Crop stubble burning: India

(→See also) |

(→Happy Seeder, straw spreader) |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

Kamboj sold around 200 Happy Seeders this season, up from 100 last year. Landforce, another big producer, reported sales of 400 this year, significantly higher than the 10-15 Happy Seeders the company sold in 2016. | Kamboj sold around 200 Happy Seeders this season, up from 100 last year. Landforce, another big producer, reported sales of 400 this year, significantly higher than the 10-15 Happy Seeders the company sold in 2016. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Ploughing stubble back into the soil== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F10%2F19&entity=Ar00316&sk=D8687731&mode=text Manish Sirhindi, October 19, 2018: The Times of India] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Farmers in ‘model’ Punjab village don’t burn crop stubble, plough it back into soil | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | When smoke from burning paddy stubble was choking Delhi last year, a village near Nabha in Punjab was doing its bit to keep the air clean. Not a straw was burnt in Kalar Majra, where 60 families farm about 700 acres. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “The government chose our village as a model, and gave all the machinery needed to manage the crop residue,” says Bir Dalvinder Singh, a Kalar Majra farmer who persuaded his neighbours to heed the government’s call against burning stubble. The eco-friendly step earned praise from the National Green Tribunal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although there is no assistance from the government this year, about 70% of Kalar Majra has decided not to burn paddy stubble, with good reason. Ploughing it back into the soil is good not only for Delhi’s air but also the farmers’ bottom line. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Few know this better than Surjeet Singh of Sandhugarh village in Punjab’s Fatehgarh Sahib district. He hasn’t burnt crop residue on his 45 acres for the past 15 years. “I use a ‘happy seeder’ to manage the stubble, and for the last two harvests I used the straw management system of a combine harvester,” he said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Surjeet had his moments of doubt when costs shot up in the first two years. “It appeared to be a bad decision,” he said, but he started saving on fertiliser and fuel from the third crop onwards. He claims his use of fertiliser has halved. “Despite that my crop yield has increased by at least 20%.” | ||

| + | Parvinder Singh, of Mavi Kalan village near Patran, is another advocate of the happy seeder. It not only saves diesel at the time of tilling, but also water, as the fields don’t need irrigation before sowing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Cost of giving up stubble burning too much for some | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet the yield goes up by 2-2.5 quintals of wheat per acre, as the paddy straw acts as a crop nutrient,” Parvinder Singh said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | So, why do most farmers in Punjab still burn their crop residue? Bir Dalvinder, who used to be a techie in Gurugram and has braved Delhi’s yearly smoke episodes, says cost is the main hurdle. Jeet Mohinder of Kularan village in Patiala district agrees, saying residue management costs Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,500 per acre in the first two years. “Most farmers consider it a risk, and take the easy way out by burning the stubble.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pressure from farmers’ unions is another deterrent, says Bir Dalvinder. “Some marginal farmers have been misled by the kisan unions. They say they will burn the residue if the government does not provide help. But we are trying to persuade them not to fall for the misinformation campaign.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The government has tried to encourage stubble management with subsidies on equipment, but Jeet Mohinder says it should give farmers financial benefits for the first three years instead. Once the decomposed stubble boosts soil fertility, “farmers will realise the benefits of not burning it. They will be eager to find ways to dispose of it in an environment-friendly way.” | ||

=Health issues= | =Health issues= | ||

Revision as of 08:44, 21 October 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Origin of burning crop stubble

Background

Amit Bhattacharya The Times of India, Nov 03 2015

Widespread crop burning began over dozen yrs ago

Satellite images reveal age-old norm

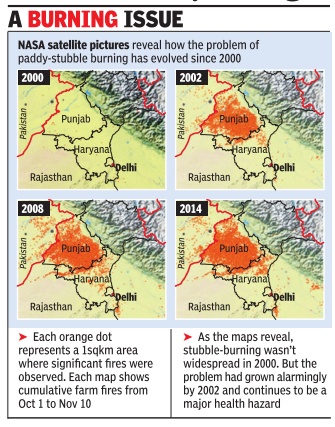

The practice of burning paddy stubbles in Punjab and Haryana has of late been recognised as a major contributor to air pollution in the national capital region during October-November. Satellite images, however, reveal that the problem had already reached alarming proportions as early as 13 years ago.

Farm fires in the region began to register in satellite images in year 2000. Not that stubble burning did not take place before that, but the practice probably became widespread enough in 2000 for it to show up in the 1-square-km resolution satellite images. By 2002, the `fires spots' in the satellite pictures had filled up almost the entire state of Punjab and parts of northern Haryana.

TOI obtained the data from Nasa's FIRMS Fire Mapper website, which enables users to access satellite imagery from the past.

To get a season-wide picture perspective, cumulative fire data was considered from October 1 to November 10 -a 40-day period when farmers in the region burn their paddy stubble to prepare the fields for the next crop.

What the information reveals is that successive governments in the states have failed to check the practice despite a law that bans stubbleburning. The problem assumes more serious proportions with each passing year due to the fact that pollution from other sources are on the rise in NCR. So, the added pollutants that come from biomass burning make the situation graver.

The concentration of farm fires in Punjab and northern Haryana shows the extremely high proportion of farmers opting to grow paddy during the kharif season. As Ruby Singh Sandhu, a big farmer from Mallekan village in northern Haryana puts it, “Farmers in the cotton growing areas of Punjab and Haryana have been slowly shifting to paddy for more than a decade now.“

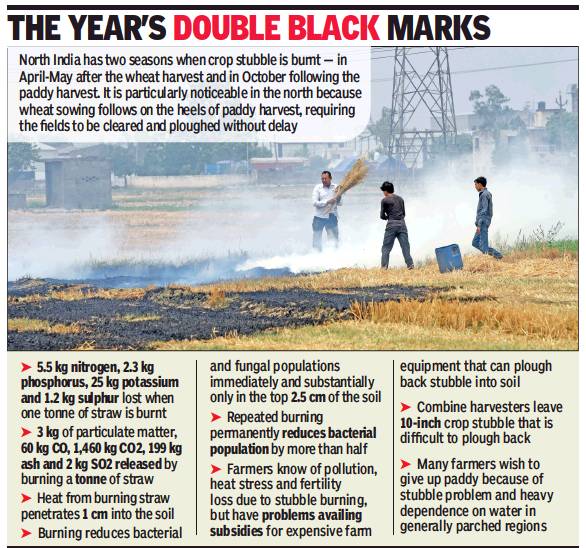

Disadvantages of burning crop stubble

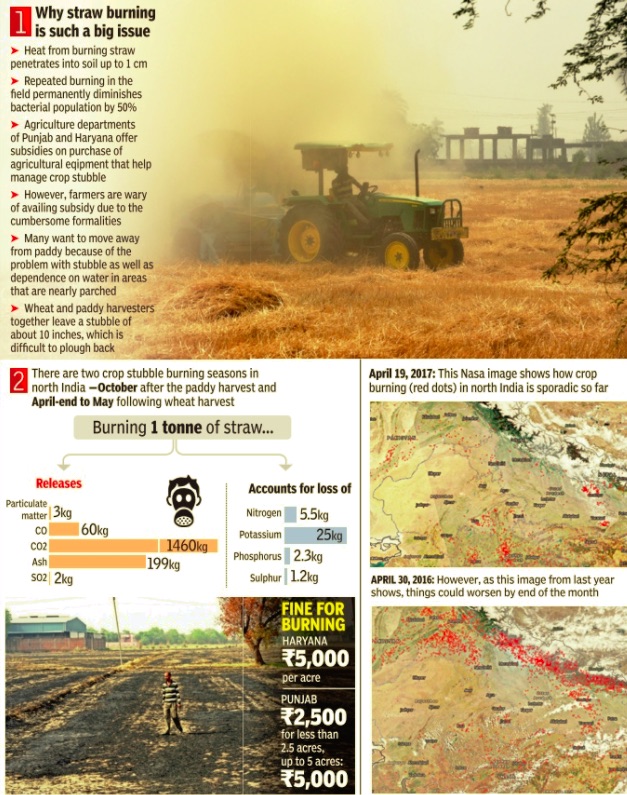

From: Jayashree Nandi, Happy seeders beyond farmers’ reach, f ield f ires still a sad reality, May 5, 2018: The Times of India

See graphic:

The multiple disadvantages of burning crop stubble

Did mechanical harvesting start the epidemic?

The advent of combine harvesters in Punjab, Haryana and UP, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, is being blamed for the practice of burning crop stubble. To save time and money, as well as to tackle labour shortage, more and more farmers are opting for mechanical harvesting of crops using combine harvesters.

Farmers say the blades of combine harvesters don't cut the crops close to the ground, and leaves the plant stalk, usually up to two feet high, standing.

Sarabjit Singh, a farmer from Virpur village of Bijnor district in UP , said the people who operate combine harvesters don't cut the crop close to the ground since they are more concerned about getting the grain. “The operators try to clear the maximum possible area in a day since they charge per acre. Hence, they leave the task of clearing the crop to the farmers. The crop stalk is very high at times,“ he added.

Farmers find it difficult to plough the crop residue back into the soil using harrows and, instead, resort to burning the stubble to clear the fields for the next crop. The problem is more pronounced in the winter, with little time available for farmers to prepare the fields for sowing wheat after harvesting paddy.

The prevailing rates for harvesting paddy using combine harvesters in north India are in the range of Rs 1,300-1,500 per acre. On the other hand, labour charges of harvesting paddy manually are around Rs 1,600 per acre, a practice more prevalent in UP, MP and parts of Haryana.

Another farmer, Baljinder Singh Sidhu from Kotbhara vil lage in Punjab's Bathinda district, said the days of manual harvesting were better: “Earlier, when paddy was manually harvested, the crop was cut close to the ground. While the grain was obtained after threshing, the leftover plant stalk or straw was stored as fodder for cattle.“

Sadhu Singh, director of Akhtiar Agro King, an agriculture machinery manufacturing unit in Moga, said the problem was acute in Punjab since the farmers don't consider paddy straw to be of any use.

“In case of wheat, the combine harvesters usually cut the crop close to the surface. However, farmers in Punjab don't keep paddy straw, so they don't insist on a close cut for the crop,“ he added.

Alternatives, solutions

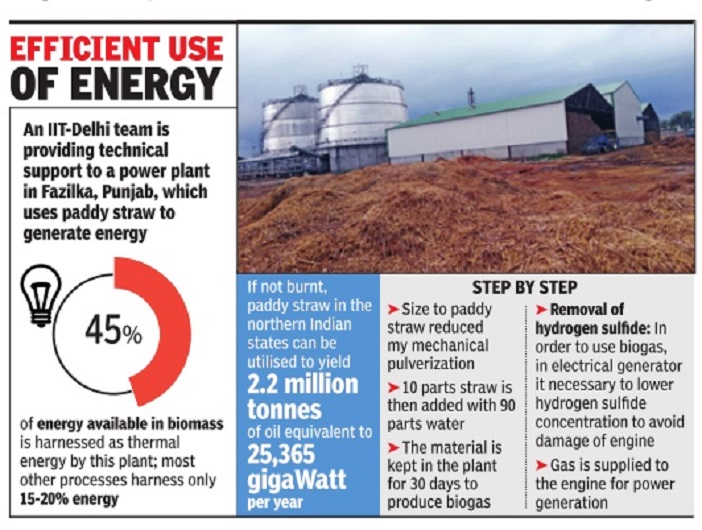

IIT/ D: Make biogas instead of burning stubble

Manash Gohain, IIT-D shows how Punjab can re-use farm waste, Nov 13 2016 : The Times of India

Instead Of Burning, Paddy Straw Can Be Used To Make Biogas

Are you a farmer? How about earning a handsome amount from the stubble left behind in your field instead of burning it and adding to the pollution level?

How about also getting biofertiliser and sustainable energy in the same deal?

An IIT-Delhi team has provided technical support to Asia's first biogas-based power plant which is now operating on paddy straw for largescale biogas production in Fazilka, Punjab. The system is based on 100% use of paddy straw and has been generating nearly 4,000 cubic metres per day of biogas from 10 tonnes of straw. This is in turn generating 1MW power.

This sounds like welcome way out of the pollution mess that the capital has found itself in. Going by reports, 70% of Delhi's air pollution is due to stubble burning in Punjab, Haryana and other parts of north India.

Professor V K Vijay of Centre for Rural Development and Technology (CRDT) of IIT-D said paddy straw, if not burnt, could yield 2.181 million tonnes of oil equivalent or 25,365 gigaWatt hours per year.“Straw burning can be avoided through installation of commercial biogas industries by using these agro biomass for both power generation and biofertiliser production to enrich soil health. The present level of utilisation at Fazilka has shown a saving of 120 gigaJou les per day energy which otherwise would have been released to the atmosphere by direct combustion along with the release of enormous pollutants,“ said Vijay.

He added, “Burning straw biomass amounts to 30kg of particulate matter, 600kg of carbon monoxide, 14.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide and 20kg of sulphur dioxide emissions, which have significant toxicological properties and are potential carcinogens.“

Abhinav Trivedi, a doctoral fellow working under the guidance of Vijay , developed this process that has better efficiency than conventional processes for biogas generation.

Dr Ramchandra of CRDT said the project was started in December 2011 by the Punjab government in association with Sampurn Agri Ventures Pvt Ltd. “After our intervention for around six months, the plant is running for nearly eight hours per day for the same amount of straw against two hours earlier. It is generating 7,500 kiloWatt hour per day and nearly five tonnes of bio-fertilisers per day ,“ he said. Ramchandra also said that the system was able to harness over 45% of energy available in the material.

Fuel-grade ethanol

Dec 25 2016, The Times of India’'

There might be some solution in sight as the biofuels in tion in sight as the biofuels industry now says fuel-grade ethanol could be a more valuable product from crop residue that, when burnt, not only causes air pollution but literally sends crores of rupees up in smoke. According to Pramod Chaudhari, executive chairman of Praj Industries, a leading biofuels technology provider, 250 litres of fuel grade bio-ethanol can be produced from a tonne of farm residue using second-generation processing technology .

A step towards increasing biofuel availability will be taken when Pradhan and food processing minister Harsim rat Kaur Badal lay the foundation stone on Sunday of the first bio-ethanol refinery at Bathinda in poll-bound Punjab. Alive to the issue, the government has asked state-run fuel retailers to set up bio-ethanol refineries. “Second-generation ethanol production technology using rice-paddy straw in Punjab and Haryana will be a permanent solution to crop burning,“ oil minister Dharmendra Pradhan said in a November 7 tweet.

Estimates, including those by Nasa, pegged the quantity of farm residue burnt at 32 million tonnes in Punjab alone. This could mean some six billion litres of bio-ethanol. This can also translate into a big saving for the country, which meets 80% of its crude requirement through imports, since adequate availability of bio-ethanol will boost the government's plan to achieve 20% blending of petrol and diesel by 202122. That level of blending, a recent report by the Dehradun-based University of Petroleum and Energy Studies said, could save $6.12 billion in oil import bill.

Besides producing bioethanol for the fuel blending ethanol for the fuel blending programme, the new refineries will provide additional income for farmers, create jobs in rural areas and help air quality management.

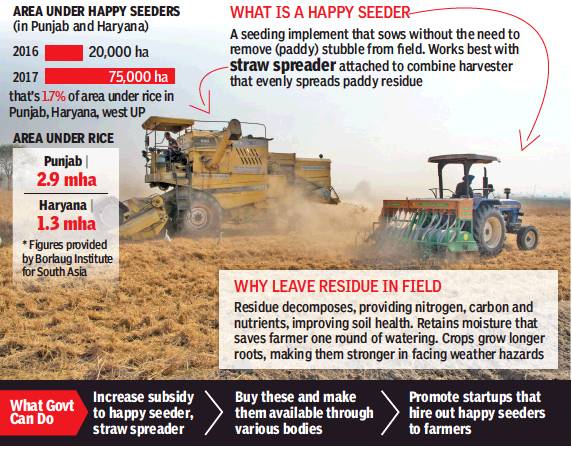

Happy Seeder, straw spreader

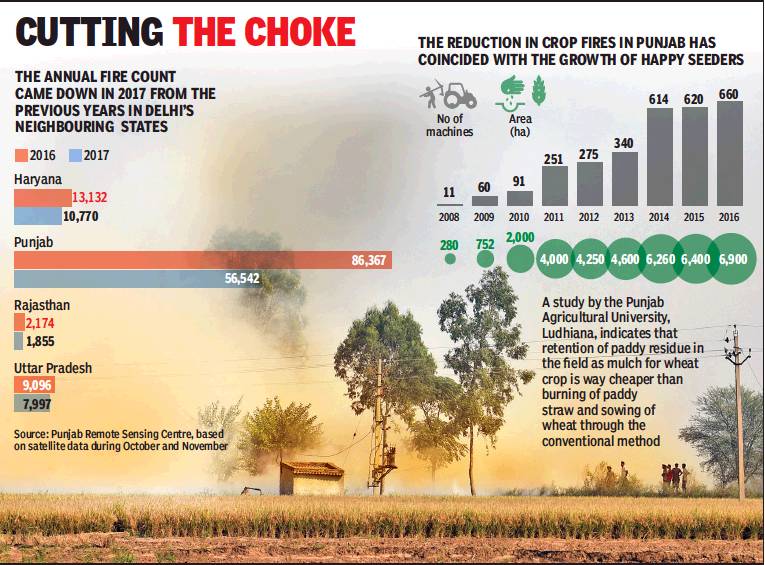

From: Amit Bhattacharya, 4-fold rise in green solution to burning of paddy stubble, December 18, 2017: The Times of India

Tech Is Proven, Needs Sop For Big Push: Experts

For the past two years, Manoj Kumar Munjial hasn’t set fire to a single straw of paddy residue in his fields sprawled over 45 acres at Taraori in Haryana’s Karnal district. Instead, the young farmer uses the straw as an input for future crops. Even as the new wheat crop grows, the old residue sits in the field enriching the soil, conserving water, nourishing the new plants and creating conditions for decreased use of fertilisers.

Welcome to the post-stubble-burning future. Munjial is among a growing tribe of farmers in Haryana and Punjab who are using paddy residue for greener agriculture. The technology has existed for years. But recent improvements, say experts, have made it a more viable and scalable solution to the vexed problem of stubble-burning. It registered an estimated four-fold increase this season, which is still less than 2% of the area under rice cultivation in northwest India.

The technology is a combination of Happy Seeder and straw spreader (straw management system or SMS) for rice-wheat farming. Developed by Ludhiana’s Punjab Agricultural University, the Happy Seeder is a machine that sows seeds without the need to till the field or remove paddy straw. It works best when the straw is spread evenly on the field through the SMS device attached to a combine harvester.

How this tech is a win-win for farmers, environment

Stubble Burning: Combination Of SMS & Happy Seeder Way Forward

In two years, I have recovered my Rs 1.05 lakh investment on Happy Seeder. Apart from my own farm, I hired it out on 120 acres of other farmers’ fields this year. Last year, that figure was 80 acres. Each acre gives me a return of Rs 800-900, after deducting diesel costs for running the tractor,” Munjial said.

According to estimates by the international non-profit research body, Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA), the use of Happy Seeders increased almost four times this sowing season over the previous year, with an estimated 75,000 hectares coming under it in Punjab and Haryana.

“The combination of straw management system (SMS) and Happy Seeder is a win-win for farmers and the environment. It does away with stubble-burning while increasing farmers’ profitability and promoting climate-smart agriculture. The spinoffs are significant — lower chemical load on soil, more crop per drop, reduction in CO2 emissions, better soil health, less weeds and sturdier plants with deeper roots. These benefits are scientifically documented,” said M L Jat, a senior scientist at BISA.

Despite the strides, the technology is not catching on fast enough to make a significant dent in stubble-burning. Even after rising concerns and a crackdown on cropburning, the area under Happy Seeders this season was just around 1.7% of the 4.3 million hectares under rice cultivation in Punjab, Haryana and west Uttar Pradesh.

Though there’s a subsidy of Rs 50,000 for SMS and Happy Seeder machines, these implements still cost over Rs 1lakh each. Experts say these technologies, including the reversible plough (for potato and vegetable farming after rice crop), need to be further incentivised and a major push needs to come from the Centre and state governments well ahead of next year’s burning season.

Sources say the matter was discussed at the PMO committee under PM’s principal secretary Nripendra Misra earlier this month. A policy brief prepared by the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences had proposed various multiple business models for popularising Happy Seeder and SMS. These include custom hiring of the implements through agricultural cooperatives, medium farmers such as Munjial and specialised startups. Farmer unions have demanded higher subsidies and proposed that government make the implements available through local bodies and cooperatives.

“We are prepared to scale up production of Happy Seeders for the next season but we need an early and clear signal from the government,” said Joginder Singh of Kamboj Mechanical Works, one of the major producers of the machine.

Kamboj sold around 200 Happy Seeders this season, up from 100 last year. Landforce, another big producer, reported sales of 400 this year, significantly higher than the 10-15 Happy Seeders the company sold in 2016.

Ploughing stubble back into the soil

Manish Sirhindi, October 19, 2018: The Times of India

Farmers in ‘model’ Punjab village don’t burn crop stubble, plough it back into soil

When smoke from burning paddy stubble was choking Delhi last year, a village near Nabha in Punjab was doing its bit to keep the air clean. Not a straw was burnt in Kalar Majra, where 60 families farm about 700 acres.

“The government chose our village as a model, and gave all the machinery needed to manage the crop residue,” says Bir Dalvinder Singh, a Kalar Majra farmer who persuaded his neighbours to heed the government’s call against burning stubble. The eco-friendly step earned praise from the National Green Tribunal.

Although there is no assistance from the government this year, about 70% of Kalar Majra has decided not to burn paddy stubble, with good reason. Ploughing it back into the soil is good not only for Delhi’s air but also the farmers’ bottom line.

Few know this better than Surjeet Singh of Sandhugarh village in Punjab’s Fatehgarh Sahib district. He hasn’t burnt crop residue on his 45 acres for the past 15 years. “I use a ‘happy seeder’ to manage the stubble, and for the last two harvests I used the straw management system of a combine harvester,” he said.

Surjeet had his moments of doubt when costs shot up in the first two years. “It appeared to be a bad decision,” he said, but he started saving on fertiliser and fuel from the third crop onwards. He claims his use of fertiliser has halved. “Despite that my crop yield has increased by at least 20%.” Parvinder Singh, of Mavi Kalan village near Patran, is another advocate of the happy seeder. It not only saves diesel at the time of tilling, but also water, as the fields don’t need irrigation before sowing.

Cost of giving up stubble burning too much for some

Yet the yield goes up by 2-2.5 quintals of wheat per acre, as the paddy straw acts as a crop nutrient,” Parvinder Singh said.

So, why do most farmers in Punjab still burn their crop residue? Bir Dalvinder, who used to be a techie in Gurugram and has braved Delhi’s yearly smoke episodes, says cost is the main hurdle. Jeet Mohinder of Kularan village in Patiala district agrees, saying residue management costs Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,500 per acre in the first two years. “Most farmers consider it a risk, and take the easy way out by burning the stubble.”

Pressure from farmers’ unions is another deterrent, says Bir Dalvinder. “Some marginal farmers have been misled by the kisan unions. They say they will burn the residue if the government does not provide help. But we are trying to persuade them not to fall for the misinformation campaign.”

The government has tried to encourage stubble management with subsidies on equipment, but Jeet Mohinder says it should give farmers financial benefits for the first three years instead. Once the decomposed stubble boosts soil fertility, “farmers will realise the benefits of not burning it. They will be eager to find ways to dispose of it in an environment-friendly way.”

Health issues

Study links straw burning to cancer, kidney damage

Crop residue fires in Pun jab and Haryana are en hancing concentrations of toxic gases like benzene and toluene, according to research from Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Mohali.

In the months right after the harvest of paddy , the levels of these gases were found to be 1.5 times higher than the annual average concentrations, according to a recent study that monitored air at a site in Mohali a few kilometres downwind of paddy fields, between 2012 and 14. Farmers set fire to crop residue after harvest, which sends massive plumes of smoke into the air.

The study also detected, for the first time, a compound known as isocyanic acid at annual average levels close to the toxic threshold of 1ppb (parts per billion). Exposures above this level can lead to cataracts and rheumatoid arthritis.

Annual concentrations of benzene, a known carcinogen, exceeded the National Ambient Air Quality Standard of India limits of 1.6ppb. Such benzene exposure could raise cancer risk by 25 per million children and 10 per million adults, the study estimated, at sites 10-15 km downwind of the fields.

The cancer risk would be even higher for farmers and villagers closest to the fields, the study said, adding that mitigating crop fires could reduce these risks.

The findings come from the first long-term field measurement in India of the impact of post-harvest agricultural fires on ambient levels of gases known as volatile organic compounds. The gases measured in the study include acetonitrile, benzene, toluene, and aromatic hydrocarbons. These substances have direct effects on human health -high levels of toluene can cause dizziness, eye irritation, kidney damage, for instance -but can also react with other substances to form secondary pollutants.

Unlike particulate matter, which gets filtered to some extent by the nose and throat, gases like benzene go straight into the lungs, said Vinayak Sinha, an associate professor at IISER's Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences who led the research team. The emission of isocyanic acid was of particular concern, he said. “This substance is related to methyisocyanate, which was emitted in the Bhopal accident, and is very dangerous,“ Sinha said.

Isocyanic acid is known to be produced by biomass burning, diesel exhaust and other sources. But its measurement as an environmental pollutant has only recently begun.

Sinha and others first identified the emission of benzene and related gases from harvest fires in 2013 by studying the effects of a single plume on a single night in 2012. The latest study , published recently in the journal `Environment International', quantifies the contribution of crop residue burning to the levels of these gases over multiple years.

Norms to administer the practice

Norms to curb crop residue going up in smoke

Vishwa Mohan, Norms on crop residue go up in smoke, Nov 09 2016 : The Times of India

2 States Violate Two-Year-Old Guidelines With Impunity

If Delhi's neighbouring states had adhered to the guidelines of the two-yearold national policy for management of crop residue (NPMCR), the national capital and other cities in the NCR would have been perhaps spared of current alarming situation of air pollution, attributed mainly to stubble burning.

After formulating the comprehensive national policy to deal with the issue of crop residue in November 2014, the Union agriculture ministry had even held a workshop on stubble burning in Chandigarh in January 2015. But such ef forts did not appear to move Punjab and Haryana -the two states where farmers contin ued to indulge in stubble burning in the post-harvest season.

Agriculture minister Rad ha Mohan Singh reviewed the issue on Tuesday and urged the states to promote use of equip ment for crop residue management in a big way . He also emphasised on creating awareness among farmers and exploring various incentives for them to switch over to ecofriendly measures to dispose of stubble. “The states have also been asked to encourage farmers to use all those machines for crop residue management which were distributed to them under various schemes in the past,“ said an official.

The review meeting was held in the backdrop of alarming air pollution in Delhi and neighbouring cities. Though pollutants from other sources contributed immensely to air pollution in the capital, stubble burning on a massive scale in Punjab and Haryana too turned out to be a key reason.

The 2014 national policy envisages adoption of technical measures, including diversified uses of crop residue, capacity building and training along with formulation of suitable legislation, to deal with the issue of disposing of stubble.

Reasons for continued practice

Ploughing Back Of Stubble Is Tedious, Costly

Jayashree Nandi, Why crop burning may continue this year too, April 22, 2017: The Times of India

Ploughing Back Of Stubble Is Tedious, Costly

A few patches of black disturb the golden spread of ripe wheat ready for harvesting in Haryana's Karnal district. These are tracts that were set on fire recently after the standing crop was reaped to ready the field for paddy planting in the monsoon. Many more fields will be set afire in a week or so when harvesting work ends in Punjab and Haryana. This year, however, such fires will be covert actions. Already farmers are claiming the field fires of recent weeks were accidental. Satellite surveillance by the Punjab government and stringent monitoring by Haryana government to prevent stubble burning have left farmers apprehensive.

Stubble burning is being discouraged for its massive pollution impact. For the moment though, despite wheat and paddy stubble burning destroying the soil and causing severe heat stress on farmland, the cultivators cannot change this farming tradition, they say. Subsidies for agri equipment, such as happy seeder or rotavor that can sow seeds without the need to remove the remains of the paddy stubble, haven't reached most farmers.Wheat farmers who can afford it use a reaper that costs around Rs 2 lakh. It only leaves a short stubble close to the ground that is burnt by most or ploughed back into the soil by some. Those who plough the stubble into the soil are not happy because, they claim, this method can damage the paddy seedlings. Plus, ploughing back is often labour and time intensive.

Satellite images show fires have just started in Punjab and Haryana, though Karan Avtar Singh, chief secretary of the state, insisted, “Only 5 to 10 incidents have been reported this season. Many panchayats have assured us of zero stubble burning.“

But Rattan Singh Mann, Haryana chief of Bharatiya Kisan Union, admitted, “We recently courted arrest when we set our fields on fire.“ He explained that wheat can be cut low to leave less stubble, but all alternatives to burning the rice stalks was too expensive.

Among the options, the stubble doesn't have many takers as fodder either. “Cattle don't eat stubble because of the frequent fuel spill during cropping,“ explained Ramanjaneyulu GV , executive director, Centre for Sustainable Agriculture.

At the root of the pollutioncausing problem is Punjab and Haryana's wheat-paddy combination. After harvesting paddy in October, burning the residue is the quickest way to prepare the field for wheat sowing in late October or November. “Rice cultivation should be banned in these regions, but not many agree with me,“ said Mann. Rice plant stubble is not the only problem, paddy requires a lot of water too. “Farmers here have to dig down 400 feet to get water,“ revealed Mahtab Kadyan, another farmer leader.

At Jundla village, Sulakhan Singh Kamboj argued, “We cannot plant replacement crops such as oilseeds or pulses unless the government procures our produce at good prices. Last year I planted peas that I finally sold at Rs 5 per kilo. That did not even cover the labour cost.“

Farmers with the Kheti Virasat Mission in Punjab are, however, gradually moving away from paddy . They claim not to burn the wheat stubble also, but “either make manure of it or mulch it“, according to Umendra Dutt, KVM member.

Recent NASA images show large fires in Madhya Pradesh and parts of east India. According to Ramanjaneyulu, these could be signs of forest fires, stubble burning or slash-and-burn cultivation. “Wheat stubble burning across the country is on the rise because getting labour to deal with it is tedious and expensive,“ he added.

Trends, impact on air quality

2017, Delhi, Haryana, Punjab

Crackdown By Punjab, Haryana Working So Far

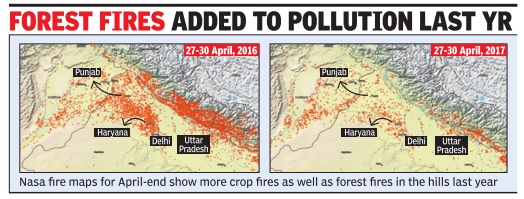

There has been an increase in burning of wheat crop stubble in Punjab and Haryana compared with the previous one, Nasa's satellite pictures reveal. But the images also reveal a larger and more significant trend -the practice of crop-burning is down sharply in comparison with the same period in 2016

Ground reports suggest the two state governments' firm approach seems to be working but major challenges lie in the days ahead as angry farmers demand a viable alternative to the practice. Nasa's FIRM web fire mapper, which uses satellite imagery to map instances of fires on the ground, shows a marked reduction in `fire spots' in 2017 over the previous year. The same eight-day period (April 27-May 4) was used to make the comparison.Burning of stubble after the kharif (October-November) and rabi (April-May) seasons is seen as a major contributor to pollution in the region. Air quality in Delhi is another indicator of re duced crop burning this year. A comparison of an eight-day AQI average (April 27-May 4, both days included) of 2016 and 2017 shows air in the capital this year has been far healthier than the last.AQI during the period this year has been in the moderate zone (176) while it was `very poor' last year at 307. Of course, weather conditions as well as raging forest fires in Uttarakhand also contributed to air pollution in Delhi last year.

Last year's pattern, as seen in the satellite images, reveals that crop-burning peaked in the first week of May and started abating around May 12. This would suggest that there could yet be a spike in crop fires.

There are mixed reports from the ground on cropburning. “Farmers are afraid to burn their wheat stubbles this year because of the ad ministration's threat of action and fines,“ Ruby Singh Sandhu, a farmer from Ellenabad in northwest Haryana, said on phone.

In Punjab, many farmers have been protesting against the tough orders on cropburning. At many places, farmers have been openly defying the directions and burning the straw, despite the theat of cases and fines.

Farmers are demanding a compensation of Rs 2,000 per acre and eight-hour power supply to help prepare the fields through farm machin ery without burning straw.They have threatened to start burning wheat stubble collectively from May 10 if the demands aren't met.

Wheat was sown in nearly 35 lakh hectares in Punjab and state expects a bumper harvest this year. The state pollution control board, agriculture department and the districts are keeping a watch over burning of straw through remote sensing.Nearly 200 farmers have been fined in various districts till May 3. On Thursday , seven farmers were fined Rs 17,500 for burning straw in Muktsar district. The state has fixed a fine of Rs 2,500 for burning straw in fields up to 2 acres, Rs 5,000 for farms up to 5 acres and Rs 15,000 for those over 5 acres. Most of the fines slapped so far have been on fields below 5 acres, said a state government official.

“The Adesh institute of medical sciences and research (AIMSR) had in January 2016 carried out an extensive study to document the health impacts of stubble burning and found that smoke caused by burning of agriculture waste was adversely affecting the quality of life of farmers. It showed that nearly 85% people from all age groups suffered from one or the other health problems because of the smoke,“ said Vittul K Gupta, associate professor at AIMSR.

An agriculture department official said the state government has offered up to 50% subsidy on various implements as an alternative to straw burning. “We have even demanded suggestions from farmers for measures to be adopted to contain menace of straw burning,“ he said.

2017, May: stubble burning in Punjab rise sharply

The use of geo-spatial data and satellite imagery to crack down on farmers resorting to stubble burning has not changed things much on the ground in ending this practice.In fact, the number of crop burning cases has shot up from 1,553 to 13,054 in the last eight days -an over eight-time jump -with the end of the harvesting period.

The official figures accessed show that as on May 11, the cumulative number of crop firing cases reported by Punjab Remote Sensing Centre, was 12,370, while 684 cases were detected by other means. Sources in the Punjab Pollution Control board told TOI that they were finding it difficult to initiate action against violators.

The year-wise position

Punjab: 2008-2016; 4 states: 2016-2017

Jayashree Nandi, Delhi pins hopes on neighbours for clean air, April 8, 2018: The Times of India

the Punjab, 2008-2016;

Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, UP: 2016-2017

From: Jayashree Nandi, Delhi pins hopes on neighbours for clean air, April 8, 2018: The Times of India

As Central Farm Subsidy Kicks In, All Eyes On Other States To Reduce Stubble Burning

This year will be a test case for curbing cropstubble burning in states neighbouring Delhi and whether this will improve air quality in the capital.

The Centre — having decided on an “in-situ management” of crop residue as opposed to collecting paddy straw to use as fuel in power generation or convert it products like bio-char used as fertiliser — has allocated funds to the affected states to subsidise farm machinery that can prevent stubble burning.

The Centre allocated Rs 1,140.3 crore for a sub-mission on agriculture mechanisation in this year’s Union budget, substantially hiking the funds from Rs 525 crore in 2017-18. NCR states are now rolling out the scheme. D K Behera, director, agriculture department, Haryana, told TOI, “Under the new scheme, we will promote custom hiring centres set up by farmer groups but will also cater to individual far mers.”

Haryana has been allocated Rs 216 crore and Punjab, Rs 365 crore for the scheme. “We will encourage farmers groups and cooperative societies rather than individual farmers to buy or rent this machinery. This approach will avoid financial liability and loans,” said Viswajit Khanna, additional chief secretary, agriculture, Punjab.

A sub-committee of the task force on prevention of stubble burning in Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh constituted by the cabinet secretariat submitted its final report to the Supreme Court in January. It advised that in-situ mechanisation allowing use of crop stubble as mulch was more cost effective than removing the plant remains. It also recommended large scale production of such machinery and their positioning in villages before September 2018.

A Niti Aayog-CII report had suggested alternatives to crop-residue burning, including ex-situ management processes. The cabinet secretariat panel, however, observed, “Bio-char production requires collection of paddy straw and its treatment in the field in temporary kilns. This option would require financial support of 9-10% of the minimum support price. Ex-situ options identified by Niti Aayog-CII require significant capital and operating subsidy to become sustainable.”

The central sub-committee instead recommended zero tilling machines for wheat, with paddy straw as mulch. To achieve this, every combine harvester would need to have a separate straw management system a cutter, spreader and a happy seeder. Use of these components as a package would solve the wheat sowing problem, the report assured. For planting of potato, peas and other vegetable crops, incorporation of paddy straw and its fast decomposition could be achieved using the Rotavator and mould board (MB) plough developed by the Punjab Agricultural University.

The sub-committee suggested the government could provide a flat subsidy of 50% of machinery cost to individual farmers or a subsidy of 75% of machinery cost to cooperative societies, custom hiring centres, farmer’s interest groups and gram panchayats.

The Supreme Courtmandated Environment Pollution Control Authority, which is overseeing the enforcement of the court’s directions on curbing air pollution in NCR, has endorsed the sub-committee’s report, but agriculture experts worry that this may not do much to resolve the ecological woes of farmers. While the main reason for the crop stubble burning is the very small window of 20 days between harvesting of paddy and sowing of wheat, experts said there are other problems related to wheatpaddy combination, including extreme water stress and reliance on pesticides.

“We have to understand that the rice-wheat system has problems,” said G V Ramajaneyulu, executive director, Centre for Sustainable Agriculture. “Instead we should opt for wheat-pulses or rice-legumes or vegetablelegumes combinations. Crop stubble burning is just a symptom of this problem and even this is being addressed only because of pollution in Delhi. But the intensive ground water depletion and water contamination due to high chemical usage in the rice-wheat system is not being addressed.”

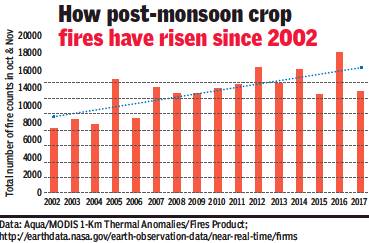

2002-17, an increase

From: Jayashree Nandi, Nasa data shows no reduction in crop fires, 2016 worst yr, December 16, 2017: The Times of India

Crop fires have steadily increased in Punjab and Haryana since 2002, an analysis of Nasa satellite data suggests, contradicting official claims that a number of policies have been implemented to curb the practice of paddy stubble burning.

A study by Nasa research scientist Hiren Jethva found that crop fires are on the rise, with the highest number of hotspots detected in 2016. Jethva’s research also suggests that the increase in crop fires (about 500 per year between 2002 and 2016) could be linked to rising crop production in the region.

He analysed data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor on Aqua satellite to track annual crop fire numbers. In his blog on the Nasa Earth Observatory website published in early 2017, Jethva also analysed normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI) — a measure for greenness that can indicate crop or vegetation cover.

“There seems to be a oneon-one relationship in NDVI measured by the MODIS sensor prior to harvest (September) and the total number of fire hotspots observed during the harvest season (October and November). This suggest that the increase in the number of fires is likely related to increasing crop production,” the blog says.

Jethva also refers to data from the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, department of agriculture, which says post-monsoon, rice crop production has increased at a linear rate of 0.18 million tonnes from 2002 to 2016 in Punjab. On November 5 last year, Delhi had suffered its worst smog episode in 17 years with average PM2.5 levels 14 times the 24-hour standard. In October-November last year, there were nearly 18,000 crop fires in Punjab and Haryana put together — the highest since 2002. The number of fires reduced in 2017 — to a little more than 12,000 — but still had a huge impact on air quality in NCR, according to experts.

The impact of crop fires on air quality is accentuated by hostile meteorological conditions. During this smog episode, for example, ground wind speed was very low on most days, but wind direction was from north and northwest through Punjab and Haryana where crop stubble is being burnt over large stretches.

IMD said mixing heights (also called boundary conditions) — the levels at which ground level winds mix with the higher winds and allow dispersion — has been extremely low, leading to a high concentration of pollution particles. But crop fires are also ruining soil health and depleting groundwater resources massively in these states. According to Ramanjaneyulu G V, executive director at Centre for Sustainable Agriculture, burning also leads to an immediate decline in the bacterial and fungal population in the top 2.5cm of the soil.

Repeated burning permanently diminishes the bacterial population by more than 50%, increasing farmers’ dependence on fertlisers and pesticides. He added that the problem of crop stubble burning started increasing since 2002. “The depletion of groundwater levels made Punjab come up with a law in 2009, which makes sowing of paddy before June 15 a criminal offence. The law allows agriculture department officers to destroy the nursery or transplanted paddy. The uprooting costs are to be borne by farmers. The Act levies a penalty of Rs10,000 per hectare per month on the farmers who contravene it. It even allows field officers to disconnect power supply to a farmer’s field till the notified date if the farmer is found violating the law repeatedly. This left a very small window for farmers between kharif harvest and rabi sowing, forcing them to resort to burn off,” Ramanjaneyulu said. He added: “The prices of paddy have not increased in the last 10 years. As a result, farmers also felt spending more amount on removal of stubbles is not economically viable … so they burn off.”

Farmers from various farmer groups, including the Bharatiya Kisan Union, say an important factor could be increasing labour costs, which have led to more farmers taking up mechanised harvesting by using combines to harvest both paddy and wheat.

Many farmers say they want to give up paddy cultivation, but can’t — because procurement prices for other crops are not fair.

“Solutions lie in finding uses for the stubble and assigning real economic value to it, so that burning is an economic loss to the farmer. Solutions are well known, in terms of infield use as manure to reduce fertilizer cost or generate power, or make fuel and material. But there is no clear strategy to build business cases around these solutions to scale or provide support to farmers to use this as manure,” said Anumita Roy Chowdhury, head of Centre for Science and Environment’s clean air campaign.

See also

Crop stubble burning: India

Fire accidents (accidental fires): IndiaThis page includes data on all categories of fires, including forest fires and the burning of crop residue