Rogan art

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | [[Category:Handicrafts |R ]] | + | [[Category:Handicrafts & Handlooms |R ]] |

=Khatris, the custodians= | =Khatris, the custodians= | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

“As a designer you want to present something out-of-the-box to your clients and such crafts give you exactly that. Clients also value handmade traditions.” | “As a designer you want to present something out-of-the-box to your clients and such crafts give you exactly that. Clients also value handmade traditions.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:India|R | ||

| + | ROGAN ART]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|ROGAN ART]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:10, 13 October 2022

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

[edit] Khatris, the custodians

[edit] A

The Khatris are the surviving custodians of the art form. During the first phase of lockdown, the Khatris collaborated with India Craft Week, Delhi and Paramparik Karigaar Mumbai showcasing their collection in online exhibitions.

Jabbar Arab Khatri, nephew of Padma Shri awardee Abdul Gafoor Khatri, and one of the young torchbearers of the art says, “The dyes take time to dry during the monsoon, so we are indoors working with designs.” He is happy with the online initiative. “Although there were no sales, we had many enquiries for our products and workshops; some of them have promised to get back once normalcy returns,” he says.

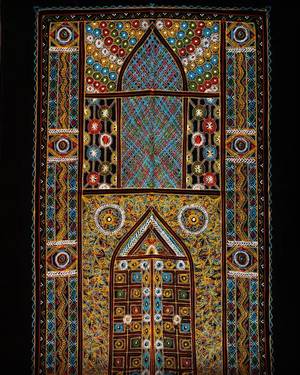

A word of Persian origin, Rogan means oil. Jabbar explains the cloth printing process: “Castor oil is heated and cast into cold water and the thick residue is then mixed with natural colours. Then, using a stylus or blocks, this resultant paint is meticulously transferred on to a cloth to make floral, animal (peacock) and geometric patterns. The weather and density of the mix play an important role. Colours and freehand motifs look attractive.”

In the last few weeks, Jabbar has made a few Rogan art wall pieces on the masks for COVID-19. One of the sketches was given by Mubarka Nandarbarwala, an National Institute of Fashion and Interior Designing, Mumbai (NIIFD) student after his Instagram session. He shares, “Since students couldn’t come here for workshops, it was a nice opportunity to present our historic art to them,” NIIFD teacher Rosie Bose calls it an effort to introduce different art practices to the students. “Executing Rogan art by learning online is tough but once they are exposed to the crafts component, maybe later, we can take these students to Nirona for a workshop. Since they have already been introduced to the art, learning directly from these artisans will be a fascinating experience. Budding fashion designers could bring fresh ideas and help in sustaining the art and make it relevant in the fashion industry.”

[edit] B

Neeraja Murthy, October 16, 2019: The Hindu

From: Neeraja Murthy, October 16, 2019: The Hindu

In a casual tee and trousers, rogan artist M Jabbar Arab Khatri has just finished taking a walk around Punjagutta exploring the city. It has been only two days since his first visit to Hyderabad but we realise the city is not a stranger to him. He shows the photograph of a rogan art done on a fabric where the city’s splendid architecture had come alive. Resplendent with earthy colours, elaborate motifs and intricate detailing, Hyderabad’s edifice stands tall here. Royalty and heritage is a common factor that binds Hyderabad and rogan art of Kutch with a 300-year-old history. With floral, animal (peacock, elephant) geometric designs, this ancient art of hand-painting is a treasure of Kutch. There is no particular theme as the artisans paint what they feel.

Organised by city-based Studio Amoli, the two rogan art workshops conducted at Phoenix Arena and ACK Alive brought Jabbar to the city. Hailing from Nirona village of Kutch in Gujarat, the Khatris are traditional artisans. Among the few families that practised this time-consuming and painstakingly difficult rogan art, Khatris are the only ones left still continuing this art form. “The turning point came in 1985,” says Jabbar sharing how his uncle Abdul Ghafur Khatri left the family tradition and went to Bombay. “My grandfather wrote a letter asking him to come back. He returned and has been instrumental in retaining its old glory,” he says. It was a moment of pride when Ghafur won a Padma Shri recently. The Khatris are a big joint family consisting of three families; With 10 members working in the rogan art unit, Jabbar’s father, Arab Hasam Khatri is also a national award winner and the family members have won around 18 state and national awards among themselves.

Jabbar studied only till X std in Gujarati medium and often played cricket with his friends on open grounds. “We never force young members in the family to take up this art; They get attached with their own interest,” he says giving his own example. He found his calling in rogan after discontinuing studies but his first exhibition at Crafts Museum in Delhi along with his father was not as expected. “I stayed on when I realised I enjoyed the art despite challenges,” he says.

One of his endeavours has been to popularise and blend the art to suit contemporary needs. Traditionally, rogan art was done on skirts and quilt covers. “Our work is handmade, intricate and hence expensive. There was a lot of struggle when cheap prints hit the market. Our family members worked even as labourers to sustain the art. It is only now that we have got the platform,” he says.

The art finds a place in utility products including mobile covers, sling and shopping bags. The tree of life design (copyright by Ghafur) is a popular wall piece. Jabbar informs Prime Minister Narendra Modi had gifted this Tree of Life to former US President Barack Obama when he had visited the U.S. in 2014.

Gafur also made news when he created a sari with rogan art (it takes six months to make one). Two years ago, the art found a digital market place too. “One needs a lot of patience. Care has to be taken to see that the stroke remains the same,” he adds. Jabbar has been touring India. Deepavali and the next two months after the festival is a busy period when tourists flock their village. “During winter season, around 400 people visit our house. Many legendary actresses like Waheeda Rahman and Asha Parekh had visited us.”

The Kutch Rann Utsav has also helped bring many tourists. “As the days are short in winter and gets difficult to dry the fabrics, we do not focus much on the work. During monsoon, we focus on intricate designs that can be done indoors. We also have to take care that the fabric doesn’t move because of wind,” he shares.

Their village is also a hub for many young researchers and fashion students wanting to document their lives and create fabrics with their art. “We are also famous as they show rogan history on National Geographic,” he smiles. Jabbar hopes designers draw inspiration from rogan and the art form finds a place in fashion weeks.

“We are working with leather to create bags and wallets; the sad part is some replicate our base colours to create duplicate products,” bemoans Jabbar.

[edit] C

Anjali Jha, July 8, 2020: The Indian Express

Rogan, a 300-year-old craft tradition that once flourished in Gujarat’s Kutch region. In 1983, a young Abdul Gafur Khatri followed the trend and went to Ahmedabad and even Mumbai to find work and make a life. He says, “At that time, there were no tourists visiting Gujarat and our art was not selling. It was only later that the government gave us a project that started helping us and my grandfather and father asked me to return to the village.”

Gafur became so attached to Rogan that he promised his father to take it to the international level, which he did eventually. “I fulfilled my promise when Rogan art was presented to Barack Obama, the then President of the United States, by Narendra Modi during his visit to the US in 2014,” says Abdul Gafur Khatri, the recipient of Padma Shri Award (2019), five National Awards, eight State awards, three National Merit certificates and an International Designer award.

“We have been practicing Rogan for 46 years. If we don’t do this, no one else will, and the art will be lost forever. I never dreamt of doing anything else. It is our responsibility to take our age-old tradition forward, make changes and improve the designs as much as we can,” adds Khatri. He is now teaching Rogan to all the women willing to learn in his village in collaboration with a non-profit organisation to keep the art alive.

Khatri believes it’s the colours and freehand motifs that make it most appealing. “All the Rogan crafts are made without khaka (which means layout or blueprint). It’s basically a huge canvas and a metal rod with colourful paint.” Rogan, he informs, is the technique of painting on fabric, using a thick brightly coloured paint-like substance made with castor seed oil. Artisans place a small amount of the paste into their palm, and the paint is carefully moulded into patterns using a metal rod at room temperature. The rod, which acts as a paintbrush, never comes in contact with the fabric. Later, artisans fold the fabric, creating a mirror image and with it, a design symmetry, he explains.

Designer Vanshika Gupta, who runs her eponymous label and visited Kutch for a week, says: “I visited Abdul Gafur Khatri Bhai to learn the craft. During the documentation, I realised that the crafting process, the paint they make, the techniques and chemicals they add to the colour to make it sticky, is only known by this family and no one else. You can see so many examples in their home. They are very generous people and humble, they patiently teach you to work on it.”

She adds, “The amazing part is that when you complete your design and press it upon a plain cloth, folding for about five minutes, you will find that both fabrics have the same design. Rogan is a mirror art; the paint is sticky and transfers to the other cloth.”

On how the art can become a part of fashion, Gupta explains, “There are many ways in which we can incorporate the Rogan craft in our collection. For eg, a black skirt with multi-colour bold Rogan lines as polygons, along with a floral ‘jaal’ in metallic foil or a holographic design.” But she warns, “Despite so many cultural nuances, the craft is slowly dying. It has yet to appeal to a contemporary audience.”

What are the problems faced by craftspersons

Much of the craft depends on two factors — temperature and weather. If it is the rainy season, the dyes take time to dry and it becomes difficult to transfer onto the fabric. In winter or summer, the design may dry before it can be shifted to another fabric. Another issue is getting the density of the paste as this can affect the entire design.

Moreover, as the pandemic unfolded, it has destroyed their peak season, which includes the tourist season from January to April and again from July to September. The craft workshops and tourism to Nirona village had to be cancelled. The raw materials, which had been sourced for this crucial period, are also lying unused.

Designer Gautam Gupta who loves Rogan feels the craft has evolved, though it needs more support in terms of motifs and colours. “The Rogan craft is one of the most unique hand-painted styles in India. It also has a different effect when paired with other textures. The intricacy and colour make it perfect for value additions. Seeing the changes in preferences of millennials and the global audience, artists too realise the need to be innovative. Anyone using Rogan painting in their design process will make their own motifs, colour combinations and textures,” he says.

“As a designer you want to present something out-of-the-box to your clients and such crafts give you exactly that. Clients also value handmade traditions.”