Kuruba

(Created page with " {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article is an excerpt from<br/> ''' Castes and Tribes of Southern India ''' <br/> By '' Edgar Thurston,...") |

(→Kuruba) |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

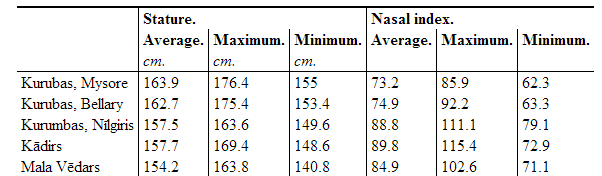

The language of the Kurumbas is a dialect of Canarese, and not of Tamil, as stated by Bishop Caldwell. It resembles the old Canarese.” Concerning the affinities of the Kurubas, Mr. Stuart states that “they are the modern representatives of the ancient Pallavas, who were once so powerful in Southern India. In the seventh century, the power of the Pallava kings seems to have been at its zenith, though very little trace of their greatness now remains; but, soon after this, the Kongu, Chōla, and Chālukya chiefs succeeded in winning several victories over them, and the final overthrow of the Kurumba sovereignty was effected by the Chōla King Adondai about the eighth century A.D., and the Kurumbas were scattered far and wide. Many fled to the hills, and, in the Nīlgiris and Wynād, in Coorg and Mysore, representatives of this ancient race are now found as wild and uncivilised tribes.” Let me call anthropometric evidence, and compare the Kurubas of Mysore and Bellary with the jungle Kurumbas of the Nīlgiris and the allied Kādirs and Mala Vēdars, by means of the two important physical characters, stature and nasal index. | The language of the Kurumbas is a dialect of Canarese, and not of Tamil, as stated by Bishop Caldwell. It resembles the old Canarese.” Concerning the affinities of the Kurubas, Mr. Stuart states that “they are the modern representatives of the ancient Pallavas, who were once so powerful in Southern India. In the seventh century, the power of the Pallava kings seems to have been at its zenith, though very little trace of their greatness now remains; but, soon after this, the Kongu, Chōla, and Chālukya chiefs succeeded in winning several victories over them, and the final overthrow of the Kurumba sovereignty was effected by the Chōla King Adondai about the eighth century A.D., and the Kurumbas were scattered far and wide. Many fled to the hills, and, in the Nīlgiris and Wynād, in Coorg and Mysore, representatives of this ancient race are now found as wild and uncivilised tribes.” Let me call anthropometric evidence, and compare the Kurubas of Mysore and Bellary with the jungle Kurumbas of the Nīlgiris and the allied Kādirs and Mala Vēdars, by means of the two important physical characters, stature and nasal index. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:364.png | |frame|500px]] |

In this table, the wide gap which separates the domesticated Kurubas of the Mysore Province and the adjacent Bellary district from the conspicuously platyrhine and short-statured Kurumbas and other jungle tribes, stands out prominently before any one who is accustomed to deal on a large scale with bodies and noses. And I confess that I like to regard the Kurumbas, Mala Vēdars, Kādirs, Paniyans, and other allied tribes of short stature with broad noses as the most archaic existing inhabitants of the south of the Indian peninsula, and as having dwelt in the jungles, unclothed, and living on roots, long before the seventh century. The question of the connection between Kurubas and Kurumbas is further discussed in the note on the latter tribe. | In this table, the wide gap which separates the domesticated Kurubas of the Mysore Province and the adjacent Bellary district from the conspicuously platyrhine and short-statured Kurumbas and other jungle tribes, stands out prominently before any one who is accustomed to deal on a large scale with bodies and noses. And I confess that I like to regard the Kurumbas, Mala Vēdars, Kādirs, Paniyans, and other allied tribes of short stature with broad noses as the most archaic existing inhabitants of the south of the Indian peninsula, and as having dwelt in the jungles, unclothed, and living on roots, long before the seventh century. The question of the connection between Kurubas and Kurumbas is further discussed in the note on the latter tribe. | ||

Latest revision as of 22:16, 3 April 2014

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

[edit] Kuruba

Though plucky in hunting bears and leopards, the Kurubas at Hospet were exceedingly fearful of myself and my methods, and were only partially ingratiated by an offer of a money prize at one of the wrestling combats, in which they delight, and of which I had a private exhibition. The wrestlers, some of whom were splendid specimens of muscularity, had, I noticed, the moustache clipped short, and hair clean shaved at the back of the head, so that there was none for the adversary to grip. One man, at the entreaties of an angry spouse, was made to offer up the silver coin, presented by me in return for the loan of his body for measurement, as bad money at the shrine of Udachallama, together with two annas of his own as a peace-offering to the goddess. The wives of two men (brothers), who came to me for measurement, were left sobbing in the village. One, at the last moment, refused to undergo the operation, on the principle that one should be taken, and the other left. A man was heard, at question time, to mutter “Why, when we are hardworking and poor, do we keep our hair, while this rich and lazy Sāhib has gone bald?” Another (I believe, the tame village lunatic) was more complimentary, and exclaimed “We natives are the betel leaf and nut. You, Sir, are the chunam (lime), which makes them perfect.”

Many of the Kurubas wear charms in the form of a string of black sheep’s wool, or thread tied round the arm or neck, sometimes with sacred ashes wrapped inside, as a vow to some minor deity, or a four anna piece to a superior deity. A priest wore a necklet of rudrāksha (Elæocarpus Ganitrus) beads, and a silver box, containing the material for making the sacred marks on the forehead, pendent from a loin string. His child wore a similar necklet, a copper ornament engraved with cabalistic devices, and silver plate bearing a figure of Hanumān, as all his other children had died, and a piece of pierced pottery from the burial-ground, to ward off whooping-cough, suspended round the neck. In colour-scale the Kurubas vary enormously, from very dark to light brown. The possessor of the fairest skin, and the greatest development of adipose tissue, was a sub-magistrate. At Hospet, many had bushy mutton-chop whiskers. Their garments consisted of a tight fitting pair of short drawers, white turban, and black kambli (blanket), which does duty as overcoat, umbrella, and sack for bringing in grass from the outlying country.

Some of the Kurubas are petty land-owners, and raise crops of cholam (Andropogon Sorghum), rice, Hibiscus cannabinus, etc. Others are owners of sheep, shepherds, weavers, cultivators, and stone-masons. The manufacture of coarse blankets for wearing apparel is, to a very large extent, carried on by the Kurubas. In connection with this industry, I may quote the following extracts from my “Monograph on the woollen fabric industry of the Madras Presidency” (1898). Bellary.—In the Bellary Manual (1872), it is stated that “cumblies are the great article of export, and the rugs made in the Kūdligi tāluk are in great demand, and are sent to all parts of the country. They are manufactured of various qualities, from the coarse elastic cumbly used in packing raw cotton, price about six annas, to a fine kind of blanket, price Rs. 6 to 8. In former times, a much finer fabric was manufactured from the wool of the lamb when six months old, and cumblies of this kind sold for Rs. 50 or Rs. 60. These are no longer made.” Coarse blankets are at present made in 193 villages, the weavers being mostly Kurubas, who obtain the wool locally, sun-dry it, and spin it into thread, which is treated with a watery paste of tamarind seeds. The weaving is carried out as in the case of an ordinary cotton cloth, the shuttle being a piece of wood hollowed out on one side. Inside the ruined Marātha fort at Sandūr dwells a colony of Kurubas, whose profession is blanket-weaving. The preliminary operations are performed by the women, and the weaving is carried out by the men, who sit, each in his own pit, while they pass the shuttle through the warp with repeated applications of tamarind paste from a pot at their side.

Kurnool.—Blankets are manufactured in 39 villages. Sheep’s wool is beaten and cleaned, and spun into yarn with hand spindles. In the case of the mutaka, or coarse cumblies used by the poorer classes, the thread used for the warp is well rubbed with a gruel made of tamarind seeds before being fitted up in the loom, which is generally in the open air. In the case of jadi, or cumblies of superior quality used as carpets, no gruel is used before weaving. But, when they are taken off the loom, the weavers spread them out tight on a country cot, pour boiling water over them, and rub them well with their hands, until the texture becomes thick and smooth.

Kistna.—Both carpets and blankets are made at Masulipatam, and blankets only, to a considerable extent, in the Gudivāda tāluk. The Tahsildar of Nuzvīd, in several villages of which tāluk the blanket-weaving industry is carried on, gives me the following note. The sheep, of which it is intended to shear the wool, are first bathed before shearing. If the wool is not all of the same colour, the several colours are picked out, and piled up separately. This being done, each separate pile is beaten, not as a whole, but bit by bit, with a light stick of finger thickness. Then the cleaning process is carried out, almost in the way adopted by cotton-spinners, but with a smaller bow. Then the wool is spun into yarn with the help of a thin short piece of stick, near the bottom of which a small flat, circular or square weight of wood or pot-stone (steatite) is attached, so as to match the force of the whirling given to the stick on the man’s thigh. After a quantity of yarn has been prepared, a paste is smeared over it, to stiffen it, so that it can be easily passed through the loom. The paste is prepared with kajagaddalu, or tamarind seeds, when the former is not available. Kajagaddalu is a weed with a bulbous root, sometimes as large as a water-melon. The root is boiled in water, and the thin coating which covers it removed while it is still hot. The root is then reduced to a pulp by beating in a mortar with frequent sprinkling of water. The pulp is mixed with water, to make it sticky, and applied to the yarn. Tamarind seeds are split in two, and soaked in water for several hours. The outer coating then becomes detached, and is removed. The seeds are beaten into a fine flour, and boiled until this acquires the necessary consistency. They are then made into a paste with water, and applied to the yarn.

Madura.—Coarse blankets are manufactured to a small extent by Kuruba women in twenty-two villages of the Mēlūr, Dindigul, and Palni tāluks.

In the province of Mysore, parts of Chitaldrūg and the town of Kolar are noted for the manufacture of a superior kind of blanket, of fine texture like homespun, by Kurubas. The wool is spun by the women. By one section of the Kurubas, called Sunnata or Vasa (new) only white blankets are said to be made. The personal names of Kurubas are derived from their gods, Basappa, Lingappa, Narasimha, Huliga, etc., with Ayya, Appa, or Anna as affixes. An educational officer tells me that, when conducting a primary examination, he came across a boy named Mondrolappa after Sir Thomas Munro, who still lives in the affections of the people.

“It has,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “been suggested that the name Kuruba is a derivative of the Canarese root kuru, sheep (cf. Tamil kori); but it has been objected to this that the Kurumbas were not originally a purely shepherd tribe, and it is contended that the particular kind of sheep called kori is so called because it is the sheep of the Kurumbas. Again, the ancient lexicographer of the Tamil language, Pingala Muni, defines Kurumban as Kurunila Mannar, or petty chieftains. But the most common derivation is from the Tamil kurumbu, wickedness, so that Kurumban means a wicked man. With this may be compared the derivation of Kallan from kalavu, theft, and the Kallans are now generally believed to have been closely connected with, if not identical with the original Kurumbas. On the other hand, the true derivation may be in the other direction, as in the case of the Sclavs.

The language of the Kurumbas is a dialect of Canarese, and not of Tamil, as stated by Bishop Caldwell. It resembles the old Canarese.” Concerning the affinities of the Kurubas, Mr. Stuart states that “they are the modern representatives of the ancient Pallavas, who were once so powerful in Southern India. In the seventh century, the power of the Pallava kings seems to have been at its zenith, though very little trace of their greatness now remains; but, soon after this, the Kongu, Chōla, and Chālukya chiefs succeeded in winning several victories over them, and the final overthrow of the Kurumba sovereignty was effected by the Chōla King Adondai about the eighth century A.D., and the Kurumbas were scattered far and wide. Many fled to the hills, and, in the Nīlgiris and Wynād, in Coorg and Mysore, representatives of this ancient race are now found as wild and uncivilised tribes.” Let me call anthropometric evidence, and compare the Kurubas of Mysore and Bellary with the jungle Kurumbas of the Nīlgiris and the allied Kādirs and Mala Vēdars, by means of the two important physical characters, stature and nasal index.

In this table, the wide gap which separates the domesticated Kurubas of the Mysore Province and the adjacent Bellary district from the conspicuously platyrhine and short-statured Kurumbas and other jungle tribes, stands out prominently before any one who is accustomed to deal on a large scale with bodies and noses. And I confess that I like to regard the Kurumbas, Mala Vēdars, Kādirs, Paniyans, and other allied tribes of short stature with broad noses as the most archaic existing inhabitants of the south of the Indian peninsula, and as having dwelt in the jungles, unclothed, and living on roots, long before the seventh century. The question of the connection between Kurubas and Kurumbas is further discussed in the note on the latter tribe.

The popular tradition as to the origin of the caste is as follows. Originally the Kurubas were Kāpus. Their ancestors were Masi Reddi and Nīlamma, who lived on the eastern ghāts by selling firewood, and had six sons. Taking pity on their poverty, Siva came begging to their house in the disguise of a Jangam, and gave Nīlamma some sacred ashes, while promising prosperity through the birth of another son, who was called Undala Padmanna. The family became prosperous through agriculture. But, unlike his six brothers, Undala Padmanna never went out to work in the fields. They accordingly contrived to get rid of him by asking him to set fire to some brushwood concealing a white-ant hill, in the hope that the snake within it would kill him. But, instead of a snake, an innumerable host of sheep appeared. Frightened at the sight of these strange black beasts, Undala Padmanna took to his heels. But Siva appeared, and told him that they were created for his livelihood, and that he should rear them, and live by their milk. He taught him how to milk the sheep and boil the milk, and sent him to a distant town, which was occupied by Rākshasas, to fetch fire.

There the giants were keeping in bondage a Brāhman girl, who fell in love with Undala Padmanna. They managed to escape from the clutches of the Rākshasas by arranging their beds over deep pits, which were dug for their destruction. To save her lover, the girl transformed him into a lizard. She then went with him to the place where his flock was, and Undala Padmanna married a girl of his own caste, and had male offspring by her as well as the Brāhman. At the marriage of these sons, a thread kankanam (bracelet) was tied to the wrist of the caste woman’s offspring, and a woollen kankanam to that of the Brāhman girl’s sons. The sons of the former were, therefore, called Atti (cotton) Kankanadavaru, and those of the latter Unni (woollen) Kankanadavaru. The latter are considered inferior, as they are of hybrid origin. A third sub-division is that of the Andē Kurubas, named after the small vessel (andē) used in milking goats. In a note on the Kurubas of Ālūr, Thikka, meaning a simpleton, is given as the name of an important division. It is noted in the Mysore Census Report, 1901, that the Kurubas have not taken kindly to education, and are by nature so simple that Kuruba has, in some places, become a byword for a simpleton. The Kurubas are also known as Hālu Mata, or milk caste, as they believe that they were created out of milk by Rēvana Siddēswara. In Hindustani they are called Dhangars, or rich people. Some, in spite of their poor dress and appearance, are well-to-do. At the Madras census, 1901, Kāvādiga, Kumpani, and Rāyarvamsam (Rāja’s clan) were returned by some members of the community. In Mysore, the Kurubas are said to be divided into Handē Kurubas and Kurubas proper, who have no intercourse with one another. The latter worship Bire Dēvaru, and are Saivites. According to another account, the Hālu Kurubas of Mysore have sub-divisions according to the day of the week, on which they offer pūja to their god, e.g., Aditya Vārada (Sunday), Brihaspati Vārada (Thursday), Sōma Vārada (Monday).

“The Kurubas,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “are again sub-divided into clans or gumpus, each having a headman or guru called a gaudu, who gives his name to the clan. And the clans are again sub-divided into gōtras or septs, which are mostly of totemistic origin, and retain their totemistic character to this day. The Arisana gōtram is particularly worthy of notice. The name means saffron (turmeric), and this was originally taboo; but, as this caused inconvenience, the korra grain has been substituted, although the old name of the sept was retained.” Exogamous septs.

• Agni, fire.

• Alige, drum.

• Andara, booth.

• Ānē, elephant.

• Arashina or Arisana, turmeric.

• Ārathi, wave offering.

• Ari, ebony.

• Ariya, noble.

• Āvu, snake.

• Bandi, cart.

• Banni (Prosopis spicigera).

• Basalē (Basella rubra).

• Batlu, cup.

• Belata (Feronia elephantum).

• Belli, silver.

• Bēlu (Ægle Marmelos).

• Bendē (Hibiscus esculentus).

• Benisē, flint.

• Bēvu or Bēvina (Melia Azadirachta).

• Bīnu, roll of woollen thread.

• Bola, bangle.

• Chandra, moon.

• Chēlu, scorpion.

• Chilla (Strychnos potatorum).

• Chinna or Sinnata, gold.

• Dēva, a tree.

• Emmē, buffalo.

• Gāli, devil.

• Gauda, headman.

• Gulimi, pick-axe.

• Hālu, milk.

• Hatti, hut.

• Honnungara, gold ring. • Ibābire, tortoise.

• Irula, darkness.

• Iruvu, black ant.

• Jelakuppa, a fish.

• Jīrige, cummin.

• Jīvala, an insect.

• Kalle, bengal gram.

• Kanchu, bell-metal.

• Kavada, coloured border of a cloth.

• Kombu, stick.

• Kori, blanket.

• Mānā, measure.

• Malli, jasmine.

• Menusu, pepper.

• Minchu, metal toe-ring.

• Mīse, moustache.

• Mugga, loom.

• Muttu, pearl.

• Nāli, bamboo tube.

• Nāyi, dog.

• Othu, goat.

• Putta, ant-hill; snake hole.

• Ratna, precious stones.

• Sāmanti or Sāvanti (Chrysanthemum).

• Sāmē (millet: Panicum miliare).

• Samudra, ocean.

• Sankhu, conch-shell.

• Sarige, lace.

• Sūrya, sun.

• Thuppa, clarified butter.

• Turaka, Muhammadan.

• Ungara, ring.

• Uppiri, earth-salt.

The titles of members of the caste are Gauda or Heggade, and the more prosperous go by the name of Kaudikiaru, a corruption of Gaudikiaru. Many, at the present day, have adopted the title Nāyakkan. Some are called Gorava Vāndlu. According to Mr. Stuart, “each community of Kurubas, residing in a group of villages, has a headman or Gaudu. He acts the part of pūjari or priest in all their ceremonies, presides over their tribal meetings, and settles disputes. He is paid four annas, or, as they call it, one rūka per house per annum. He is a strict vegetarian, and will not eat with other Kurubas.” The headman or guru of the caste in Bellary goes by the name of Rēvana Siddēswara, and he wears the lingam, and follows the Lingāyat creed. Sometimes he dines with his people, and, on these occasions, new cooking pots must be used. He exercises the power of inflicting fines, excommunicating those who have had illicit intercourse with Bōyas, Muhammadans, and others, etc.

The Kurubas in Bellary and Anantapūr are said to pay three pies to their guru for every blanket which they sell. The name of the tribal headman at Ālur is Kattaiyintivādu, i.e., shed with a pial or raised verandah in front of it. Among both Kurubas and Bēdars, a special building, built by public subscription, and called the katta-illu or chāvadi, is set apart for council meetings, at which tribal affairs are discussed and decided. When a girl reaches puberty, she is kept in a corner of the house for eight days. On the ninth day she bathes, and food is taken to her by an old woman of the house. Kuruba women are invited to be present in the evening. The girl, covered with a blanket, is seated on a raised place. Those assembled throw rice over her feet, knees, shoulders, and head, and into her lap. Coloured turmeric and lime water is then waved three or five times round her, and rāvikes (body-cloths) are presented to her.

The following account of the marriage ceremonial was recorded in Western Bellary. When a marriage has been settled between the parents of the young people, visits are exchanged by the two families. On a fixed day, the contracting couple sit on a blanket at the bride’s house, and five women throw rice over five parts of the body as at the menstrual ceremony. Betel leaves and areca-nuts are placed before them, of which the first portion is set apart for the god Bīrappa, the second for the Gauda, another for the house god, and so on up to the tenth. A general distribution then takes place The ceremony, which is called sākshi vilya or witness betel-leaf, is brought to a conclusion by waving in front of the couple a brass vessel, over the mouth of which five betel leaves and a ball of ashes are placed.

They then prostrate themselves before the guru. For the marriage ceremony, the services of the guru, a Jangam, or a Brāhman priest, are called into requisition. Early on the wedding morning, the bridal couple are anointed and washed. A space, called the irāni square, is marked out by placing at the four corners a pot filled with water. Round each pot a cotton thread is wound five times. Similar thread is also tied to the milk-post of the marriage pandal (booth), which is made of pīpal (Ficus religiosa) wood. Within the square a pestle, painted with red and white stripes, is placed, on which the bride and bridegroom, with two young girls, seat themselves. Rice is thrown over them, and they are anointed and washed. To each a new cloth is given, in which they dress themselves, and the wrist-thread (kankanam) is tied on all four. Presents are given by relations, and ārathi (red water) is waved round them. The bridegroom is decorated with a bāshingam (chaplet of flowers), and taken on a bull to a Hanumān shrine along with his best man. Cocoanuts, camphor, and betel are given to the priest as an offering to the god. According to another account, both bride and bridegroom go to the shrine, where a matron ties on their foreheads chaplets of flowers, pearls, etc.

At the marriage house a dais has been erected close to the milk-post, and covered with a blanket, on which a mill-stone and basket filled with cholum (Andropogon Sorghum) are placed. The bridegroom, standing with a foot on the stone and the bride with a foot on the basket, the gold tāli, after it has been touched by five married women, is tied round the bride’s neck by the officiating priest, while those assembled throw rice over the happy pair, and bless them. According to another version, a bed-sheet is interposed as a screen, so that the bride and bridegroom cannot see each other. On the three following days, the newly-married couple sit on the blanket, and rice is thrown over them. In Western Bellary, the bridegroom, on the third day, carries the bride on his waist to Hanumān temple, where married women throw rice over them. On the fifth morning, they are once more anointed and washed within the irāni square, and, towards evening, the bride’s father hands her over to her husband, saying “She was till this time a member of my sept and house. Now I hand her over to your sept and house.” On the night of the sixth day, a ceremony called booma idothu (food placing) is performed. A large metal vessel (gangālam) is filled with rice, ghī (clarified butter), curds, and sugar. Round this some of the relations of the bride and bridegroom sit, and finish off the food. The number of those, who partake thereof must be an odd one, and they must eat the food as quickly as possible. If anything goes wrong with them, while eating or afterwards, it is regarded as an omen of impending misfortune. Some even consider it as an indication of the bad character of the bride.

Concerning the marriage ceremony of the Kurubas of North Arcot, Mr. Stuart writes as follows. “As a preliminary to the marriage, the bridegroom’s father observes certain marks or curls on the head of the proposed bride. Some of these are believed to forebode prosperity, and others only misery to the family, into which the girl enters. They are, therefore, very cautious in selecting only such girls as possess curls (suli) of good fortune. This curious custom, obtaining among this primitive tribe, is observed by others only in the case of the purchase of cows, bulls, and horses. One of the good curls is the bāshingam found on the forehead; and the bad ones are the pēyanākallu at the back of the head, and the edirsuli near the right temple. But widowers seeking for wives are not generally particular in this respect.

[As bad curls are supposed to cause the death of the man who is their possessor, she is, I am informed, married to a widower.] The marriage is celebrated in the bridegroom’s house, and, if the bride belongs to a different village, she is escorted to that of the bridegroom, and is made to wait in a particular spot outside it, selected for the occasion. On the first day of the marriage, pūrna kumbam, a small decorated vessel containing milk or ghī, with a two-anna piece and a cocoanut placed on the betel leaf spread over the mouth of it, is taken by the bridegroom’s relations to meet the bride’s party. Therethe distribution of pān supāri takes place, and both parties return to the village. Meanwhile, the marriage booth is erected, and twelve twigs of nāval (Eugenia Jambolana) are tied to the twelve pillars, the central or milk post, under which the bridal pair sit, being smeared with turmeric, and a yellow thread being tied thereto.

At an auspicious hour of the third day, the couple are made to sit in the booth, the bridegroom facing the east, and the bride facing west. On a blanket spread near the kumbam, 2½ measures of rice, a tāli or bottu, one cocoanut, betel leaf and camphor are placed. The Gaudu places a ball of vibhūti (sacred ashes) thereon, breaks a cocoanut, and worships the kumbam, while camphor is burnt. The Gaudu next takes the tāli, blesses it, and gives it to the bridegroom, who ties it round the bride’s neck. The Gaudu then, throwing rice on the heads of the pair, recites a song, in which the names of various people are mentioned, and concluding ‘Oh! happy girl; Oh! prosperous girl; Basava has come; remove your veil.’ The girl then removes her veil, and the men and women assembled throw rice on the heads of the bridal pair. The ends of their garments are then tied together, and two girls and three boys are made to eat out of the plates placed before the married couple.

A feast to all their relations completes the ceremony. The Gaudu receives 2½ measures of rice, five handfuls of nuts and betel leaf, and twelve saffrons (pieces of turmeric) as his fee. Even though the girl has attained puberty, the nuptial ceremony is not coincident with the wedding, but is celebrated a few months later.” In like manner, among the Kammas, Gangimakkulu, and other classes, consummation does not take place until three months after the marriage ceremony, as it is considered unlucky to have three heads of a family in a household during the first year of marriage. By the delay, the birth of a child should take place only in the second year, so that, during the first year, there will be only two heads, husband and wife. At a marriage among the Kurubas of the Madura district, a chicken is waved in front of the contracting couple, to avert the evil eye. The maternal uncle’s consent to a marriage is necessary, and, at the wedding, he leads the bride to the pandal. A Kuruba may, I am informed, marry two sisters, either on the death of one of them, or if his first wife has no issue, or suffers from an incurable disease. Some twenty years ago, when an unmarried Kuruba girl was taken to a temple, to be initiated as a Basavi (dedicated prostitute), th caste men prosecuted the father as a protest against the practice.

In the North Arcot district, according to Mr. Stuart, “the mother and child remain in a separate hut for the first ten days after delivery. On the eleventh day, all the Kuruba females of the village bring each a pot of hot water, and bathe the mother and child. Betel and nuts are distributed, and all the people of the village eat in the mother’s house. On the next market-day, her husband, with some of his male friends, goes to a neighbouring market, and consults with a Korava or Yerukala what name is to be given to the child, and the name he mentions is then given to it.” In a case which came before the police in the Bellary district in 1907, a woman complained that her infant child had been taken away, and concealed in the house of another woman, who was pregnant. The explanation of the abduction was that there is a belief that, if a pregnant woman keeps a baby in her bed, she will have no difficulty at the time of delivery. Remarriage of widows is permitted. The ceremony is performed in a temple or dark room, and the tāli is tied by a widow, a woman dedicated to the deity, or a Dāsayya (mendicant) of their own caste. According to another account, a widow is not allowed to wear a tāli, but is presented with a cloth. Hence widow marriage is called Sirē Udiki. Children of widows are married into families in which no widow remarriage has taken place, and are treated like ordinary members of the community.

In Western Bellary I gathered that the dead are buried, those who have been married with the face upwards, others with the face downwards. The grave is dug north and south, and the head is placed to the south. Earth is thrown into the grave by relations before it is filled in. A mound is raised over it, and three stones are set up, over the head, navel, and feet. The eldest son of the deceased places on his left shoulder a pot filled with water, in the bottom of which three small holes are made, through which the water escapes. Proceeding from the spot beneath which the head rests, he walks round the grave, and then drops the pot so that it falls on the mound, and goes home without looking back. This ceremony is a very important one with both Kurubas and Bēdars. In the absence of a direct heir, he who carries the pot claims the property of the deceased, and is considered to be the inheritor thereof. For the propitiation of ancestors, cooked rice and sweetmeats, with a new turban and cloth or petticoat, according to the sex of the deceased, are offered up. Ancestors who died childless, unless they left property, do not receive homage. It is noted, in the Bellary Gazetteer, that “an unusual rite is in some cases observed after deaths, a pot of water being worshipped in the house on the eleventh day after the funeral, and taken the next morning and emptied in some lonely place. The ceremony is named the calling back of the dead, but its real significance is not clear.”

Of the death ceremonies in the North Arcot district, Mr. Stuart writes that “the son, or, in his absence, a near relative goes round the grave three times, carrying a pot of water, in which he makes a hole at each round. On the third round he throws down the pot, and returns home straight, without turning his face towards the direction of the grave. For three days, the four carriers of the bier are not admitted into their houses, but they are fed at the cost of the deceased’s heir. On the the third day, cooked rice, a fowl and water are taken to the burial-ground, and placed near the grave, to be eaten by the spirit of the dead. The son, and all his relations, return home, beating on their mouths. Pollution is observed for ten days, and, on the eleventh day, sheep and fowls are killed, and a grand feast is given to the Kurumbas of the village. Before the feast commences, a leaf containing food is placed in a corner of the house, and worshipped. This is removed on the next morning, and placed over the roof, to be eaten by crows. If the deceased be a male, the glass bangles worn by his wife on her right arm are broken on the same day.”

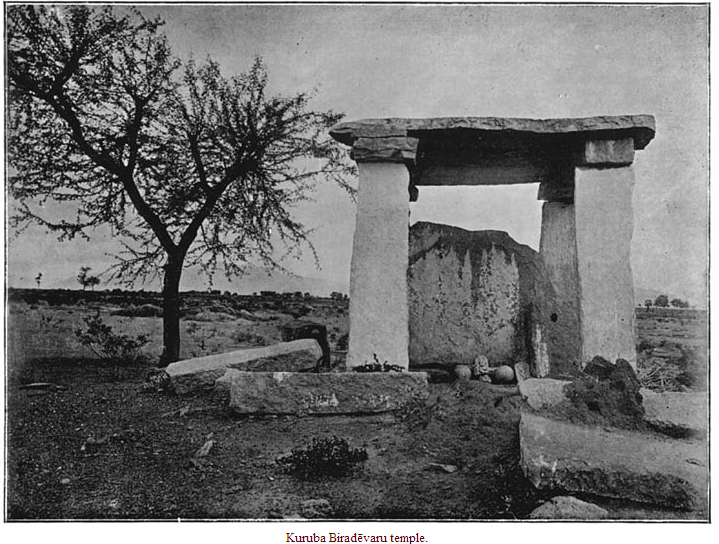

The patron saint of the Kurubas is Bīrappa or Bīradēvaru, and they will not ride on horses or ponies, as these are the vehicles of the god. But they worship, in addition, various minor deities, e.g., Uligamma, Mallappa, Anthargattamma, Kencharāya, and have their house gods, who are worshipped either by a house or by an entire exogamous sept. In some places, Māriamma and Sunkulamma are worshipped on Tuesday and Friday, and the sheep and other offerings are the perquisite of Bōyas, Mālas, and Mādigas. Some families of Kuruba Dāsaris reverence a goddess called Hombālamma, who is worshipped secretly by a pūjāri (priest) at dead of night. Everything used in connection with the rite is buried or otherwise disposed of before morning. The Kurubas show reverence for the jammi tree (Prosopis spicigera) and ashwatham (Ficus religiosa) by not cutting them. It was noticed by Mr. F. Fawcett that, at the temples of the village goddesses Wannathamma and Durgamma in the Bellary district, an old Kuruba woman performs the daily worship. In the mantapam of the temple at Lēpākshi, in the Anantapur district, “is the sculptured figure of a man leaning his chin upon his hands, which is said to represent a Kuruba who once acted as mediator between the builder of the temple and his workmen in a dispute about wages. The image is still bathed in oil, and worshipped by the local Kurubas, who are proud of the important part played by their caste-man.” In Mysore, the Kurubas are said to worship a box, which they believe contains the wearing apparel of Krishna under the name of Junjappa. One of the goddesses worshipped by the Kurubas is named Kēlu Dēvaru or Manē Hennu Dēvaru, the pot or household deity. She is worshipped annually at the Dasara festival, and, on occasions of marriage, just before the tāli is tied. The pot is made by a Kumbāra (potter), who is well paid for his work. During its manufacture, he has to take only one meal daily, and to avoid pollution of all kinds. The clay should be kneaded with the hands, and wetted with milk, milk of tender cocoanuts, and water. When at work on it, the potter should close his mouth with a bandage, so that his breath may not defile the pot. The Kurubas who are settled in the Madura district reverence Vīra Lakkamma (Lakshmi) as their family deity, and an interesting feature in connection with the worship of their goddess is that cocoanuts are broken on the head of a special Kuruba, who becomes possessed by the deity.

The Kurubas are ancestor worshippers, and many of them have in their possession golden discs called hithāradha tāli, with the figures of one or more human beings stamped on them. The discs are made by Akasāles (goldsmiths), who stamp them from steel dies. They are either kept in the house, or worn round the neck by women. If the deceased was a celebrity in the community, a large plate is substituted for a disc. Concerning the religion of the Kurubas, Mr. Francis writes as follows. “The most striking point about the caste is its strong leaning towards the Lingāyat faith. Almost everywhere, Jangams are called in as priests, and allegiance to the Lingāyat maths (religious institutions) is acknowledged, and in places (Kāmalāpuram for example), the ceremonies at weddings and funerals have been greatly modified in the direction of the Lingāyat pattern.” “In the North Arcot district, the Gaudu is entrusted with the custody of a golden image representing the hero of the clan, and keeps it carefully in a small box filled with turmeric powder.

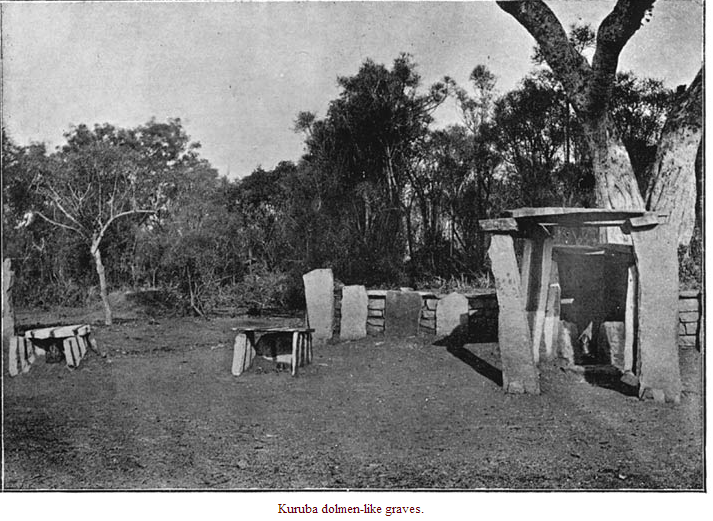

There are also some images set up in temples built for the purpose. Once a year, several neighbouring clans assemble at one of their bigger temples, which is lighted with ghī, and, placing their images in a row, offer to them flowers, cocoanuts, milk, etc., but they do not slay any victim. On the last day of their festival, the Kurumbas take a bath, worship a bull, and break cocoanuts upon the heads of pūjāris who have an hereditary right to this distinction, and upon the head of the sacred bull. Some Kurumbas do not adopt this apparently inhuman practice. A pūjāri or priest, supposed to have some supernatural power, officiates, and begins by breaking a few nuts on the heads of those nearest to him, and then the rest go on, the fragments belonging by right to those whose skulls have cracked them, and who value the pieces as sacred morsels of food. For a month before this ceremony, all the people have taken no meat, and for three days the pūjāris have lived on fruits and milk alone. At the feast, therefore, all indulge in rather immoderate eating, but drink no liquor, calling excitedly upon their particular god to grant them a prosperous year. The temples of this caste are usually rather extensive, but rude, low structures, resembling an enclosed mantapam supported upon rough stone pillars, with a small inner shrine, where the idols are placed during festival time. A wall of stone encloses a considerable space round the temple, and this is covered with small structures formed of four flat stones, three being the walls, and the fourth the roof. The stone facing the open side has a figure sculptured upon it, representing the deceased Gaudu, or pūjāri, to whom it is dedicated. For each person of rank one of these monuments is constructed, and here periodically, and always during the annual feasts, pūja is made not only to the spirits of the deceased chiefs, but also to those of all who have died in the clan. It seems impossible not to connect this with those strange structures called by the natives Pāndava’s temples. They are numerous where the Kurumbas are now found, and are known to have been raised over the dead. Though the Kurumbas bury, they do not now raise their monuments over the resting place of the corpse. Nor can they build them upon anything approaching to the gigantic scale of the ancient kistvaen or dolmen.”

It was noted by a correspondent of the Indian Antiquary that, in the Kaladgi ‘district,’ he “came across the tomb of a Kuruba only four years old. It was a complete miniature dolmen about eighteen inches every way, composed of four stones, one at each side, one at the rear, and a cap-stone. The interior was occupied by two round stones about the size of a man’s fist, painted red, the deceased resting in his mother earth below.” In the open country near Kadūr in Mysore, is a shrine of Bīradēvaru, which consists of four stone pillars several feet in height surmounted by flat slabs as a cap-stone, within which the deity is represented by round stones, and stones with snakes carved on them are deposited. Within the Kuruba quarter of the town, the shrine of Anthargattamma is a regular dolmen beneath a margosa (Melia Azadirachta) tree, in which the goddess is represented by rounded stones imbedded in a mound of earth. Just outside the same town, close to a pīpal tree (Ficus religiosa) are two smaller dolmen-like structures containing stones representing two Kuruba Dāsaris, one a centenarian, who are buried there.

“The village of Maliar, in the Hadagalli tāluk of the Bellary district, contains a Siva temple, which is famous throughout the district for an annual festival held there in the month of February. This festival has now dwindled more or less into a cattle fair. But the fame of the temple continues as regards the kāranika, which is a cryptic sentence uttered by a priest, containing a prophecy of the prospect of the agricultural season of the ensuing year. The pūjāri of the temple is a Kuruba. The feast in the temple lasts for ten days. On the last day of the feast, the god Siva is represented as returning victorious from the battlefield after having slain Malla with a huge bow. He is met half-way from the field of battle by the goddess. The huge wooden bow is brought, and placed on end before the god. The Kuruba priest climbs up the bow as it is held up by two assistants, and then gets on the shoulders of these men. In this posture he stands rapt in silence for a few minutes, looking in several directions.

He then begins to quake and quiver from head to foot. This is the sign of the [155]spirit of the Siva god possessing him—the sign of the divine afflatus upon him. A solemn silence holds the assembly, for the time of the kāranika has approached. The shivering Kuruba utters a cryptic sentence, such as Ākāsakkē sidlu bodiyuttu, or thunder struck the sky. This is at once copied down, and interpreted as a prophecy that there will be much rain in the year to come. Thus every year, in the month of February, the kāranika of Mailar is uttered and copied, and kept by all in the district as a prophecy. This kāranika prognostication is also pronounced now at the Mallari temple in the Dharwar district, at Nerakini in the Ālūr tāluk, and at Mailar Lingappa in the Harapanahalli tāluk.”

The rule of inheritance among the Kurubas is said to differ very little from that current among Hindus, but the daughters, if the deceased has no son, share equally with the agnates. They belong to the right-hand faction, and have the privilege of passing through the main bazārs in processions. Some Mudalis and ‘Naidus’ are said to have no objection to eat, drink, and smoke with Kurubas. Gollas and some inferior flesh-eating Kāpus will also do so.