Lushai Hills

(Created page with " {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> This article has been extracted from <br/> THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908.<br/> OXFORD, A...") |

Revision as of 15:41, 1 February 2015

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Lushai Hills

Physical aspects

District in Eastern Bengal and Assam, lying between 22° 19' and 24° 19' N. and 92° 16' and 93° 26' E., with an area of 7,227 square miles. It is bounded on the north by Sylhet and Cachar, and the State of Manipur ; on the west by the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the State of Hill Tippera ; on the south by Northern Arakan and the Chin Hills; and on the east by the Chin Hills.

The whole surface is covered with ranges of hills, which run almost due north and south, with an average height of about 3,000 feet on the west, rising to 4,000 feet farther east, and here .The sides of the hills covered with forest and dense bamboo jungle, except in those places where they have been cleared for cultivation, and a stream or river is invariably to be found in the narrow valleys at their feet. The most important of these rivers are the Tlong or Dhaleswari, the Sonai, and the Tuivol, which drain the northern portion of the country and eventually fall into the Barak. The southern hills are drained by the Koladyne on the east, with its tributaries the Mat, Tuichang, Tyao, and Tuipui ; while the Karna- phuli, at the mouth of which stands Chittagong, with its tributaries the Tuichong, Kao, Deh, Phairang, and Tuilianpui, forms the western drainage system.

The drainage-levels of the country are unusually complicated. The Tlong for some 40 miles of its length runs due north, while parallel to it, on the east the Mat, and on the west the Deh, flow due south. In the same way, the Tuivol and Tuichang and the Tuilianpui and Gutur have parallel courses for many miles, but run in opposite directions. The Tuichong and Phairang flow north till they join the Deh, which then turns west and delivers their combined waters into the Karnaphuli, which flows south-west. Scattered about the District are several plains of considerable size.

These have, as a rule, an elevation of about 4,500 feet, and are covered with a thick layer of rich alluvial soil. They are surrounded by hills, which slope gently towards the plain but are generally very steep and often pre- cipitous on the other side. Through the centre runs a sluggish stream, which escapes through a narrow gorge, below which is generally a fall of some height. It has been suggested that these plains are the silted- up beds of lakes, a conjecture which is rendered the more probable by the fact that there are several lakes which at present have no outlet, and which must in course of time silt up till the water overtops the lowest point in the surrounding chain of hills. The largest of these plains is Champhai, which has a length of about 7 miles and at the widest point is nearly 3 miles across.

The hills consist of sandstones and shales of Tertiary age, thrown into long folds, the axes of which run nearly north and south. The rocks are a continuation southwards of those forming the Patkai range, and were probably laid down in the delta or estuary of a large river issuing from the Himalayas in the Tertiary period. Marine fossils of that age have been found near Lungleh, embedded in nodular dark grey sandstone.

The hill-sides are generally covered with dense forest or bamboo jungle. Palms, which are common on the lower slopes, give place to various members of the Ficus family ; and such trees as garjafi {Dipterocarpus turbiiiatiis), gugera or maku {Schima IVallichii), oaks, chestnuts, and firs grow on the higher ridges. Herbaceous plants are not common, but ferns and orchids are found in large quantities.

Vrild animals include elephants, rhinoceros, bison, various kinds of deer, gural, and serow {IVemorhaedus), tigers, leopards, the Himalayan black bear {Ursus torquatus), and the Malay bear {Ursus malayanus). The mithati or gayal {Bos froritalis) is kept in domestication. Small game include jungle-fowl and several kinds of pheasant.

The valleys are malarious and unhealthy ; and during the rains the chmate, even on the lower hills, is moist and enervating, and malarial fevers are common everywhere. On the higher ridges it is fairly cool and pleasant even at the hottest seasons of the year. In March and April violent storms from the north west sweep over the hills. The District, like the rest of Assam, enjoys an abundant rainfall. The average fall at Aijal, in the northern hills, is 80 inches in the year, but farther south the precipitation is still heavier, and at Lungleh 131 inches are usually recorded. The rainfall is generally well distributed and the crops seldom suffer from drought.

History

The history of the Lushai Hills, as far as known, is the history of a backwash or eddy of the great wave of immigration that is gener- ally believed to have started from North- West China and spread over Assam and southwards towards the sea. In the Lushai Hills the movement for the last hundred years has been northwards ; and at the beginning of the nineteenth century certain tribes, known as the Old Kukis, were driven from this country, and finding no safety in the plains of Cachar, settled in the hills to the north of the Surma Valley. Fifty years later there was another immigration of hillmen, called New Kukis to distinguish them from their predecessors, who were driven from the southern hills by the Lushais, who made their first appearance on the Chatachara range in 1840. Prior to the advent of the British, the hillmen had been accustomed to make periodical descents upon the plains ; and in 1849 four separate raids were committed, one of them on a village within 10 miles of Silchar, in which 29 of the inhabitants were killed and 42 taken captive.

These outrages were followed by an e.xpedition led into the hills by Colonel Lister, who in 1850 surprised and destroyed the village of Mullah, one of the chiefs concerned in the raid. This demonstration kept the hillmen quiet for some years ; but in 1862 they broke out afresh, and the diplomatic efforts that followed had little practical effect.

In the cold season of i868-g

raids were made on Manipur and Sylhet, and the Noarband and

Maniarkhal tea factories in Cachar were burnt and plundered. An

expedition was dispatched into the hills, but it started too late in

the season and failed to inflict the punishment required. In January,

187 1, a determined raid was made down the Hailakandi valley. The

village of Ainakhal was burnt and twenty-five persons killed, the Alex-

andrapur tea factory was destroyed, a tea planter — Mr. Winchester —

murdered, and attacks were made upon four other tea gardens with

varying success.

The raiders were eventually driven off, but not before they had succeeded in killing twenty-seven persons in addition to those already mentioned, seven of whom were sepoys sent to protect the outlying gardens. Raids were also made on Sylhet, Hill Tippera, and Manipur. Such violent and ferocious forays called for vigorous measures of repression, and in the cold season of 187 1-2 two columns were sent into the hills, one from Chittagong, the other from Cachar. This ex- pedition was completely successful, and the peace of the Assam frontier remained undisturbed for the next twenty years.

In 1888 two serious raids were committed in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. In one the attacking party killed Lieutenant Stewart and two corporals of his regiment ; in the other they cut up the inhabitants of a village located only 8 miles from Demagiri. The following cold season a small force was sent into the hills to exact reparation for these outrages, and a stockaded post was built at Lungleh and gar- risoned by 200 men. This demonstration of military activity had little effect upon the Lushais \ and at the very time when the expedition was in the hills, Lianphunga, a son of Sukpilal, dispatched a raiding party which devastated the Chengri valley on the Chittagong frontier. Prompt measures for reprisal were taken, and columns were dispatched into the hills from Silchar and Chittagong during the following cold season. The captives were surrendered and the offending village burnt ; but the British Government had at last come to the decision that here, as elsewhere, the only effective method of protecting the frontier was the establishment of fortified posts in the hills themselves.

Stockades were accordingly erected at Fort Tregear in the South Lushai Hills, and at Aijal and Changsil in North Lushai. A Political officer, Captain Browne, was stationed in the northern hills, and at first all seemed progressing favourably. Suddenly, without a word of warning, the Lushais rose in September, 1890, attacked the two stockades, and killed Captain Browne, who was marching along the road with an escort of four sepoys. A force was immediately sent up from Cachar, and though Lieutenant Swinton, the officer in command, was killed, Aijal and Changsil were relieved without delay. Active operations were then commenced, and within two months only one of the western chiefs responsible for this disturbance was at large. On April i, 1891, the South Lushai Hills, which had been controlled by an Assistant Political officer under the Commissioner of Chittagong, were formed into a District and placed under a Superintendent.

At the beginning of 1892 the Lushai country was to all appearances in a condition of profound peace, and Mr. McCabe, the Political officer of North Lushai, proceeded to the village of a chief named Lalbura, who had declined to comply with a requisition sent to him for coolies. He was attacked there by a party of Lushais ; but they were driven off, and a force of police was then sent to the hills east of the Sonai, as the chiefs in this quarter had assisted Lalbura in his rising.

Captain Shakespear, the Superintendent of the South Lushai Hills, heard of the attack on Mr. McCabe, and marched northwards to his assistance. When he reached Vansanga's village, the whole country rose in arms, and he was compelled to entrench himself and act on the defensive. The Lushais made constant attacks upon his camp, attempted Lungleh, threatened Demagiri, cut the telegraph wires, and spread themselves over the line of communications. Captain Shake- spear was reheved by a column dispatched from Burma, and the combined forces then proceeded to inflict such punishment as they could during the short time that their scanty supplies enabled them to remain in the field. In December, 1892, a punitive expedition was dispatched into the hills, which co-operated with a column sent from Aijal, and impressed upon the rebellious villages a sense of the futility of attempting to resist the British Government. No active opposition was encountered, and since that date the peace of the District has been undisturbed. In 1898 the South Lushai Hills were transferred to the Assam Administration, and the District for the first time took its present form.

Population

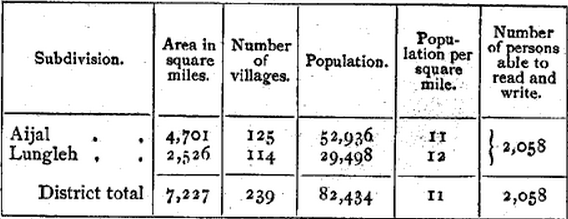

The first complete Census of the Lushai Hills was taken in 1901, and disclosed a population of 82,434, living in 239 villages. The following table gives for each sub- division particulars of area, villages, population, &c. : —

The hills are very sparsely peopled, and only support 11 persons per square mile. An unusual feature in the constitution of the population is the great preponderance of females, there being 1,113 women to every 1,000 men. More than 95 per cent, of the people profess no other creed than Animism, and a Uttle more than 4 per cent, are Hindus. All of these Hindus are foreigners, most of them being members of the military police battalion and their dependents. The number of the native Christians is still very small (26), but it was only in 1897 that the Welsh Presbyterian Mission undertook to carry on the work which had been begun by two pioneer missionaries. About 87 per cent, of the population of the hills returned Lushai or Dulien as their usual form of speech, a language which is akin to the Old Kuki ' dialect Rangkhol, and to various forms of speech used by the Naga tribes. Agriculture was the means of support of 93 per cent, of the population in 1901.

The inhabitants of the hills are said to be all members of the same race, but are divided up into a number of families or clans. These clans are distinguished from one another by differences in sacrificial ritual and in some cases by differences in dialect, but all enjoy the ius connubii. The principal subdivisions are the Lushais (36,400), who supply chiefs to nearly every village in the hills; the Poi (15,000), or immigrants from the Chin Hills ; the Hmar (10,400), or tribes who have come from Manipur; and the Ralte (13,800), Paithe, Thado, and Lakher. The other groups into which the population is divided are rapidly losing their distinctive traits.

The Lushais, to apply one generic term to all the inhabitants of the hills, are a short and sturdy race, with countenances of a distinctly MongoHan type, and well-developed legs. The men seldom have hair upon their faces, and pick out what little grows, with the exception of a few shoots at the corners of the mouth. Both sexes draw their hair tight back and tie it in a knot, and wear a coat which reaches below the waist, and a shawl thrown over the shoulders. Women, in addi- tion, wear a blue petticoat, reaching to the knee, and ivory rings about i^ inches in diameter in their ears. Amber necklaces and rough uncut carnelians are highly prized. Their arms are flint-lock muskets, daos or billhooks of the Burmese pattern, and an inferior kind of spear.

The people live in villages, each of which is ruled by a chief, who is entirely independent. The chief is supreme ; but if his subjects dislike his system of administration, they move elsewhere. He settles all disputes, decides where the village is to cultivate, and when and where it shall be moved. His house is the poorhouse of the com- munity, and orphans and indigent persons live there and get food in return for labour. The other officials are the iipa or councillors, the crier, the blacksmith, and the pui-thiam or sorcerer.

Villages are generally built on the top of a ridge or spur, and before the British occupation of the hills were strongly stockaded. The houses are laid out in streets radiating from a central square, in which stand the chiefs house and the house where strangers and the young unmarried men of the village sleep. They are built on piles on the natural slope of the hill, and at the end nearest the road is a rough platform of logs. The doorway has a high sill, and the door consists of a sliding panel of bamboo work.

On each side of the fireplace are bamboo sleeping platforms, and beyond is a kind of lumber room, from which a door opens on a small back veranda. Windows in the side of the house are considered unlucky, unless the right to make them has been purchased by killing two ?>nihan and feasting the village — a curious instance of a savage form of window tax, and an example of the material gains accruing from many of the religious beliefs and superstitions of the hill tribes of Assam. The posts used are of timber, but the walls, floor, and roof frame are made of bamboo. The roof is generally thatched with cane leaves, tied down with broad bands of split bamboo.

In spite of the fact that women exceed the men in numbers, the Lushai bachelor has to pay heavily for his wife. The price paid to the father or nearest male relative of the girl varies from three to ten inithan, for it is always stated in terms of these animals, though cash or other articles may actually be given in their place. But the father is by no means the only person whose demands have to be satisfied. The girl's aunt receives from Rs. 5 to Rs. 40, the nearest male relative on her mother's side from Rs. 4 to Rs. 40, the eldest sister gets a small sum as a reward for having carried about the bride when young, and there are also the male and female protectors of the bride to each of whom a present must be given.

The result is that it not unfrequently happens that a man dies with his obligations still undischarged, and leaves to his children the task of paying for their mother. The essen- tial part of the marriage ceremony is a feast to the friends and rela- tions, and the sacrifice of a fowl by the pui-thiam. For some time after the wedding the bride sleeps with her husband, but returns every day to her father's house. Divorce by mutual consent is recognized ; but under these circumstances the husband recovers no part of the bride's price, so that he has every inducement to make the best of the lady he has chosen.

Unmarried girls are not expected to remain chaste ; but if a lover begets a child, he is required to pay one mithan to its maternal grandfather, unless he marries the object of his affec- tions, when the ordinary bride price only is charged. Among the Paithes the marriage ceremony is not performed till the woman has given evidence of her fertility. If she remains barren, the match is broken off. During the first seven days of its life, the spirit of a child is supposed to spend part of its time perched on the bodies of both its parents, and for fear of injuring it they have to keep quiet during this period. By this means primitive man ensures that the mother shall have a short period of repose.

After death, the corpse is dressed in its best clothes and fastened to a bamboo frame in a sitting posture. A big feast is then given to the friends and neighbours, and food and drink are offered to the corpse. On the evening following the death, the body is interred just opposite the house, the grave consisting of a shaft about 4 or 5 feet deep, from which a tunnel branches off in which the corpse is placed. People who belong to wealthy families are not buried at all. They are placed in a hollow tree-trunk, the lid of which is carefully plastered with mud, and put beside a fire in the centre of the house. A hollow bamboo connects the coffin with the earth, and drains off liquid matter. The nearest relatives sit beside the coffin and drink rice-beer, and at the end of three months the bones are collected and stored in a basket. The Paithes smear a greasy preparation over the corpse, which preserves and hardens the skin. It is then dressed up, and in the evening is brought out, and rice-beer is poured down its throat, while the people sing and dance around it. This disgusting performance is sometimes kept up for several months.

The religion of the Lushais is of the usual animistic kind. They believe in a Creator, who does not trouble himself much with the subsequent fate of the world he has created, and most of their religious energies are devoted to the propitiation of the evil spirits, who are supposed to be the cause of all misfortune. I^ike many of the other hill tribes, they recognize two degrees of happiness after death — the greater joy being reserved for those who have killed men or animals in the chase, or have feasted the village. Women can only enter this abode of bliss if taken there by their husbands, so a premium is placed on wifely obedience and devotion. Existence in the ordinary spirit world is thought to be far from pleasant. After a certain time, the soul is born again in a hornet, and presently is converted into water. If in the form of dew it falls upon a man, it is born again on the earth in the shape of his child.

In wealthy families when a son marries he receives a certain number of houses and becomes an independent chief. At the same time a share of his father's guns, necklaces, and other valuables and slaves are made over to him. The youngest son remains with his father till his death and then succeeds to the village. Much the same custom prevails among the common people.

Agriculture

Like other hill tribes, the Lushais follow the system oijhfim cultiva- tion. The jungle growing on the hill-side is cut down and burnt, the ground is cleared of logs which were too large to burn, and the seeds of rice, maize, millet, vegetables, and cotton are dibbled in among the ashes. The largest yield is obtained from land which has just been cleared of virgin forest, or which has not been disturbed for forty or fifty years. Land that bears a heavy growth of bamboo jungle is also highly esteemed, but hill- sides covered with ikm {Saccharum arundinaceuin) and grass are said to yield very poor harvests, though good crops are obtained from such land in the Naga Hills. The only agricultural implements used are daos, axes, and hoes.

The dao is a knife with a triangular blade about three inches wide at the end and half an inch wide at the handle, which is used to cut down the jungle and to make the holes in which the seeds are planted. The axes and hoes are small and light. It is only where land has not been cultivated for many years that a crop of rice is taken from it in two successive seasons, though peas and beans are often sown on jhums- cleared in the previous year. Land covered with bamboos can be cropped every fourth year, but land under forest is allowed six to nine years' rest. The cultivation is thus of a migra- tory character, and the villages are shifted at intervals of about five years to enable the cultivator to live near his fields. The area under cultivation is not known, and there are no means of estimating its extension or decrease. Little attempt has as yet been made to improve the existing staples or to introduce new varieties. The cultivation of irrigated rice has, however, been tried in various parts of the District, and has been adopted by a few of the Lushais.

The live-stock include tame mithan, pigs, goats, and dogs. Pigs are carefully tended, and treated almost as pets ; the goats are of the long-haired hill breed. Dogs are used for food, and are said to be similar to those eaten by the Chinese. They are of medium size, with long yellow hair, short legs, a bushy and tightly curled tail, and a pointed nose, and are in great requisition for sacrificial purposes.

The District has never been properly explored by a geologist ; but the officer of the Geological Survey department who accompanied the expedition of 1889-90 found no traces of coal, limestone, or other minerals of economic value either in the rocks through which the road was cut or in the debris brought down by the rivers.

Trade and Communication

The only articles manufactured in the District are earthen pots and pipes, the daos, hoes, and axes required for cultivation, and cotton cloths. These cloths are woven from yarn spun Trade and homegrown cotton, and are superior to those usually manufactured by the hill tribes, ihey are, however, produced only in sufficient quantities to clothe the members of the family, and are seldom sold. Such trade as exists is in the hands of Bengalis or merchants from Rajputana, and there are only two or three Lushai shopkeepers in the whole District. The principal imports are food-stuffs, cloth, iron, daos, brass pots and umbrellas, while forest produce is exported.

A bridle-path runs from Silchar to Aijal, the head-quarters of the District, a distance of 120 miles; but heavy goods are usually brought up the Dhaleswari river to Sairang, 13 miles from Aijal. The journey between Silchar, the place at which passengers usually embark, and Sairang occupies from twelve to twenty-one days up and from four to six days down-stream. Bridle-paths run from Aijal to Falam, Lungleh, and North Vanlaiphai, and from Lungleh to Haka and Demagiri, on the route to Chittagong. Altogether 4 miles of cart-road and 542 miles of bridlepaths were maintained in 1903-4.

Famine

The country never suffers from want of rain, but in 1881 there was scarcity, due to the depredations of rats. In the previous season the bamboos had seeded, and the supply of food thus provided caused an immense multiphcation in the numbers of these rodents, which, when they had exhausted the bamboo seed, devoured the rice crop. The Lushais descended into the Surma Valley in search of work and food, and Government sent about 750 tons of rice into the hills.

Administration

For general administrative purposes the District is divided into two subdivisions : Aijal, under the immediate charge of the Superintendent of the Hills, who is a member of the Assam Com- mission ; and Lungleh, under a European police officer. Public works are in charge of a District Engineer, who is under the orders of the Superintendent of the Hills, and a Civil Surgeon is stationed at Aijal. The political organization of the Lushais themselves is considerably in advance of that usually found among the hillmen of Assam. Their chiefs possess considerable influence and power, and the Government is thus able to deal with responsible individuals. Advantage has been taken of this in the internal adminis- tration of the District.

The Aijal subdivision is divided into twelve and the Lungleh subdivision into six circles. In each of these circles an interpreter is stationed, through whom all orders are transmitted to the village chiefs, and who is responsible for seeing that these orders are carried out. He is also required to submit regular reports on all events occurring within the circle and on the state of the crops. In each village a writer has been appointed, who prepares and keeps up a house list, and in return for this is exempted from payment of house tax and from labour on the roads. The chiefs and headmen of villages are held responsible for the behaviour of their people, their authority is upheld by Government, and litigation generally and any tendency to appeal against the orders of the chiefs in petty cases is discouraged.

All criminal and civil cases which are not disposed of by the chiefs themselves are heard by the Superintendent and his assistants. The Superintendent exercises powers of life and death, subject to confirma- tion by the Lieutenant-Governor, who is the chief appellate authority. The High Court at Calcutta has no jurisdiction in the hills, except in criminal cases against Europeans. . .

Land revenue is not assessed, but the people pay a tax of Rs. 2 a house. In addition to this money tax, the Lushais are required to provide labour when required by Government, but the coolies so employed receive the liberal wage of eight annas a day.

The civil police force includes 2 sub-inspectors and 49 head con- stables and men ; but the real garrison of the District consists of a battalion of military police under three European officers, with a sanctioned strength of 800 officers and men. A small jail at Aijal has accommodation for 13 prisoners.

In 1903-4 there were two schools at Aijal, one maintained by Government, and one by the Welsh Presbyterian Mission ; and Govern- ment schools at Lungleh and Khawmbawk. The total number of pupils in the Government schools was only 175, and the expenditure on education amounted to Rs. 3,524, the greater part of which was met from Pro\ incial revenues. For a savage tribe who have so recently come under British rule, the Lushais show a considerable aptitude for civilization. In 1901, 2-5 per cent, of the population (5-1 males and o-i females) were able to read and write, a proportion much higher than in Manipur or in the Naga or Garo Hills. This difterence is probably due to the aristocratic organization of their community. "When arrangements were being made for the Census of 1901, it was found that some villages had not a single literate person to act as enumerator. A man was then selected by the chief and sent to head- quarters, in order to be taught how to read and write.

The District possesses 7 dispensaries and 5 military police hospitals, with accommodation for 144 in-patients. In 1904 the number of cases treated was 34,000, of whom 1,200 were in-patients, and 300 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 14,400, which was entirely met from Provincial revenues.

Vaccination is not compulsory in any part of the District, and the Lushais have not suffered sufficiently from small-pox to be fully alive to its value as a prophylactic. In 1903-4 only 20 per 1,000 of the population were vaccinated, a figure far below the average for the Province as a whole.

[B. C. Allen, Gazetteer of the Lushai Hills (1906). A monograph on the Lushais is under compilation.]