Rohtak District, 1908

(Created page with " {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article has been extracted from <br/> THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908.<br/> OXFORD, AT THE CLA...") |

Latest revision as of 19:59, 14 June 2014

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

[edit] Physical aspects

District in the Delhi Division of the Punjab, lying between 28 21' and 29 if N. and 76 13' and 76 58' E., on the borders of Rajputana, in the high level plain that separates the waters of the Jumna and Sutlej, with an area of 1,797 square miles. The eastern part falls within the borders of the tract formerly known as Hariana. In its midst lies part of the small State of Dujana. It is bounded on the north by the Jind nizamat of Jind State, and by Karnal District; on the east by Delhi, and on the south-east by Gurgaon ; on the south by Pataudi State and the Rewari tahsil of Gurgaon } on the south-west by territory belonging to the Nawab of Dujana ; and on the west by the Dadn ntzdmat of Jind and by Hissar District. Although there is no grand sceneiy in Rohtak, the canals with their belts of trees, the lines of sandhills, and in the south the torrents, the depressions which are flooded after heavy rain and a few small rocky hills give the Dis- trict more diversified features than are generally met with in the plains of the Punjab. The eastern border lies low on the level of the Jumna Canal and the Najafgarh swamp.

A few miles west the surface rises gradually to a level plateau, which, speaking roughly, stretches as far as the town of Rohtak, and is enclosed by parallel rows of sandhills running north and south. Beyond the western line of sandhills the surface rises again till it ends on the Hissai border in a third high ridge. The eastern line runs, with here and there an interval, down the east side of the District, and rises to some height in the Jhajjar tahsil. South-west of this ridge the country becomes more undulating, and the soil lighter. The south-eastern corner of the District is crossed by two small streams or torrents, the Sahibi and Indon ; these flow circuitously, throwing oft a network of branches and collecting here and there after heavy rain v&jhih of considerable size, and finally fall into the Najafgaih swamp With the exception of a few small outliers of Alwar quartzite be- longing to the Delhi system, there is nothing of geological interest in the District, which is almost entirely of alluvial formation.

The District forms an arm from the Upper Gangetic plain between the Cential Punjab and the desert Trees, except where naturalized or planted, are rare, but the nimbar (Acacia kucophloea) is a conspicuous exception. Mango groves are frequent in the north-east ; and along canals and roadsides other sub-tropical species have been planted successfully. The ber (Zhyphus Jujubd) is common, and is often planted.

Game, including wild hog, antelope, ' ravine deer ' (Indian gazelle), nilgai, and hare, is plentiful. Peafowl, partridge, and quail are to be met with throughout the year , and during the cold season sand-grouse, wild geese, bustards, and flamingoes. Wolves are still common, and a stray leopard is occasionally killed. The villages by the canal are overrun by monkeys.

The climate is not inaptly described in the Memoirs of George Thomas as ' in general salubrious, though when the sandy and desert country lying to the westward becomes heated, it is inimical to a European constitution.' In April, May, and June the hot winds blow steadily all day from the west, bringing up constant sandstorms fiom the Rajputana deseit , at the close of the year frosts are common, and strong gales prevail in Februaiy and March.

The average rainfall varies from 19 inches at Jhajjar to 21 at Rohtak Of the rainfall at the latter place, 18 inches fall in the summer months and 3 m the winter The greatest fall recorded during the years 1885-1902 was 41 inches at Jhajjar in 1885-6, and the least 8 inches at Rohtak in 1901-2.

[edit] History

The District belongs for the most part to the tract of HARIANA, and its early history will be found in the articles on that region and on the towns of ROHTAK, MAHAM, and JHAJJAR. It appears Histor to have come at an early date under the control of the Delhi kings, and in 1355 Fnoz Shah dug a canal from the Sutlej as far as Jhajjar. Under Akbar the present District lay within the Siibah of Delhi and the sarkars of Delhi and Hissar-Firoza. In 1643 the Rohtak canal is said to have been begun by Nawab All Khan, who attempted to divert water from the old canal of Firoz Shah. On the decay of the Delhi empire the District with the rest of Hariana was granted to the minister Rukn-ud-dm in 1718 and was in 1732 trans- ferred by him to the Nawabs of Farrukhnagar in GURGAON Faujdar Khan, Nawab of Farrukhnagar, who seems to have succeeded to the territories of Hissar on the death of Shahdad Khan in 1738, handed down to his son, Nawab Kamgar Khan, a dominion which embraced the present Districts of Hissar and Rohtak, besides part of Gurgaon and a considerable tract subsequently annexed by the chiefs of Jind and Patiala. Hissar and the north were during this time perpetually overrun by the Sikhs, in spite of the combined efforts of the Bhattis and the imperial forces, but Rohtak and Gurgaon appear to have remained with Kamgar Khan till his death in 1760.

His son, Musa Khan, was expelled from Farrukhnagar by Suraj Mal 3 the Jat ruler of Bharatpur , and the Jats held Jhajjar, Badh, and Farrukhnagar till 1771. In that year Musa Khan recovered Farrukhnagar, but he never regained a footing in Rohtak District. In 1772 Najaf Khan came into power at Delhi, and till his death in 1782 some order was main- tained. Bahadurgarh, granted in 1754 to Bahadur Khan, Baloch, was held by his son and grandson ; Jhajjar was in the hands of Walter Reinhardt, the husband of Begam Sumru of Sardhana ; and Gohana, Maham, Rohtak, and Kharkhauda were also held by nominees of Najaf Khan. The Marathas returned m 1785, but could do little to repel the Sikh invasion, and from 1785 to 1803 the north of the District was occupied by the Raja of Jind, while the south and west were precariously held by the Marathas, who were defied by the strong Jat villages and constantly attacked by the Sikhs.

Meanwhile the military adventurer George Thomas had carved out a principality in Hariana, which included Maham, Ben, and Jhajjar in the present District., his head-quarters were at Hansi in the District of Hissar, and at Georgegarh near Jhajjar he had built a small outlying fort. In r So i, however, the Marathab made common cause with the Sikhs and Rajputs against him, and under the French commander, Louis Bourqum, defeated him at Georgegarh, and succeeded in ousting him from his dominions. In 1803, by the conquests of Lord Lake, the whole country up to the Sutlej and the Siwahks passed to the British Government.

Under Lord Lake's arrangements, the northern parganas of Rohtak were held by the Sikh chiefs of Jind and Kaithal, while the south was granted to the Nawab of Jhajjar, the west to his brother, the Nawab of Dadrl and Bahadurgarh, and the central tract to the Nawab of Dujana The latter, however, was unable to maintain order in his portion of the territories thus assigned, and the frequent incursions of Sikh and Bhatti marauders compelled the dispatch of a British officer in 1810 to bring the region into better organization. The few parganas thus subjected to British rule formed the nucleus of the present District. Other fringes of territory escheated on the deaths of the Kaithal Raja in 1818 and the chief of Jind in 1820. In the last-named year, Hissar and Sirsa weie separated from Rohtak ; and in 1824 the District was brought into nearly its present shape by the District of Panipat (now Karnal) being made a separate charge.

Up to 1832 Rohtak was administered by a Political Agent under the Resident at Delhi , but it was then brought under the Regulations, and included in the North-Western Provinces. On the outbreak of the Mutiny in 1857, Rohtak was for a time completely lost to the British Government. The Muhammadan tribes, uniting with their brethren in Gurgaon and Hissai, began a general predatory movement under the Nawabs of Farrukhnagar, Jhajjar, and Bahadurgarh, and the Bhatti chieftains of Sirsa and Hissar. They attacked and plundered the civil station at Rohtak, destroying every record of administration But before the fall of Delhi, a force of Punjab levies was brought across the Sutlej, and order was restored with little difficulty.

The rebel Nawabs of Jhajjar and Bahadurgarh were captured and tried. The former was executed at Delhi, while his neighbour and relative escaped with a sentence of exile to Lahore Their estates were confiscated, part of them being temporarily included in a new District of Jhajjar, while other portions were assigned to the Rajas of Jind, Patiala, and Nabha as rewards for their services during the Mutiny. Rohtak Dis- trict was transferred to the Punjab Government , and in 1860 Jhajjar was broken up, part of it being added to the territory of the loyal Raj as, and the remainder united with Rohtak.

There are no antiquities of any note, and the history of the old sites is unknown Excavations at the Rohtak Khokra Kot would seem to show that three cities have been successively destroyed there 3 the well- known coins of Raja Samanta Deva, who is supposed to have reigned over Kabul and the Punjab about A. D. 920, are found at Mohan Ban. Jhajjar, Maham, and Gohana possess some old tombs, but none is of any special architectmal merit ; the finest are at the first place. There is an old baoh 01 stepped well at Rohtak and another at Maham : the latter has been described by the author of Pen and Pencil Sketches, and must have been in much better repair m 1828 than it is now. The Gaokaran tank at Rohtak and the Buawala tank at Jhajjar are fine works, while the masonry tank built by the last Nawab of Jhajjar at Chuchakwas is exceedingly handsome. The asthal or Jog monastery at Bohar is the only group of buildings of any architectural pretensions in the District the Jhajjar palaces are merely large houses on the old Indian plan.

[edit] Population

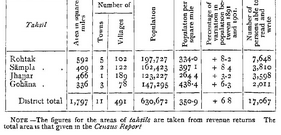

Rohtak contains 11 towns and 491 villages. Its population at each of the last four enumerations was: (1868) 531,118, (1881) 553,609, (1891) 590,475, and (1901) 630,672. It increased Population> by nearly 7 per cent, during the last decade, the increase being greatest in the Sampla tahsil, and least in Jhajjar It is divided into four tahsils ROHTAK, JHAJJAR, SAMPLA, and GOHANA the head-quarters of each being at the place from which it is named. The chief towns are the municipalities of ROHTAK, the administrative head-quarters of the District, JHAJJAR, BERI, BAHADURGARH, and GOHANA.

The following table shows the distribution of population in 1901

Hindus number 533,723, or 85 per cent of the total, and Muham- madans 91,687, About 85 per cent, of the population live in villages, and the average population in each village is 1,096, the largest for any District in the Punjab. The language ordinarily spoken is Western Hindi,

The Jats (217,000) comprise one-third of the population and own seven-tenths of the villages in the District. The great majority are Hindus, and the few Muhammadan Jats are of a distinctly inferior type. The Hindu Rajputs (7,000) are a well-disposed, peaceful folk, much resembling the Jats m their ways; the Ranghars or Muham- madan Rajputs (27,000), on the other hand, have been aptly described as good soldiers and indifferent cultivators, whose real forte lies in cattle-lifting, Many now enlist in Skinner's Horse and other cavalry regiments. The Ahirs (17,000) are all Hindus and excellent culti- vators. There are 9,000 Malls and 3,000 Gujars The Brahmans (66,000) were originally settled by the Jats when they founded their villages, and now they are generally found on Jat estates. They are an inoffensive class, venerated but not respected Of the commercial castes the Banias (45,000) are the most important , and of the menials the Chamars (leather- workers, 55,000), Chuhras (scavengers, 23,000), Dhanaks (scavengers, 21,000), Jhmwars (water-carriers, 12,000), Kum- hars (potters, 13,000), Lohars (blacksmiths, 9,000), Nais (barbers, 13,000), Tarkhans (carpenters, 13,000), and Telis (oil-workers, 7,000). There are 17,000 Fakirs. About 60 per cent, of the population are agriculturists, and 21 per cent industrial.

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel has a branch at Rohtak town, and in 1901 the District contained 41 native Christians.

[edit] Agriculture

The general conditions with regard to agriculture in different parts depend rathei on irrigation than on differences of soil. Throughout the District the soil consists as a rule of a good light-coloured alluvial loam, while a lightei and sandier soil is found on elevations and clay soils in depressions of the land All soils alike give excellent returns with sufficient rainfall, but, unless irrigated, fail entirely in times of drought, though the sandy soil can do with less rain than the clay or loam. The large unirngated tiacts are absolutely dependent on the autumn harvest and the monsoon rains. Roughly speaking, the part north of the railway may be classed as secure, that to the south as insecure, from famine. The whole of the soil contains salts, and saline efflorescence is not uncommon where the drainage lines have been obstructed

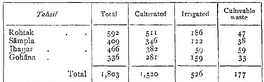

The District is held almost entirely on the pattldan and lhaiydchdra tenures, zamindari lands covering only about 8,000 acres, and lands leased from Government about 5,500 acres The following table shows the mam agncultuial statistics in 1903-4, areas being m square miles :

Wheat is the chief crop of the spring harvest, occupying 103 square miles in 1903-4 , gram occupied 141 and barley 47 square miles. In the autumn harvest the spiked and great millets (bdjra 23\&jowdr) are the principal staples, occupying 338 and 335 square miles respec- tively; cotton occupied 65 square miles, sugar-cane 31, and pulses 138, Indigo is grown to a small extent, but only for seed.

The cultivated area increased from 1,406 square miles m 1879 to 1,520 square miles in 1903-4, in which year it amounted to 84 per cent, of the total area The increase of cultivation during the twenty years ending 1901 is chiefly due to canal extensions, and it is doubtful whether further extension is possible. Fallows proper are not practised; the pressure of population and the division of property are perhaps too great to allow them. For rains cultivation the agriculturist generally sets aside over two-thirds of his lands in the autumn and rather less than one-third in the spiing, and the land gets rest till the season for which it is kept comes round again , if there is heavy ram in the hot season, the whole area may be put under the autumn crop, and in that case no spring crop is taken at all These arrangements are due to the nature of the seasons, rather than to any care for the soil. On

VOL. xxi. x lands irrigated by wells and canals a crop is taken every harvest, as fai as possible , the floods of the natural streams usually prevent any autumn crop, except sugar-cane, being grown on the lands affected by them. Rotation of crops is followed, but in a very imperfect way, and for the sake of the crop rather than the soil, Nothing worth mention appears to have been done in the way of improving the quality of the crops grown.

Except in the Jhajjar tahsil^ where there is a good deal of well- irrigation, advances under the Land Improvement Loans Act were not popular till recent years nor are advances under the Agriculturists' Loans Act common, save in times of scarcity, as the people prefer to resort to the Banias. During the five years ending September, 1904, a total of 5-3 lakhs was advanced, including 4-9 lakhs under the Agriculturists' Loans Act. Of this sum, 3 lakhs was lent in the famine year 1899-1900.

The bullocks and cows are 01 a very good breed, and particulaily fine in size and shape. A touch of the Hansi strain probably pei- vades them throughout. The bullocks of the villages round Beri and Georgegarh have a special reputation, which is said to be due to the fact that the Nawab of Jhajjar kept some bulls of the Nagaur breed at Chuchakwas. This breed is small, hardy, active, and hard-working, but is said to have fallen off since the confiscation of the Jhajjar State. The zammddrs make a practice of selling their bullocks after one ciop has come up, and buying fresh ones for the next sowings, thereby avoiding the expense of their keep for four or five months. The extensive breakmg-up of land which has taken place since 1840 has greatly restricted the grazing grounds of the villages , the present fodder-supply grown in the fields leaves but a small margin to provide against seasons of drought, and in many canal estates difficulty is already being experienced on this score. Few large stretches of village jungle are now to be found, and the policy of giving proprietary giants has reduced by more than half the area of the Jhajjar and Bahadur- garh reserves. A large cattle fair is held at Georgegarh. The horses of the District are of the ordinary mediocre type. Goats and sheep are owned as a rule by village menials. The District board maintains three horse and three donkey stallions.

Of the total area cultivated in 1903-4, 526 square miles, or neaily 36 per cent , were classed as irrigated. Of this area, 453 square miles were irrigated from canals and 72 from wells. The District had 2,903 masonry wells in use, all worked by bullocks on the rope-and-bucket system, besides 864 unbricked wells, water-lifts, and lever wells. Canal- irrigation more than trebled and well-irrigation more than doubled during the twenty years ending 1901. The former is derived entirely from the WESTERN JUMNA. CANAL, the Biitana branch of which (with its chief distributary, the Bhiwani branch) iirigates the Gohana and Rohtak tahsil while various distributanes from the new Delhi branch supply Rohtak and Sampla. The area estimated as annually irrigable from the Western Jumna Canal is 278 square miles There used to be a certain amount of irrigation from the Sahibi and Indori streams, but this has been largely obstructed by dams erected in the territory of the Alwar State, Wells are chiefly found in the south of Jhajjar and in the flood-affected tracts of Sampla

The District contains no forests, except 8 square miles of Govern- ment waste under the control of the Deputy-Commissioner , and, save along canals and watercourses and immediately round the villages, trees are painfully wanting. Reserved village jungles are, however, a featuie of the District and are found in nearly every village.

The Sultanpur salt sources are situated m five villages in Guigaon and in one in this District in the Jhajjai tahsil. A large amount of kankar is found, some of which is particulaily pure and adapted for the preparation of lime. The low hills in the south yield a limestone suitable foi building purposes.

[edit] Trade and communication

The chief manufactures are the pottery of Jhajjar , the saddlery and leather-work of Kalanaur ; muslin turbans, interwoven with gold and silver thread, and a muslin known as tanzeb^ produced at Rohtak; and the woollen blankets woven in all parts. Dyeing is a speciality of Jhajjar. The bullock- carts of the District are well and strongly made. Four cotton-ginnmg factories and one combined ginning and pressing factory have recently been opened at Rohtak town, which absorb a good deal of the raw cotton of the District. In 1904 they employed 279 hands. In other industries the native methods of production are adhered to; and, though in the towns foreign sugar and cloth are making way, native products hold their own in the villages. Owing to the opening of the factories and the Rohtak gram market, the demand for labour has considerably increased and wages have risen.

In ordinary seasons the District exports gram, the annual export of cereals being estimated by the Famine Commission of 1896-7 at 89,000 tons. The construction of the Southern Punjab Railway has greatly facilitated exports at all times, and imports in time of scarcity, the monthly average imported by this line during the famine year 1899 being no less than 3,400 tons. Commerce is also much helped by the Rohtak grain market, owing to its favourable position, its exemption from octroi, and the facilities given for gram storage.

The District is traversed by the Southern Punjab Railway ; the Rewari-Bhatinda branch of the Rajputana-Malwa Railway crosses the west side of the Jhajjar tahsil , and the terminus of the branch from Garhi Harsaru to Farrukhnagar is about a mile from the border. The

x 2 District is also well piovided with loads, the most important being the Delhi-Hissar, Rohtak-Bhiwani, and Rohtak-Jhajjai loads, all of which are metalled. The total length of metalled roads is 79 miles, and of unmetalled roads 605 miles Of these, 20 miles of metalled and 41 miles of unmetalled roads are under the Public Works depart- ment, and the rest under the District board

[edit] Famine

The first famine of which there is any tiustworthy record was that of 1782-3, the terrible chahsa. From this famine a very large number of villages in the District date their refoundation, in whole or in part. Droughts followed in 1802, 1812, 1817, 1833, and 1837. The famine of 1860-1 was the first in which relief was regularly organized by Government Nearly 500,000 daily units were relieved by distribution of food and in othei ways; about 400,000 were employed on relief works; Rs. 34,378 was spent on these objects, and Rs, 2,50,000 of land revenue was ultimately remitted. In 1868-9, 719,000 daily units received relief, 125,000 were employed at various times on relief works, nearly Rs. 1,35,000 was spent in alleviating the calamity, and more than Rs, 2,00,000 of revenue in all was remitted. The special feature of the relief in tbis famine was the amount raised in voluntary subscriptions by the people themselves, which was nearly Rs. 45)- There is said to have been great loss of life, and nearly 90,000 head of cattle died. The next famine occurred m 1877-8. Highway robberies grew common, grain carts were plun- dered, and in the village of Badli a grain riot took place. No relief was, however, considered necessary, nor was the revenue demand sus- pended, 176,000 bead of cattle disappeared, and it took the District many years to recover. Both harvests of 1895-6 were a failure, and in 1896-7 there was literally no crop in the rains-land villages. Relief operations commenced in November, 1896, and continued till the middle of July, 1897, at which time a daily average of 11,000 persons were on the relief works. Altogether, Rs. 96,300 was spent m allevi- ating distress, and suspensions of revenue amounted to 3-4 lakhs. The famine was, however, by no means severe, more than three-fourths of the people on relief works were menials, and large stores of fodder and gram remained m most of the villages. The famine of 1899-1900 was only surpassed m severity by the chalisa famine above mentioned. The spread of irrigation had, however, largely increased the area protected from drought, and, while in 1896-7 the affected area was 1,467 square miles, in 1899-1900 this had shrunk to 1,234, m spite of the greater seventy of the drought. The greatest daily average -of persons relieved was in the week ending March 10, 1900, when 33,632, or 9 per cent. of the population affected, were in receipt of relief. The total cost of the famine was 7-5 lakhs. The total deaths from December, 1899, to October, 1900, were 25,006, giving a death-rate of 69 as compared with the aveiage rate of 37 per 1,000. Fever was lesponsible for 18,279 and cholera foi 1,935 deaths. The losses of cattle amounted to 182,000.

The District is in charge of a Deputy-Commissioner, assisted by three Assistant or Extra-Assistant Commissioners, of whom frustration one is in charge of the District treasury. Each of the four tahsil is under a tahsildar assisted by a naib-tahsildar.

The Deputy-Commissioner, as District Magistrate, is responsible for cnmmal justice. Civil judicial work is under a District Judge \ and both officers are supervised by the Divisional Judge of Delhi, who is also Sessions Judge. The District Judge has two Munsifs under him, one at head-quarters, the other at Jhajjar There are also six honorary magistrates. The predominant form of crime is burglary.

The villages are of unusual size, averaging over 1,000 persons. They afford an excellent example of the bhaiyachara, village of Northern India, a community of clansmen linked together, sometimes by descent from a common ancestor, sometimes by marriage ties, sometimes by a joint foundation of the village , with no community of property, but com- bining to manage the affairs of the village by means of a council of elders ; holding the waste and grazing grounds, as a rule, in common ; and maintaining, by a cess distributed on individuals, a common fund to which public receipts are brought and expenditure charged.

The early revenue history under British rule naturally divides itself into two parts that of the older tiacts which form most of the area included in the three northern tahsil, and that of the confiscated estates which belonged befoie the Mutiny to the Nawabs of Jhajjar and Bahadurgarh. Thus the regular settlements made in 1838-40 included only half the present District. The earlier settlements made in the older part followed Regulation IX of 1805, and were for short terms, In Rohtak little heed was paid to the Regulation, which laid down that a moderate assessment was conducive equally to the true interests of Government and to the well-being of its subjects. The revenue in 1822 was already so heavy as to be nearly intolerable, while the unequal distribution of the demand was even worse than its bur- den. Nevertheless an increase of Rs. 2,000 was levied in 1825 and Rs. 4,000 shortly after. The last summary settlement made in 1835 enhanced the demand by Rs. 20,000. The regular settlement made between 1838 and 1840 increased the assessment by Rs, 14,000. This was never paid, and the revision, which was immediately ordered, re- duced it by ij lakhs, or 16 per cent. The progress of the District since this concession was made has been a continuing proof of its wisdom.

Bahadurgarh and Jhajjar were resumed after the Mutiny. The various summary settlements woiked well on the whole, and a regular bettlement was made between 1860 and 1863,

The settlement of the whole District was revised between 1873 and 1879. Rates on irrigated land varied from Rs, 2 to Rs. 2-12, and on unirngated land from 5 annas to Rs. 1-9. Canal-irrigated land was, as usual, assessed at a 'dry' rate, plus owners' and occupiers' lates. The result of the new assessment was an increase of 9^ per cent, over the previous demand. The demand for 1903-4, including cesses, amounted to nearly 1 1 lakhs. The average size of a proprietary holding is 5 acres

The collections of land revenue alone and of total revenue are shown below, in thousands of rupees

The District contains five municipalities, ROHTAK, BERI, JHAJJAR, BAHADURGARH, and GOHANA ; and ten ' notified areas,' of which the most important are MAHAM, KALANAUR, MUNDLANA, and BUTANA. Outside these, local affairs are managed by a District board, whose income amounted in 1903-4 to Rs, 1,24,000 The expenditure in the same year was Rs. 1,22,000, the principal item being public works.

The regular police force consists of 433 of all ranks, including 63 municipal police, under a Superintendent, who is usually assisted by 2 inspectors. The village watchmen number 702. The District has 10 police stations, 4 outposts, and 17 road-posts Three trackers and three camel sowars now form part of the oidmary force. The District jail at head-quarters has accommodation for 230 prisoners.

The standard of education is below the average, though some pro- giess has been made, Rohtak stands twenty-sixth among the twenty- eight Districts of the Punjab in respect of the literacy of its population In 1901 only 2-7 per cent, of the population (5 males and o-i females) could read and write. The number of pupils under instruction was 2,396m 1880-1, 3, 380 in 1890-1, 5,097 in 1900-1, and 5,824 in 1903-4. In the last year the District possessed 9 secondary and 65 primary (public) schools and 2 advanced and 42 elementary (private) schools, with 211 girls in the public and 8 in the private schools. The Anglo- vernacular school at Rohtak town with 262 pupils is the only high school, The other principal schools are two Anglo-vernacular middle schools supported by the municipalities of Jhajjar and Gohana, and 6 vernacular middle schools. The total expenditure on education in 1903-4 was Rs. 44,000, chiefly derived from District funds; fees provided nearly a third, and municipal funds and Provincial grants between them a fifth, of the total expenditure.

Besides the Rohtak civil hospital, the District possesses five outlying dispensaries. These in 1904 treated a total of 59,714 out-patients and 1,0 1 6 in-patients, while 2,894 opeiations weie performed The income was Rs. 1 0,000, almost entirely derived from Local and municipal funds.

The number of successful vaccinations in 1903-4 was 14,406, repre- senting 22 8 per 1,000 of population. The towns of Rohtak and Beii have adopted the Vaccination Act.

[D. C. J. Ibbetson, District Gazetteer (1883-4); H. C. Fanshawe, Settlement Report (1880).]