World War I and India

(→Martyrs) |

(→See also) |

||

| Line 394: | Line 394: | ||

[[World War I and India]] | [[World War I and India]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[World War 1: The Dogras]] | ||

[[World War II and India]] | [[World War II and India]] | ||

and many more... | and many more... | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Defence|WWORLD WAR I AND INDIA | ||

| + | WORLD WAR I AND INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:History|WWORLD WAR I AND INDIA | ||

| + | WORLD WAR I AND INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|WWORLD WAR I AND INDIA | ||

| + | WORLD WAR I AND INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|WORLD WAR I AND INDIA | ||

| + | WORLD WAR I AND INDIA]] | ||

Revision as of 11:32, 30 June 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

Contents |

India & The Great War

The First World War, or The Great War, as it was then known as, was reported extensively by the then British owned Times of India, with stark details of battles and other events. In particular, the valour of thousands of Indian troops fighting for the British found mention a number of times.

A TOI report dated June 4, 1915 said, “A few weeks ago some papers of the baser sort were hinting at what they were pleased to call the failure of the Indian troops at the front. The object of this was never clear, but it is obvious that the reports must have given enormous pleasure to the Germans who are always glad of an excuse to express their contempt and resentment at the employment of Indian troops against them. The nation which uses poisonous gases and which poisons wells can of course afford to be particular about such matters as the colour of the soldiers whom it fights. But whatever lies and base suggestions may have been circulated, the Germans long ago found out the quality of the men sent to fight them, and in today’s list of the recipients of the Order of British India and the Indian Order of Merit will be found a number of cases recorded in which Indians have shown the greatest gallantry under fire.”

The Theatres of Operation

Brighton, India soldiers in

The Times of India, Oct 14 2015

A British resort to unveil WWI letters written by Indian soldiers

A seaside resort town in Britain has never seen before letters sent home by Indian soldiers expressing their personal thoughts on fighting for Britain in World War I. Brighton has sound recordings of Indian soldiers in German prisoner of war camps and also tell the world stories of extraordinary Indian individuals such as Sophia Duleep Singh, an Indian maharajah's daughter, suffragette and nurse. The Pavilion between December 1914 and January 1916 was solely used as a hospital to treat wounded Indian soldiers. The Pavilion, Dome and Corn Exchange housed a total of 724 beds. By 1916, over 4,000 Indians and Gurkhas had been treated there. During WWI (1914-18) over one and a half million Indian army soldiers saw active service alongside British troops.Twelve thousand Indian soldiers who were wounded on the Western Front were hospitalised at sites around Brighton.These included York Place School, the Dome, the Corn Exchange and the Royal Pavilion.

France: Indian soldiers in

Shashi Tharoor, December 09 2014

Little is known of Indian soldiers who fought World War I, in the war's centenary.

Exactly 100 years after the “guns of August” boomed across the European continent, the world has been extensively commemorating that seminal event. The Great War, as it was called then, was described at the time as “the war to end all wars“. But while the war took the flower of Europe's youth to their premature graves, snuffing out the lives of a generation of talented poets, artists, cricketers and others whose genius bled into the trenches, it also involved soldiers from faraway lands that had little to do with Europe's bitter traditional hatreds. Of the 1.3 million Indian troops who served in the conflict, however, you hear very little.

The most painful experiences were those of soldiers fighting in the trenches of Europe. Letters sent by Indian soldiers in France and Belgium to their family members in their villages back home speak an evocative language of cultural dislocation and tragedy. “The shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon,“ declared one. “The corpses cover the country like sheaves of harvested corn,“ wrote another.

The British raised men and money from India, as well as large supplies of food, cash and ammunition, collected both by British taxation of Indians and from the nominally autonomous princely states. In return, the British had insincerely promised to deliver progressive self-rule to India at the end of the war.

Mahatma Gandhi, who returned to his homeland for good from South Africa in January 1915, supported the war, as he had supported the British in the Boer War. The great Nobel prize-winning poet, Rabindranath Tagore, was somewhat more sardonic about nationalism: “We, the famished, ragged ragamuffins of the East are to win freedom for all humanity!“ he wrote during the war. “We have no word for `Nation' in our language.“

India's absence from the commemo rations, and its failure to honour the dead, were not a major surprise: the general feeling was that India was ashamed of its soldiers' participation in a colonial war and saw nothing to celebrate.

But the centenary is finally forcing a rethink. Remarkable photographs have been unearthed of Indian soldiers in Europe and the Middle East, and these are enjoying a new lease of life online.Looking at them, i find it impossible not to be moved: these young men, visibly so alien to their surroundings, some about to head off for battle, others nursing terrible wounds.

My favourite picture is of a bearded and turbaned Indian soldier on horseback in Mesopotamia in 1918, leaning over in his saddle to give his rations to a starving local peasant girl. This spirit of compassion has been repeatedly expressed by Indian peacekeeping units in UN operations since, from helping Lebanese civilians in the Indian battalion's field hospital to treating the camels of Somali nomads. It embodies the ethos the Indian solider brings to soldiering, whether at home or abroad.

For many Indians, curiosity has overcome the fading colonial-era resentments of British exploitation. We are beginning to see the soldiers of World War I as human beings, who took the spirit of their country to battlefields abroad. The Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research in Delhi is painstakingly working to retrieve memorabilia of that era and reconstruct the forgotten story of the 1.3 million Indian soldiers who had served in World War I. Some of the letters are unbearably poignant, especially those urging relatives back home not to commit the folly of enlisting in this futile cause. Others hint at delights officialdom frowned upon; some Indian soldiers' appreciative comments about the receptivity of Frenchwomen to their attentions, for instance.

Astonishingly , almost no fiction has emerged from or about the perspective of the Indian troops. But Indian literature touched the war experience in one tragic tale. When the great British poet Wilfred Owen (author of the greatest anti-war poem in the English language, `Dulce et Decorum est') was to return to the front to give his life in the futile World War I, he recited Tagore's `Parting Words' to his mother as his last goodbye. When he was so tragically and pointlessly killed, Owen's mother found Tagore's poem copied out in her son's hand in his diary .

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains war cemeteries in India, mostly commemorating World War II. The most famous epitaph of them all is inscribed at the Kohima war cemetery in northeast India. It reads, “When you go home, tell them of us and say For your tomorrow, we gave our today .“

The Indian soldiers who died in World War I could make no such claim.They gave their “todays“ for someone else's “yesterdays“. They left behind orphans, but history has orphaned them as well. As Imperialism has bitten the dust, it is recalled increasingly for its repression and racism, and its soldiers, when not reviled, are largely regarded as having served an unworthy cause.

But they were men who did their duty, as they saw it. And they were Indians. It is a matter of quiet satisfaction that their overdue rehabilitation has now begun.

Laventie and 39th Garhwal Rifles

Victoria Cross winner Negi among 721 dead, Oct 27 2017: The Times of India

From: Victoria Cross winner Negi among 721 dead, Oct 27 2017: The Times of India

They fought a war that was not theirs and died anonymously on foreign shores. Now, over a century after they enlisted in the British Indian Army and were sent to France to fight in World War I, the remains of two soldiers of the 39th Garhwal Rifles regiment, found in a field in northwestern France, will finally be brought home.

The two men were found along with the bodies of a British and a German soldier, buried in a field near the town of Laventie, nearly 70 km from Dunkirk.

“The discovery was made during digging for civic work in a field in September 2016.Among the remains were the insignia of 39 Garhwal Rifles.French officials confirmed the finds and wrote to us. Now a team of four Indian defence personnel, including a Garhwal Rifles brigadier, will visit the site next month. Some artefacts, including the regimental insignia, have also been found. Our team will try to determine the identities of the soldiers, and see if any other details can be found,“ said a Garhwal Rifles officer posted in Lansdowne. We will try our best to identify them, although it will be dif ficult. The bodies were buried for more than 100 years, so very little is left,“ the officer said.

Men of the Garhwal Rifles fought in various fronts in the World War I as well as in the World War II. In the first conflict, 721 men from the regiment were killed, while 349 died in World War II.

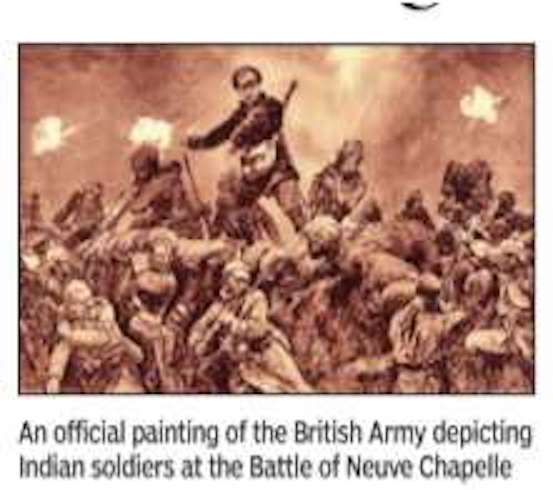

Among the most famous of them was Gabar Singh Negi, who won the Victoria Cross for his actions at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in France, where he died on March 10, 1915.

The site of the battle is less than 8km from Laventie, where the bodies of the two soldiers were found, which could also indicate that they were killed during the battle.

After Neuve Chapelle, 39th Garhwal Rifles was posted to Mesopotamia (now Iraq). More than 1 million Indian men served in World War I, of which more than 62,000 were killed.Hundreds of them were buried in graves maintained by the Imperial War Graves Commission in countries like France and Belgium.

There is a Neuve-Chapelle Indian Memorial to the war dead to commemorate Indian troops' involvement in that battle.

After World War I, 39th Garhwal Rifles was renamed 39th Royal Garhwal Rifles, and later re-numbered as 18th Royal Garhwal Rifles. The regiment is now known as Garhwal Rifles, with the `royal' dropped in 1950.This sequence of events, said serving officers, indicates that the men found at Laventie had died during World War I.

German praise

Even the Germans had a word of praise for India’s soldiers. A December 5, 1914 report in TOI said: “The Frankfurter Zeitung publishes a letter from a German soldier showing that the Germans are beginning to realize the fighting qualities of the Indians. He says: — “We at first spoke with contempt of the Indians, but today we have learned to regard them in a different light, and they will certainly not be underrated. We lay for three days under shellfire, lacking the barest necessities, and then had a visit from the Indians”.

“The Devil knows what the English have put into those fellows. They stormed our lines as though they possessed an evil spirit, with fearful shouts, compared to which our hurrahs are like the whining of a baby. Thousands rushed at us suddenly as if they had been shot out of the fog.”

“We opened a destructive fire, mowing down hundreds, but others advanced, springing like cats and surmounting obstacles with marvelous agility. They entered our trenches in no time and fought with butt-ends, bayonets, swords and daggers. We had bitter hard work till reinforcements arrived.”

Another article describes Indian troops arriving in France as “a fascinating and mysterious invasion from the Arabian Nights”. The French writer even imagines “Gurkhas creeping at night through the mud towards the enemy’s patrols like tigers”.

Gallipoli 1915

The battle

At daybreak on August 9, 1915, a young lieutenant of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, British Army, watched in awe as an Indian Army battalion almost ended the stalemate at Gallipoli. Men of the 1/6 Gurkha Rifles rose from their positions and pressed up the Sari Bair ridge, crested the heights between Chunuk Bair and Hill Q, and drove back the Turks after some desperate hand-to-hand fighting. The Gurkhas looked down at the waters of Hellespont—the original objective of the Gallipoli campaign. No Allied unit would repeat the feat ever again.

With no backup coming, the Gurkha commander, Major C G L Allanson, decided to go after the fleeing Turks. But they had hardly moved 200 yards when a murderous artillery barrage broke up the attack. According to Major Allanson, it was the Royal Navy that had shelled them, mistaking them to be Turks. The Gurkhas had to withdraw, but they did so in good order.

The action that day left a lasting impression on that British officer who resolved to get a transfer to the Indian Army. Four years later, his wish came true when he got placed in the same regiment that had impressed him at Gallipoli. He was Field Marshal Viscount William "Bill" Slim whose Fourteenth Army destroyed the Japanese juggernaut in the Second World War.

The Gallipoli campaign was a complete disaster for the allies as much as it was a crowning glory for the Turks who doggedly defended their country. Though Turkey eventually lost the war, Gallipoli became the most defining moment in its history.

On the Allies' side, it were the Australians and New Zealanders who found their national identities on Turkish soil. The term Anzac almost immediately assumed a politico-cultural identity, though militarily Anzacs may not have had the kind of impact that the world thinks today they did.

Nevertheless, Gallipoli is the Mecca of Aussies and Kiwis today. Thousands of them go there every year on Anzac Day. And Turkey, right from Mustafa Kemal's time, has allowed them right of passage. In fact, this war pilgrimage started after Ataturk made that famous speech in 1934 where he said: "Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives... you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets where they lie side by side here in this country of ours... You the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. Having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well".

Kemal, with his amazing foresight, ended the bitterness among Turks and Australians/New Zealanders. Yet the same sagacity wasn't shown by leaders of Independent India.

In fact, India, after independence, followed a different policy towards the world wars—that of selective amnesia. As a result, the Indians today have distinguished themselves by not knowing anything about the role played by our troops in Gallipoli or anywhere else. The Indian tourist reacts with disbelief when a Turkish guide shows him Indian graves at the war cemeteries in the peninsula or talks about Indian valour. "Wow! Really? Strange," exclaims the Indian, visibly embarrassed, when his Turkish guide catches him by surprise. With this kind of ignorance, it's only natural that most Indians of today cannot understand the reasons why Indians fought, the conditions they fought in, and the politics that was played on them.

In Gallipoli, the Allied commander-in-chief, General Sir Ian Hamilton, wanted a Gurkha brigade. Hamilton was an old India hand and knew what the Gurkhas were capable of. In the hilly terrain of Gallipoli, Gurkhas could be his trump card, he thought. But what he got was the 29th Indian Infantry brigade with just one Gurkha battalion (1/6 Gurkhas). The other three were the 14th Ferozepur Sikhs, 69th Punjabis and 89th Punjabis—the latter two were predominantly Muslim.

There is no reason to believe that the Muslim soldiers fought any less bravely than others, but the 69th and 89th Punjabis were withdrawn after a while on the grounds that they were Muslims and could have qualms about fighting Muslim troops of the Ottoman Sultan. This was after they had sustained heavy casualties in the campaign. The British, it is said, didn't want a repeat of the Singapore Mutiny of January 1915, and they were acutely aware of Ghadar Party's efforts to foment rebellion among Indian troops stationed abroad.

But it was never explained why the Muslim troops of the 7th Indian Mountain Artillery Brigade were never withdrawn. In hindsight, it seems it was a facade created by Hamilton to get in his favourite Gurkha troops, for the two battalions were replaced by the 1/5 and 2/10 Gurkhas.

The Ferozepur Sikhs, on the other hand, fought true to their reputation. In the Battle of Krithia, they led frenzied charges on Turkish trenches. A Times of India report of 1915 detailed how the Sikhs, despite facing heavy losses in face of heavy machinegun and rifle fire, led a bayonet charge on the Turkish trenches facing them and killed the defenders. But this bravery cost them dear: the battalion lost 82% of its strength and had to be attached to a Gurkha battalion until they were reinforced by Patiala state troops. But the latter troops, also Jat Sikhs like the Ferozepur battalion, never got any recognition. In fact, history goes silent on their role in Gallipoli (Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala was apprehensive of his troops being attached to the Ferozepur battalion, fearing the 14th Sikhs would overshadow his men. And that's how it happened).

No less than 15,000 Indians took the field at Gallipoli and 7,000 went into the casualty list. We suffered as badly as the rest; but while others haven't forgotten what their troops did, we have never bothered to find out how ours fought and died.

India sent the largest army (13 lakh) to the war

In key battles at Gallipoli than previously estimated, says Australian historian

The Gallipoli campaign of the First World War in 1915 was a disaster for the Allies. Yet it was the defining moment in the history of Australia, New Zealand and Turkey--their national identities were forged on Turkish soil. India, though a major player, was given a short shrift and the number of troops in the Indian Expeditionary Force G at Gallipoli was pegged at only 5,000 for a century .That narrative is about to change. Australian military historian Professor Peter Stanley has said in his latest book, Die in Battle, Do Not Despair, that there were actually 16,000 Indians at Gallipoli, and 1,600 perished fighting the Mehmets. Stanley found evidence to this effect at the National Archives of India in Delhi last year, but it was difficult to dig out individual stories as Indian troops, the vast number of them being illiterate, left no written accounts of the war. In the absence of memoirs, the Indian soldier of the First World War has remained a nameless, faceless entity and his contribution was reduced to a footnote in the pages of history -a paradox since India sent the largest army of volunteers (1.3 million) to the war.

“I accessed all possible records available in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, Turkey, Nepal and India, and managed to piece together the individual stories of 200 Indians at Gallipoli. I can put my hand over my heart and say that the Indian role was all positive,“ Stanley told Sunday Times.

Indians and the Anzacs (Australia and New Zealand Army Corps) first met up in Egypt in 1914 before the Gallipoli campaign started. At dawn on April 25, 1915, the Anzacs landed on the beaches of Gallipoli under the cover of fire provided by troops of the 7th Indian Mountain Artillery Brigade.“The Indian mountain artillery was the only artillery available at that time and the Anzacs remembered this help,“ Stanley said. Soon after, the 29th Indian In fantry Brigade composed of the 14th King George's Own Ferozepore Sikhs (4 Mech today), 16 Gurkha Rifles (now Royal Gurkha Rifles), 69th Punjabis (1 Guards) and 89th Punjabis (1 Baloch, Pakistan Army), joined battle. But, colonial politics came into play.

“The Punjabi battalions were Muslims. They were withdrawn on the ground that being Muslims, they may have qualms about fighting the troops of the Caliph. The real reason was the theatre commander, General Sir Ian Hamilton, wanted a Gurkha brigade. The hilly terrain of Gallipoli was most suitable for the Gurkhas as they were trained in mountain warfare, he thought. So the Punjabis, despite fighting valiantly and gloriously, were unfairly withdrawn and replaced by the 15 and the 210 Gurkhas. Yet the 7th Indian Mountain Artillery Brigade was never withdrawn although 75% of its troops were Muslims,“ Stanley said. Un fortunately, even today, ill-in formed commentators on socia media use this instance to ques tion the loyalty of Muslims in the Indian Army .

The Gurkhas, true to their The Gurkhas, true to their reputation, captured a hilly feature in May -called the Gurkha Bluff in their honour -and in August, they crested the Sari Bair ridge and came closest to ending the stalemate at Gallipoli. They had to withdraw when the Royal Navy shelled them thinking they were Turks. “We could speculate that had the Indian troops been used earlier in the campaign, Gallipoli may have had a different outcome,“ Stanley said.

The fighting qualities and discipline of the Indians had a profound impact on the Anzacs.“The British were apprehensive about clubbing Indians and Anzacs together as they thought the Anzacs would ill-treat them, but Indians and Anzacs developed a unique camaraderie. Indians were admired because they were professional and skilled soldiers unlike the Anzacs who were just volunteers,“ he said.“Many Australians officers commented in their diaries that Indians were role models.“

The Suez Canal

The report goes on to describe an incident where Indian troops showed exemplary courage under fire.

“Havildar (now Jemadar) Suba Singh, 56th Punjabi Rifles Frontier Force, in command of a patrol o f nine men on the Suez Canal, surprised and engaged a strong raiding party of Turks estimated at 400 under German officers, and in the fight that ensued he showed a determined front and fought with great gallantry. Although severely wounded, Havildar Suba Singh continued to lead and encourage his men and extricated his patrol from a very difficult situation with a loss of two killed and three wounded, whilst the losses to the enemy were estimated at 12 killed and 15 wounded.”

10-year-olds enlisted by British

The Times of India, Oct 26 2015

UK enlisted Indian kids as young as 10 in WWI army

Britain's World War I army included Indian children as young as 10-years-old fighting against the Germans on the western front, according to a new book on the role of Indian soldiers in the Great War. The youngsters were shipped over to France from the far reaches of the British Empire to carry out support roles, but were so close to the front line that many were wounded and admitted to hospital, according to `For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front 1914-18'. The account by writer and historian Shrabani Basu is based on official papers at the National Archives and British Library . Some of the Indian children, including a 10-year-old “bellows blower“, and two grooms, both 12, provided support to cavalry regiments, a `Sunday Times' report said.

One of the youngest boys involved in direct combat was a “brave little Gurkha“ called Pim, 16, who was given an award for valour by Queen Mary while he was recuperating in hospital in Brighton.

Basu believes many of the children came from poor families and that they would have lied about their age at recruitment offices in India, where they were encouraged to sign up for a monthly salary of 11 rupees. “In the case of a 10-year-old, it should have been pretty obvious that they were underage,“ she told the newspaper.

This embarrassment was shared by some British offici als. In one dispatch to Lord Kitchener, secretary of state for war, Walter Lawrence, a civil servant tasked with overseeing injured Indian troops, wrote: “It seems a great pity that children should have been allowed to come to Europe.“ About 1.5 million Indian soldiers fought for Britain in the WWI, with a handful being awarded the Victoria Cross bravery medal.

Martyrs

Remembering them

A century on, World War I martyrs to be remembered

New Delhi

The Times of India Jul 29 2014

On July 28, 1914 Austria-Hungary fired the first shots to invade Serbia. Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination by a Serbian nationalist a month earlier had proved to be the final straw, even though tensions were escalating for quite some time. This set in motion a chain of events, with Britain declaring war on Germany on August 4, which triggered a conflagration the like of which the world had never witnessed till then. World War-I would last over four years, from 1914 to November 1918, with around nine million troops and many more civilians being killed.

Around 62,000 of them were Indian troops, with another 67,000 being wounded in the trench-to-trench warfare-the norm then. Over a million Indian troops, each paid Rs 11 per month, under the British flag took active part in World War-I, from Sonne and Flanders in France to Gallipoli and Canakkale in Turkey.

“An Independent India may not choose to remember the soldiers who laid down their lives since they were fighting for the British Empire. A soldier is a soldier, whichever the political dispensation that directs him to go to war may be,” said a major-general.All of the 30 regiments or units that took part in the “Great War” and are still part of the Indian Army, from Skinner’s Horse and Madras Regiment to Gorkha and Garhwal Rifles, commemorate their own “Battle Honour Days” in their own unique way.

Non-combatants

Radhika Singha’s research

Avijit Ghosh, January 8, 2021: The Times of India

‘Of the 1.4 million Indians who participated in World War I, over half a million were non-combatants’

The critical role of Indian army in World War I is well-known. What’s little known is over 5.5 lakh non-combatants – porters, cooks, sweepers, blacksmiths and others – were an important part of the ecosystem. Historian Radhika Singha of JNU has fleshed out their role in a book, The Coolie’s Great War. She explains her findings to Avijit Ghosh in an email interview:

How did you chance upon this subject?

In 2003-04 there were proposals to send an Indian contingent to support the American occupation of Iraq. As protests mounted I dipped into the archives to learn something about the sending of an Indian Expeditionary Force to Ottoman Iraq (Mesopotamia) in World War I. I found letter after letter desperately pressing for followers, including one marked secret which asked urgently for sweepers. Cholera had broken out in Basra, and these men were going to be placed in the thick of this epidemic front. This piqued my curiosity and I discovered that of the 1.4 million Indians who participated in World War I, over half a million were in fact non-combatants. But their particular form of work had not figured in the story.

Since many of the non-combatants came from the so-called ‘lower caste’ and ‘untouchables’, how did caste hierarchies play out?

In fact, the recruiting base for noncombatant units such as mule transport, stretcher bearers and the Labour Corps, and that for combatants, often overlapped. These were not always sharply distinct social strata. However, in World War I noncombatant recruitment had a wider spatial spread than for combatants. Jharkhand, for instance, provided Labour Corps for France, Mesopotamia and the North West Province. The hill districts of Assam and Burma sent Labour Corps to France, and for political reasons these were fore fronted in war propaganda. Bengal, UP, Bihar and Orissa, and the North Western Frontier Province also sent Labour Corps to this theatre. But these melted out of official sight on their return.

Caste in relation to work was of significance when it came to the so- called ‘attached’ or ‘menial’ followers, those who provided ‘domestic type’ services to regiments or military hospitals. Among them were the ‘untouchables’ who cleaned latrines, laundered clothes, and repaired leather boots and saddles. Here the recruiting pool was narrower. Non-combatant units leveraged the manpower hunger of the war to secure an improvement in wages and benefits, but change was more limited for these ‘menial’ followers. However ‘low caste’ followers managed sometimes to pick up less stigmatised work as ward ‘boys’ in the hospital, khidmatgars (valets) or even as cooks for British messes.

Interestingly, the pressing need for manpower ensured that both combatant and non-combatant had to be used more rationally. High caste soldiers began to be organised into platoon based messes, and were put to a wider range of ‘fatigue’ duties.

How many Indian army men and non-combatants died in World War I?

War Office statistics for the period up to December 31,1919, put the figure for Indian casualties at 62,056. Another table gives the following break up: 764 for Indian officers, 35,313 for the Indian other ranks, and 17,419 for the Indian followers. We don’t have figures for morbidity due to malaria or respiratory disease which would have revealed much more about the impact of war upon the follower ranks.

What is the most poignant story you came across?

To improve their institutional standing, non-combatants sought to create suggestive equivalences between themselves and other military personnel. They wanted to show that they hadn’t just come for food and wages, but were rendering ‘war service’. So we find the 26th Lushai labour company in France donating all their canteen profits for a war charity, and a Kumaon labour company giving its entire store of tea to an incoming British party and allowing bully beef to be heated in their tent. As they explained to their officer, “Sahib this is war time.” Some conversational snatches were both revealing and very moving. A Muslim cavalryman wrote home to complain about the shocking effect which France and the attentions of the YMCA had had on regimental followers. The sweeper of his troop had said, “God has dealt very harshly with me in that while at heart I am a citizen of this country (that is France), he caused me to be born in Hindustan and hence I have to pass my days in contemptible occupation. These people consider everything lawful for food ... and I am the same … They remove dirt with their own hands and so do I. Therefore I am in a very unfortunate position.”

What happened to the followers after they came back?

It is difficult to trace returning followers because many of the labour units were temporary formations. Service benefits followed the pattern of military hierarchy: the most for Indian officers, less for rank and file soldiers, and the least for the follower ranks.

Indians who lorded over European skies in WWI

Manimugdha S Sharma,TNN | Oct 8, 2014 The Times of India

The First World War had 1.3 million Indians fighting in every theatre of the conflict. A handful of them fought in the air, and one of them became the first Indian fighter ace. Yet outside the Indian Air Force, which celebrated its 82nd anniversary on Wednesday, there seems to be little awareness about the role of India's air warriors in the Great War.

Gurdit Singh Malik

It all started with a Sikh student studying in Oxford expressing his wish to join the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in 1917, when the war had reached a crescendo. Sardar Gurdit Singh Malik was initially denied permission to join the force; he was instead asked to serve as an orderly in an Indian military hospital. "He had to overcome institutional racism to become a fighter pilot for the British before he took on the Germans," said Harbakhsh Grewal of UK Punjab Heritage Association, one of the organizers of the widely acclaimed 'Empire, Faith, War: The Sikhs and World War One' exhibition in Britain.

A disappointed Malik then went to France to help out the beleaguered French as an ambulance driver. There, too, he asked if he could volunteer in the air force. The French agreed. Malik then wrote to his tutor in Oxford about it, who then took it up with the chief of the RFC and said it would be an embarrassment if a British subject had to be employed by the French. "That's when I heard from General Henderson, chief of RFC, who asked me to see him. After that meeting, I was sent for training and got a commission in the RFC as a fighter pilot," Malik had said in a TV interview in the early 1980s. Malik became the first Indian fighter pilot of the RFC, which became the Royal Air Force during the war. With a precedent thus set, the RFC opened its doors to Indians.

Malik shot down six German fighters in those early days of aerial combat when fighter pilots tried to shoot each other down with pistols and rifles when they came too close to each other. The life expectancy of fighter pilots in those days was just 10 days in combat. Yet Malik survived the war despite being wounded in action.

Malik's squadron also duelled with Manfred von Richthofen, the famous 'Red Baron'. But despite his kills, Malik was officially credited with only two and missed out on the title of 'ace' (a pilot who downed five or more enemy aircraft). That credit went to another Indian pilot, Lieutenant Indra Lal "Laddie" Roy.

Lt Indra Lal Roy

Roy was studying in London and had just turned 18 when he volunteered for the RFC. He got a commission and was placed with no. 56 squadron first before being transferred to no. 40 squadron. In just 170 hours of flying, Roy shot down 10 enemy aircraft, thus becoming a full ace. Roy didn't survive the war. He was shot down in July 1918, aged just 19. He was awarded with a Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously.

Two other Indian pilots who saw action on the Western Front were Lieutenant Srikrishna Welingkar and Lieutenant Eroll Chunder Sen. Welingkar, like Roy, didn't survive, while Sen became a German PoW, released only after the war. Malik joined the Indian Civil Service and had a distinguished career. He became Independent India's first high commissioner to Canada, and Jawahalal Nehru is believed to have made him Indian ambassador to France to use his goodwill among the French to settle the return of French colonies to India. Britain, however, always remembered Malik as the "turbaned young fighter pilot who shot down Germans in the air".

Indian solders in World War 1

Their experience in Europe

For 15 years, Belgian historian Dominiek Dendooven has studied the presence of colonial troops on the Western Front in the First World War. That has made him a leading European expert on the Indian experience of the war. In India with the royal delegation to commemorate this country’s WWI role, he spoke to Manimugdha S Sharma

When Britain deployed Indian troops on the Western Front in 1914, Germany said that this would upset the racial balance. Did it really?

The British view on race wasn’t very different from the German one. Their decision to deploy Indian troops had raised eyebrows even in Britain. But they couldn’t have possibly found another standing army in the dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. The only other properly trained fighting force that could have buttressed the British Army was the Indian Army. So, wartime exigency trumped racial considerations.

However, when there were white troops available in sufficient numbers, Indian infantry was withdrawn in 1915-end and the Indian labour corps was brought in. So ultimately, an effort was made by the British to restore the old race hierarchy — coloured troops as menial labourers and whites as fighting men on European soil

But the French were different, weren’t they? Their black Senegalese tirailleurs (infantrymen) fought on the Western Front longer than the Indians.

Absolutely. And this is where the French differed from the British. Now, this isn’t an argument in favour of French colonialism but the French colonial project had one long-term objective — to make the colonials entirely French. So, a Senegalese could say he was a French citizen. In contrast, an Indian was forever a British subject, not a citizen. You would find this even in the relationship between the Indian troops and the British officers. The white officers were paternalistic towards their men.

To what extent did Indians face racism in Europe?

To a great extent. Glorious and exemplary actions by Indian troops were overlooked by the British. And those who were wounded and sent to England to recuperate were closely guarded to avoid liaisons with British women. It didn’t always help. And we know from letters that the Indians did have affairs with white women in Britain. But there was extreme fear that these amorous relationships would degrade white supremacy and upset the social hierarchy maintained by the Raj.

There is this particular incident of an Indian soldier cohabiting with a Frenchwoman and having children with her. When the Indians were withdrawn, he left too. But the woman’s French husband returned home and told her that such things are part of life. He raised the children as his own. His grandson later wrote in his memoir that he was proud of both his grandfathers: the Indian who broke taboo and had children with a whitewoman, andtheFrenchman who raised the Indian man’s kids as his own.

How did Europe influence these Indians?

Remember that these men who went to Europe were commoners, not royalty. They saw “sahib log” toil in the fields, do the dishes, even clean the rooms in which they were staying. This busted the myth that the whites are only the ruling class. The second thing was, of course, that the myth of white invincibility got smashed. It was the Indian troops who had helped stop the Germans from reaching the channel ports. Europe and the world would have been a different place without the Indians at France and Flanders.

But there was something else that happened. The Indians saw an industrial war for the first time. But amid all that destruction, many of them resolved to go back home, open English-medium schools, and educate their daughters. The Indians were very impressed to see educated European women. You still have so many schools in Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh started by men returning from the war. So, this was a great positive that was born in the killing fields of Flanders.

Are you happy with the way commemoration events are happening?

Yes and no. Yes, because I am very glad that India is commemorating her WWI role. You must claim your rightful place in history. And that can happen if the government is officially more proactive. But at the same time, I think around the world we are seeing a commemoration imperialism. The British narrative of thewar is all about them. Their commemorations are also largely about them.The Australians think it’s all about them. This isn’t right.

Wounded Indian troops sent to recuperate in England were closely guarded to avoid liaisons with British women. It didn’t always help

Indian soldiers were not mercenaries: Vedica Kant

Dec 24 2014

In WWI, Indian soldiers proved a match for Germans 30 years later, India was independent

Vedica Kant from Oxford University has authored a book on India and World War I, titled “If I die here, who will remember me?” Speaking with Manimugdha S Sharma, Kant discussed why India must commemorate Indian soldiers who fought in the great war, how exposure to the West changed Indian minds and a crucial link between WWI and Indian freedom: Is WWI's centenary important for India?

The centenary is not about celebration it's about remembrance. The fact is, nearly one and a half million Indians took part. The world we know today was also shaped by them. We can't just write them out of history . We must accept them as part of our history we have to talk about them.

Many people, including Justice Markandey Katju, seem to think Indian soldiers who participated were mercenaries and need no remembrance your view?

That mercenary argument doesn't hold water because as soldiers they had the same motivations soldiers have today pay , honour and attachment to their regiment and fellow soldiers. These Indians were professional soldiers with years of fighting experience.

In addition, they often felt they were doing their duty by fighting for the Empire people like Mahatma Gandhi, Tilak and others thought that by sending troops to fight the war, India would prove worthy of demanding dominion status and put Britain under a moral debt to grant home rule they recruited people for the war.

People who went to war with the backing of people of this country can't be called mercenaries.

Indian soldiers went to the western front, exposed to a new kind of war and setting how did this impact them?

The Indian soldier, for the first time, upset the racial hierarchy that European powers maintained in their colonies. It was an unwritten convention that only white soldiers would be fielded against white troops in Europe Britain and France broke this convention, out of dire need, if nothing else. Germany protested against this.

Indian soldiers had very receptive minds. They could spot how advanced Europe was, how economically better off its people were. They understood how worse off they were. But there was another realisation that the Indian soldier wasn't inferior to any white soldier. In fact, he was proving more than a match for the German soldier. This realisation gave a sense of equality, a new confidence in his abilities.

This individual experience combined with a global milieu in which self determination was climbing up the agenda it also impacted the freedom movement back home in India.

In 30 years from World War I, India became independent.

Many Indian soldiers formed relationships with European women did this change them?

Indian soldiers noticed white women were educated. They also took up jobs left by men who went to war. This impressed the troops very much. Many wrote home about it, telling their families how important it was to be educated. Many talked about educating their girl children equally as boys.

This wasn't just a passing thought, after the war, many came home and sent their girls to school.

‘For them the army was like a university’: Morton-Jack

From: For Indian sepoys who served in WWI, the army was like a university, November 10, 2018: The Times of India

The centenary of World War I draws to a close on Sunday, exactly 100 years after Armistice Day on November 11, 1918. British historian George Morton-Jack throws new light on that era in his book, The Indian Empire at War: From Jihad to Victory, the Untold Story of the Indian Army in the First World War. India sent 1.3 million people to serve in what are today 50 different countries. The author tells Manimugdha S Sharma why the popular narrative about their role in the war needs to be questioned

The old Indian Army was a “peasants’ university”, you write in your book quoting a British civil servant. Could you elaborate?

The idea was stated by the civil servant, Malcolm Darling. His idea was that the army should be seen from the point of view of young villagers joining up in their late teens — through the army they left home for the first time, gained wider experience and new ideas. The army could teach them basic literacy through cantonment schoolhouses and lessons in self-discipline. They came back from Europe, Africa and West Asia after WWI with broadened horizons, and better able to understand the world and their place in it comparatively. They had seen in France primary education for girls in villages, or different styles of everyday clothing in East Africa, which they could then compare with life at home. As one veteran said, “The sepoy has seen the world.” A common conclusion among them was that the white societies of Europe were freer than their own, and they saw a lesson in that — why should India not be free?

You say the Indian Army was trained using the same drills and manuals of the British Army, including mountain warfare. So what do you think of the argument forwarded by some that the Indians were ill at ease fighting on the Western Front and gave a poor account of themselves?

The argument disregards the professionalism and adaptability of the Indian Army of 1914, and does not address the roots of such arguments in colonial narratives of Indians as racial inferiors and, therefore, weaker in battle. As the wartime Indian diarist Captain Amar Singh commented in France in 1915, British soldiers fled the battlefield like the Indians did at times. And yet, whatever the Indians did, the British would not see them as equals.

Was the loyalty of Indian troops as rocksolid as it is often claimed?

The idea of rock-solid Indian loyalty was certainly rooted in a British need as colonial rulers to portray Indian troops as loyal. The Indian troops’ own view of themselves was much more ambiguous — their loyalty has been compared to a coin, one side facing the British with expressions of loyalty, the other side more inward-looking, with feelings of resentment at being denied senior command, for instance, and of wanting racial equality denied to them as colonial subjects. The issue of their loyalty has many shades of grey and remains delicate.

What are your views on the varying narratives built around the two brothers who won honours from opposing sides in the war? Mir Dast was a Victoria Cross winner and Mir Mast switched loyalty to the Germans. Was it as black and white as it is often claimed?

The varying narratives can deceive through their repetition down the years. For instance, Mir Mast has long been said to have won the Iron Cross — an old frontier rumour. He, in fact, was awarded the Order of the Red Eagle for diplomatic service to Germany. The Iron Cross narrative is a myth that arose to contrast him with his brother. Then again, Mir Dast deserted the Indian Army in 1917 — clearly he was not quite the loyal counterpoint to his brother that he has been said to be. The brothers were independent Afridis, and understanding this is the key to their story.

The Indian Muslims fought like true professionals at Gallipoli, Turkey, and yet their loyalty was doubted by the British.

The central issue is how the central authority (the regime) views a peripheral minority or outsider — in most countries, they are mistrusted, whether in 1918 or 2018.

You say that you disagree with the statement that the Indian contribution has been forgotten. Why?

There has been a significant amount of writing on Indian troops from 1917 onwards, more than on Africans in British service. Hundreds of war memorials to the Indians since 1917 remain in place today from England to India. It is more realistic to say the Indians of 1914-18 have been traditionally neglected compared to other troops who have received more attention. From 2014 to 2017, the Indians received a great deal of attention, making it less likely that they will be forgotten.

Commemorating India’s WWI role

A century after the war

Manu Pubby

December 10, 2014

It has taken a century to capture the extraordinary tales of over a million Indians who sailed far from home, defying tradition and even religious belief, to take part in a war they did not understand, in a land they did not care about and against an enemy they had never met. There will always be a debate on whether the Indian contribution to World War I strengthened England's colonial grip and postponed an inevitable independence, but that does not take away anything from the amazing contribution of the soldiers who bravely fought in the deceptively welcoming fields of Flanders and the burning heat of Mesopotamia.

On the centenary of the First War, two books have gone deep into the fascinating Indian military role that can barely be imagined now. The entire strength of the present Indian Army and more would be needed to match the 1.38 million-strong force that left the shores of the country a century ago. Vedica Kant's If I die here, who will remember me?: India and the First World War goes into the narrative of the war from the political motivation to the challenges faced by Indian soldiers.

But where it is most engrossing is in the way it has captured the life of the soldier, from the culture shock he got in Europe to his questioning of the racial hierarchies in colonial rule. Peppered with rare photographs of troops engaged in things as mundane as preparing food to a trench deployment and the deeply moving picture of an Indian prisoner of war in a camp in Wunstorf that is also mentioned by writer Amitav Ghosh in the foreword, Kant's book captures the life, the battles and even the loves of the Indian soldier.

The book that goes into the precise military details of the battle, reconstructing the action of the seven Expeditionary Forces that went into several theatres of war between 1914 and '18, is Amarinder Singh's Honour and Fidelity: India's Military Contribution to the Great War. The soldier-politician has dug deep into his family records, official documents and the immaculately maintained records of the regiments that went to war. For the military enthusiast, the book contains delicious details, such as the cunning move by Naik Ayub Khan of the 129 Baluch Regiment to reach a particularly difficult German trench, claiming to be a deserter who can get more men to cross over and gathering vital defence informa-tion in the bargain for his battalion.

Singh's book brings out the massive military contribution of Indian soldiers and how it changed the tide of the war for the Brit-ish who were struggling in France with its British Expeditionary Force (BEF). It was on the verge of collapse before being propped up by the Indian Corps.

The four years of battle cost 74,000 Indian lives. Singh says that he decided to write the book after he got livid over how little the Indian con-tribution was acknowledged. "In a 12-part series that the BBC did on the war a few years ago, India's contribution was found fit to be shown for only one minute. One minute in 23 and a half hours of programming!" he says.

Kant's book will appeal both to a first-time reader of the war as well as a battle fanatic as it comes up with surprises every few pages. One such is a two-page section called 'Sex and Romance in France' that speaks of the fleeting, sometimes transactional, relationships that Indian soldiers had with French women.

Mahomed Khan, a trooper from the 6th Cavalry, married a Frenchwoman despite apprehensions from his family back home. He eventually told them that the king had ordered him to marry.

Kant also captures the astonishing tale of the Mir brothers. While Mir Dast was the recipient of a Victoria Cross for gallant action during a gas attack, his brother Mir Mast deserted and went to the Germans with 24 others to undertake anti-British activities. Another section on religious imagery in the war reveals how Indian soldiers described the battles they fought in letters back home with religious references from the Mahabharat as well as the Quran.

Kant's book has liberally used first-hand accounts of the war-from letters sent by soldiers to archives and POW camp records-to reveal the minds of the men who faced extraordinary challenges, even beyond the primary task of war fighting.

However, for the gritty details of fighting from tactics to innovations in the battlefield and inspiring leadership-Singh's book is unbeatable. The politician has always had a soldier in him and like his previous accounts of war-from the Kargil war to the three battles of India since Independence-he proves his credentials as one of the country's finest military writers. The painstaking details through which he chronicles the actions of the forgotten men stand out and are a befitting tribute to their contribution. From France to East Africa, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Gallipoli, the battlefields come alive. For instance, the description of the battle against the Turkish forces at Kut in Mesopotamia is beefed up with sketches and a blow-by-blow account. One particular day, Singh writes, of the 255 Indian officers who went to battle, 111 became casualties.

It is interesting to note that the two very different books on the war at one point were meant to be one consolidated work. Singh says that initially the plan was to bring together a single narrative along with Kant, but the project became unwieldy. The reader has a choice-to pick one or the other. But to fully relive the experience of a war fought a century ago, both books are a must-read.

See also

World War I and India

and many more...