Karnataka: caste, mutts and elections

(→Its importance; voting pattern in 2008, 2013, 2014) |

m (Pdewan moved page Karnataka: caste and elections to Karnataka: caste, mutts and elections without leaving a redirect) |

Revision as of 11:29, 10 May 2018

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The district-wise distribution of castes

The main castes, their districts

The caste vocabulary of Karnataka politics, May 5, 2013: India Today

Lingayats and Vokkaligas are the two major caste groups in the state that have dominated the political scene for decades.

Lingayats, Vokkalikga heartland, Old Mysore, Hyderabad-Karnataka, Mumbai-Karnataka: These terms crop up frequently in the media as voters in Karnataka queue up to cast their votes Sunday to elect the state's 14th assembly.

To explain some frequently used terms: Lingayats and Vokkaligas are the two major caste groups in the state that have dominated the political scene for decades.

Lingayats: The largest community in Karnataka, born out of the reform movement of 12th century saint Basavanna, spread all over the state, and are dominant in the northern part. Lingayats worship Hindu god Shiva, and traditionally engage in agriculture and business.

As a group, the voting pattern of the Lingayats will be keenly analysed as B.S. Yeddyurappa, a Lingayat credited with rallying the community behind the BJP and bringing that party to power in the state for the first time in any southern state in 2008, has since left it. He now heads the Karnataka Janata Party (KJP) and says his main aim is to root out the BJP from the state.

Vokkaligas: A major land-owning community dominant in south Karnataka, which is also believed to be the stronghold of the Janata Dal-Secular (JDS), as it is headed by former prime minister H.D. Deve Gowda, a Vokkaliga.

The battle for Vokkaliga votes is mainly between JDS and the Congress, though BJP has been trying to get rid of the image that it depends mostly on Lingayats for support.

Kurubas (shepherds community): This group is spread all over Karnataka, and reference to this group will be mainly because Congress leader Siddaramaiah, who is a Kuruba, is a chief ministerial aspirant.

There are parts of the state known as Hyderabad-Karnataka, Mumbai-Karnataka -- because these were parts of those regions until states' reorganization in 1956 on language basis.

Old Mysore region: The reference is to a major part of south Karnataka. The name Karnataka came into being in the early 1970s. Till then, the state was known as Mysore.

The name change followed years of demands following the reorganization of states in 1956, integrating a large part of Kannada-speaking areas in the northern part with Mysore.

Hyderabad-Karnataka: The reference to the districts of Bellary, Raichur, Gulbarga, Koppal, Bidar and Yadgir in the north, which were part of Hyderabad province during the rule of the Nizams.

Mumbai-Karnataka: This reference is to Belgaum, Dharwad and surrounding areas in the north which were part of Bombay presidency during pre-Independence days.

Coastal Karnataka: Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Uttara Kannada, on the west coast. This region had become a BJP stronghold, but the influence of that party waned in municipal polls in March this year. The BJP fared poorly in those polls.

A district-wise survey of caste-consciousness

ND Shiva Kumar & Narayanan Krishnaswami

They will caste their vote: Karnataka still remains extremely caste-conscious

The Times of India, Apr 29, 2013

The The Times of India-Daksh survey examines the importance of caste as an influence on voting behaviour and comes up with some surprising findings about voter attitudes in Karnataka.

The tie is caste. For all its tech-savvy and progressivism, Karnataka still remains extremely caste-conscious when it comes to the ballot box. According to the ToI-Daksh survey of 10,772 voters across the state, 41% of respondents believe caste is very important in deciding who to vote for. The candidate comes a poor second: around 20% of prospective voters cite that the person they are voting for matters most.

The survey found Dharwad, Gadag, Chitradurga and Haveri districts much more caste-conscious than the coastal or Hyderabad-Karnatak regions. Fully, 97% of the survey's respondents from Dharwad pronounce caste as the most important factor when it comes to choosing a candidate. Nearly 88% of respondents from Gadag, 76% from Chitradurga and 70% from Haveri are caste-conscious. On the other side of the spectrum, Udupi, Kodagu and Dakshina Kannada districts show fewer than 1% of respondents believing caste is important.

When asked about the range of opinions uncovered by the poll, political analyst and pro-vice-chancellor of Jain University Sandeep Shastri explains: "Normally, if the values are 0% or more than 90%, it's a bit surprising. However, there is indeed a higher level of caste consciousness in Dharwad, Gadag and Chitradurga districts, the stronghold of the Lingayats. There is always a strong caste-based mobilization in these districts. As far as Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Kodagu are concerned... the caste factor in polls is indeed less." The survey also shows increased caste-based voting among older voters. Half the respondents over the age of 61 say caste matters to them. Unsurprisingly, younger voters are more progressive; 46% of voters below the age of 45 gave minimal importance to caste.

The real shocker is that the highest educated demographic also shows the most caste sensitivity; 47% of respondents with postgraduate education say they are influenced by caste. On the other hand, only 39% of uneducated voters say caste matters to them.

"It is not surprising," says R Indira, a sociologist at Mysore University. "A person's first identity factor is caste. It was believed that the influence of caste would diminish with education. But education does not necessarily mean a change of heart. Now caste polarization is taking place in new ways. Up till the 1980s, people felt embarrassed to openly speak about caste. Now, it is being discussed in the open. The proliferation of caste- and subcaste-based organizations and the increase in the number of caste-based mutts have played a major role in making people aware of caste."

Nearly 43% of rural voters are likely to vote by caste, as opposed to 38% of urban voters. Men seem more caste-conscious, with 43% rating caste highly, as against 37% of women.

In terms of income, the segment with annual incomes between Rs 1 lakh and Rs 10 lakh are the most likely to vote on the basis of caste. Those with incomes between Rs 25,000 and Rs 50,000 are the least likely to take caste into consideration when voting.

Political parties are all too aware of this. Caste calculus underlies seat allocation and candidate selection. The dominant Lingayat and Vokkaliga communities have the lion's share of party tickets. Lingayat strongman BSY has allocated 71 tickets to fellow Lingayats. Close behind is the BJP which has given 60 tickets to Lingayats. The JD(S) plays for the Vokkaliga vote, with 56 tickets allocated to the community. The Congres targets the backwards communities, with 48 tickets given to members of the backward castes. Clearly, caste makes political sense.

(Story by ND Shiva Kumar & Narayanan Krishnaswami; Survey by Harish Narasappa & Kishore Mandyam)

OBCs

Smaller OBC votes can swing battles in K'taka

From: ManuAiyappa Kanathanda, How smaller OBC votes can swing big battles, April 28, 2018: The Times of India

Small is big for Karnataka polls as winning margins become increasingly slender. It explains parties’ focus on 200-odd smaller castes within Other Backward Classes (OBCs) that could make a difference in several seats.

In fact, the ‘other’ OBCs were key to the rise of Siddaramaiah as an Ahinda leader. OBCs in Karnataka are a motley category of 207 castes, including Vokkaligas, Kurubas and the OBC section of the numerically dominant Lingayats.

‘Other’ OBCs may not be individually significant but together make up a crucial chunk of votes. The Idigas, Nekaras, Vishwakarmas, Gollas, Upparas, Madivalas, Kumabaras, Tigalas, Savitas, Marathas, Kolis, Namdhari Reddys, Bunts and Kodavas are prominent among them.

“The smaller OBCs have voted differently in each assembly poll; so, it is difficult to predict their thinking,” says N Shankaranna, a backward class leader.

Idigas hold the key in several Dakshina Kannada, Shivamogga and Kalaburagi seats while Nekaras are significant in the north.

With all three parties enjoying the support of dominant castes, the votes of the numerically smaller groups will come into play, added Shankaranna.

Representation of castes in the legislature

2013: Assembly has 103 Vokkaligas and Lingayats

Rishikesh Bahadur Desai, ‘Upper caste’ men still dominate the House, May 14, 2013: The Hindu

As the new government takes over and there are high expectations of “change” on several fronts, a sobering reminder of some things that remain constant is the composition of the Assembly in terms of caste, religion and gender.

Dominant castes in the State — Vokkaligas, Brahmins and Lingayats — which are socially and economically strong and have traditionally enjoyed high representation in the Assembly, continue to have a big presence this time too.

Way higher

For instance, the estimated population of two dominant communities — Lingayats and Vokkaligas — is 15 per cent and 12 per cent respectively (an aggregated average of percentages presented by four backward class commissions so far). Together, they form 27 per cent of the population and by the logic of proportional representation, the Assembly should have 60 members from the two communities. However, the present Assembly has 103 from the two communities (53 Vokkaligas and 50 Lingayats).

There are 11 Brahmins too in the present Assembly, which is, proportionally, nearly double their estimated population size.

2.6 per cent women

And, while there is endless talk on 33 per cent representation for women, the present Assembly of 223 has merely six women, making up 2.6 per cent. None of the political parties can claim to have given good representation to women while giving ticket.

Minorities

The trend of under representation of minorities continues, even though their representation has increased marginally over the last polls.

This House will have 16 members from minority communities (11 Muslims, three Jains and two Christians). The last House had 13 minority members, with nine Muslims, two Jains and two Christians (one nominated member).

“If the minorities are to be represented in proportion to their population, there have to be a minimum of 36 minority members in the House,” said Khaji Arshed Ali, former MLC and editor of Bidar Ki Awaaz Hindi daily and author of Karnataka Muslims and Electoral Politics. According to the Union Government’s status of minorities report, Karnataka has a little over 12 per cent Muslims and another six per cent of other minorities, he said.

“It is not that problems faced by Muslims in a constituency will be solved if a Muslim gets elected from there,” says Syed Tanveer Ahmed, editor of the magazine Karnataka Muslims. The argument, however, is for a fairer representation to all communities in legislature and distribution of political power.

In the 14 Assembly elections till now, Muslim representation has been between 2 and 5 per cent. The highest number of Muslims (17) entered the Assembly in 1978 but there were only two members in the 1983 Assembly.

The Scheduled Caste vote

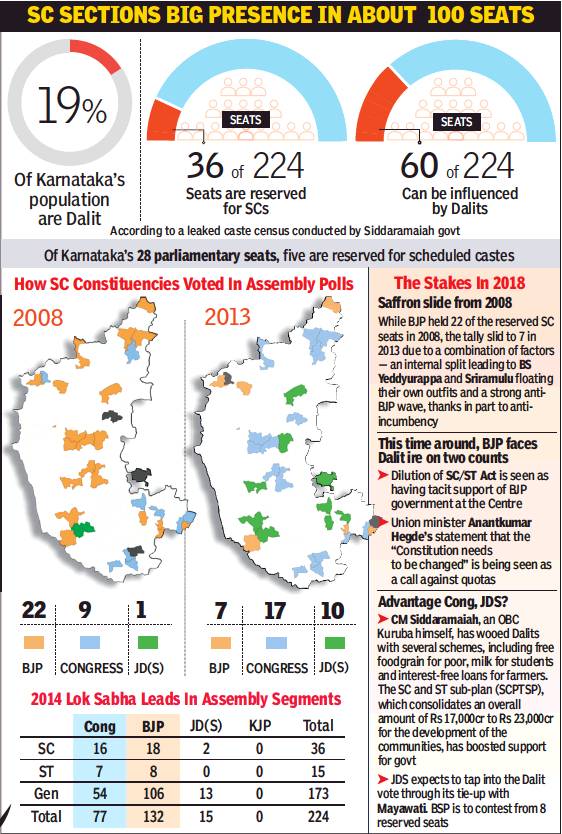

Its importance; voting pattern in 2008, 2013, 2014

SC, ST and ‘general’ voting patterns in 2008, 2013, 2014

From: ManuAiyappa Kanathanda, Why Cong, BJP face an uphill task to win over divided Dalits, April 23, 2018: The Times of India

Wooing the Dalit votebank is among the priorities for the main rivals in the Karnataka polls and, it would appear, with good reason: they make up about 20% of the state’s population and can drive the result in about 100 seats, of which 36 are reserved for SCs.

But it is unlikely that Dalit votes would go en bloc to any one party as the trend in recent times is of the community’s votes getting divided, something that can be explained by the categorisation of the community in the state into so-called ‘untouchable’ Dalits (Madigas) and others (Holeyas). While the Holeyas and similar Dalit groups — Congress veteran Mallikarjuna Kharge represents this category — are seen to be behind Congress, the Madigas, angry at the non-implementation of the Justice A J Sadashiva Commission report on internal reservation, are said to be supporting BJP. Some have even joined JD(S) or BSP.

The Centre for Studies of Developing Societies (CSDS) says that about 50% of the Dalit votes in the past used to go to Congress while BJP’s share was only 20%. But a change was seen in the 2008 state polls when BJP won 22 of the 36 seats reserved for SCs. Later, after Congress managed to bounce back in the 2013 assembly polls, winning 17 of the reserved seats, the trend of Dalit votes getting divided became the new normal.

The Justice Sadashiva Commission, which studied methods of equitable distribution of reservation facilities among SCs, recommended reservation by broadly reclassifying all 101 Dalit groups in the state into four sections. Of the 15% reservation provided for SCs, it recommended 6% to the so-called ‘untouchable’ groups, 5% to the other groups, 3% to ‘nonuntouchables’ and 1% to other SC groups.

“We’ve been seeking implementation of the report for four years but the Siddaramaiah government has not heeded our request under pressure from other Dalit communities,’’ says C N Muniyappa, a Dalit leader. In such a scenario, the JD(S), supported by BSP, could be looking to get Dalit backing in key seats. HD Deve Gowda, in an interview to TOI, was confident about the Mayawati-led party “winning some seats in Mysuru, Mandya and Bidar”.

But a former BSP leader said: “The real task for Dalits remains conquering the political space. There’s a strong perception that BJP and JD(S) have an understanding and BSP is only helping them by eating into traditional Dalit votes of Congress.”

As for BJP, it has some firefighting to do over last month’s Supreme Court verdict diluting the SC/ST Act and subsequent violence that left four Dalit activists dead in north India. “The SC/ST Act is sacrosanct for Dalits. There is a general feeling that Dalits’ rights, safeguarded by the Constitution, are under threat in Narendra Modi’s regime,’’ said Veeranjeneya, a Dalit Sangharsha Samithi activist.

Vokkaliga

2018: Some Vokkaligas angry with Congress, CM Siddaramaiah

From: Karnataka election 2018 :Why are Vokkaligas angry with Siddaramaiah?, April 11, 2018: The Times of India

HIGHLIGHTS

Vokkaliga passions are running uncharacteristically high against Siddaramaiah in the run up to the May 12 polls.

The epicentre of this Vokkaliga consolidation against Siddaramaiah is Chamundeshwari — his own assembly constituency in Mysuru district.

Not all Vokkaligas are against the Congress, and yet chief minister Siddaramaiah remains nervous. The reason: Vokkaliga passions are running uncharacteristically high against him in the run up to the May 12 polls.

The epicentre of this Vokkaliga consolidation against Siddaramaiah is Chamundeshwari — his own assembly constituency in Mysuru district. Not wanting to be pulled down by the Vokkaliga tide, Siddaramaiah is exploring other political options: One, consolidate the non-Vokkaliga votes in Chamundeshwari and two, contest from another safe seat in North Karnataka.

The big question though is why Vokkaligas (a dominant caste of South Karnataka which forms around 8% of the state’s population) are against Siddaramaiah?

“It is because Siddaramaiah’s words and deeds has jolted the community. Vokkaliga consolidation is a new phenomenon happening in this election,” said political analyst Muzaffar H Assadi. Although several factors are at play, one reason for the anti-Siddaramaiah sentiment is his call to end the political hegemony of former Prime Minister H D Deve Gowda. The JD(S) supremo is one of the most respected leaders of the community.

“The JD(S) has used Siddaramaiah’s political call to consolidate the Vokkaliga votebank,” Assadi said. “Anyone who is opposed to Deve Gowda and (his son) Kumaraswamy are dubbed adversaries of Vokkaligas. So Vokkaligas are coming together to teach Siddaramaiah a lesson.”

However, the hostility has been gradually building up ever since Siddaramaiah was made chief minister. Political dynamics in the rural setup changed after Siddaramaiah covertly began politically empowering members from his Kuruba community.

“Political disruptions were engineered to strip Vokkaliga leaders of power in cooperative societies and panchayat raj institutions,” BJP spokesperson A H Anand said.

Changes in the reservation matrix in the last five years ensured more Kuruba community members came onboard the managements of cooperative societies, agricultural produce marketing committees (APMCs), taluk and zilla panchayats, primary land development banks and district cooperative banks. “While Vokkaligas fought elections and won, the Siddaramaiah government paradropped Kuruba community members through official nominations,” said a revenue official in Mandya district.

Vokkaligas also feel they have been sidelined because of Siddaramaiah’s vindictive politics. “Be it IAS or KAS, not a single Vokkaliga officer was given a good executive posting in old Mysuru districts during Siddaramaiah’s tenure. On the other hand, members from the Kuruba community were promoted and placed in coveted posts in various levels of administration. Casteism worsened in the bureaucracy during Siddaramaiah’s regime,” a recently retired IAS officer said. “The CM’s body language towards Vokkaliga officers was always different, smacking of arrogance.”

Siddaramaiah’s stance with regard to reservation in promotions for government officials also angered Vokkaliga officials. “Siddaramaiah and his people made it clear that they wanted to control all instruments of power,” the retired officer said. “In fact, the promotion list of KAS officers (who would be given IAS) was kept on hold for more than a year as two officials from the Kuruba community had to be accommodated. On promotion, a Kuruba KAS community officer was made the deputy commissioner of Bengaluru Urban district. It was the same with IPS officers.”