Indian cinema: viewership outside India

(Created page with "{| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.<br/> Additional information ma...") |

Latest revision as of 16:59, 3 February 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

[edit] Egypt

[edit] 1950s- 2010s

Avijit Ghosh, January 24, 2023: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh, January 24, 2023: The Times of India

Over the next few days, India-Egypt bonhomie will be further burnished by a series of bilateral agreements and the diplomatic affability will also reflect in President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s presence as the chief guest at the Republic Day celebrations.

But the cultural ties run deeper. Over a swathe of decades in the land of Mo Salah, many Egyptians have built a personal bond with Hindi films. They have thronged to watch Dilip Kumar’s Aan, gorged on Big B’s Mard on grainy VHS tapes and queued up for Shah Rukh Khan’s My Name is Khan in Cairo.

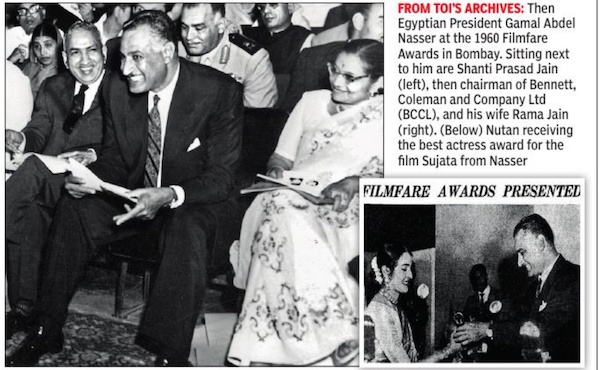

It isn’t just the people, even presidents have loved Hindi cinema. Not many know that Egypt’s (then) President Gamal Abdel Nasser attended the 7th Filmfare Awards in Bombay in 1960.

The attraction is mutual. Bollywood too has been fascinated by Egypt’s landscape and monuments, especially the pyramids. From Bachchan in The Great Gambler (1976) to Akshay Kumar in Singh is Kinng (2008) – Hindi cinema’s biggest and brawniest have bashed up baddies and shimmied to songs there.

Ancient as the two civilizations are, shared anti-colonial objectives have crafted modern associations between Egypt and India. The Union ministry of external affairs said in 2014 that Mahatma Gandhi and Egyptian statesman Saad Zaghloul had common goals on independence of their countries. The ties were elevated by the close friendship between Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru, leading to a Friendship Treaty between the two nations in 1955. Nasser and Nehru, along with Yugoslavia’s Josif Broz Tito, were regarded as the three pillars of the global Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

But beyond the world of politics and diplomacy, an invisible people-to-people connection was forged beginning in the 1930s through the world of moving pictures in darkened theatres.

In an insightful paper titled, The Ubiquitous Nonpresence of India, Oxford professor Walter Armbrust referred to the fan magazine Al Kawakib (The Star) to show how Hindi cinema had come to be discussed in Egypt, though not always positively, in the 1930s.

But the cultural kinship side of the cinematic association wasn’t ignored either as a 1957 article in the samemagazine showed. “The secret to the success of Indian films in Egypt is that they portray a common life of both the Indian and the Egyptian, with only trivial differences attributable to environmental factors. The music in these films moves us and lifts our spirits because it springs from the same source: the magic of the East and its spirituality. ” Egypt boasts a film industry of its own and the 1940s to 1960s period is regarded as “the Golden Age of Egyptian cinema”.

Trade Guide, a Hindi film business magazine, acknowledged in 1963 that Egypt produces technically high-standard films while also importing movies from the US and UK. “The audience is sophisticated and only first-class films with powerful story and colour element will be a commercial success,” said an article headlined, World Market for Indian Films.

The 1980s marked the arrival of video cassettes, which turned cinema-viewing into home entertainment for the first time. Pirated VHS tapes further expanded the global reach of Bollywood films and stars. From the1980s onwards, Bachchan became a megastar in Egypt.

“Bachchan skyrocketed into Egypt’s cinema star constellation with films like Geraftaar and Mard (1985) that viewers saw in theatres or watched on video cassette. . . Back in India, Bachchan’s films from the late 1980s did not attract audiences like they had at the peak of his stardom, when he was known as the ‘Angry Young Man’. But the later films still had enthusiastic fans in Egypt,” wrote Texasbased academic Claire Cooley in film journal Jump Cut.

Armbrust recalled two fascinating anecdotes that illustrate the extent of Big B’s popularity in Egypt. He wrote, “One urban legend circulating in the early 1990s was that a plane carrying Amitabh Bachchan touched down briefly in the Cairo airport for refuelling. Word got out about the Hindi star’s presence, and tens of thousands of people came to the airport hoping to catch a glimpse of him. I saw a more concrete example of Bachchan’s presence in the displays of vendors in a popular market near downtown. Some of these vendors sold tee shirts emblazoned with the face of Bachchan. ”

It’s a point that Ahmad Mohd Ahmad Abdel Rahman, head, department of Urdu, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, reaffirmed in 2011. “If any Indian is spotted on the streets, the first welcoming words people utter are ‘Hello, Amitabh Bachchan,” he had told TOI then. It’s a matter of academic exploration how an individual becomes synonymous with a nation.

Egypt’s love affair with Hindi cinema has continued in recent years. In 2015, journalist Ati Metwaly wrote on Ahram Online how the Egyptians flocked to a Bollywood dance workshop at the Indiaby the Nile festival. “Young Egyptians hum Indian songs even if they don’t understand the lyrics,” Metwaly said.

Shah Rukh Khan is wildly popular in Egypt. King Khan’s immense draw is exemplified by a 2021 incident that Ashwini Deshpande, who teaches at Ashoka University, divulged on social media. She tweeted, “Needed to transfer money to a travel agent in Egypt. Was having problems with the transfer. He said: you are from the country of @iamsrk. I trust you. I will make the booking, you pay me later. For anywhere else, I wouldn’t do this. But anything for @iamsrk…” Later Shah Rukh heartwarmingly sent his autographed photos and a handwritten note to the travel agent.

The occurrence underlines the power of cinema: how it can demolish geographical distances and cultural differences and touch the heart, how it can shape attitudes towards an entire people and a country. Hopefully, there are more stanzas to be sung in this enduring duet.