Healthcare and the law: India

(Created page with "This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook

community, Indpaedia....") |

Revision as of 07:47, 26 August 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Brain death

Kerala vis-à-vis other states

Kerala has allowed doctors to withdraw life support from brain dead patients without the family’s approval. Now Maharashtra is mulling it. But questions linger about both ethics and practice

When the family of 26-yearold Priyanka Patra — admitted to a hospital in Odisha after an accident on January 26 — was told she was brain dead, they faced a dilemma. “The term brain death meant nothing to us. But we were told the condition was irreversible. In the end, we decided to donate her organs,” said Sachin Raju, Patra’s brother-in-law. The patient was certified brain dead and her kidneys were donated.

But if Patra’s family had denied permission to donate her organs, would doctors have discontinued life support? In Kerala, they could have. In the rest of India, though, things are complicated for medical practitioners.

How India defines brain death

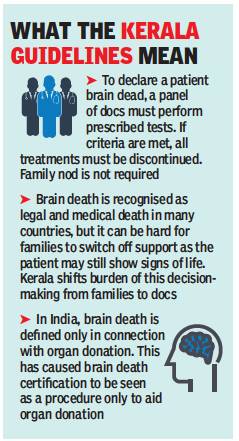

In India, brain death has been defined only in connection with organ donation under the Transplantation of Human Organs (THO) Act, 1994, which has led to the certification being viewed mostly as a procedure only to aid organ donation. But what if a family says it doesn’t want to donate organs? There is little clarity on what happens then. In most cases doctors refuse to switch off the ventilator and support systems fearing legal implications.

But the medical fraternity does agree that once a diagnosis of brain death has been made, treatment should not continue as it would be a “futile intervention”. The family may hold false hopes for the patient’s recovery while ICU facilities, limited in India, would continue to be engaged. New guidelines Kerala issued last month aim to address this by shifting the onus of decision-making from families to doctors who can discontinue life support without family approval. It has also laid out a 10-step procedure for certification.

“If a person is declared brain dead, it means they are dead. But it is challenging for doctors and the patient’s family to decide whether to continue life support,” Dr Banambar Ray, senior critical care specialist at a hospital in Odisha, told TOI.

How brain death is diagnosed

In most states, only when a family agrees to donate organs of a patient declared brain dead, the steps for certification, as laid out under the THO Rules (1995), kick in. The rules state that a team of four medical experts can diagnose brain-stem death (brain stem is part of the brain that regulates essential functions like breathing, heartbeat and blood pressure). To certify brain-stem death, a patient should be deeply comatose, on ventilator because of lack of spontaneous respiration and all brain-stem reflexes should be absent. All prescribed tests have to be repeated, after an interval of six hours.

“The assessment is undertaken only after social workers in the hospital report willingness of a patient’s family to donate organs. If the family backs out after the committee’s assessment, a patient’s treatment continues,” said S N Shankhwar, chief medical superintendent, King George’s Medical University in Lucknow.

Dr Rajesh Shetty, chief of clinical services at a hospital in Karnataka, added, “The gap between brain death and cardiac death may be days. This is a burden for the patient’s family that faces an ethical dilemma — whether or not to discontinue life support. As per law, even in hospitals licenced for organ transplant, brain death is not sufficient to withdraw treatment if the family does not opt for organ donation.”

There are no guidelines on what standard of care should be followed when the family does not want to donate organs. But in Kerala, the process of brain death declaration has been delinked from organ donation. This came after the state constituted an expert committee to develop parameters for brain death certification “to remove the ambiguities in the minds of health care providers as well as the public.”

Writing in a September 2018 edition of the peer-reviewed Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, authors Sunil Shroff and Sumana Navin had argued, “Delinking brain death from organ donation is essential and this requires inclusion of ‘brain death’ in the definition of death in the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, (RBDA) 1969, so that a uniform policy can be framed.”

Dead or alive?

The RBDA defines death as “the permanent disappearance of all evidence of life at any time after livebirth has taken place” while the THO Act defines death as a “permanent disappearance of all evidence of life, by reason of brain-stem death or in a cardio-pulmonary sense at any time after live birth has taken place”.

Since a brain dead person can still exhibit signs of life — such as breathing with ventilator support — it can be argued they are still alive as RBDA Act does not mention brain-stem death. Medical practitioners have long asked for inclusion of “brain death” on the death certificate but there is no provision for it and death in such cases is mentioned as cardiopulmonary death.

In Maharashtra, doctors are seeking Kerala-like clarity. Dr Astrid Lobo Gajiwala, director of the Western Region cum Maharashtra State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation, has sought that critical care experts review the Kerala order. The committee’s recommendations will be forwarded to the Maharashtra directorate of health services. “A directive would be useful as doctors are not sure how to interpret the law, since brain-stem death is defined only in a law that links it with organ donation,” said Gajiwala.

Doctors’ dilemma

With absence of well-defined protocol for brain death cases, doctors often find themselves on tricky terrain.

Dr Rajendra Kumar S, an intensivist in Karnataka, said that lack of guidelines makes it difficult for doctors to withdraw life support. “Family can sue the doctor saying that if treatment were continued, the patient may have survived.” Dr Sadiq Sikora, director of gastrointestinal surgery in a Karnataka hospital, added, “By keeping a brain-dead person on ventilator, we burden the family with the decision making. What also has to be seen is our country’s resource crunch with very few ventilator beds available in ICUs.”

In Tamil Nadu, doctors said there was enough clarity that brain death meant death. Sunil Shroff on the advisory committee of the state transplant authority, Transtan, said, “After brain death …ventilators can be turned off.”

But not all agree that removing family from the equation is right. Dr Saroj Patnaik from the Odisha hospital that declared Patra brain dead, said doctors withdrawing life support without kin’s nod would be akin to them playing God. “Instead, we should have a robust counselling system in hospitals for families of brain dead patients to help them make a decision.”