Naini Tal District, 1908

(Created page with "=Naini Tal District, 1908= ==Physical aspects== Southern District in the Kumaun Division, United Provinces, lying between 28° 51' and 29° 37' N. and 78° 43' and 80° 5'...") |

Revision as of 15:08, 12 March 2015

Contents |

Naini Tal District, 1908

Physical aspects

Southern District in the Kumaun Division, United Provinces, lying between 28° 51' and 29° 37' N. and 78° 43' and 80° 5' E., with an area of 2,677 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Districts of Almora and Garhwal ; on the east by Almora and by Nepal territory ; on the west by Garhwal and Bijnor ; and on the south by Pllibhit, Bareilly, Moradabad, and the State of Rampur. About one-sixth of the District lies in the outer ranges Of the Himalayas, the chief of which is known as aspects. Gagar. These rise abruptly from the plains to a height of 6,000 or 7,000 feet, and are clothed with forest. The scenery is strikingly beautiful ; and from the tops of the higher peaks, which reach a height of nearly 9,000 feet, magnificent views can be obtained of the vast level plain to the south, or of the mass of the tangled ridges lying north, bounded by the great snowy range which forms the central axis of the Himalayas. Immediately below the hills stretches a long narrow strip of land called the Bhabar, in which the mountain torrents sink and are lost, except during the rains, beneath the boulder formation which they themselves have made. The Bhabar contains vast forest areas, and is scantily culti- vated. The remainder of the District is included in the damp moist plain known as the Tarai and the Kashipur tahsil. On the northern edge of the Tarai springs appear, which gradually form rivers or small streams, and give a verdant aspect to the country throughout the year. Kashipur, in the south-west corner, is less swampy and resembles the adjoining tracts in Rohilkhand. None of the rivers in the District rises in the snowy range except the Sarda, which just touches the eastern boundary. The main drainage lines of the hill country are those of the Kosi, Gola, and Nandhaur. The KosT rises in Almora District, and the Gola and Nandhaur in the southern slopes of the outer hills. All three rivers eventually join the Ramganga, the Gola being known in its lower courses as the Kichha, and the Nandhaur as the Deoha and later as the Garra. The smaller watercourses of the Bhabar and the Tarai are innumerable, and change their names every few miles, but all eventually drain into the Ramganga. In the hills are several lakes of some size and considerable beauty, the chief being Naini Tal, Bhim Tal, Malwa Tal, Sat Tal, Naukuchhiya Tal, and Khurpa Tal.

The Tarai consists of a zone of recently formed Gangetic alluvium, while the Bhabar is a gently sloping mass of coarse gravels still being formed from the debris brought down by streams from the hills. A sub-Himalayan zone of low hills, including the Kotah Dun, which resembles the Siwaliks and the valley of the Nandhaur, contains deposits of the Upper Tertiary age, chiefly Nahan sandstone. This zone is separated from the Himalayas by a reversed fault. The higher hills comprise an older set of slates and quartzites ; a massive dark dolomite or limestone ; beds of quartzite and basic lava-flows, and possibly other schistose and granitic rocks. The steep slopes acted on by heavy rain- fall have from time to time given way in landslips of considerable size ^

The flora of the District presents a great variety. In the Tarai the ordinary trees and plants of the plains are found. The Bhabar forests consist to a large extent of sal (Shorea robusta) ; but as the hills are ascended the flora changes rapidly, and European trees and plants are seen Records, Geological Stii-vey of India, vol. xxiii, pts. i and iv, and vol. xxiv, pt. ii ; T. H. Holland, Report on Geological Structure of Hill Slopes near Naini Tal. For a complete list of plants found, see chap, viii, A^.-JF. P. Gazetteer, vol. x, 1882.

Owing to the wide range of climate and elevation, most of the

animals of both the plains and hills of Northern India are found in this

District. A few elephants haunt the Bhabar and part of the Tarai,

while tigers and leopards range from the plains to the hills. The wolf,

jackal, and wild dog are also found. The Himalayan black bear lives

in the hills, and the sloth bear in both the Bhabar and the Tarai. The

sambar or jarau, spotted deer, swamp deer, hog deer, barking-deer,

four-horned antelope, nilgai, antelope, and gural also occur. Many

kinds of snakes are found, including immense pythons which some-

times attain a length of 30 feet. The District is also rich in bird life ;

about 450 species have been recorded. Fish are plentiful, and fishing

in the lakes and some of the rivers is regulated by the grant of

licences.

The climate of the Tarai and to a lesser extent of the Bhabar is exceedingly unhealthy, especially from May to November. Few people, except the Tharus and Boksas, who seem fever-proof, are able to live there long. In the hills the climate is more temperate, and the annual range on the higher slopes is from about 26° in January, when snow falls in most years, to 85° in June.

The rainfall varies as much as the chmate. At Kashipur, south of the Tarai, only 46 inches are received annually ; while at HaldwanI, in the Bhabar, the average is nearly 77. Naini Tal is still wetter, and receives 95 inches annually, including snow.

History

Traditions connect many places in the hills with the story of the Mahabharata. The earliest historical record is to be found in the visit of Hiuen Tsiang, who describes a kingdom of Govisana, which was probably in the Tarai and Bhabar, and a kingdom of Brahmapura in the hills. The Tarai then appears to have relapsed into jungle, while the hills were included in the dominion of the Katyuri Rajas, of whom little is known. They were succeeded by the Chands, who claimed to be Sombansi Rajputs from Jhus! in Allahabad District, and first settled south of Almora and in the Tarai. The Musalman historians mention Kumaun in the fourteenth century, when Gyan Chand proceeded to Delhi and obtained from the Sultan a grant of the Bhabar and Tarai as far as the Ganges. The lower hills were, however, held by local chiefs, and Kirati Chand (1488-1503) was the first who ruled the whole of the present District. When the Mughal empire was established the Musalmans formed exaggerated ideas of the wealth of the hills, and the governor of the adjoining tract occupied the Tarai and Bhabar and attempted to invade the hills, but was foiled by natural difficulties. The Ain-i-Akbaj-i mentions a sarkdr of Kumaun, but the uiahdls included in it seem to refer to the submontane tract alone. The pov/er of the Chand Rajas was chiefly confined to the hill tracts; but Baz Bahadur (1638-78) visited Shah Jahan at Delhi, and in 1655 joined the Mughal forces against Garhwal, and recovered the Tarai. In 1672 he introduced a poll-tax, the proceeds of which were remitted to Delhi as tribute. One of his successors, named Debl Chand (1720-6), took part in the intrigues and conspiracies of the Afghans of Rohilkhand and even faced the imperial troops, but was defeated. In 1744 All Muhammad, the Rohilla leader, sent a force into the Chand territory and penetrated through Bhim Tal in this District to Almora ; but the Rohillas were ultimately driven out. A reconciliation was subsequently effected ; troops from the hills fought side by side with the Rohillas at Panipat in 1 76 1, and the lowlands were in a flourishing state. Internal dissen- sions followed, and the government of the plains became separated from that of the hills, part being held by the Nawab of Oudh and part by Brahmans from the hills. In 1790 the Gurkhas invaded the hill tracts, and the Chands were driven to the Bhabar and finally expelled. The Tarai and Kashipur were ceded to the British by the Nawab of Oudh in i8or with the rest of Rohilkhand. In 18 14 war broke out between the British and Nepalese, and a force marched from Kashipur in February, 1815. Almora fell in two months and Kumaun became British territory. The later history of the District is a record of administrative details till 1857. The inhabitants of the hills took no part in the great Mutiny ; but from June there was complete disorder in the plains, and large hordes of plunderers invaded the Bhabar. Unrest was spreading to the hills, when martial law was proclaimed by Sir Henry Ramsay, the Commissioner, and the danger passed. The rebels from Rohilkhand seized Haldwani near the foot of the hills ; and attempts were made to reach Naini Tal, but without success. By February, 1858, the rebels were practically cleared out of the Tarai, and there was no further trouble.

There are considerable areas of ruins in the Tarai and Bhabar which have not been properly explored. Near Kashipur bricks have been found bearing inscriptions of the third or fourth century a.d. The temple at Bhim Tal, built by Baz Bahadur in the seventeenth century, is the chief relic of the Chands.

Population

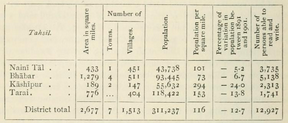

The District contains 7 towns and 1,513 villages. Population increased considerably between 1872 and 1891, but was then checked by a series of adverse seasons. The numbers at the four enumerations were as lollows : (1872) 263,956, (1881) 339,667, (1891) 356,881, and (1901) 311,237. The Tarai and Bhabar contain a large nomadic population. There are four divisions, corresponding to the tahsiis of Districts in the plains : namely, Naini Tal, the Bhabar, the Tarai, and Kashipur. The Bhabar is in charge of a tahsilddr stationed at Haldwani, and the Tarai is under a tahsildar at Kichha. The principal towns are the municipalities of NainI Tal, the District head-quarters, and KashTpur, and the 'notified area' of Haldwani, The following table gives the chief statistics of population in 1901 : —

About 75 per cent, of the population are Hindus, and more than 24 per cent. Musalmans ; but the latter are chiefly found in the Tarai and Kashipur. More than 67 per cent, of the total speak Western Plindi, 31 per cent. Central Pahari, and i per cent. Nepali or Gorkhali.

In the hills and Bhabar the majority of the population is divided into three main castes — Brahmans, Rajputs, and Doms. The two former include the Khas tribes classed respectively as Brahmans and Rajputs. The Doms are labourers and artisans, while the Brahmans and Rajputs are agriculturists. In the Tarai and Kashlpur are found the ordinary castes of the plains, with a few peculiar to this tract. Rajputs altogether number 51,300 ; Brahmans, 36,000 ; Doms, 33,000 ; and Chamars, 23,000. The Tharus and Boksas, who are believed to be of Mongolian origin, number 16,000 and 4,000 respectively. They are the only people who can retain their health in the worst parts of the Tarai. In the hills are found three small, but peculiar, castes : the Bhotias, who come from the border of Tibet ; the Naiks, who devote their daughters to prostitution ; and the Sauns, who are miners. Among Musalmans the chief tribes are the Shaikhs (19,000), and Julahas or weavers (13,000). The Rains (4,000) and the Turks (4,000) are found only in the submontane tract. Agriculture supports about 67 per cent, of the total population, and general labour 9 per cent.

Out of 659 native Christians in 1901, Methodists numbered 2or, Roman Catholics 193, Presbyterians 59, and the Anglican communion 38. The American Methodist Episcopal Mission commenced work at NainI Tal in 1857.

Agriculture

In the hill tracts the method of cultivation differs according to the situation of the land. Plots lying deep in the valleys near the beds of rivers are irrigated by small channels, and produce a constant succession of wheat and rice. On the hill-sides land is terraced, and jnarud, or some variety of bean or pulse, takes the place of rice in alternate years, while wheat is not grown continuously unless manure is available. In poorer land barley is grown instead of wheat. Potatoes are largely cultivated on the natural slope of hill-sides from which oak forest has been cut. Cultivation in the hills suffers from the fact that a large proportion of the population migrate to the Bhabar in the winter. Agricultural conditions in the Bhabar depend almost entirely on the possibility of canal-irrigation, and the cultivated land is situated near the mouth of a valley in the hills. Rice is grown in the autumn, and in the spring rape or mustard and wheat are the chief crops. Farther south in the Tarai and in Kashipur cultivation resembles that of the plains generally. In the northern portion the soil is light ; but when it becomes exhausted, cultivation shifts. Lower down clay is found, which is continuously cultivated. Rice is here the chief crop ; but in dry seasons other crops are sown, and the spring harvest becomes more important.

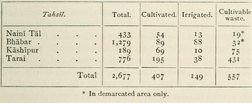

The tenures in the hill tracts have been described in the account of the KuMAUN Division. In the Bhabar the majority of villages are managed as Government estates, the tenants being tenants-at-will and the village managed and the rents collected by a headman. There are also a few villages under zaminddri tenures peculiar to the tract, in which tenants with the khaikari occupancy right of the hills are found. Most of the Tarai is also a Government estate. The cultivators, though mere tenants-at-will, are never dispossessed so long as they pay their rents. In Kashipur the tenures of the plains predominate, but a few villages are managed as Government estates. The main agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are given below, in square miles: —

No crop returns are prepared for the NainI Tal tahsil, in which "wheat, barley, rice, and marud are th? main food-crops, while a little tea and spices are also grown. Rice and wheat are the most important crops in the Tarai and Kashipur, covering loi and 87 square miles respectively, or 38 and 33 per cent, of the net area cropped. Gram, maize, and barley are grown on smaller areas. Oilseeds cover 24 square miles, and a little sugar-cane and cotton are produced. There are five tea estates in the lower hills, but little tea is now made, and fruit-growing is becoming a more important industry. The cultivated area in the hill tracts increased by nearly 50 per cent, between 1872 and 1902 ; but agricultural methods have not improved to any marked extent, except in the extension of irrigation and of potato cultivation. The cultivated area in the Bhabar has also increased, but is entirely dependent on canals. In the Tarai and Kashlpur cultivation fluctuates considerably according to variations in the rainfall. Advances under the Land Improvement and Agriculturists' Loans Acts are small. They are not required in the hills or in the Bhabar.

The hill cattle are smaller than those of the plains; but neither breed is of good quality, though attempts have been made to introduce better strains. Enormous herds are brought from the Districts farther south for pasture during the hot season. Ponies of a small, but hardy, variety are bred in large numbers along the foot of the hills for use as pack-animals. Goats and sheep are of the ordinary type, and con- siderable flocks are driven up in the winter from the plains to the Tarai. In the hills goats are seldom used to supply milk, but are kept for their flesh and manure.

The total area irrigated in 1903-4 was 149 square miles. A few square miles are irrigated in the hills from channels drawn from the rivers and carried along hill-sides, besides irrigation from springs and water near the surface. The greater part of the irrigation in the rest of the District is from small canals. These are drawn in the Bhabar from the rivers which flow down from the hills, supplemented by lakes which have been embanked to hold up more water. Owing to the porous nature of the soil and gravel which make up that area, there is a great loss of water, and the channels are gradually being lined with masonry. More than 200 miles of canals have been built, command- ing an area of no square miles. In the Tarai the small streams which rise as springs near the boundary of the Bhabar were formerly dammed by the people to supply irrigation. Immense swamps were formed and the tract became extremely unhealthy. Canals and drainage systems have, however, been undertaken. The canals are chiefly taken from the small streams and are 'minor' works. In the east the villagers themselves make the dams and channels. The more important canals are divided between the charges of the Engineer attached to the Tarai and Bhabar and of the Engineer of the Rohilkhand Canals.

Forests

The forests of the District cover an area of about 1,510 square miles, of which about 900 are ' reserved ' and 340 consist of ' protected ' forests. They are situated partly in the submontane tract and partly in the hills. In the former tract the most valuable product is sal (Shorea robusta) ; while shisham (Dalbergia Sissoo), haldu (Adina cordifolia), and khair ?(Acacia Catechu) are also found. Sal extends up to about 3,000 feet, and is then replaced by various pines, especially chlr {Pinus longifolia), and ultimately by various kinds of oak (Quercus semecarpifolia, incana, and dilatatd). The whole of the waste land in the hill tracts has now been declared 'protected' forest to prevent further denudation, which had begun to threaten the cultivation in the river-beds. Most of the ' reserved ' forest area is included in the Naini Tal, Kumaun, and Garhwal forest divisions, and accounts are not kept separately for the District. The receipts are, however, large, amounting to 2 or 3 lakhs annually.

The mineral products are various, but have not proved of great value. Building stone is abundant, and lime is manufactured at several places. Iron was worked for a time both by Government and by private enterprise ; but none is extracted now. Copper is also to be found, but is not worked. A little gold is obtained by washing the sands of the Dhela and Phika rivers ; and other minor products are alum, gypsum, and sulphur.

Trade and communications

Cotton cloth of good quality is largely woven in the south-west of the District, especially at Jaspur, and is dyed or printed locally for export to the hills. Elsewhere only the coarsest material is produced for local use. In the hill tracts a coarse kmd of cloth, sackmg, and ropes are woven from goat's hair. There are no other industries of importance. A brewery is situated close to Naini Tal, which employs about 50 hands. The District as a whole imports piece-goods, salt, and metals, while the chief exports are agricultural and forest produce. The hill tracts supply potatoes, chillies, ginger, and forest produce, and import grain from the Bhabar. The surplus products of the latter tract consist of grain, forest produce, and rapeseed. There is little trade to or from the Tarai. A considerable through traffic between the interior of the Himalayas and the plains is of some importance to this District. NainI Tal is the chief mart in the hills, while HaldwanI, Ramnagar, Chorgallia, and KaladhungI in the Bhabar, and Jaspur and Kashlpur are the principal markets in the plains.

The only railway is the Rohilkhand-Kumaun line from Bareilly to Kathgodam at the foot of the hills below NainT Tal ; but extensions are contemplated from Lalkua on this line via Kashlpur to Ramnagar, and from Moradabad on the Oudh and Rohilkhand Railway to Kashl- pur. There are 737 miles of road, of which 173 are metalled and are in charge of the Public Works department. The cost of the metalled roads is charged to Provincial revenues, while 226 miles of unmetalled roads are maintained by the District board, and 337 by the Tarai and Bhabar estate funds. The chief road is that from Bareilly through Kathgodam to Ranikhet and Almora, passing close to NainI Tal. Another road from Moradabad through Kashlpur and Ramnagar also leads to Ranikhet.

Famine

Famine is practically unknown in the District, though high prices cause distress among the lowest classes. A serious failure of rain in the hills has never happened ; and although deficiency injures the crops, the hill people depend largely on the Bhabar, in which irrigation is drawn from permanent sources. The Tarai suffers more from excessive rain than from drought, and the canal system protects every part of the low country except Kashl- pur, where scarcity was experienced in 1896.

Administration

The District is in charge of a Deputy-Commissioner, who is ordinarily assisted by a member of the Indian Civil Service and by a Deputy- Administration. Collector, who are stationed at NainI Tal. The KashTpur tahs'il forms a subdivision in charge of another Deputy-Collector, who resides at Kashlpur except during the rains. A special superintendent manages the Tarai and Bhabar Government estates. A tahsildar is stationed at the head-quarters of each tahsil except Nairn Tal and Kashlpur, where there is a naib-tahsilddr. In addition to the ordinary District staff, an Engineer is in charge of canals and other public works in the Government estates, and the forests are divided between several forest divisions.

Naini Tal is administered as a non-regulation tract, and the same officers exercise civil, revenue, and criminal jurisdiction. In civil matters the Commissioner of Kumaun sits as a High Court, while the Deputy-Commissioner has powers of a District Judge, and his assistants and the tahsilddrs have civil powers for the trial of suits. The Com- j

missioner is also Sessions Judge in subordination to the High Court at Allahabad. There is little crime in the hill tracts ; but dacoity is fairly common in the Tarai and Bhabar, and this is the most serious form of crime. The proximity of the State of Rampur favours the escape of criminals. •

A District of NainI Tal was first formed in 1891. Before that date the hill tracts and the Bhabar had been included in what was then the Kumaun, but is now called the Almora District. The parganas included in Kashlpur and the Tarai were for long administered as parts of the adjoining Districts of Moradabad and Bareilly. About 1861, after many changes, a Tarai District was formed, to which in 1870 Kashlpur was added. The tract was at the same time placed under the Commissioner of Kumaun.

The first settlement of the hill tracts and the Bhabar in 1815 was based on the demands of the Gurkhas and amounted to Rs. 17,000, the demand being levied by parganas or pattls (a subdivision of the pargana), and not by villages, and being collected through headmen. Short-term settlements were made at various dates, in which the revenue fixed for each paill was distributed over villages by the zafntnddrs themselves. The first regular settlement was carried out between 1842 and 1846, and this was for the first time preceded by a partial survey where boundary disputes had occurred, and by the preparation of a record-of-rights. The revenue so fixed amounted to Rs. 36,000. A revision was carried out between 1863 and 1873 ; but the manage- ment of the Bhabar had by this time been separated from that of the hills. In the latter a more detailed survey was made. Settlement opera- tions in the hills differ from those in the plains, as competition rents are non-existent. The valuation is made by classifying soil, and esti- mating the produce of each class. The revenue fixed in the hill pattls alone amounted to Rs. 34,900, which was raised to Rs. 50,300 at the latest assessment made between 1900 and 1902. The latter figure includes the rent of potato clearings, which are treated as a Government estate, and also revenue which has been 'assigned,' the actual sum payable to Government being Rs. 43,100. There was for many years very little advance in cultivation in the Bhabar, the revenue from which in 1843 was only Rs. 12,700. In 1850 it was placed in charge of Captain (afterwards Sir Henry) Ramsay, who was empowered to spend any surplus above the fixed revenue on improving the estate. The receipts at once increased by leaps and bounds, as irrigation was provided and other improvements were made. Revenue continued to be assessed as in the hills in the old settled villages, while the new cultivation was treated as a Government estate. The first revision in 1864 yielded Rs. 60,000, of which Rs. 4,000 represented rent; and the total receipts rose to a lakh in 1869, 1-4 lakhs in 1879, nearly 2 lakhs in 1889, and 2-4 lakhs in 1903. Of the latter figure, Rs. 57,000 is assessed as revenue and Rs. 1,85,000 as rent. The greater part of the Tarai is held as a Government estate, and its fiscal history is extremely complicated, as portions of it were for long administered as part of the adjacent Districts. The land revenue in 1885 amounted to Rs. 70,000 and the rental demand to about 2 lakhs. The latter item was revised in 1895, when rents were equalized, and the rental demand is now about 2-5 lakhs. Kashlpur was settled as part of Moradabad District, and at the revisions of 1843 and 1879 the revenue demand was about a lakh. A revision has recently been made. The total demand for revenue and rent in Nainl Tal District is thus about 7 lakhs. The gross revenue is included in that of the Kumaun Division.

There are two municipalities, Kashipur and Naini Tal, and one ' notified area,' HaldwanT, and four towns are administered under Act XX of 1856. Beyond the limits of these, local affairs are managed by the District board; but a considerable expenditure on roads, education, and hospitals is incurred in the Government estates from Provincial revenues. The District board had in 1903-4 an income of Rs. 37,000 and an expenditure of Rs. 82,000, including Rs. 42,000 spent on roads and buildings.

The Superintendent of police and a single circle inspector are in charge of the whole of the Kumaun Division. In the hill tract of this District there are no regular police, except in the town of Nairn Tal and at three outposts, the duties of the police being discharged by the pativdris, who have a higher position than in the plains. There is one reserve inspector; and the force includes 37 subordinate officers and 135 constables, besides 83 municipal and town police, and 152 rural and road police. The number of police stations is 11. A jail has recently been built at HaldwanT.

The population of NainI Tal District is above the average as re- gards literacy, and 4*2 per cent. (7-1 males and 0-5 females) could read and write in 1901. The Musalmans are especially backward, only 2 per cent, of these being literate. In 1 880-1 there were only 16 public schools with 427 pupils; but after the formation of the new District education was rapidly pushed on, and by 1900-1 the number of schools had risen to 60 with 1,326 pupils. In 1903-4 there were 93 public schools with 2,277 pupils, including 82 girls, besides 13 private schools with 170 pupils. Only 200 pupils in public and private schools were in advanced classes. Two schools were managed by Government and 77 by the District and municipal boards. The expenditure on educa- tion was Rs. 1 2,000, provided almost entirely from Local and Provincial funds. These figures do not include the nine European schools in Naini Tal Town, which contain about 350 boys and 250 girls.

There are 14 hospitals and dispensaries in the District, with accom- modation for 104 in-patients. In 1903 the number of cases treated was 78,000, of whom 1,040 were in-patients, and 1,687 operations were performed. The expenditure amounted to Rs. 49,000. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 11,000, giving an average of 37 per 1,000.

[J. E. Goudge, Settlement Report, Almord and Hill Pattls of Nairn Tdl (1903) ; H. R. Nevill, District Gazetteer (1904).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.