Internet, the worldwide web and India

(→2012-15, India had world’s most first-time internet users) |

|||

| Line 230: | Line 230: | ||

The UNCTAD report has also raised the concern of how companies, organisations, governments and individuals will need to pay more attention to protect their online data and devices as more economic activities go digital. | The UNCTAD report has also raised the concern of how companies, organisations, governments and individuals will need to pay more attention to protect their online data and devices as more economic activities go digital. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2014-17: prices fall, speed and usage increase rapidly== | ||

| + | [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F06%2F03&entity=Ar00319&sk=40434442&mode=text Pankaj Doval, Rising speed, falling prices make Indians gorge on data, June 3, 2018: ''The Times of India''] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File: 2014-17- prices fall, speed and Internet usage increase rapidly.jpg|2014-17: prices fall, speed and Internet usage increase rapidly <br/> From: [https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/TimesOfIndia/shared/ShowArticle.aspx?doc=TOIDEL%2F2018%2F06%2F03&entity=Ar00319&sk=40434442&mode=text Pankaj Doval, Rising speed, falling prices make Indians gorge on data, June 3, 2018: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''People Switch To Smart TVs, Streaming'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Indians are chugging data like never before. In just three years from 2014, monthly data usage in the country increased 15 times, as smartphones and mobile internet became cheaper and faster. At the end of 2014, the average monthly data consumption was only 0.26GB per person, which increased to over 4GB at the end of 2017, Trai figures show. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Usage has increased not only because fast 4G data is now very cheap, but due to sources of content for smartphones having multiplied. Most online videos are seen on smartphones, and a study by media analytics company Comscore shows 89% of Indians go online on phones and tablets — the highest share among large data-consumption economies. 4G, which promises speeds of at least 10Mbps, is the main driver of wireless data consumption, accounting for nearly 82% of total usage last year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Data prices tumble to ₹19 from ₹269 per GB in 2014''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4G data prices have fallen from an average of Rs 269 per GB in 2014 to Rs 19 now — and even lower in case of bundled individual data packs. It’s 7% of what customers paid earlier. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prices dropped sharply after Reliance Jio, which has a 4G-only business model, launched in September 2016. However, with rising internet usage, rival companies like Airtel, Vodafone, Idea Cellular and BSNL have also expanded their 4G network. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Increasing wireless data consumption has been a boon for streaming services like YouTube, Gaana and Hotstar. Some, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, have even started commissioning and sourcing content in Hindi and other Indian languages. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sales of “smart” or internet-ready TVs are also up. Rahul Tayal, a director at LG India, said smart TVs make up 40% of their TV sales now. Many TVs now come with apps such as Netflix, YouTube and Hotstar and consumers mirror-cast from their smartphones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Not only data but also voice calls have increased after a dip. To keep up with Jio’s offering of free calls, competing operators have come up with their own schemes, effectively reducing voice prices to nil in case of bundled data offers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Higher usage has not meant higher revenues and profitability for the companies. The average revenue per user (ARPU) — a key measure of a telecom company’s health — has been for GSM players from Rs 117 at the end of 2014 to around Rs 80 at the end of 2017. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The pressure is telling on older telecom players even as Jio remains aggressive and reports profits. Airtel, the country’s biggest mobile operator, has seen a decline in profitability since Jio’s launch and suffered its first loss (in Indian operations) during the January-March period this year. | ||

==2016: Rural India saw 22% jump in internet use in one year: Unicef== | ==2016: Rural India saw 22% jump in internet use in one year: Unicef== | ||

Revision as of 20:39, 4 June 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Access

State-wise position, 2016

See graphic.

Cybersquatting/ domain name complaints

2015: India no.11

The Times of India, Apr 20 2016

Indian domain name plaints up 60% in 2015

Rupali Mukherjee

German luxury fashion firm Hugo Boss leads the list of global companies which filed the highest number of cybersquatting cases in 2015, with fashion emerging as the sector with the greatest activity in terms of domain name complaints, according to data from World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). While US heads the list of countries with the largest number of cases at 847, India notched a total of 59 domain name complainant cases in 2015, registering a growth of nearly 60%.

Domestic companies including Bharti Airtel, Voltas, Tata Sons, Wipro, Aircel and Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation are among those who filed cybersquatting complaints in 2015.Simply put, cybersquatting is the abusive registration of trademarks as domain names, where an individual or company attempts to usurp the reputation of the domain name of an established brand online.

“Whereas Indian trademark owners filed 30 cybersquatting cases with WIPO in the year 2010, they filed almost twice that number in 2015 (59). In India, as elsewhere, cybersquatting targets include famous brands as well as smaller enterprises in banking, automotive, telecommunications, energy , e-commerce, and a range of other sectors. By combating cybersquatting, these brand owners help Indian consumers to find authentic web content,“ Erik Wilbers, director at WIPO's Arbitration and Mediation Center, told.

It is important to prevent cybersquatting, particularly with the opening up of markets and growth of e-commerce, because it may lead to confusion and, in some cases, even fraud. WIPO director general Francis Gurry said in a statement, “As brand owners face the possibility of further abuse of their trademarks in domains -both old and new -they continue to rely on WIPO's cybersquatting dispute resolution procedures. By combating opportunistic domain name registration practices, WIPO's services help consumers to find authentic web content, and enhance the reliability of the domain name system.“ Hugo Boss was followed by tobacco firm Philip Morris, and consumer durables company AB Electrolux among the largest companies which filed cybersquatting complaints. The top three sectors that filed the largest number of cybersquatting complaints globally were fashion (10%), banking & finance (9%), and internet & IT (9%).Retail, biotech & pharmaceuticals, automobiles, and food were the other industries that filed these complaints.

The process to register a domain name is much simpler than registering a trademark, and also cheaper. This is cited as a reason for the huge growth in domain name disputes. Interestingly, in addition to the largest-used “legacy“ domain names like .com by companies, the newer ones .xyz, .club and .email are becoming popular too. The increase in new ge neric top-level domains (gTLD) registrations in WIPO's caseload is anticipated to continue. ICANN, the body that manages domain name system registration, has been rolling out new gTLDs (alternatives to `.com'). As these increase in number, so does the potential for cybersquatting, an industry expert says.

In an instance of alleged cybersquatting, companies file a case with WIPO, which appoints a panelist to assess whether the case is indeed cybersquatting or not. The Uni form Domain-Name-Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), proposed by WIPO in 1999, is accepted as an international standard for resolving domain name disputes outside the traditional courts, and is designed specifically to discourage and resolve the abusive registration of trademarks as domain names, commonly known as cybersquatting.

Under the UDRP , a complainant must demonstrate that the disputed domain name is identical or confusingly similar to its trademark, that the respondent does not have a right or legitimate interest in the domain name, and that the respondent registered and used the domain name in bad faith.

Censorship of Websites : India

Pranesh Prakash , Internet Rights & Wrongs “India Today” 1/9/2016

Over the last few weeks, there have been a number of cases of egregious censorship of websites in India. Many people started seeing notices that (incorrectly) gave an impression that they may end up in jail if they visited certain websites. However, these notices weren't an isolated phenomenon, nor one that is new. Worryingly, the higher judiciary has been drawn into these questionable moves to block websites as well.

Since 2011, numerous torrent search engines and communities have been blocked by Indian internet service providers (ISPs). Torrent search engines provide the same functionality for torrents that Google provides for websites. Are copyright infringing materials indexed and made searchable by Google? Yes. Do we shut down Google for this reason? No. However, that is precisely what private entertainment companies have done over the past five years in India. Companies hired by the producers of Tamil movies Singham and 3 managed to get video-sharing websites like Vimeo, Dailymotion and numerous torrent search engines blocked even before the movies released, without showing even a single case of copyright infringement existed on any of them. During the FIFA World Cup, Sony even managed to get Google Docs blocked. In some cases, these entertainment companies have abused 'John Doe' orders (generic orders that allow copyright enforcement against unnamed persons) and have asked ISPs to block websites. The ISPs, instead of ignoring such requests as instances of private censorship, have also complied. In other cases (like Sony's FIFA World Cup case), courts have ordered ISPs to block hundreds of websites without any copyright infringement proven against them. High court judges haven't even developed a coherent theory on whether or how Indian law allows them to block websites for alleged copyright infringement. Still they have gone ahead and blocked.

In 2012, hackers got into Reliance Communications servers and released a list of websites blocked by them. The list contained multiple links that sought to connect Satish Seth-a group MD in Reliance ADA Group-to the 2G scam: a clear case of secretive private censorship by RCom. Further, visiting some of the YouTube links which pertained to Satish Seth showed that they had been removed by YouTube due to dubious copyright infringement complaints filed by Reliance BIG Entertainment. Did the department of telecom, whose licences forbid ISPs from engaging in private censorship, take any action against RCom? No. Earlier this year, Tata Sky filed a complaint against YouTube in the Delhi High Court, noting that there were videos on it that taught people how to tweak their set-top boxes to get around the technological locks that Tata Sky had placed. The Delhi HC ordered YouTube "not to host content that violates any law for the time being in force", presuming that the videos in question did in fact violate Indian law. They cite two sections: Section 65A of the Copyright Act and Section 66 of the Information Technology Act. The first explicitly allows a user to break technological locks of the kind that Tata Sky has placed for dozens of reasons (and allows a person to teach others how to engage in such breaking), whereas the second requires finding of "dishonesty" or "fraud" along with "damage to a computer system, etc", and an intention to violate the law-none of which were found. The court effectively blocked videos on YouTube without any finding of illegality, thus once again siding with censorial corporations.

In 2013, Indore-based lawyer Kamlesh Vaswani filed a PIL in the Supreme Court calling for the government to undertake proactive blocking of all online pornography. Normally, a PIL is only admittable under Article 32 of the Constitution, on the basis of a violation of a fundamental right (which are listed in Part III of our Constitution). Vaswani's petition-which I have had the misfortune of having read carefully-does not at any point complain that the state is violating a fundamental right by not blocking pornography. Yet the petition wants to curb the fundamental right to freedom of expression, since the government is by no means in a position to determine what constitutes illegal pornography and what doesn't.

The larger problem extends to the now-discredited censor board (headed by the notorious Pahlaj Nihalani), as also the self-censorship practised on TV by the private Indian Broadcasters Federation (which even bleeps out words and phrases like 'Jesus', 'period', 'breast cancer' and 'beef'). 'Swachh Bharat' should not mean sanitising all media to be unobjectionable to the person with the lowest outrage threshold. So who will file a PIL against excessive censorship? F

Pranesh Prakash is a Policy Director at the Centre for Internet and Society

Digital divide

1995-2002

The Times of India Jan 08 2015

India saw its first internet connection on August 15, 1995 when Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited launched the country's first internet services. The government opened up the sector for private operators in 1998. New regulations in telecom policy opened up internet telephony in 2002. Despite these measures, India's internet prevalence is far lower than in the advanced or other BRICS economies. Given the literacy levels and with average revenues per user in many cases being comparable to the cost of the cheapest internet packages offered, this is hardly surprising.

2017/ digital divide, state-wise

Rural Kerala frontrunner in Internet access, rural Bengal at the bottom of the heap

The southern State of Kerala seems far ahead of all Indian States in breaching the digital divide, if the data generated by Pratham’s Annual Status of Education Report, 2017, for its sample district of Ernakulam are to be believed.

And the eastern State of West Bengal seems right at the bottom in terms of the rural youth’s access to the Internet, computers and mobiles, as per data generated from its South 24 Parganas district.

Even as the government looks at ushering in a Digital India, ASER 2017 offers a snapshot into how different States are faring in breaching the digital divide, by focusing on rural youth in the 14-18 age group in 28 rural districts across 24 States in India.

A pointer

The patterns may not hold true or all districts in particular States, but may be a pointer to the south’s lead and the eastern States’ backwardness in rural digital access.

Significantly, 69.8% of the rural youth surveyed in Kerala’s Ernakulam district had used the Internet in the week before the survey. Similarly, 92% had used mobile phones and 60% had used computers in the week leading to the survey. It was also the only district among those surveyed across India where a third of the rural youth had used an ATM.

The surveyed districts of Amritsar and Bhatinda and Maharashtra’s Satara and Ahmednagar also showed decent digital access, though well below Kerala.

West Bengal lay at the other end of the spectrum, faring worst in breaching the digital divide.

Just 17.1% of the rural youth between 14 and 18 in West Bengal’s South 24 Parganas district had used the Internet in the week leading to the survey. Just 21.2% had used a computer and 65.5% had used a mobile phone.

Never used

In Kerala’s Ernakulam, just 10.5% of the surveyed rural youth had never used the Internet and 0.4% had never used a mobile phone.

The situation was much worse in eastern States, however.

While nationally, 63.7% of the rural youth surveyed had never used the Internet, the figures were much higher in districts in West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand and Assam.

In West Bengal’s South 24 Parganas district 74.4% rural youth in the age group of 14 to 18 years had never had access to Internet while in Odisha’s Khordha district, the number was 65.8%. In Jharkhand’s Purbi Singhbhum the figure stood at 68.8% and in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur district 67.5%. In Assam’s Kamrup district the number was 64.1%.

Economics: The internet economy

2015-16: Apps added Rs 1.4 lakh crore to GDP

Internet apps added Rs 1.4 lakh crore to India's GDP in 2015-16, says a study released on Friday . It expects the figure to grow to Rs 18 lakh crore by 2020. Union minister of communications Manoj Sinha, who released the study on Friday , said since data is going to drive the industry more than voice, the ministry has also initiated a move to relook at the current Telecom Policy through public consultation.

The study , conducted by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (Icrier) and the Broadband India Forum, finds that nearly half of the contribution of the internet to the economy would be due to apps.

“The internet economy could contribute up to $537.4 billion to India's GDP in 2020, of which a minimum of $270.9 billion could be attributed to apps,“ says the study , using various economic analyses and logical regression models to isolate and calculate the impact of apps on the Indian economy . It has evaluated this impact across 19 telecom circles (India has 22) which are contiguous with state boundaries. The study is called “Estimating the value of new generation internet bases applications in India.“

“Since not all Internet usage is app based, we moderate the estimate using assumptions on contribution of apps to the Internet economy in India,“ says the study. Apps or applications, are mostly used on smartphones, to perform specialized tasks. The study measures internet usage on the basis of the “virtual networking index“ forecasts of IT company Cisco.

“From a CISCO estimate, India's Internet traffic from non-PC devices was 28% of total Internet traffic in 2015. According to experts, 70% of mobile or non-PC traffic could be attributable to apps implying that apps contributed a minimum of $20.4 billion to India's economy in the year 2015-16,“ says the study , adding that this estimate is based only on internet-based apps. Including offline apps here can swing the figure higher.

The Icrier forecasts are based on the assumption that today's “internet economy“ will remain the same in 2020.Newer apps, or new technology can skew the numbers. “In any case,“ says the study , “we can be sure that the Internet economy will magnify to at least 15% by 2020, with apps contributing at a minimum half of the value.“

Mobile Internet

Apps used the most in 2017

Sep 14 2017: The Times of India

See graphic:

Most popular app categories in India in 2015; Number of mobile phone users in India; Distribution of online shoppers in India by gender, 2015

Number of mobile phone users in India;

Distribution of online shoppers in India by gender, 2015; Sep 14 2017: The Times of India

Indians are known to be hands-on shoppers, the ones that like to touch and assess a product and haggle its price before making a purchase. The hunt for bargains has now moved to the internet and Indians are lapping it up, with shopping apps taking the largest share of downloads in 2015. Add to that the growing base of smartphone users in India and it's easy to see why up is where mobile commerce is headed in India

Net freedom

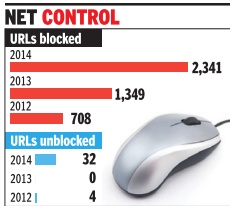

2014: Govt blocked 2,341 URLs, a 73% rise

Apr 4, 2015

Govt blocked 2,341 URLs in '14, 73% more than '13

The government issued orders to block 2,341 URLs in 2014, the official response to an RTI application has shown, up 73% from the number blocked in 2013. The RTI was filed by Delhi-based nonprofit legal services organisation Software Freedom Law Center India (SFLC.in) last month with the Department of Electronics and Information Technology (DeitY), which falls under the ministry of communications and IT.

The number of orders blocking URLs (Uniform Resource Locators), the address of data available on the world wide web, stood at 1,341 in 2013. The application sought answers on blocking orders issued pursuant to court orders, requests from government departments, and at the suggestion of private parties. The DeitY response says that “barring a few numbers, all URLs were blocked on the orders of the court.“ “Further, as per the provisions of Rule 16 of the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguard for locking for Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009, notified under section 69 A of the Information Technology Act 2000, the requests and complaints received and ac tions taken thereof are confidential,“ the reply adds.

SFLC.in, which uploaded the RTI and the reply on its website, has said in an accompanying blog that the government needs to review its stance on confidentiality, particularly in the light of the apex court's observations while striking down Section 66 A of the IT Act. It says that the SC “invited attention to several safeguards incorporated into Section 69A -one amongst them being that reasons behind blocking orders are to be recorded in writing in the orders... so that they may be challenged by means of writ petitions...“

2016-17: India was ‘partly free’

From: November 19, 2017: The Times of India

See graphic:

Net freedom index, in 2016-17 India was ‘partly free’

Shutdowns

2012- May 2017

`20 internet shutdowns in India in 2017', June 17, 2017: The Times of India

India has seen 20 instances of internet shutdowns in 2017, according to legal services organisation Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC). In June itself, there were temporary shutdowns in parts of Madhya Pradesh, and in Nashik, Maharashtra after farmer protests escalated. Reacting to the spate of shutdowns, international watchdog body Human Rights Watch on Friday called for Indian authorities to “cease arbitrary restrictions of the country's internet and telecommunications networks.“

SFLC has been tracking Internet shutdowns in India with their website internetshutdowns.in. It recorded 31 instances of internet shutdowns in the country in 2016. Between 2012 and now, it has recorded 79 internet shutdowns in India of varying types and duration.

“Of the 73 shutdowns recorded since 2012, 37 were preventive in nature i.e. imposed in anticipation of a law and order problem, while 36 instances were reactive in nature i.e. imposed in response to an ongoing law and order problem,“ says an analysis on internetshutdowns.in. 27 of these 73 shutdowns, it says, lasted for less than a day.

“Authorities' concerns over the misuse of the internet and social media should not be the default option to prevent social unrest,“ said Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director, Human Rights Watch.

Speed (download)

2015

See graphic, 'India and the world: Speed of internet connections, 2015'

2017: India 119th among 189 countries

From The Times of India, October 6, 2017

See graphic:

Fastest and slowest countries to download movies

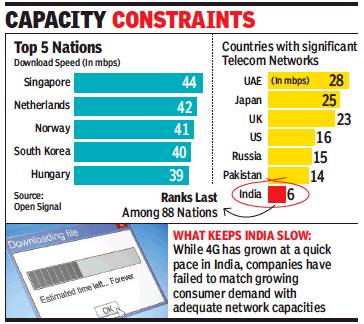

2018: 4G speed in India slowest in world

Pankaj Doval, 4G speed in India slowest in world, February 22, 2018: The Times of India

From: Pankaj Doval, 4G speed in India slowest in world, February 22, 2018: The Times of India

Lags Pakistan, Algeria, Kazakhstan, Tunisia

India may be going digital, but high-speed internet on mobile phones still remains a challenge, even on 4G. Despite telecom companies announcing massive rollout of 4G services, the average network speed in India remains the slowest across countries having substantial telecom networks, lagging even Pakistan, Algeria, Kazakhstan and Tunisia.

According to a list prepared by mobile analytics company OpenSignal, 4G download speed in India is the slowest across 88 countries spanning six continents. This is despite the fact that 4G has been expanding at a rapid pace across the country, and networks are being upgraded from slower 2G services.

On an average, the 4G speed in India has been measured at 6 mbps (actual experience could be much lower), whereas subscribers in neighbouring Pakistan enjoy internet at a more than double speed of 14 mbps. Algeria is ranked second-last at 9 mbps.

According to OpenSignal, subscribers in Singapore get the fastest downloads on 4G at 44 mbps, followed by the Netherlands at 42 mbps. In Norway, the 4G download speed is 41 mbps, while South Korea gets 40 mbps. OpenSignal analysed more than 5,000 crore measurements (collected between October 1 and December 29 of 2017) of speed from over 38 lakh smartphone and tablet users across six continents.

Giving out reasons for a slower network speed in India despite a wider 4G reach, the study blamed capacity constraints on network. Though 4G is available for around 86% of the time people access the internet, “4G networks lack the capacity to deliver connection speed much faster than 3G”, it said.

The telecom industry in India is staring at a financial nightmare, with most of the companies either deep in the red or just managing to stay profitable. The onslaught of fierce competition from 4Gonly Reliance Jio saw Vodafone and Idea Cellular slip into losses, while Airtel saw profits shrink massively.

Companies that provide network infrastructure to mobile companies said in private that most of the operators are slow in making fresh investments for augmenting capacities. “The sector is in a financial mess. We have seen slippage in investments, which are drying up due to losses,” one of the top infrastructure providers said, requesting anonymity.

While Jio has launched pan-India 4G services, others were literally forced to follow suit. Airtel is also giving 4G on a pan-India basis, while Idea Cellular covers the country, except Delhi and Kolkata. Vodafone is currently giving the service in 17 circles.

Subscribers complain that they “do not get promised 4G download speeds”, although companies make tall promises. “Internet is often very slow, and buffers on many instances,” a customer of a top telecom company said.

Concerns over poor service and slower speed have also been raised by the government, as it has started offering a variety of services online and is pushing digital payments in a big way.

Telecom secretary Aruna Sundararajan has said the government is mindful of the slow internet speed experienced by internet users in many parts of the country.

Rajan Mathews, DG of industry body Cellular Operators Association of India, said it is wrong to blame telecom companies for poor services. “Average spectrum holding by companies in India is around 26 MHz compared to 50 MHz across top economies.” Also, he said telecom companies face problems in laying optical fiber as well as deploying towers.

Usage of the Internet

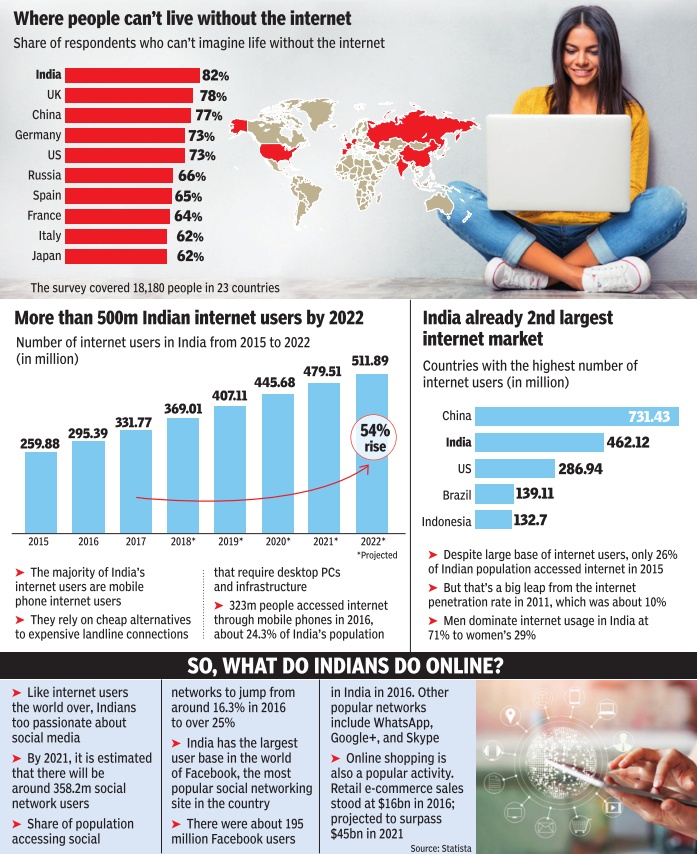

2012-15, India had world’s most first-time internet users

From: Dipak Dash, `From '12 to '15, India had highest No. of first-time internet users', October 29, 2017: The Times of India

India saw the highest number number of people going online for the first time during 2012-15 period among all countries, according to a recent report of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). About 17.8 crore people went online during this three-year period, which is much more than that of China, Brazil, Japan and neighbouring countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The report titled “Measuring the Evolving Digital Economy“ was released last week indicate that this trend of more people going online will spur purchase of goods and services resulting in greater inclusion and involvement of citizens with the government and economic growth.

“Nearly 90% of the 750 million people that went online for the first time between 2012 and 2015 were from developing economies, with the largest numbers from India (178 million) and China (122 million),“ the report said. The findings will come as a big boost to the government at a time when it's pushing for digital literacy and promoting doing things digitally .Government sources said the number of people going online must have gone up in the past two years.

The report says in India, Mexico and Nigeria, the annual growth rates of internet use were between 4-6% from 2012 to 2015, whereas the growth rates have been much slower in developed economies, except for Japan, as the markets have already reached near saturation.

According to the report, in many developing countries, nearly half or more of the internet users went online for the first time in the last three years, as in Bangladesh, India, Iran and Pakistan. In Brazil and China, more than 50% people used the internet whereas in India only slightly more than a quarter use it.

“The next billion internet users will also be primarily from developing economies,“ the global report said.

Projecting trends of the future, the report said people doing online transactions will shift from traditional debit and credit cards to new methods of payment. “Their share is expected to drop to 46% by 2019, as e-wallets and other alternative payment methods (such as mobile money) gain in importance. In developed regions, digital payments are dominated by credit and debit cards, followed by e-wallets. In developing countries, by contrast, credit cards are rarely the most important payment method for e-commerce, and the uptake of digital payments is often low,“ the report said.

The UNCTAD report has also raised the concern of how companies, organisations, governments and individuals will need to pay more attention to protect their online data and devices as more economic activities go digital.

2014-17: prices fall, speed and usage increase rapidly

From: Pankaj Doval, Rising speed, falling prices make Indians gorge on data, June 3, 2018: The Times of India

People Switch To Smart TVs, Streaming

Indians are chugging data like never before. In just three years from 2014, monthly data usage in the country increased 15 times, as smartphones and mobile internet became cheaper and faster. At the end of 2014, the average monthly data consumption was only 0.26GB per person, which increased to over 4GB at the end of 2017, Trai figures show.

Usage has increased not only because fast 4G data is now very cheap, but due to sources of content for smartphones having multiplied. Most online videos are seen on smartphones, and a study by media analytics company Comscore shows 89% of Indians go online on phones and tablets — the highest share among large data-consumption economies. 4G, which promises speeds of at least 10Mbps, is the main driver of wireless data consumption, accounting for nearly 82% of total usage last year.

Data prices tumble to ₹19 from ₹269 per GB in 2014

4G data prices have fallen from an average of Rs 269 per GB in 2014 to Rs 19 now — and even lower in case of bundled individual data packs. It’s 7% of what customers paid earlier.

Prices dropped sharply after Reliance Jio, which has a 4G-only business model, launched in September 2016. However, with rising internet usage, rival companies like Airtel, Vodafone, Idea Cellular and BSNL have also expanded their 4G network.

Increasing wireless data consumption has been a boon for streaming services like YouTube, Gaana and Hotstar. Some, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, have even started commissioning and sourcing content in Hindi and other Indian languages.

Sales of “smart” or internet-ready TVs are also up. Rahul Tayal, a director at LG India, said smart TVs make up 40% of their TV sales now. Many TVs now come with apps such as Netflix, YouTube and Hotstar and consumers mirror-cast from their smartphones.

Not only data but also voice calls have increased after a dip. To keep up with Jio’s offering of free calls, competing operators have come up with their own schemes, effectively reducing voice prices to nil in case of bundled data offers.

Higher usage has not meant higher revenues and profitability for the companies. The average revenue per user (ARPU) — a key measure of a telecom company’s health — has been for GSM players from Rs 117 at the end of 2014 to around Rs 80 at the end of 2017.

The pressure is telling on older telecom players even as Jio remains aggressive and reports profits. Airtel, the country’s biggest mobile operator, has seen a decline in profitability since Jio’s launch and suffered its first loss (in Indian operations) during the January-March period this year.

2016: Rural India saw 22% jump in internet use in one year: Unicef

December 12, 2017: The Times of India

There has been a massive growth in the number of internet users in rural India registering an increase of 22% in just one year, says an Unicef study which for the first time comprehensiely looked at the different ways digital technology is affecting children’s lives across the world.

According to the report, despite children’s massive online presence – one in three internet users worldwide is a child – too little is done to protect them from the perils of the digital world and to increase their access to safe online content.

A flagship report of the Unicef released on Monday, “State of World’s Children 2017: Children in a digital world,” says internet users in rural India saw a jump of 22% between between October 2015 and October 2016 to reach an estimated 157 million. Urban internet users in the country grew by 7% during the same period to touch 263 million.

“For better and for worse, digital technology is now an irreversible fact of our lives,” said Unicef executive director, Anthony Lake, adding, “In a digital world, our dual challenge is how to mitigate the harms while maximising the benefits of the internet for every child.” The report argues that governments and the private sector have not kept up with the pace of change, exposing children to new risks and harm and leaving millions of the most disadvantaged children behind.

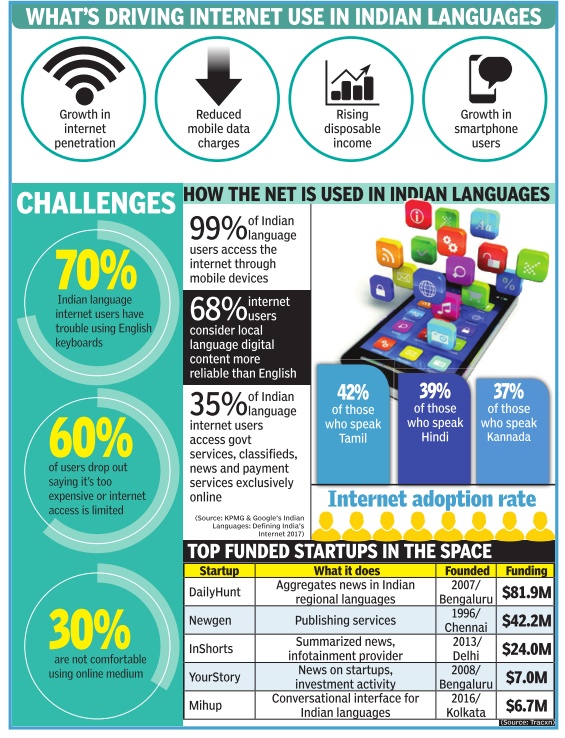

2017: Increased use

Shalina Pillai & Anand J, Cashing in on local lingo The Times of India, September 7, 2017

Lower smartphone and data costs, and technology platforms like Aadhaar and UPI are making it viable for entrepreneurs to offer more products and services to tier 2 and 3 cities, and lower income groups.

And as they do, ventures offering local language content and support are becoming important

A nuradha Agarwal first realised the potential of a smartphone when she visited her hometown Jaipur for a break in 2016, and saw the interest in learning English among many of the women members in her Marwari family .Although English didn't come naturally to many of her relatives, they all had one thing in common expensive phones. “I directed them to a few apps but they weren't comfortable with any ,“ says Agarwal. So she started a few customised chapters, which soon turned into a Facebook page with over 45,000 followers. And before long, it grew into a venture called MultiBhashi, a mobile platform that helped users learn English from 10 regional languages and vice versa. The app has seen over 95,000 downloads.

The growth of regional language users on the internet has been tremendous. A recent report by KPMG India and Google found that Indian language internet users have grown from 42 million in 2011 to 234 million in 2016, a number much higher than the 175 million English internet users in India in 2016. This spurt has helped entrepreneurs like Agarwal.

Lower data & smartphone costs

Indus OS, a mobile operating system targeted at Indians and which provides everything from the interface to app store in 12 Indian languages, works with eight Indian mobile brands including Micromax and Karbonn.Founder Rakesh Deshmukh says when they first tied up with Micromax in 2015, they were told that there would be a long term partnership only if 50,000 units were sold in a month. But in just 17 days of launch, 85,000 devices were sold. Today , Indus OS has 8 million users, and 77% of customers come from tier 2-3 cities.

Several factors have accelerated the pace in recent times lower cost of smartphones and data, the rise of Jio, and the government's focus on digital. Aadhaar, eKYC, and the UPI layers of India Stack too are helping startups, says Bala Girisaballa, Microsoft Accelerator's residence-in-chief.

“We are starting to see a lot more activity (in local languages),“ he says. The accelerator's latest batch has two AI-based startups Liv.Ai, and MegDap, which help convert local speech into text and translate one language to another.

The government's push for digital in particular its dot Bharat domain registration scheme in 2014 is what helped Ajay Data, founder of Jaipurbased Data Xgen, to come up with the idea of offering email domains in Indian languages.People can use the solution to send emails from addresses created in Indian language scripts to Gmail, Outlook, and others, as also communicate in those scripts. The company has part nered with the Rajasthan Government to provide a free email service in Hindi to all citizens.

Plenty of challenges still

Data Xgen has over 2 lakh users. But Data says he is finding it hard to scale due to challenges in integration with mainstream social media and e-commerce channels, which don't accept linguistic email address es as valid logins.

Agarwal's MultiBhashi is yet to find a viable revenue model for its consumer solution, partly because most users are from tier 2-3 cities and are unwilling to pay for the app. Agarwal, who is part of Axilor's latest accelerator batch, is trying to overcome this by targetting enterprises. She is doing pilots with a few companies to help their employees learn other languages.

The enterprise route is one that others have tried with success. Reverie Language Technologies, founded in 2009, provides language localisation for technology platforms right from the interface to the keyboard. It has 30 enterprise customers, including government bodies, internet companies and original equipment manufacturers. It has worked with the central government for its online commodities trading platform and the Karnataka government for digitising land records, says founder Arvind Pani

Investors warm up

Investors are warming up to this space, especially with the success of local language content ventures like Dailyhunt and InShorts. Virendra Gupta's Dailyhunt, an Indian language news aggregator, is the most funded in this space with $84 million. With a reach of 50 million monthly active users, Gupta says advertisements are a big opportunity. “Both financial and non-financial investors are interested in companies like ours as we are catering to the mass market,“ Gupta says.

Liv.Ai's founder Subodh Kumar agrees: “One year ago, investors didn't value regional languages much. Now they have understood the paying capacity of these regions,“ he says. His company has raised $4 million.

Asutosh Updahyay, head of programmes at Axilor, says a lot of players have emerged in the local language space. “You will have to rely on strategies that can effectively manage the app store ratings, discounts, get the right engineering, and build products which are engaging. There will be some amount of consolidation,“ he says.