayatullah (1905-1992) ................... 20 July 1969-24 August 1969 (Acting)

Varahagiri Venkata Giri (1894-1980) ..................................... 24 August 1969-24 August 1974

Dr. Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (1905-1977) .............................. 24 August 1974-11 February 1977

B.D. Jatti (1912-2002) ............................................................... 11 February 1977-25 July 1977 (Acting)

Neelam Sanjiva Reddy (1913-1996) ...................................... 25 July 1977-25 July 1982

Giani Zail Singh (1916-1994) .................................................. 25 July 1982-25 July 1987

R. Venkataraman (1910-2009) ................................................ 25 July 1987-25 July 1992

Dr Shankar Dayal Sharma (1918 -1999) ............................... 25 July 1992-25 July 1997

K.R. Narayanan (1920-2005) .................................................. 25 July 1997-25 July 2002

Dr. Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam (1931-2013) ............................................ 25 July 2002-25 July 2007

Smt. Pratibha Patil (b-1934) ................................................... 25 July 2007-2012

Sh. Pranab Mukherjee 2012 -17

Sh. Ram Nath Kovind 2017-

Elections

The 1969 election

Dhananjay Mahapatra , Jun 26 2017 : The Times of India

In 2017 Congress fielded Meira Kumar as its candidate for the President in an attempt to arrest further widening of cracks in opposition unity .

Thus, Kumar is achieved what her more illustrious father Jagjivan Ram could not despite coming within sniffing distance nearly half a century ago in 1969, when Congress was staring at a split -one faction led by Indira Gandhi and the other `Syndicate' led by S Nijalingappa.

The Supreme Court recorded evidence of nearly a hundred witnesses, which included future president Fak hruddin Ali Ahmed and future PM I K Gujral, while dealing with a serious challenge to V V Giri's election as president. With the blessings of Indira Gandhi, Giri had defeated the official Congress candidate N Sanjeeva Reddy .

Dalit card was not a popular recourse then for reaping a political harvest as it is today . In Shiv Kirpal Singh vs V V Giri [1970 AIR 2097], the SC records in detail how an acrimonious fight erupted between the two factions of Congress over the presidential candidate. It also records how Jagjivan Ram came close to becoming a presidential candidate.

“No consensus being attained at the meeting of Congress Parliamentary Board held on July 12, 1969, the matter was decided by voting. The PM and Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed voted for Jagjivan Ram, while Morarji Desai, Y B Chavan, S K Patil and K Kamraj voted in favour of N Sanjeeva Reddy ,“ the SC had recorded.

Since the majority decided in favour of Reddy , an overruled and `greatly upset' Indira Gandhi played her trump card by dumping Jagjivan Ram in favour of then VicePresident V V Giri. It would not have been possible in today's India, where `pro-Dalit' tag to any decision adds a knockout punch in politics.

The SC had upheld Giri's election as president but came to a sad conclusion after evaluating testimonies of politicians, who decades later held the reins of power. The SC had said, “A number of witnesses have not told the whole truth.As a matter of fact, we were distressed to see truth being sacrificed at the altar of political advantage by these witnesses.“

If by not insisting on Jagjivan Ram as its candidate the Congress missed a chance to elect a Dalit as President in 1969, it made amends nearly three decades later by install ing K R Narayanan as the first Dalit President in 1997.

A year later, Narayanan stalled appointment of judges to the Supreme Court, insisting that Justice K G Balakrishnan be appointed as a judge.He sent back recommendations for appointment of four judges to to the then CJI A S Anand with a noting, “I would like to record my views that while recommending appointment of Supreme Court judges, it would be consonant with constitutional principles and the nation's social objectives if persons belonging to weaker sections of society , like SCs and STs, who comprise 25% of the population, and women are given due consideration.“

CJI Anand was no pushover. He said all eligible candidates, including those from SC and ST communities, were considered while making recommendation for appointment as SC judges. “Our Constitution envisages that merit alone is the criterion for all appointments to the SC and HCs.And we are scrupulously adhering to these provisions. A vacancy may not cause as much harm as a wrongly filled vacancy ,“ he had retorted.

With Narayanan maintaining a rigid stand, Justice Anand had to rush to Rashtrapati Bhavan and convince him that if Justice Balakrishnan was appointed as an SC judge in 1998, he would have a tenure of five and half years as CJI and supersede many others.

Narayanan relented but ultimately succeeded in pushing for Justice Balakrishnan's appointment as an SC judge, which came on June 8, 2000. He became the first Dalit CJI on January 14, 2007 and enjoyed the third longest tenure as CJI, after Y V Chandrachud and S R Das. So what will India prefer -the course adopted by Indira Gandhi or the one by Narayanan? If governments and politicians sincerely strive to provide basic rights, amenities and education to Dalits, they will not need either of the courses to prove their mettle.

All but two elections challenged in SC

The President is the benign head of government constitutionally mandated to sign on the decisions of the council of ministers headed by the Prime Minister. Exaltation is stitched to the post by making him the symbolic supreme commander of the armed forces.

What makes presidential elections interesting and no holds barred is the fact that the anti-defection law does not apply . No party can issue a whip to compel its MPs and MLAs to vote for a particular candidate.

On paper, it makes MPs and MLAs cast conscience votes to elect the first citizen of the country . In reality, it permits political parties to encourage cross voting. That is why so much political muck flows beneath the sanctified exercise to elect the head of state.

From Rajendra Prasad, the first President, to Pranab Mukherjee, every presidential poll has been challenged in the Supreme Court, except two those electing S Radhakrishnan and Pratibha Patil. A presidential election can be challenged only in the SC, which sets up a bench of five judges to hear such petitions.

In the first presidential election, Rajendra Prasad defeated Prof K T Shah by garnering 83% of the total vote value. An alumnus of London School of Economics and a prolific contributor to the Constituent Assembly debates, Prof Shah was too dignified to challenge Prasad's election in the SC.

In 1957, Prasad secured a second term by getting 99% of the vote value. But one `inten ding candidate', Dr N B Khare, challenged Prasad's election and alleged that it was improperly conducted. The SC threw it out [Dr N B Khare vs EC 1958 AIR 139] without even going into the merits of the allegations.

By the time Dr Zakir Hussain was elected the third President of India, the political landscape had undergone a dramatic change. One Babu Rao Patel challenged Hussain's election in the SC [1968 AIR 904].

Patel alleged that the conscience vote mandated to be cast by MPs and MLAs under the Presidential and Vice-Presidential Elections Act, 1952, was violated because of `undue influence' exerted by the PM and cabinet ministers who openly canvassed and pressurised elected representatives to vote for Hussain.

The SC threw out the petition and said, “Any voluntary action which interferes with or attempts to interfere with the free exercise of electoral right would amount to undue influence. It cannot take in mere canvassing in favour of a candidate at an election. If that were so, it would be impossible to run democratic elections. It is difficult to lay down in general terms where mere canvassing ends and interference or attempt at interference to with the free exercise of any electoral right begins.“

Wish the SC had decided what would constitute `undue influence', for the word came back to haunt the presidential elections in petitions filed in the SC later.

The very next presidential election, warranted by Hussain's sudden death in 1969, witnessed murky political manoeuvring by then PM Indira Gandhi and her aides. Against Gandhi's wishes, Congress chose N Sanjiva Reddy as the official candidate. She responded by putting up then Vice-President V V Giri as the challenger and made it known that he had her blessings.

One Shiv Kirpal Singh challenged Giri's election and the SC in its judgment [1970 AIR 2097] recorded his allegations thus, “Supporters of the returned candidate -Indira Gandhi, Jagjivan Ram, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, Yunus Saleem, Karan Singh, Dinesh Singh, Swaran Singh, I K Gujral, Satya Narain Sinha, K K Shah and Triguna Sen -were all occupying high ministerial positions in the central government and they misused these positions for furthering the prospects of the returned candidate.“

This remains the only time when evidence was led by parties in the SC in a presidential election petition and Giri was asked to answer it.The SC brushed aside the evidence of `undue influence' and termed it mere canvassing. It ruled that the evidence was insufficient to hold it as misuse of official machinery.

Apart from this, a pamphlet carrying scurrilous and vulgar allegations against Sanjiva Reddy was openly distributed in the Central Hall of Parliament alleging that if Reddy got elected as President, then Rashtrapati Bhavan would be converted into a “harem“ and that he would destroy democracy through his dictatorial methods.

This too was discarded by the SC. It said though the pamphlet could possibly have influenced the minds of voters, the petitioner could not establish either the `connivance' or `consent' of Giri in the printing and circulation of the pamphlet.

Presidential polls changed course with Giri's election. The elections of the next three Presidents Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, N Sanjiva Reddy and Giani Zail Singh -were unsuccessfully challenged by advocate Charan Lal Sahu, who was never a se rious candidate.

Sahu had also challenged the elections of K R Narayanan and A P J Abdul Kalam, only to invite the SC's ire and warning. One Mithilesh Kumar Sinha had challenged the elections of Shankar Dayal Sharma and R Venkataraman.

A serious challenge to the election of Zail Singh, who had infamously said he would have unhesitatingly picked up the broom if Indira Gandhi had told him so, came from 27 MPs from Lok Dal, Democratic Socialist Party of India, BJP and Janata Party , which had fielded Justice H R Khanna as their candidate.They had questioned Singh's suitability as President.

Interestingly , ex-CJI M H Beg, who had sided with the SC's majority judgment in 1976 upholding suspension of fundamental rights during Emergency and had become chairman of Minorities Commission in 1982, critically questioned Justice Khanna's suitability as President by pointing out the infirmities in Justice Khanna's dissenting judgment in the ADM Jabalpur case. The MPs alleged massive misuse of official machinery by the government in getting Singh elected as the seventh President.

The SC dismissed the MPs' petition [1984 (1) SCC 390] and said, “Suitability of a candidate is for the electorate to judge and not for the court to decide. Suitability is a fluid concept of uncertain import.The ballot box is, or has to be assumed to be, its sole judge.“

Since then, the suitability of a person for the President's post has indeed remained a fluid concept.

Pranab Mukherjee's election was challenged by defeated candidate P A Sangma, who alleged that at the time of filing of nomination, Mukherjee held an office of profit being chairman of the council of Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata. Parliament had found it to be an office of profit and included it among exempted ones to prevent disqualification of MPs.

The SC had no escape route but to recognise that this indeed was an office of profit post. However, it deftly stepped around Mukherjee's pos sible disqualification by ruling with a slender three to two majority that in reality there was no profit from the post to the candidate.

In its December 11, 2012 ruling, it said, “Categorising it as an office of profit did not really make it one, since it did not provide any profit and was purely honorary in nature.“

It remains to be seen what political manoeuvring and characteristics the 2017 presidential election throws up.

Legal powers

Presidents and governors, power of

The Times of India Sep 5, 2011

Dhananjay Mahapatra TNN

Mercy plea or Lokayukta: Can Prez and guv act in personal capacity?

Recent al heads decisions – rejection by constitution of mercy - petitions in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case by the President and the Gujarat governor’s decision to appoint Lokayukta – have caused debates both on constitutional and political lines.

The Constitution vests sovereign power in the President and governors. Governance in the Centre and states are carried out in their name. But they do not have unbridled power to decide mercy petitions in exercise of exclusive powers conferred on them under Articles 72 and 161. They have to act in aid and advice of the council of ministers, both at the Union and state levels, as have been held conclusively by the SC. The SC had grudgingly agreed with Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes, who had said, “Pardon is not a private act of grace from an individual happening to possess power. It is part of a constitutional scheme. When granted, it is the determination of the ultimate authority that the public welfare will be better served by inflicting less than what the judgment fixed.” So, the President by rejecting the mercy pleas has, on the aid and advice of the Union council of ministers, come to the conclusion that public welfare would not be served by reducing the punishments awarded to the convicts. The Constitution does not provide for any mechanism to question the legality of decisions of President or governors exercising mercy jurisdiction. But the SC in Epuru Sudhakar case has given a small window for judicial review of the pardon powers of President and governors for the purpose of ruling out any arbitrariness. Now, it is in the process of examining whether there should be a time limit for deciding mercy petitions, which keep pending for years inflicting mental torture on condemned prisoners awaiting their day. The question of the President and governors, conferred with wide powers under the Constitution, acting in their own capacity without consulting the elected government came in for wide discussion in Shamsher Singh case [1975 SCR (1) 814].

A 7-judge constitution bench was amused by the ingenious arguments by a counsel supporting vesting of discretionary powers with President and governors to step around the SC’s consistent view that India has accepted the Cabinet form of government.

The counsel argued – wherever the Constitution has expressly vested powers in the President or the governors, they belong to them alone and cannot be handled on their behalf by ministers under the relevant rules of business. It is similar to the arguments justifying Gujarat governor Kamla Beniwal’s decision to appoint Lokayukta without consulting the chief minister.

The SC had answered this question by saying, “How ambitious and subversive such an interpretation can be to parliamentary (and popular) authority unfolds itself when we survey the wide range of vital powers so enunciated in the Constitution. Indeed, a whole host of such Articles exist in the Constitution, most of them very vital for the daily running of the administration and embracing executive, emergency and legislative powers either of a routine or momentous nature.”Discussing the governors, the court said they had “power to grant pardon or to remit sentence, the power to make appointments including of the chief minister, the advocate general, district judges, members of the public service commission”.

It listed such kind of power vested in the President – supreme commander of the armed forces, appointment of judges of the SC and HCs, power to dismiss a state government under Article 356 and an entire army of public servants who continue in service at the pleasure of the President. If President and governors acted on their own, then parliamentary democracy “will become a dope and national elections a numerical exercise in expensive futility”, the court had warned.

The 7-judge bench said if this was true of Indian Constitution and the system of governance, then “we will be compelled to hold that there are two parallel authorities exercising powers of governance of country, as in the dyarchy days, except Whitehall is substituted by Rashtrapati Bhawan and Raj Bhawan. The Cabinet will shrink in political and administrative authority”.

It said such a distortion “would virtually amount to a subversion of the structure, substance and vitality of our Republic, particularly when we remember that governors are but appointed functionaries and the President himself elected on a limited indirect basis”.

Irrespective of who gets appointed and who gets pardon, let politicians not introduce politics into the constitutional scheme, the thread that keeps the country united. In case of Gujarat, there is a difference— the statute clearly provided that Lokayukta will be appointed by the governor in consultation with the chief justice of the HC. The Modi government can amend the statute, which on Shamsher Singh judgment logic, appears untenable. But as long as it is there, why does the BJP want the Modi government to have primacy in Lokayukta appointment but grandstands for an independent process for Lokpal?

President's decisions subject to judicial review: HC

The Times of India, Apr 21 2016

President too can go wrong, says Uttarakhand high court

Vineet Upadhyay

The legitimacy of the President's decision to suspend the Uttarakhand assembly is subject to judicial review as even he can go wrong, the Uttarakhand high court observed.

The court was responding to an argument by additional solicitor general Tushar Mehta, appearing on behalf of the Centre, who contended that the President relies on his political wisdom in many matters. “You cannot have absolutism. President can go wrong,“ the division bench comprising chief justice K M Joseph and Justice V K Bisht commented. The judges went on to remark that the court's order, too, is “always open to judicial review“.

Even as the bench declared at the conclusion of arguments on Wednesday that the hearing would continue the next day , Abhishek Manu Singhvi, counsel for former chief minister Harish Rawat, put forward his apprehensions that the Centre may revoke President's rule and call BJP to form the government in the state. Reacting to this, the court issued a subtle warning, “We still have tomorrow.We hope they will not provoke us.“ By the end of the day , opin ion among legal circles was that the court was likely to reserve its orders on the matter. Meanwhile, hectic parleys that continued throughout the day focused on the events in the assembly on March 18. The HC, citing the governor's report and correspondence, about what had happened in the state ssembly on that day , pointed out that there was “no mention of nine (rebel) MLAs of Congress making the demand of the division of vote on the floor. Instead, as per the material we have, the leader of opposition had made the demand of the division of vote“, the bench noted, adding that “what we have understood is that everything was proceed ing towards a floor test on March 28“. It also said there was “absolute absence of material that would create an apprehension in the mind of the governor“ that central rule needs to be imposed.

Talking about the Union Cabinet note about recommendation of central rule, the bench asked additional solicitor general Tushar Mehta, “Why so much secrecy around this cabinet note?“ Mehta denied any secrecy , adding that the note was only submitted to the court as “confidential material“.

During the arguments, Singhvi raised a question on whether a solitary instance of a speaker denying a division would be sufficient to impose central rule. He also alleged that none of the governor's reports to the President recommended imposing of Article 356 or said there was “failure of constitutional machinery in the state“. Singhvi told the court that BJP filed the complaint against Arya on April 5 after which the speaker had already sought a reply from Arya on April 12. “Centre's argument that he did not take any action is baseless,“ he added.The court said it is “taking a serious note of this“. The Centre will submit its clarification.

Method of election

In Prez poll, MPs not bound by party whip, Mar 20 2017: The Times of India

Who elects the president?

The president is not elected in a direct election by the people, but by an electoral college consisting of the elected members of both houses of Parliament and MLAs of the state legislative assemblies, Delhi and Puducherry . Nominated members do not vote in these elections.

Is the value of every MLA's vote the same?

No. The principle is that the total value of the votes of the Union legislature and state legislatures should be more or less the same. Also, each state must have a value within the total value of votes for all states corresponding to its share in the total population.Hence, a population-based formula is devised to calculate the value of votes. The 84th Constitution Amendment Act, 2001 states that until the relevant figures for the first census after 2026 are published, the population of states for calculating the value of votes in presidential election shall be the figures from the 1971 census. Hence, the value of votes of a particular state is calculated by dividing its 1971 population by the number of elected seats in the state assembly multiplied by thousand (population(no of MLAx1000). For instance the value of a Delhi MLA's vote is 58 which is calculated on the basis of the NCT's 40.7 lakh population in 1971and 70 seats in the legislative assembly . In a similar way , the value of the vote of an UP MLA is 208, the highest in the country , while it is 7 for Sikkim, the lowest.

How is the value of MP votes calculated?

The total value of these state votes is added and then divided by the number of elected members in both Lok Sabha (543) and Rajya Sabha (233) and rounded off to the nearest whole number.

This puts the value of each MP's vote at 708. There are all told 4,896 electors consisting of 776 MPs and 4,120 MLAs. The total value of votes of MPs is 5,49,408, while for the 4,120 MLAs it is 5,49,474 (the numbers are slightly different because of rounding off the decimals). One can see that the Constitution seeks to ensure that the neither the Union nor the states will have an advantage here. This is done because apart from being the ceremonial head of state, the president is responsible for appointing the prime minister. In a situation when no party or coalition gets a clear majority , it is the president who exercises his or her discretion and this can be crucial.

How is the voting done?

Members of the electoral college can vote according to their conscience and are not bound by party whips. The voting is also by secret ballot. The ballot pa per does not have any party symbol. It has two columns, the first containing the name of the candidate and the second where the elector has to write hisher preference.

The number `1' means first preference and so on. In the first round of counting, a candidate has to get more than half of the total first preference votes polled. In a situation in which no candidate gets this, the returning officer excludes the candidate with the lowest first preference votes and distributes his votes among the remaining candidates on the basis of second preference.The process continues until someone reaches the quota.

Who is eligible to contest the presidential election?

Any citizen of India over the age of 35 who is qualified for election as a member of the Lok Sabha can contest presidential elections. Candidates cannot hold any office of profit under the Centre or states.

A candidate's nomination paper must be subscribed by at least 50 electors as proposers and another 50 as seconders. An elector can subscribe to the nomination of only one candidate as proposer or seconder. If heshe has signed the nominations of two candidates, the signature for the first set of papers will be valid while the second becomes inoperative.