Kammālan

(Created page with " {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article is an excerpt from<br/> ''' Castes and Tribes of Southern India ''' <br/> By '' Edgar Thurston,...") |

(→Kammālan (Tamil)) |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

“The idol-maker’s craft, like most of the other callings in this country, is a hereditary one, and a workman who has earned some reputation for himself, or has had an ancestor of renown, is a made man. The Sthapathi, as he is called in Sanskrit, claims high social rank among the representatives of the artisan castes. Of course he wears a heavy sacred thread, and affects Brāhman ways of living. He does not touch flesh, and liquor rarely passes down his throat, as he recognises that a clear eye and steady hand are the first essentials of success in his calling. There are two sorts of idols in every temple, mulavigrahas or stone idols which are fixed to the ground, and utsavavigrahas or metal idols used in processions. In the worst equipped pagoda there are at least a dozen idols of every variety. They do duty for generations, for, though they become black and begrimed with oil and ashes, they are rarely replaced, as age and dirt but add to their sanctity. But now and then they get desecrated for some reason, and fresh ones have to be installed in their stead; or it may be that extensions are made in the temple, and godlings in the Hindu Pantheon, not accommodated within its precincts till then, have to be carved and consecrated. It is on such occasions that the hands of the local Sthapathi are full of work, and his workshop is as busy as a bee-hive. In the larger temples, such as the one at Madura, the idols in which are to be counted by the score, there are Sthapathis on the establishment receiving fixed emoluments. | “The idol-maker’s craft, like most of the other callings in this country, is a hereditary one, and a workman who has earned some reputation for himself, or has had an ancestor of renown, is a made man. The Sthapathi, as he is called in Sanskrit, claims high social rank among the representatives of the artisan castes. Of course he wears a heavy sacred thread, and affects Brāhman ways of living. He does not touch flesh, and liquor rarely passes down his throat, as he recognises that a clear eye and steady hand are the first essentials of success in his calling. There are two sorts of idols in every temple, mulavigrahas or stone idols which are fixed to the ground, and utsavavigrahas or metal idols used in processions. In the worst equipped pagoda there are at least a dozen idols of every variety. They do duty for generations, for, though they become black and begrimed with oil and ashes, they are rarely replaced, as age and dirt but add to their sanctity. But now and then they get desecrated for some reason, and fresh ones have to be installed in their stead; or it may be that extensions are made in the temple, and godlings in the Hindu Pantheon, not accommodated within its precincts till then, have to be carved and consecrated. It is on such occasions that the hands of the local Sthapathi are full of work, and his workshop is as busy as a bee-hive. In the larger temples, such as the one at Madura, the idols in which are to be counted by the score, there are Sthapathis on the establishment receiving fixed emoluments. | ||

| − | + | Despite the smallness of the annual salary, the office of temple Sthapathi is an eagerly coveted one, for, among other privileges, the fortunate individual enjoys that of having his workshop located in the temple premises, and thereby secures an advertisement that is not to be despised. Besides, he is not debarred from adding to his pecuniary resources by doing outside work when his hands are idle. Among stone images, the largest demand is for representations of Ganapati or Vignesvara (the elephant god), whose popularity extends throughout India. Every hamlet has at least one little temple devoted to his exclusive worship, and his shrines are found in the most unlikely places. Travellers who have had occasion to pass along the sandy roads of the Tanjore district must be familiar with the idols of the god of the protuberant paunch, which they pass every half mile or so, reposing under the shade of avenue trees with an air of self-satisfaction suffusing their elephantine features. Among other idols called into being for the purpose of wayside installation in Southern India, may be mentioned those of Vīran, the Madura godling, who requires offerings of liquor, Māriamma, the small-pox goddess, and the evil spirit Sangili Karappan. Representations are also carved of nāgas or serpents, and installed by the dozen round the village asvatha tree (Ficus religiosa). | |

Almost every week, the mail steamer to Rangoon takes a heavy consignment of stone and metal idols commissioned by the South Indian settlers in Burma for purposes of domestic and public worship. The usual posture of mulavigrahas is a standing one, the figure of Vishnu in the Srirangam temple, which represents the deity as lying down at full length, being an exception to this rule. The normal height is less than four feet, some idols, however, being of gigantic proportions. Considering the very crude material on which he works, and the primitive methods of stone-carving which he continues to favour, the expert craftsman achieves quite a surprising degree of smoothness and polish. It takes him several weeks of unremitting toil to produce a vigraha that absolutely satisfies his critical eye. I have seen him engaged for hours at a stretch on the trunk of Vignesvara or the matted tuft of a Rishi. The casting of utsavavigrahas involves a greater variety of process than the carving of stone figures. The substance usually employed is a compound of brass, copper and lead, small quantities of silver and gold being added, means permitting. The required figure is first moulded in some plastic substance, such as wax or tallow, and coated with a thin layer of soft wet clay, in which one or two openings are left. When the clay is dry, the figure is placed in a kiln, and the red-hot liquid metal is poured into the hollow created by the running out of the melted wax. The furnace is then extinguished, the metal left to cool and solidify, and the clay coating removed. | Almost every week, the mail steamer to Rangoon takes a heavy consignment of stone and metal idols commissioned by the South Indian settlers in Burma for purposes of domestic and public worship. The usual posture of mulavigrahas is a standing one, the figure of Vishnu in the Srirangam temple, which represents the deity as lying down at full length, being an exception to this rule. The normal height is less than four feet, some idols, however, being of gigantic proportions. Considering the very crude material on which he works, and the primitive methods of stone-carving which he continues to favour, the expert craftsman achieves quite a surprising degree of smoothness and polish. It takes him several weeks of unremitting toil to produce a vigraha that absolutely satisfies his critical eye. I have seen him engaged for hours at a stretch on the trunk of Vignesvara or the matted tuft of a Rishi. The casting of utsavavigrahas involves a greater variety of process than the carving of stone figures. The substance usually employed is a compound of brass, copper and lead, small quantities of silver and gold being added, means permitting. The required figure is first moulded in some plastic substance, such as wax or tallow, and coated with a thin layer of soft wet clay, in which one or two openings are left. When the clay is dry, the figure is placed in a kiln, and the red-hot liquid metal is poured into the hollow created by the running out of the melted wax. The furnace is then extinguished, the metal left to cool and solidify, and the clay coating removed. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:35, 2 April 2014

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

[edit] Kammālan (Tamil)

The original form of the name Kammālan appears to have been Kannālan or Kannālar, both of which occur in Tamil poems, e.g., Thondamandala Satakam and Er Ezhuvathu, attributed to the celebrated poet Kamban. Kannālan denotes one who rules the eye, or one who gives the eye. When an image is made, its consecration takes place at the temple. Towards the close of the ceremonial, the Kammālan who made it comes forward, and carves out the eyes of the image. The name is said also to refer to those who make articles, and open the eyes of the people, i.e., who make articles pleasing to the eyes. A very interesting account of the nētra mangalya, or ceremony of painting the eyes of images, as performed by craftsmen in Ceylon, has been published by Mr. A. K. Coomaraswamy.69 Therein he writes that “by far the most important ceremony connected with the building and decoration of a vihāra (temple), or with its renovation, was the actual nētra mangalya or eye ceremonial. The ceremony had to be performed in the case of any image, whether set up in a vihāra or not. Even in the case of flat paintings it was necessary. D. S. Muhandiram, when making for me a book of drawings of gods according to the Rupāvaliya, left the eyes to be subsequently inserted on a suitable auspicious occasion, with some simpler form of the ceremony described.

“Knox has a reference to the subject as follows. ‘Some, being devoutly disposed, will make the image of this god (Buddha) at their own charge. For the making whereof they must bountifully reward the Founder. Before the eyes are made, it is not accounted a god, but a lump of ordinary metal, and thrown about the shop with no more regard than anything else. But, when the eyes are to be made, the artificer is to have a good gratification, besides the first agreed upon reward. The eyes being formed, it is thenceforward a god. And then, being brought with honour from the workman’s shop, it is dedicated by solemnities and sacrifices, and carried with great state into its shrine or little house, which is before built and prepared for it.’” The pupils of the eyes of a series of clay votive offerings, which were specially made for me, were not painted at the potter’s house, but in the verandah of the traveller’s bungalow where I was staying.

The Tamil Kammālans are divided into three endogamous territorial groups, Pāndya, Sōzia (or Chōla), and Kongan. The Pāndyas live principally in the Madura and Tinnevelly districts, and the Sōzias in the Trichinopoly, Tanjore, Chingleput, North and South Arcot districts, and Madras. The Kongas are found chiefly in the Salem and Coimbatore districts. In some places, there are still further sub-divisions of territorial origin. Thus, the Pāndya Tattāns are divided into Karakattar, Vambanattar, Pennaikku-akkarayar (those on the other side of the Pennaiyar river), Munnūru-vīttukārar (those of the three hundred families), and so forth. They are further divided into exogamous septs, the names of which are derived from places, e.g., Perugumani, Musiri, Oryanādu, Thiruchendurai, and Kalagunādu.

The Kammālans are made up of five occupational sections, viz., Tattān (goldsmith), Kannān (brass-smith), Tac’chan (carpenter), Kal-Tac’chan (stone-mason), and Kollan or Karumān (blacksmith). The name Pānchāla, which is sometimes used by the Tamil as well as the Canarese artisan classes, has reference to the fivefold occupations. The various sections intermarry, but the goldsmiths have, especially in towns, ceased to intermarry with the blacksmiths. The Kammālans, claiming, as will be seen later on, to be Brāhmans, have adopted Brāhmanical gōtras, and the five sections have five gōtras called Visvagu, Janagha, Ahima, Janardana, and Ubhēndra, after certain Rishis (sages). Each of these gōtras, it is said, has twenty-five subordinate gōtras attached to it. The names of these, however, are not forthcoming, and indeed, except some individuals who act as priests for the Kammālans, few seem to have any knowledge of them. In their marriages the Kammālans closely imitate the Brāhmanical ceremonial, and the ceremonies last for three or five days according to the means of the parties. The parisam, or bride’s money, is paid, as among other non-Brāhmanical castes. Widows are allowed the use of ordinary jewelry and betel, which is not the case among Brāhmans, and they are not compelled to make the usual fasts, or observe the feasts commonly observed by Brāhmans.

The Kammālan caste is highly organised, and its organisation is one of its most interesting features. Each of the five divisions has at its head a Nāttāmaikkāran or headman, and a Kāryasthan, or chief executive officer, under him, who are elected by members of the particular division. Over them is the Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran (also known as Ainduvittu Periyathanakkāran or Anjijāti Nāttāmaikkāran), who is elected by lot by representatives chosen from among the five sub-divisions. Each of these chooses ten persons to represent it at the election. These ten again select one of their number, who is the local Nāttāmaikkāran, or one who is likely to become so. The five men thus selected meet on an appointed day, with the castemen, at the temple of the caste goddess Kāmākshi Amman. The names of the five men are written on five slips of paper, which, together with some blank slips, are thrown before the shrine of the goddess. A child, taken at random from the assembled crowd, is made to pick up the slips, and he whose name first turns up is proclaimed as Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran, and a big turban is tied on his head by the caste priest. This is called Urumā Kattaradu, and is symbolic of his having been appointed the general head of the caste. Lots are then drawn, to decide which of the remaining four shall be the Anjivīttu Kāryasthan of the newly-elected chief.

At the conclusion of the ceremony, betel leaf and areca nut are given first to the new officers, then to the local officers, and finally to the assembled spectators. With this, the installation ceremony, which is called pattam-kattaradu, comes to an end. The money for the expenses thereof is, if necessary, taken from the funds of the temple, but a special collection is generally made for the occasion, and is, it is said, responded to with alacrity. The Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran is theoretically invested with full powers over the caste, and all members thereof are expected to obey his orders. He is the final adjudicator of civil and matrimonial causes. The divisional heads have power to decide such causes, and they report their decisions to the Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran, who generally confirms them. If, for any reason, the parties concerned do not agree to abide by the decision, they are advised to take their cause to one of the established courts. The Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran has at times to nominate, and always the right to confirm or not, the selection of the divisional heads. In conjunction with the Kāryasthan and the local heads, he may appoint Nāttāmaikkārans and Kāryasthans to particular places, and delegate his powers to them.

This is done in places where the caste is represented in considerable numbers, as at Sholavandan and Vattalagūndu in the Madura district. In this connection, a quaint custom may be noted. The Pallans, who are known as “the sons of the caste” in villages of the Madura and Tinnevelly districts, are called together, and informed that a particular village is about to be converted into a local Anjivīttu Nāttānmai, and that they must possess a Nāttāmaikkāran and Kāryasthan for themselves. These are nominated in practice by the Pallans, and the nomination is confirmed by the Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran. From that day, they have a right to get new ploughs from the Kallans free of charge, and give them in return a portion of the produce of the land. The local Nāttāmaikkārans are practically under the control of the Kāryasthan of the Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran, and, as the phrase goes, they are “bound down to” the words of this official, who possesses great power and influence with the community.

The local officials may be removed from office by the Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran or his Kāryasthan, but this is rarely done, and only when, for any valid reason, the sub-divisions insist on it. The mode of resigning office is for the Nāttāmaikkāran or Kāryasthan to bring betel leaf and areca nut, lay them before the Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran, or his Kāryasthan, and prostrate himself in front of him. There is a tendency for the various offices to become hereditary, provided those succeeding to them are rich and respected by the community. The Anjivīttu Nāttāmaikkāran is entitled to the first betel at caste weddings, even outside his own jurisdiction. His powers are in striking contrast with those of the caste Guru, who resides in Tinnevelly, and occasionally travels northwards. He purifies, it is said, those who are charged with drinking intoxicating liquor, eating flesh, or crossing the sea, if such persons subject themselves to his jurisdiction. If they do not, he does not even exercise the power of excommunication, which he nominally possesses. He is not a Sanyāsi, but a Grihastha or householder. He marries his daughters to castemen, though he refrains from eating in their houses.

The dead are, as a rule, buried in a sitting posture, but, at the present day, cremation is sometimes resorted to. Death pollution, as among some other non-Brāhmanical castes, lasts for sixteen days. It is usual for a Pandāram to officiate at the death ceremonies. On the first day, the corpse is anointed with oil, and given a soap-nut bath. On the third day, five lingams are made with mud, of which four are placed in the four corners at the spot where the corpse was buried, and the fifth is placed in the centre. Food is distributed on the fifth day to Pandārams and the castemen. Srādh (annual death ceremony) is not as a rule performed, except in some of the larger towns.

The Kammālans profess the Saiva form of the Brāhman religion, and reverence greatly Pillaiyar, the favourite son of Siva. A few have come under the Lingāyat influence. The caste, however, has its own special goddess Kāmākshi Amma, who is commonly spoken of as Vriththi Daivam. She is worshipped by all the sub-divisions, and female children are frequently named after her. She is represented by the firepot and bellows-fire at which the castemen work, and presides over them. On all auspicious occasions, the first betel and dakshina (present of money) are set apart in her name, and sent to the pūjāri (priest) of the local temple dedicated to her. Oaths are taken in her name, and disputes affecting the caste are settled before her temple. There also elections to caste offices are held. The exact connection of the goddess Kāmākshi with the caste is not known. There is, however, a vague tradition that she was one of the virgins who committed suicide by throwing herself into a fire, and was in consequence deified. Various village goddesses (grāma dēvata) are also worshipped, and, though the Kammālans profess to be vegetarians, animal sacrifices are offered to them. Among these deities are the Saptha Kannimar or seven virgins, Kōchadē Periyāndavan, and Periya Nayanar. Those who worship the Saptha Kannimar are known by the name of Mādāvaguppu, or the division that worships the mothers.

Those who revere the other two deities mentioned are called Nādīkā Vamsathāl, or those descended from men who, through the seven virgins, attained eternal bliss. Kōchadē Periyāndavan is said to be a corruption of Or Jatē Periya Pāndyan, meaning the great Pāndya with the single lock. He is regarded as Vishnu, and Periya Nayanar is held to be a manifestation of Siva. The former is said to have been the person who invited the Tattāns (who called themselves Pāndya Tattāns) to settle in his kingdom. It is traditionally stated that they emigrated from the north, and settled in the Madura and Tinnevelly districts. An annual festival in honour of Kōchadē Periyāndavan is held in these districts, for the expenses in connection with which a subscription is raised among the five sub-divisions. The festival lasts over three days. On the first day, the image of the deified king is anointed with water, and a mixture of the juices of the mango, jāk (Artocarpus integrifolia), and plantain, called muppala pūjai. On the second day, rice is boiled, and offered to the god, and, on the last day, a healthy ram is sacrificed to him. This festival is said to be held, in order to secure the caste as a whole against evils that might overtake it. Tac’chans (carpenters) usually kill, or cut the ear of a ram or sheep, whenever they commence the woodwork of a new house, and smear the blood of the animal on a pillar or wall of the house.

The Kammālans claim to be descended from Visvakarma, the architect of the gods, and, in some places, claim to be superior to Brāhmans, calling the latter Gō-Brāhmans, and themselves Visva Brāhmans. Visvakarma is said to have had five sons, named Manu, Maya, Silpa, Tvashtra, and Daivagna. These five sons were the originators of the five crafts, which their descendants severally follow. Accordingly, some engage in smithy work, and are called Manus; others, in their turn, devote their attention to carpentry. These are named Mayas. Others again, who work at stone-carving, are known as Silpis. Those who do metal work are Tvashtras, and those who are engaged in making jewelry are known as Visvagnas or Daivagnas. According to one story of the origin of the Kammālans, they are the descendants of the issue of a Brāhman and a Bēri Chetti woman. Hence the proverb that the Kammālans and the Bēri Chettis are one. Another story, recorded in the Mackenzie manuscripts, which is current all over the Tamil country, is briefly as follows.

In the town of Māndāpuri, the Kammālans of the five divisions formerly lived closely united together. They were employed by all sorts of people, as there were no other artificers in the country, and charged very high rates for their wares. They feared and respected no king. This offended the kings of the country, who combined against them. As the fort in which the Kammālans concealed themselves, called Kāntakkōttai, was entirely constructed of loadstone, all the weapons were drawn away by it. The king then promised a big reward to anyone who would burn down the fort, and at length the Dēva-dāsīs (courtesans) of a temple undertook to do this, and took betel and nut in signification of their promise. The king built a fort for them opposite Kāntakkōttai, and they attracted the Kammālans by their singing, and had children by them. One of the Dēva-dāsīs at length succeeded in extracting from a young Kammālan the secret that, if the fort was surrounded with varaghu straw and set on fire, it would be destroyed. The king ordered that this should be done, and, in attempting to escape from the sudden conflagration, some of the Kammālans lost their lives. Others reached the ships, and escaped by sea, or were captured and put to death.

In consequence of this, artificers ceased to exist in the country. One pregnant Kammālan woman, however, took refuge in the house of a Bēri Chetti, and escaped decapitation by being passed off as his daughter. The country was sorely troubled owing to the want of artificers, and agriculture, manufactures, and weaving suffered a great deal. One of the kings wanted to know if any Kammālan escaped the general destruction, and sent round his kingdom a piece of coral possessing a tortuous aperture running through it, and a piece of thread. A big reward was promised to anyone who should succeed in passing the thread through the coral. At last, the boy born of the Kammālan woman in the Chetti’s house undertook to do it. He placed the coral over the mouth of an ant-hole, and, having steeped the thread in sugar, laid it down at some distance from the hole. The ants took the thread, and drew it through the coral. The king, being pleased with the boy, sent him presents, and gave him more work to do. This he performed with the assistance of his mother, and satisfied ]the king. The king, however, grew suspicious, and, having sent for the Chetti, enquired concerning the boy’s parentage. The Chetti thereon detailed the story of his birth.

The king provided him with the means for making ploughshares on a large scale, and got him married to the daughter of a Chetti, and made gifts of land for the maintenance of the couple. The Chetti woman bore him five sons, who followed the five branches of work now carried out by the Kammālan caste. The king gave them the title of Panchayudhattar, or those of the five kinds of weapons. They now intermarry with each other, and, as children of the Chetti caste, wear the sacred thread. The members of the caste who fled by sea are said to have gone to China, or, according to another version, to Chingaladvīpam, or Ceylon, where Kammālans are found at the present day. In connection with the above story, it may be noted that, though ordinarily two different castes do not live in the same house, yet Bēri Chettis and Kammālans so live together. There is a close connection between the Kammālans and Acharapākam Chettis, who are a section of the Bēri Chetti caste. Kammālans and Acharapākam Chettis interdine; both bury their dead in a sitting posture; and the tāli (marriage badge) used by both is alike in size and make, and unlike that used by the generality of the Bēri Chetti caste. The Acharapākam Chettis are known as Malighe Chettis, and are considered to be the descendants of those Bēri Chettis who brought up the Kammālan children, and intermarried with them. Even now, in the city of Madras, when the Bēri Chettis assemble for the transaction of caste business, the notice summoning the meeting excludes the Malighe Chettis, who can neither vote nor receive votes at elections, meetings, etc., of the Kandasāmi temple, which every other Bēri Chetti has a right to.

It may be noted that the Dēva-dāsīs, whose treachery is said to have led to the destruction of the Kammālan caste, were Kaikōlans by caste, and that their illegitimate children, like their progenitors, became weavers. The weavers of South India, according to old Tamil poems, were formerly included in the Kammiyan or Kammālan caste. Several inscriptions show that, as late as 1013 A.D., the Kammālans were treated as an inferior caste, and, in consequence, were confined to particular parts of villages. A later inscription gives an order of one of the Chōla kings that they should be permitted to blow conches, and beat drums at their weddings and funerals, wear sandals, and plaster their houses. “It is not difficult,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “to account for the low position held by the Kammālans, for it must be remembered that, in those early times, the military castes in India, as elsewhere, looked down upon all engaged in labour, whether skilled or otherwise.

With the decline of the military power, however, it was natural that a useful caste like the Kammālans should generally improve its position, and the reaction from their long oppression has led them to make the exaggerated claims described above, which are ridiculed by every other caste, high or low.” The claims here referred to are that they are descended from Visvakarma, the architect of the gods, and are Brāhmans. From a note by Mr. F. R. Hemingway, I gather that the friendship between the Muhammadans and Kammālans, who call each other māni (paternal uncle) originated in the fact that a holy Muhammadan, named Ibrahim Nabi, was brought up in the house of a Kammālan, because his father was afraid that he would be killed by a Hindu king named Namadūta, who had been advised by his soothsayers that he would thus avoid a disaster, which was about to befall his kingdom. The Kammālan gave his daughter to the father of Ibrahim in exchange. Another story (only told by Kammālans) is to the effect that the Kammālans were once living in a magnetic castle, called Kānda Kōttai, which could only be destroyed by burning it with varagu straw; and that the Musalmans captured it by sending Musalman prostitutes into the town, to wheedle the secret out of the Kammālans. The friendship, according to the story, sprang up because the Kammālans consorted with the Musalman women.”

The Kammālans belong to the left hand, as opposed to the right hand faction. The origin of this distinction of castes is lost in obscurity, but, according to one version, it arose out of a dispute between the Kammālans and Vellālas. The latter claimed the former as their Jātipillaigal or caste dependents, while the former claimed the latter as their own dependents. The fight grew so fierce that the Chōla king of Conjeeveram ranged these two castes and their followers on opposite sides, and enquired into their claims. The Kammālans, and those who sided with them, stood on the left of the king, and the Vellālas and their allies on the right. The king is said to have decided the case against the Kammālans, who then dispersed in different directions. According to another legend, a Kammālan who had two sons, one by a Balija woman, and the other by his Kammālan wife, was unjustly slain by a king of Conjeeveram, and was avenged by his two sons, who killed the king and divided his body.

The Kammālan son took his head and used it as a weighing pan, while the Balija son made a pedler’s carpet out of the skin, and threads out of the sinews for stringing bangles. A quarrel arose, because each thought the other had got the best of the division, and all the other castes joined in, and took the side of either the Kammālan or the Balija. Right and left hand dancing-girls, temples, and mandapams, are still in existence at Conjeeveram, and elsewhere in the Tamil country. Thus, at Tanjore, there are the Kammāla Tēvadiyāls, or dancing-girls. As the Kammālans belong to the left-hand section, dancing-girls of the right-hand section will not perform before them, or at their houses. Similarly, musicians of the right-hand section will not play in Kammālan houses. In olden days, Kammālans were not allowed to ride in palanquins through the streets of the right hands. If they did, a riot was the result. Such riots were common during the eighteenth century. Thus, Fryer refers to one of these which occurred at Masulipatam, when the contumacy of the Kamsalas (Telugu artisans) led to their being put down by the other castes with the aid of the Moors. The Kammālans call themselves Āchāri and Paththar, which are equivalent to the Brāhman titles Ācharya and Bhatta, and claim a knowledge of the Vēdas. Their own priests officiate at marriages, funerals, and on other ceremonial occasions. They wear the sacred thread, which they usually don on the Upakarmam day, though some observe the regular thread investiture ceremony. Most of them claim to be vegetarians. Non-Brāhmans do not treat them as Brāhmans, and do not salute them with the namaskāram (obeisance).

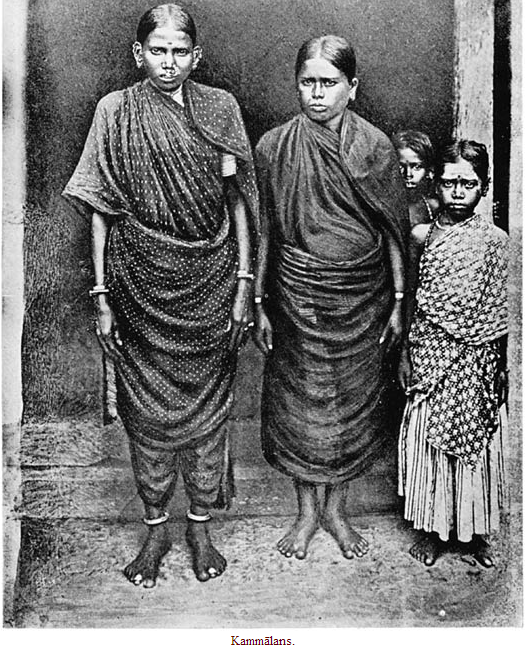

Their women, unlike those of other castes, throw the end of their body-cloth over the right shoulder, and are conspicuous by the nose ornament known as the nattu. In connection with the professional calling of the Kammālans, Surgeon-Major W. R. Cornish writes as follows. “The artisans, who are smiths or carpenters, usually bring up their children to the same pursuits. It might have been supposed that the hereditary influence in the course of generations would have tended to excellence in the several pursuits, but it has not been so. Ordinary native work in metal, stone, and wood, is coarse and rough, and the designs are of the stereotyped form. The improvement in handicraft work of late years has been entirely due to European influence. The constructors of railways have been great educators of artisans. The quality of stone-masonry, brick-work, carpentry, and smith-work has vastly improved within the last twenty years, and especially in districts where railway works have been in progress. The gold and silver smiths of Southern India are a numerous body. Their chief employment consists in setting and making native jewellery.

Some of their designs are ingenious, but here again the ordinary work for native customers is often noticeable for a want of finish, and, with the exception of a few articles made for the European markets, there is no evidence of progressive improvement in design or execution. That the native artists are capable of improvement as a class is evident from their skill and ingenuity in copying designs set before them, and from the excellent finish of their work under European supervision; but there must be a demand for highly finished work before the goldsmiths will have generally improved. The wearers of jewellery in India look more to the intrinsic value of an article, than to the excellence of the design or workmanship. So that there is very little encouragement for artistic display.” The collection of silver jewelry at the Madras Museum, which was made in connection with the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, London, 1886, bears testimony to the artistic skill of the silversmiths. Recently, Colonel Townshend, Superintendent of the Madras Gun Carriage Factory, has expressed his opinion that “good as the Bombay smiths are, the blacksmiths of Southern India are the best in Hindustan, and the pick of them run English smiths very close, not only in skill, but in speed of outturn.” Anyone who has seen the celebrated temples of Southern India, for example, the Madura and Tanjore temples, and the carving on temple cars, can form some idea of the skill of South Indian stone-masons and carpenters. The following note on idols and idol-makers is taken from a recent article.

“The idol-maker’s craft, like most of the other callings in this country, is a hereditary one, and a workman who has earned some reputation for himself, or has had an ancestor of renown, is a made man. The Sthapathi, as he is called in Sanskrit, claims high social rank among the representatives of the artisan castes. Of course he wears a heavy sacred thread, and affects Brāhman ways of living. He does not touch flesh, and liquor rarely passes down his throat, as he recognises that a clear eye and steady hand are the first essentials of success in his calling. There are two sorts of idols in every temple, mulavigrahas or stone idols which are fixed to the ground, and utsavavigrahas or metal idols used in processions. In the worst equipped pagoda there are at least a dozen idols of every variety. They do duty for generations, for, though they become black and begrimed with oil and ashes, they are rarely replaced, as age and dirt but add to their sanctity. But now and then they get desecrated for some reason, and fresh ones have to be installed in their stead; or it may be that extensions are made in the temple, and godlings in the Hindu Pantheon, not accommodated within its precincts till then, have to be carved and consecrated. It is on such occasions that the hands of the local Sthapathi are full of work, and his workshop is as busy as a bee-hive. In the larger temples, such as the one at Madura, the idols in which are to be counted by the score, there are Sthapathis on the establishment receiving fixed emoluments.

Despite the smallness of the annual salary, the office of temple Sthapathi is an eagerly coveted one, for, among other privileges, the fortunate individual enjoys that of having his workshop located in the temple premises, and thereby secures an advertisement that is not to be despised. Besides, he is not debarred from adding to his pecuniary resources by doing outside work when his hands are idle. Among stone images, the largest demand is for representations of Ganapati or Vignesvara (the elephant god), whose popularity extends throughout India. Every hamlet has at least one little temple devoted to his exclusive worship, and his shrines are found in the most unlikely places. Travellers who have had occasion to pass along the sandy roads of the Tanjore district must be familiar with the idols of the god of the protuberant paunch, which they pass every half mile or so, reposing under the shade of avenue trees with an air of self-satisfaction suffusing their elephantine features. Among other idols called into being for the purpose of wayside installation in Southern India, may be mentioned those of Vīran, the Madura godling, who requires offerings of liquor, Māriamma, the small-pox goddess, and the evil spirit Sangili Karappan. Representations are also carved of nāgas or serpents, and installed by the dozen round the village asvatha tree (Ficus religiosa).

Almost every week, the mail steamer to Rangoon takes a heavy consignment of stone and metal idols commissioned by the South Indian settlers in Burma for purposes of domestic and public worship. The usual posture of mulavigrahas is a standing one, the figure of Vishnu in the Srirangam temple, which represents the deity as lying down at full length, being an exception to this rule. The normal height is less than four feet, some idols, however, being of gigantic proportions. Considering the very crude material on which he works, and the primitive methods of stone-carving which he continues to favour, the expert craftsman achieves quite a surprising degree of smoothness and polish. It takes him several weeks of unremitting toil to produce a vigraha that absolutely satisfies his critical eye. I have seen him engaged for hours at a stretch on the trunk of Vignesvara or the matted tuft of a Rishi. The casting of utsavavigrahas involves a greater variety of process than the carving of stone figures. The substance usually employed is a compound of brass, copper and lead, small quantities of silver and gold being added, means permitting. The required figure is first moulded in some plastic substance, such as wax or tallow, and coated with a thin layer of soft wet clay, in which one or two openings are left. When the clay is dry, the figure is placed in a kiln, and the red-hot liquid metal is poured into the hollow created by the running out of the melted wax. The furnace is then extinguished, the metal left to cool and solidify, and the clay coating removed.

A crude approximation to the image required is thus obtained, which is improved upon with file and chisel, till the finished product is a far more artistic article than the figure that was enclosed within the clay. It is thus seen that every idol is made in one piece, but spare hands and feet are supplied, if desired. Whenever necessary, the Archaka (temple priest) conceals the limbs with cloth and flowers, and, inserting at the proper places little pieces of wood which are held in position by numerous bits of string, screws on the spare parts, so as to fit in with the posture that the idol is to assume during any particular procession.”

An association, called the Visvakarma Kulābhimana Sabha, was established in the city of Madras by the Kammālans in 1903. The objects thereof were the advancement of the community as a whole on intellectual and industrial lines, the provision of practical measures in guarding the interests, welfare and prospects of the community, and the improvement of the arts and sciences peculiar to them by opening industrial schools and workshops, etc. Of proverbs relating to the artisan classes, the following may be noted:— The goldsmith who has a thousand persons to answer. This in reference to the delay in finishing a job, owing to his taking more orders than he can accomplish in a given time.

The goldsmith knows what ornaments are of fine gold, i.e., knows who are the rich men of a place. It must either be with the goldsmith, or in the pot in which he melts gold, i.e., it will be found somewhere in the house. Said to one who is in search of something that cannot be found.

Goldsmiths put inferior gold into the refining-pot.

If, successful, pour it into a mould; if not, pour it into the melting pot. The Rev. H. Jensen explains that the goldsmith examines the gold after melting it. If it is free from dross, he pours it into the mould; if it is still impure, it goes back into the pot.

The goldsmith will steal a quarter of the gold of even his own mother.

Stolen gold may be either with the goldsmith, or in his fire-pot.

If the ear of the cow of a Kammālan is cut and examined, some wax will be found in it. It is said that the Kammālan is in the habit of substituting sealing-wax for gold, and thus cheating people. The proverb warns them not to accept even a cow from a Kammālan. Or, according to another explanation, a Kammālan made a figure of a cow, which was so lifelike that a Brāhman purchased it as a live animal with his hard-earned money, and, discovering his mistake, went mad. Since that time, people were warned to examine an animal offered for sale by Kammālans by cutting off its ears. A variant of the proverb is that, though you buy a Kammālan’s cow only after cutting its ears, he will have put red wax in its ears (so that, if they are cut into, they will look like red flesh).

What has a dog to do in a blacksmith’s shop? Said of a man who attempts to do work he is not fitted for.

When the blacksmith sees that the iron is soft, he will raise himself to the stroke.

Will the blacksmith be alarmed at the sound of a hammer?

When a child is born in a blacksmith’s family, sugar must be dealt out in the street of the dancing-girls. This has reference to the legendary relation of the Kammālans and Kaikōlans.

A blacksmith’s shop, and the place in which donkeys roll themselves, are alike.

The carpenters and blacksmiths are to be relegated, i.e., to the part of the village called the Kammālachēri.

What if the carpenter’s wife has become a widow? This would seem to refer to the former practice of widow remarriage. The carpenter wants (his wood) too long, and the blacksmith wants (his iron) too short, i.e., a carpenter can easily shorten a piece of wood, and a blacksmith can easily hammer out a piece of iron.

When a Kammālan buys cloth, the stuff he buys is so thin that it does not hide the hair on his legs.