Kayastha, Kayath, Kait

(Created page with "This article is an extract from {| class="wikitable" |- |colspan="0"|<div style="font-size:100%"> '''THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL.''' <br/> By H.H. RISLEY,<br/> INDIAN C...") |

(→Kayastha, Kayath, Kait) |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

The following is a list of the gotras of the Kulin and Madhalya Kayaths, but the correct order of precedence is a subject of interminable dispute and heart-burning:� | The following is a list of the gotras of the Kulin and Madhalya Kayaths, but the correct order of precedence is a subject of interminable dispute and heart-burning:� | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:K K.png||frame|500px]] |

[[File:KK1.png||frame|500px]] | [[File:KK1.png||frame|500px]] | ||

The four families next in order are designated Maha-patra:� | The four families next in order are designated Maha-patra:� | ||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

''1 Mr. J.D. Ward, C.S. suggests the following reading and interpretation: Pura (full), jana, or gana, daha (ten), masha. Each rupee was to value ten full machas. A "masha" equalled 17 3/8 grains, and a rupee ten mashas.'' | ''1 Mr. J.D. Ward, C.S. suggests the following reading and interpretation: Pura (full), jana, or gana, daha (ten), masha. Each rupee was to value ten full machas. A "masha" equalled 17 3/8 grains, and a rupee ten mashas.'' | ||

| + | |||

=Notes= | =Notes= | ||

Latest revision as of 12:29, 29 November 2017

This article is an extract from

THE TRIBES and CASTES of BENGAL. Ethnographic Glossary. Printed at the Bengal Secretariat Press. 1891. . |

NOTE 1: Indpaedia neither agrees nor disagrees with the contents of this article. Readers who wish to add fresh information can create a Part II of this article. The general rule is that if we have nothing nice to say about communities other than our own it is best to say nothing at all.

NOTE 2: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a very old book. Therefore, footnotes have got inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. Readers who spot scanning errors are requested to report the correct spelling to the Facebook page, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be duly acknowledged.

[edit] Kayastha, Kayath, Kait

The origin of this important caste is unknown, and all attempts to explain how and when it rose have been fruitless. In one part of the country the members claim to be of higher rank than the Sudras, and repudiate that title; but in Bengal they are classified immediately below the Baidya caste, with whom they live on terms of great jealousy. If we accept Karana,1 which means "a man of mixed race," as synonymous with Kayath, the caste is descended from a Brahman father and a mother of the class next beneath it in rank; but according to other authorities it is the issue of a Kshetriya father and a Vaisya mother. The Kaits, however, are better pleased to have their parentage doubtful than to be the reputed offspring of such an ignoble stock.

The word Kayath is generally derived from the Sanskrit Kaya, a body, because the progenitor of the clan is said to have sprang from the body of Brahma, yet it is probable that Kayath was simply a man's and not a tribal name.

The Kayaths of Bengal are believed to be descended from five persons who served the five Brahmans brought from Kanauj by Adisura in the ninth century. The names of the five servants were�

Dasaratha Bosu, Kali Das Mittra,

Makaranda Ghose, Purushottama Datta.

Virata, or Sukdeo Guha, A tradition survives, that after celebrating the "Putreshti Jagya," for which their masters had been summoned, the Kayaths returned to Kanauj, but were repudiated as outcasts by their brethren, upon which they came back to Bengal with two other members of their clan, named Nag and Nath, and settled at Pancha-Sara in Bikrampur.

The Kayaths of Bengal are subdivided into four great tribes, who formerly had no connection with one another, although all were engaged in the same profession, but of late years the causes of separation having been removed, individuals belonging to allied tribes intermarry.

The four tribes are�

Uttar Rarh, Bangaja,

Dakhin-Rarhi, Varendra.

The distribution of the tribes is as follows:�

The Uttar-Rarhi are met with in the districts of Birbhum, Burdwan, Murshidabad, parts of Rangpur, Dinajpur, Hughli, and Jessore. The Dakhin-Rarhi are massed in Burdwan,Hughli, Midnapur, 24 Pergunnahs, Jessore, Kishnaghur, and parts of Baqirganj, while in Dacca only two families reside. The Bangaja are established in Baqirganj, Jessore, 24 Pergunnahs, Dacca, Farridpur, western part of Mymensingh, eastern part of Pubna, and in several villages of the Bograh district. The Varendra are settled in Rajshahi, Pubna, Maldah, bograh, Dinajpur, as well as here and there throughout Farridpur, Jessore, and Kishnaghur.

The second and third tribes are so closely allied that the same gotras are common to both, and of late years they have been fast amalgamating: but the first and fourth, having no Kulins, are more conservative of old party customs. In Eastern Bengal the Bangaja tribe includes nine-tenths of the whole Kayath caste, while the remainder belong to the Dakhin Rarhi. The following remarks will therefore be confined to the former.

The Bangaja Kayaths have Ghataks of their own, residing at Edilpur, in Baqirganj, from whom the account of the various subdivisions has been obtained. The Ghatak registers go back twenty-three generations, to the fourteenth century, when the Muhammadans had conquered the most important part of Bengal. It is probable, however, that the occurrences of a later age have been embellished by the traditions of an earlier, and that the present organisation of this great tribe was the work of a reformer who lived long after the reigns of Adisura and Ballal Sen. Whoever reorganised the tribe, he gave the rank of Kulin to the four families of�

Vasu or Bosu, Guha,

Ghosa, Mittra; while to Datta, who was of a proud and independent spirit, refusing to be the slave of any Brahman, was allotted only a half Kul. On the other hand, Dutt, Nag, Nath, and a family of bondsmen, called Dasa, were enrolled as Madhalya, or intermediate, Kayaths, with whom the Kulins may marry without loss of rank.

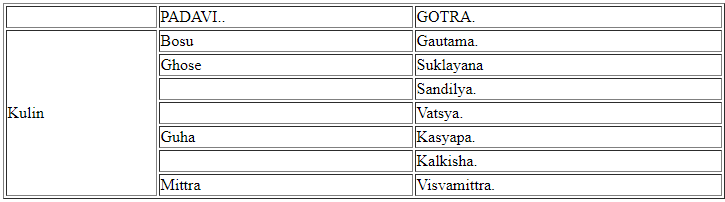

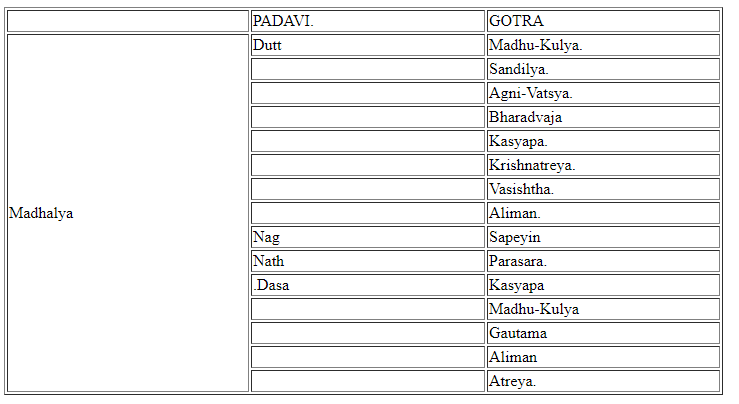

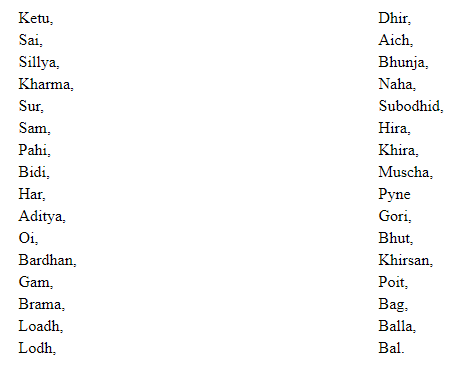

The following is a list of the gotras of the Kulin and Madhalya Kayaths, but the correct order of precedence is a subject of interminable dispute and heart-burning:�

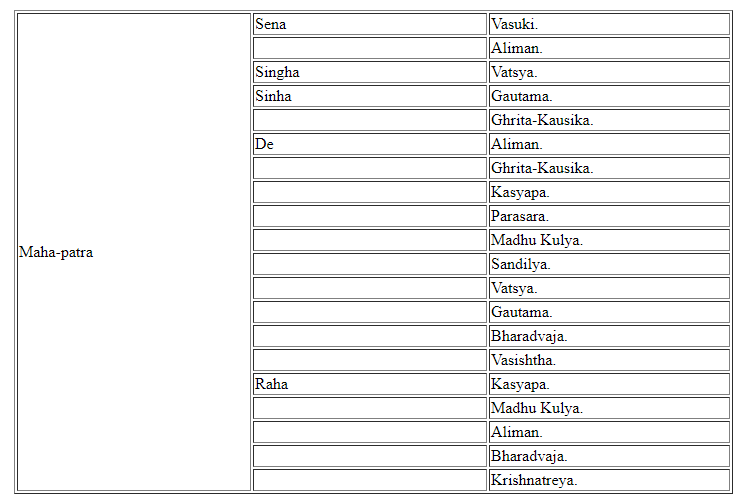

The four families next in order are designated Maha-patra:�

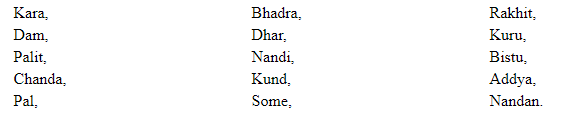

Next below these are fifteen families, who by giving their daughters in marriage to Kulins, can raise themselves to the grade of Maha-patra, but a marriage of this nature brings a certain amount of discredit on the family of the bridegroom. The fifteen are�

Their gotras, being the same as those of the higher grades, do not require mention.

Regarding the still lower grades, different lists and names are given. According to some, they number seventy-two, but the "Samaj," or council of the Bangaja, only recognise thirty-two, while the larger number is met with among the Dakhin Rarhi Kayaths. The thirty-two grades are of very low birth, and Kulins who intermarry with them lose much, if not all, of their family prestige. The following names are not often met with nowadays, but a few are familiar to residents:�

1 In Midnapore Kayasths still describe themselves as Karana.

The higher grades of Kayaths will only eat with these when paid for so doing. Many of them are writers and educated men, but others are poor and illiterate peasants.

According to the census returns the Kayath caste numbers 1,160,478 individuals, a large proportion of whom are residents of the nine districts of Eastern Bengal. It is likewise remarkable that they are most numerous in Bqirganj (125,164), Mymensingh (105,537), Dacca (102,084), and Midnapore (101,663) districts, on the outer borders of the province, a circumstance that either indicates a descent from mixed races, or a special aptitude for development on the confines of advancing civilization. It must, however, be borne in mind that the term Kayath is often used by the lower classes of Bengal as the equivalent of Sudra.

The Kayath caste is the most intellectual, and best educated in Bengal. Although of doubtful parentage it has from the earliest historical period been an ambitious and prosperous community, which even under Muhammadan rule held most of the financial and revenue appointments throughout India; and since the English occupation of the country has almost secured the whole of the subordinate Government offices. At present. they are as skilful penmen, and as good English scholars as they were formerly Persian. Furthermore, there is perhaps more of a clannish spirit among them than among any other caste of Bengal.

Sir George Campbell describes the Kayaths as "decidedly dark, generally thin, spare men, and on the average short, with often sharp weasel-like features, small and quite low-Aryan." In Dacca the Kayaths are of a deeper brown colour than the Kulin Brahmans, but every shade of brown may be met with. Some are large powerful men, but after thirty-five they become fat and sleek-headed, and generally indolent. Their undoubted talents are too often expended on chicanery and legal quibbles, and it is very rare to find in Eastern Bengal any highly educated men who love literature for its own sake, not for the favours it bestows. It may be safely said, that every Kayath can read and write Bengali, that a large majority are well versed in English, as taught in the schools, and that a few are acquainted with Sanskrit. It is, however, very seldom that a Kayath is found who can read Persian, as that language is deemed of little value by the Hindus of Bengal, and it is rare indeed for a Hindu boy to attend the Persian class at college.

It is a melancholy fact that this clever and rising caste should always have been extravagant and dissipated. None of the large Zamindars of Eastern Bengal are Kayaths, and few families are, as regards wealth, on an equality with the Brahman and Baidya houses. Many reasons are given in explanation of this anomaly. Kayaths held almost all the lucrative posts under the Muhammadan rulers of Bengal, were farmers of the revenue, and were not often credited with tender feelings or conscientious doubts. As was said of them by a Muhammadan, who knew them well, they were like a sponge, imbibing what they could on all occasions, but parting with their plunder as readily as it does when squeezed. Whenever a revenue officer was reported to have accumulated wealth, he received a summons to Murshidabad, and was compelled to give up all that he had, or become a Muhammadan. In former days, moreover, the rank of a Kayath depended much on the number of slaves he retained, and wonderful stories are told of the swarms of dependants belonging to the old families. Their marriage ceremonies, likewise, and their religious rites, have always been accompanied by more ostentation and lavish expenditure than with other castes. Dissolute and intemperate habits were natural consequences of an uncertain position. Rich to-day, they, might be beggars to-morrow, and the savings of years might be swept away by a word from the Nawab. But, even after a century of peace and security, the Kayaths are the same improvident people they were under the Mughal dynasty.

The Sakta worship generates drunkards, and no one can be a devoted worshipper without drinking spirits to a fearful extent. While the doctrines of Chaitanya have united almost all the artisan and agricultural castes in a common faith, the immoral Sakta ritual is observed by the three highest and most intelligent of the Hindu castes, namely, the Brahman, Baidya, and Kayath. All Kulin Kayaths, and three-fourths of the other subdivisions, follow the Sakta worship, and one-half of these celebrate the "Vahmachari Achar," or Chakra rites. By this, intoxication is legalised and made a religious duty, while obscenity is countenanced and enforced. English education has not as yet reformed them, and probably at no former period was intoxication so universal and habitual as at the present day.

These strictures, true of the caste collectively, are unjust towards many of the most philanthropic and excellent native gentlemen to be met with in Bengal, who lament the degradation of their brethren, and do their utmost to stem the torrent of unbelief and immorality which is destroying the noblest qualities of their countrymen. As yet their endeavours have proved ineffectual, but it is for the rising generation to realize their position, to denounce the vices of their brethren, and to assume the lead in the advancement and in the civilization of their countrymen.

A Kulin Kayath family is almost as exclusive as that of a Kulin Brahman, and it is equally dependent on the Ghatak for the preservation of its station and purity. A member of this class can only retain his rank by marrying the daughter of a Kulin, or by giving his son or daughter in marriage to a Kulin family. Should any family during three generations neglect to form an alliance with another Kulin family its patrician dignity is lost: but a single, or even a second, mesalliance does not lower the credit of the house. Families who have always intermarried with Kulins are called "Ganga-tirtha" Kulins, being regarded as the purest.

When a Kulin Kayath is degraded, he never can regain the position he has lost, but his descendants, by marrying Kulins, thenceforward become known as "Kulaja." Finally, should a Kulin marry a daughter of the Kulaja or Madhalya classes, he continues to preserve his respectability. This union is called "Visrama-sthan." Adopted children, moreover, do not acquire the position of the person adopting them.

Like other clean Sudra castes who follow the Sakta ritual, the Kulin Kayath has a private temple, or sacred nook, where a Siva-linga is erected, and daily worship performed by the head of the household. All Kayaths, except those of the Vaishnava sect, observe the Sri Panchami, or "Dawat Pujah," on the fifth of the waxing moon in Magh (January-February). This festival is held in honour of Sarasvati, the goddess of learning, who, strange to say, is regarded by both Kayaths and prostitutes as their patron deity. On this day the courts and all offices are closed, as no Hindu penman will use pen and ink, or any writing instrument, except a pencil, on that day. When work is resumed a new inkstand and pen must be used, and the penman must write nothing until he has several times transcribed the name of the goddess Durga, with which all Hindu epistolary correspondence begins. Kayaths are expected to spend the holiday in meditating on the goddess Sarasvati after they have observed certain religious rites, and sacrificed a kid to Kali or Durga; but in reality they spend it in immorality and dissipation, for which reasons the "goddess of learning " has in some way come to be regarded as the tutelary deity of the "Peshahgar." On this day the Kayath must taste of a Hilsa fish, whatever its price, while from the Sri Panchami festival in January to the Vijaya Dasami in September or October, fish must be eaten daily; but from the last to the first month it must not be touched. This curious custom, probably founded on some hygienic superstition, is often reversed by Bengali Kayaths.

As much as a thousand, and occasionally two thousand, rupees are paid by a bride's father to a Kulin Kayath at his marriage, but formerly either fourteen or twenty-one rupees were the recognised sums given, and even now, the formality is gone through of asking the bride's father if he has received that amount, although it is not the custom to accept it. In old families the Purohit officiates at the marriage service, and before ir a fast is observed, during which Kali is worshipped.

The chief strength of the Brahmo Samaj lies in the ranks of the Kayaths, and every Kayath boy attending the Government college becomes a member of this new sect. These boys are necessarily outcasted, and unless their parents cease to associate with them, expulsion befalls the whole family. On returning home a Brahmo boy is not permitted to enter his father's house, but is fed and entertained by himself in an outhouse. In Dacca a few Brahmo households exist, the males and females of which have become Brahmos and Brahmikas, but a few faint-hearted individuals, Brahmos in Dacca, are Hindus at their homes. There is reason for anticipating that the whole caste will very soon become Brahmos. The Kayaths have time on their side, and are confident that Brahmoism is the destined religion of the Hindus, and that the Crescent will go down before the hosts of Deism. Great rejoicings were lately made on the occasion of the conversion of Zahiruddin of Sunnargaon, a student of the Dacca college. He was secretly made a Brahmo, and named Jai Narayana. Subsequently he became a "Prakash," or perfect Brahmo, receiving the title of Jala Dhar Babu, which entitled him to eat and drink with the Kayaths.

Throughout the eastern districts of Bengal there is a very numerous body of natives called Ghulam, or slave, Kayaths, and also known as Shiqdar, or Bhandari. Their existence as an adjunct, or graft, of the Kayath stock is both interesting and peculiar, and would appear to explain the obscure and hetero-geueous character of the main stem. The Ghulam Kayaths are descended from individuals belonging to clean Sudra castes, who sold themselves, or were sold, as slaves to Kayath masters. It is stoutly denied that anyone belonging to an unclean tribe was ever purchased as a slave, yet it is hard to believe that this never occurred. The physique of the low and impure races has always been better than that of the pure, and on account of their poverty and low standing a slave could at any time be more easily purchased from amongst them. However this may be, it is an undoubted fact that any Ghulam Kayath could, and can, even at the present day, if rich and provident, raise himself by intermarriage as high as the Madhalya grade, and obtain admission among the "Bhadra-lok," or gentry of his countrymen.

For the following translation of a deed of sale I am indebted to the late Babu Brijo Sundar Mittra, a scion of one of the oldest and most respected Kayath families of Dacca:�

"I, Ram Kisto Pal, son of Tula Ram Pal, and grandson of Ram Deva Pal, do hereby execute this deed of sale.

"Owing to the debts incurred at my marriage, and which I am unable to pay, I, in my proper mind, and of my own free will, sell myself to you on my receiving a sum of Purojonodoho-masi1 rupees twenty-five, and I and my descendants will serve you as slaves as long as we are given subsistence allowance and clothing, you, your sons, and grandsons shall make us work as slaves, and have power to sell, or make a gift of us to others. On these conditions I execute this bond.

"Dated 19th Kartik, 1201 B.S. (November, 1794)."

Although slavery is illegal, and has been so for many years, the buying and selling of domestic slaves still goes on, and it may be safely said that there is hardly a family of any distinction which has not several Bhandaris on its establishment. The life of the Nafr, or Shahna, as the slave is called in other parts of the country, is most congenial to the Bengali. With rare exceptions he is kindly treated, and in return he regards the welfare and happiness of each member of the family as inseparable from his own. Owing to the deaths of their masters many thousands are scattered throughout Bengal, who are found working at all trades, and do not consider themselves degraded by holding a plough or wielding a mattock. In Bikrampur they are often boatmen, while in Dacca Kayaths are employed as confectioners, coolies, brasiers, shopkeepers, and venders of Pan and Indian hemp.

Brahmans, Baidyas, Sahas, and Banyas possess slaves, but none of these castes have ever permitted their servants to rise in rank, or assume an equality with their masters. It is suggested by the Kayaths that the Ghulam Kayaths of the present day are the descendants of the tribe resident in Bengal before the advent of the Kanauj families; but this conjecture is erroneous, for not only are individuals being added even now to the servile branch, but admissions such as that of Ram Kisto Pal, the subject of the deed of sale (who was a Teli by caste), can be proved by existing documents.

The honorary titles borne by the Kayath families are numerous. The most common are Biswas, Bhumika, Dhali, Majumdar, Qanungo, Mahalla-nawiz, Pattadar, Shiqdar, Niyogi, Mustaufi, and Mushrif. Besides these official distinctions, the Rajas of Chandradwip conferred others, such as Dasta-dar, Thakurta, and Muncif, which are borne by Guha and Ghose families at the present day, From these titles we learn that formerly the Bengali Kayath wielded other weapons than the pen, and that while some fought in the ranks as shield-bearing (Dhali) soldiers, others commanded as brigadiers (Dastadar).

In olden times the most famous Kayath family in Bengal was the "Banga Adhikari," which gave for many generations the Qanungoes, or finance ministers, to the province. Their residence was in Dacca so long as the seat of government was there, and a bazar near their mansion is still named Rai Bazar. A private idol, known as Sama Rai, has for two centuries been maintained by the rent of a piece of land. Early in the eighteenth century the family removed to Murshidabad, where its representatives still reside.

The leading Kulin Kayath family of Dacca is the family of Bose, or, as they prefer calling themselves, Bose-Thakurs, of Bose-nagar in Bikrampur. The founder of the house was Devi Das Bose, Qanungo of the Nawarah Mahall, whose Muharrir, or clerk, was Krishna Jivana Majumdar, father of the celebrated Rajah Raj Bullabh. An old building at Bose-nagar still bears an inscription put up by the builder, Devi Das, with the date A.H. 1087 (1676).1

The oldest and most respected house among the Bangaja Kayaths, however, is that of Chandradwip. For seventeen generations the family has dwelt in Baqirganj, and its head has always been the Samaj-pati or president of the caste.2

1 Mr. J.D. Ward, C.S. suggests the following reading and interpretation: Pura (full), jana, or gana, daha (ten), masha. Each rupee was to value ten full machas. A "masha" equalled 17 3/8 grains, and a rupee ten mashas.