Taxes: India

(→Tax revenue, gross (GTR)) |

(→Tax to GDP ratio) |

||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

=Tax to GDP ratio= | =Tax to GDP ratio= | ||

==2008 – 23== | ==2008 – 23== | ||

| − | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/the-revenue-record/ Krishnamurthy Subramanian, Nov | + | [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/the-revenue-record/ Krishnamurthy Subramanian, Nov 27, 2023: ''The Times of India''] |

| − | [[File: Tax to GDP ratio in India, 2008 – 23.jpg| Tax to GDP ratio in India, 2008 – 23 <br/> From: [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/the-revenue-record/ Krishnamurthy Subramanian, Nov | + | [[File: Tax to GDP ratio in India, 2008 – 23.jpg| Tax to GDP ratio in India, 2008 – 23 <br/> From: [https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/the-revenue-record/ Krishnamurthy Subramanian, Nov 27, 2023: ''The Times of India'']|frame|500px]] |

'''See graphic''': | '''See graphic''': | ||

| Line 140: | Line 140: | ||

TAXES: INDIA]] | TAXES: INDIA]] | ||

[[Category:Pages with broken file links|TAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIA | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|TAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIA | ||

| + | TAXES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Economy-Industry-Resources|T TAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIA | ||

| + | TAXES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:India|T TAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIA | ||

| + | TAXES: INDIA]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Pages with broken file links|TAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIATAXES: INDIA | ||

TAXES: INDIA]] | TAXES: INDIA]] | ||

Revision as of 22:49, 1 December 2023

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

1995-2017

From: The Times of India, Feb 2, 2017

See graphic:

The share of direct taxes, service tax, excise duty and customs duty in the total tax collections of India, 1995-2017

1950-2021

From: February 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The share of direct and direct, corporate and income taxes in the total tax collections of India, 1950-2021

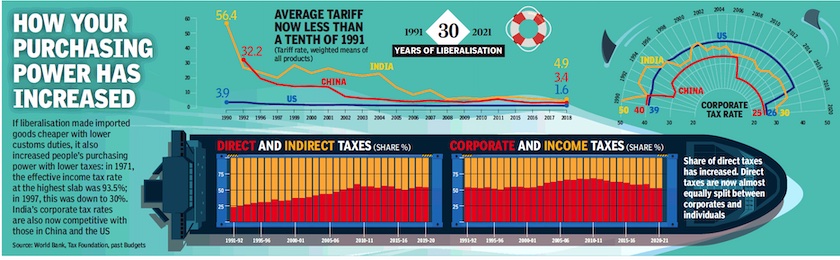

1991-21

The Share of direct, corporate, income taxes;

Tariff rates.

From: February 1, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

1991-21

The Share of direct, corporate, income taxes;

Tariff rates.

1991-21/ B

Atul Thakur & Rema Nagarajan TNN, January 30, 2023: The Times of India

From: Atul Thakur & Rema Nagarajan TNN, January 30, 2023: The Times of India

The word ‘taxpayer’ is routinely used by middle class Indians to refer to those who pay income tax, but the biggest chunk of the government’s tax revenue actually comes from goods and services tax (GST), which is paid by even the poorest. This is followed by corporation tax, paid by corporates on their profits, though individual income tax is a close third.

The 2022-23 Budget estimate of revenue earned from GST was Rs 7. 8 lakh crore compared to Rs 7. 2 lakh crore from corporation tax and Rs 7 lakh crore from income tax. The actual revenue in 2020-21, the Covid year, saw GST netting Rs 5. 5 lakh crore. Corporation tax yielded just Rs 4. 6 lakh crore — lower than the income tax collection of Rs 4. 9 lakh crore, thanks to the impact of the pandemic on corporate revenues and profits. Indirect taxes, which are paid by all citizens, whether rich or poor, include GST, customs & excise duties and the erstwhile service tax. In India, indirect taxes constitute about half of total taxes collected. Tax systems with a high component of indirect taxes are considered regressive since the burden of such taxes falls on everyone irrespective of their capacity to pay unlike direct taxes such as taxes on income or on profits of companies, which only apply to those with incomes above a threshold level or to firms that are profitable.

Developed nations mostly collect tax revenues from direct taxes. “Among OECD countries, indirect taxes (such as VAT and GST) account for about one-third of total tax revenues. The bulk of their tax revenues (roughly 66%) come from direct taxes such as income, corporate, property, payroll taxes, etc,” pointedout Reetika Khera, professor of economics at IIT-Delhi.

At the time of independence, India was struggling to generate revenue as there were very few corporates and only a small tax base of individual taxpayers. Hence, through the 1950s and right up till the 1990s, up to 80% of revenue was generated fromindirect taxes. Subsequently, the share of indirect taxes dropped to its lowest (41%) in 2009-10, but has risen since then (see graphic) , though Budget estimates suggest this will change. Also, the share of individual income tax within direct taxes has risen after falling.

According to the receipts in Budget 2022-23, there were 6. 3 crore individuals who filed income tax returns for the financial year 2019-20. The annual report of the periodic labour force survey for the period from July 2020 to June 2021, released in June 2022, said only 41. 6% of India’s total population, or 56 crore, people are “usually employed” or looking for work. That means, only about 11% of the labour force file income tax returns. With poor quality employment and low wages, the proportion of those earning more than Rs 2. 5 lakh per annum or about Rs 21,000 a month, the level above which income tax applies, is very small. According to government’s data in assessment year 2018-19 (the last for which such data is available) a little over 40% of individuals filing income tax returns (5. 5 crore people) had zero tax liability. Thus, only about 3. 3 crore individuals actually paid any income tax, just under 6% of the labour force. There would of course be many evading taxes, but the bulk of India’s population simply doesn’t earn enough to even fall within the tax bracket.

Meanwhile, the tax rate on corporates has steadily come down from 50% in the 1990s to 30%, which is in line with many large economies —about 25% in China and the US, and about 30% in Germany and Japan. India tries to keep corporate taxes low to keep it competitive internationally. But this, along with a very low individual income tax base, means boosting the share of direct taxes in the total tax kitty is a tall ask.

2014-22

Atul Thakur, Oct 13, 2022: The Times of India

Since the financial year 2020-21 – the first to be completely impacted by the pandemic – the share of indirect taxes in the Centre’s total tax collections has risen above 50%. Unlike direct taxes – like income tax and corporation tax, which are based on income – indirect taxes like customs, excise and so on are paid by both rich and poor.

Further analysis of the data shows the increase in the share of indirect taxes in the government’s overall tax collection seems to be linked to the increased tax collection from petroleum products. In 2014-15, the year since when data on tax collection from petroleum is available, the Centre had Rs 12. 5 lakh crore of gross tax collections. Of this, Rs 6. 9 lakh crore came from corporation and income taxes, constituting 55. 2% of the total. Another Rs 5. 5 lakh crore was collected through major indirect taxes, which was 44. 4% of the total tax collection.

Since 2014-15 there has been a steady decline in the share of corporation taxes in the Centre’s overall tax collection. From 34. 5% in 2014-15, it fell to 22. 6% in 2020-21. There has been an increase since 2020-21, but at 25. 2% the share of corporation tax in gross taxes is still signifi cantly lower than in 2014-15.

During the same period, the share of income tax in gross tax collections increased from 20. 8% in 2014-15 to over 24% in 2019-20 and has remained around that level. This increase of about 3 percentage points, however, has been too small to offset the over 9 percentage-point fall in the share of corporation taxes. Despite this, except for 2016-17, the share of direct taxes (corporation tax plus income tax) remained more than 50% of the central government’s total tax collections, till the trend was reversed in 2020-21. The period since 2014-15 has seen a relatively steady increase in the share of indirect taxes. From 44. 4% in 2014-15 the share increased to 53. 1% in 2020-21. Although there was a slight drop in 2021-22, indirect taxes’ share of 50% in total collections was still about 5. 6 percentage points higher than its 2014-15 value. Apart from the fall in corporatetax’s share, the other factor that has pushed up the share of indirect taxes is the increase in taxes on various In 2014-15 the central exchequer collected Rs 1. 3 lakh crore as taxes on various petroleumproducts. This was 22. 8% of the government’s total indirect tax collection. Since then every successive year saw a rather steady increase inpetroleum’s contribution in indirect taxes. From 22. 8% in 2014-15, the share increased to 39% in 2020-21. There has been a decline since then to 34. 3% in 2021-22, but that’s still much higher than the 2014-15 level.

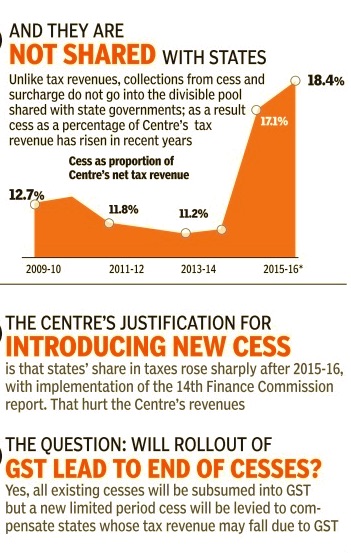

2009-16

From: The Times of India, Feb 2, 2017

See graphic:

Cess as proportion of centre's net tax revenue, 2009-16 and impact of GST on imposition of cesses

2009-19

From: The Times of India, Feb 2, 2017

See graphic:

Cess in Indian economy and revenue collection from cesses, 2009-17 and cesses and surcharges that fetch over Rs. 1000 crore annually

Tax collection

2015-16

From: The Times of India, Feb 11, 2017

See graphic:

%change in industrial production and tax collection ,2015-16

2011-21

From: April 19, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

Tax receipts, direct and indirect, India: 2011-21

Tax revenue, gross (GTR)

2003- 18, 22

January 30, 2023: The Times of India

From: January 30, 2023: The Times of India

During the last 22 years, there have been only two occasions - 2006-07 to 2007-08 and 2015-16 to 2017-18 - when the actual collections have been more than the Budget estimates (BE) during successive years.

Against a Budget estimate of Rs 15. 5 lakh crore, the Centre’s net revenue collections (after transfers to states) were estimated atover Rs 18 lakh crore, according to the provisional data available with the Controller General of Accounts. During the current fiscal year too, direct tax and GST collections are on course to beat the BE.

Tax to GDP ratio

2008 – 23

Krishnamurthy Subramanian, Nov 27, 2023: The Times of India

From: Krishnamurthy Subramanian, Nov 27, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Tax to GDP ratio in India, 2008 – 23

Tax-to-GDP ratio, a critical economic metric, has increased over the last few years. That’s very good news. Govt’s next goals should be a simple tax code & a system to tax self-employed professionals

Every month, we read about record numbers of Goods and Services (GST) tax collections. The transformative changes in India’s tax situation are actually the outcome of sagacious policy. In economic governance, few metrics hold as much significance as the tax-to-GDP ratio. More than a mere statistic, it reflects a nation’s fiscal health, its ability to finance necessary infrastructure and public services.The story of tax collection over the past decade in India is one of remarkable transformation. As shown in the figures below, from 2008 till 2015-2016, the country witnessed a gradual decline in tax-to-GDP ratios, both direct and indirect. Remember that as the effect of economic policies always manifests with a lag, the reduction till 2016 stemmed from the economic troubles post the global financial crisis, where India became part of the Fragile-5 economies.However, the tables started turning after the current government embarked on a series of decisive reforms that revitalised the nation’s tax collection, catapulting it to a more robust economic trajectory. This is reflected in the slope of the absolute tax revenues increasing sharply from 2016 onwards. While there was a blip during the years of the once-in-a-century pandemic, the momentum gathered before Covid has resumed.

Direct taxes encompass income and corporate tax. From 2008 to 2014, India saw a consistent dip in the direct-tax-to-GDP ratio from over 6% in 2008 to about 5.5% in 2016. However, the current government’s commitment to simplifying the tax structure, promoting digitalisation, and widening the tax base has brought about a significant change.Remarkably, the increase of the direct-tax-to-GDP ratio to over 6% has occurred despite a significant reduction in corporate tax rates in September 2019. This phenomenon is consistent with the theory of the Laffer curve in economics, which suggests that there is an optimal tax rate at which tax revenue is maximised. As India’s corporate tax rates were much higher than optimal before 2019, the reduction in corporate tax rates was a good move as it was aimed at boosting investment and economic growth. As the evidence shows, this reduction in tax rates, while benefiting businesses and thereby the economy, has not hampered direct tax collection, thereby validating the sagacity of the policy change. The momentum generated by this policy change will be felt even more strongly as the economy gathers more pace.

The indirect-tax-to-GDP ratio, which covers taxes on goods and services, paints a similar story. It saw a slump from 2008 to 2014-2015. The implementation of GST, which reduced the effective tax rate by eliminating cascading taxes, is equally consistent with the theory of the Laffer curve.The government has expanded the taxpayer base through initiatives like ‘Vivad se Vishwas’ and has brought greater efficiency through ‘Faceless Assessment’. Anti-evasion measures such as data analytics and advanced technology have been deployed to detect tax fraud and ensure compliance. The digitalisation of the tax collection process has also reduced opportunities for tax evasion.

The writer is former chief economic adviser to GoI