Dowry: Pakistan

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Jahez

Bartering for happiness

By Sa’adia Reza

It is hard to tell when the concept of jahez became a commonality, but the most general belief is that the custom is the legacy of pre-partition days, and the giving of dowry has continued in Pakistan ever since its inception. Surprisingly, most people admit that taking dowry from the bride’s family is wrong but have let the practice flourish, mainly due to societal pressures on both the bride’s and the groom’s families, writes Sa’adia Reza

As the hot summer gears up for yet another wedding season, life for many families in Pakistan have turned into a frenzy of wedding-related activities. From endless discussions on innumerable joras with the tailors, to the everlasting trips to various jewellers, to choosing the right furniture, a wedding in our part of the world brings with it as much tension as it brings joy. Particularly for the bride’s family, there is an added burden in the form of dowry, or jahez, that has become an accepted, and expected norm of our society.

It is hard to tell when the concept of jahez became a commonality, but the most general belief is that the custom is the legacy of pre-partition days, and the giving of dowry has continued in Pakistan ever since its inception. Surprisingly, most people admit that taking dowry from the bride’s family is wrong but have let the practice flourish, mainly due to societal pressures on both the bride’s and the groom’s families.

So deep-rooted is the issue that nowadays it is almost unthinkable for a marriage to take place without a dowry being flaunted. So much so, that more often than not, mothers start collecting their daughters’ jahez since their childhood.

Perhaps this obsession for collecting dowry stems from the simmering insecurities in our society which spell out clearly that a sizeable jahez will automatically translate into worthwhile rishtaas. Unfortunately, this has led to a glaring disparity within classes, where girls from middle class and lower middle class remain unmarried because their parents cannot afford a dowry big enough to entice eligible bachelors. And it is often in these strata that the “demand” for dowry is most rampant.

“While the elite and upper middle class can afford such frivolities, they are setting up a wrong standard, which is making things difficult for the lower class,” says Arsalan. He is getting married this summer and has taken a firm stand against dowry. “When I first sent a proposal to my fiancée, I made it very clear that I was against such customs, and have told her to bring a few things that she requires if she wants to.”

Fortunately Arsalan’s family is supportive, and has not raised any hue and cry on his decision. Farheen was not so lucky. Taking a bold step, the bride and the groom had decided that she would not be bringing anything with her in the form of dowry. “But this decision has worked against me,” says Farheen, who continues to be taunted by her in-laws for this step.

This is another reason why most parents are scared of not giving their daughters dowry. In this day, it seems that the marital happiness of a woman is directly proportional to the number of dowry articles she brings with her.

Then, of course, there are also cases when the groom’s family would send a list of their demands days before the wedding, knowing very well that the bride’s family would be forced to cater to it. Farheen gives the example of her cousin, whose would-be in- laws sent a list a week before the wedding ceremony, leaving the poor parents with no choice but to give in to the demands. Lack of awareness coupled with the desperate attempt to avoid a scandal, and to get their daughters married off, makes many such parents succumb to the in-laws’ greed and unreasonable demands.

Not that their fears are unfounded. Lawyers agree that most cases of domestic violence, particularly from the lower stratum, are dowry-related, even though they are reported as domestic issues. Since generally the groom’s family is not very resourceful, it looks upon the sons’ wives to bring the different amenities and luxuries with them.

Often when the demands are not met, wives are harassed by every possible means. Stove burning is one of the common incidents that happen to women who disappoint their in-laws in terms of jahez. Even more common is the continuous mental and physical torture that is inflicted upon the poor daughter-in-law and her family.

Since the cases are not reported as dowry-related, the issue has not been given the focus that it deserves in Pakistan. Unlike India, where many NGOs are actively working against this evil, the Pakistani society has yet to pay enough attention to make a difference. More often, it is the women themselves who camouflage the reason behind their sufferings in order to save their marriage. Unfortunately, our society festers a deep-rooted insecurity for single or divorced women, particularly in the lower class. Hence, no matter what sufferings they undergo, women prefer to cling to their marital bond.

“Ironically, in spite of very high frequency of domestic violence and frequent cases of stove deaths, dowry-related violence is neither perceived nor recognised as an accepted form of violence nor documented in social science literature,” says Dr Rakhshanda Perveen. Dr Perveen is a gender activist and the Executive Vice President of SACHET (Society for the Advancement of Community, Health, Education and Training) which recently launched Fight Against Dowry (FAD), a campaign attempted to sensitise the masses with the repercussions of this evil.

Dr Perveen feels there are three main reasons for the lack of focus on dowry related issues. Firstly, it is the spiral of silence and the sharam, which implies that women-related issues must not be taken out of the premises of home for the sake of honour. Secondly, the ironical fact that attention to the role of dowry in our marriage system has not gained the attention of international donors. As the hype stirred by comparable social problems like child labour or environment overshadows a traditional area like dowry and related issues. Thirdly, the Ministry of Women Development in Pakistan has yet to acknowledge dowry and dowry-violence as gender issues.

Dr Perveen also adds that a few localised and limited efforts by small-scale welfare societies in the 1960s and 1970s aiming at awareness raising and motivation campaigns to convince people at the mohalla level, did take place. However, with the advent of international donors in the 1980s, NGOs in Pakistan have either undertaken campaigns against other more visibly anti-women oppressive mechanisms like Hudood Ordinances or political marginalisation under the Zia regime. The NGOs have taken up issues of expressed violence being symptomatic and not delving into the deep rooted causes of violence against women, dowry being one primary cause.

According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), the extreme form that domestic violence took included driving a woman to suicide or engineering an accident through the infamous ‘stove burning’. This happens usually when the husband, often in collaboration with his side of the family, feels that the dowry or other gifts he had expected from his in-laws were not forthcoming or/and he wanted to marry again or he expected an inheritance from the death of his wife. Unfortunately, in these cases, the police follow-up is also negligible, and resultantly, no effective stand is taken against the issue.

Another important reason why the concept of dowry has comfortably seeped into our culture is that people tend to relate it to Islam. Many people, both from the bride’s and the groom’s family, argue that even the Prophet (P.B.U.H) gave his daughter some modest articles in the form of dowry. “People translate those articles in accordance with today’s times,” says Amber who got married recently. “The charpai becomes bedroom furniture, the matka becomes the refrigerator and so on.”

However, not many people are aware that the articles that Hazrat Fatima brought with her at the time of her wedding, were bought by Hazrat Ali, and were actually her mehr.

According to Sheikh Syed Darsh, Chairman of UK Shari’ah Council who is an expert on family matters, the question of dowry is one of the rights of Muslim women as part of their correct contract of marriage. “It is not Islamic to ask the woman to give dowry to the husband,” he says while answering a query regarding the issue, on a website. “This is not a noble thing to ask a woman. The Islamic requirement is not because the man is going to buy the woman, it is to express his love, care and the dignity of the woman. Whatever expresses these sentiments, great or small, is considered to be acceptable, simply because it expresses these feelings.”

This means that a bride or her family is not obliged to give anything to the groom’s family at the time of marriage. Unfortunately, cultural influences have ingrained this concept and apparently removed negative connotations from it. Even in families where the in-laws do not demand anything, the bride’s family goes out of the way to prepare an extravagant dowry, often beyond their means. And much as they like to argue that they are doing it out of their own free will, they cannot escape the fact that dowry is an extra expense to the already phenomenal budget.

“The reason why I’ve taken a conscious decision against dowry is because I’ve been through the tension when my elder sister got married,” says Arsalan. “Although her in-laws are very decent people and did not demand any jahez, our family was under pressure to come up to a certain standard that the society has set. Which is why I believe that it should be the men in our society who need to take a firm stand. The bride’s family will always be under pressure.”

Sumaira, Arsalan’s fiancée, is equally against the custom but feels that it is not possible for the girl to get married in just “two joras” as the phrase goes. “I think a few articles are necessary for the girl’s own comfort,” she explains. “Being a working woman, I would rather take a wardrobe with me that I feel most comfortable in.”

Sumaira also believes such sensitive matters need to be worked out well before the wedding day. Often, people hesitate to discuss these matters because they feel it might offend the other party. However, it is best to iron out all confusions in order to reduce the tension.

Asma, who got married a year-and-a-half ago, concurs with this viewpoint. “Since my husband and I belong to two different cultures, our mothers sat down well before the wedding to discuss all the traditions and customs.” Asma and her husband moved into a separate house after their wedding, and both the parties furnished the house chipping in equally.

“My mother-in-law told my parents categorically that I was only to bring strictly what I would be using and nothing more. She also clarified that whatever I will be bringing will be for my use only, and has so far never asked me what I did with my dowry.”

But since Asma belongs to an elite set up, she did not face any financial problems, even if the families did contribute equally. But there are many who maintain that it is the bride’s family that has to bear the brunt. “Why should the bride’s family give anything to set up the house?” asks Arsalan. “Jis ke ghar jaa rahi hai wo bhi to kuch khareeday.” Sumaira also agrees that both the husband and the wife should finance their venture, if the wife is working, instead of relying on the families for financial support.

Then there are brides who have actually looked forward to getting married so that they could procure a decent dowry which they can call their own. Says Mrs Anis, a mother of two young men, “When I got married around thirty years ago, my husband lived alone, and we did not have much to set up our apartment with. And so my family provided all the furnishings besides the traditional trousseau and jewellery. So in a sense, I’m in favour of jahez, since it helped me begin a new life.”

Mrs Anis also points out that in some families women are bereft of their inheritance, and so the parents strive to give their daughters as much as possible at the time of marriage. But Dr Perveen counters this argument when she says that often dowry is used as an excuse for denial of inheritance to women. The expenses on dowry and wedding are unilaterally decided by the menfolk of the family as transfer of inheritance by other means.

The lack of attention on the issue resulting in its social acceptance, has led to major serious marital upheavals in the society. In problems like these, it is the social awareness that make a better impact than any law. If the girl herself takes a stand against dowry and is supported by her family, the chances are that the custom will come under limelight, as it has happened in India, where brides themselves are calling off weddings if the groom’s family makes any unreasonable demand. Also, if the men of the society begin to say no to dowry and demand that the family respects their wish, the evil will hopefully be eradicated from society eventually.

Illegally yours

Despite the fact that practice of giving dowry is rampant in our society, there are hardly any laws to counter it. And the only law that does exist is inconsequential since either people are completely unaware of it, or choose to ignore it. The Dowry and Bridal Gifts (Restriction) Act, 1976, says that the maximum amount of money that can be spent on preparing a dowry should not exceed Rs5,000. It also adds that the bridal gifts cannot be of more than Rs100. The law states that the wedding expenditure should not exceed Rs2,500. So far, the act has been amended only once, and that too on the provincial level, to increase the amount. However, the exact amount set after the amendment could not be ascertained.

Unfortunately, the law is restrictive rather than prohibitive, which means that the dowry’s worth may not exceed the stipulated amount, but if it does, it would not be illegal. As a rule, a list of all the dowry articles and the bridal gifts are to be submitted with the court, but obviously that never happens either.

“Unless and until a complaint is filed against the concerned parties, excessive dowry will not be termed as a legal offence,” says Barrister Zoha Shafi. “The complaint has to be made in writing under or by the deputy commissioner within three months from the date of nikah. And if the rukhsati takes place some time after nikah, then from the date of such rukhsati,” she explains.

Even though the law was formed to protect women’s right, in actuality it is detrimental to them. Husbands have used this law to deprive the wives of their property. This happens when a marriage is consummated, and husbands use this law to bereave their wives of the dowry exceeding the Rs5,000 mark. Shafi cites an example from the late `80s where a woman filed lawsuit against her husband for the recovery of Rs15,000 as the price of her dowry articles lying in his house. The husband had pleaded that at the time of leaving the house, the wife had taken property worth 10,000 rupees. However, the judge ruled that since the maximum dowry allowed by court should not exceed Rs5,000, the wife’s claim was curtailed to as much only.

Given the dormant nature and the loopholes in the law, it is no surprise that the practice of excessive dowry has dug its roots deep in the society. Also, there is no Islamic sanction behind the act, and in effect it goes against the Quranic injunctions, which says that a woman has a right to her dowry and bridal gifts in the event of dissolution of her marriage. Perhaps this is why the framers of this law chose to keep it restrictive and not prohibitive. — S. Reza

A bride-to-be’s view

By Samina Wahid Perozani

Sometime back, when I got engaged I made a few “pre-wedding” resolutions. From vowing to look like the next Victoria’s Secret model (just in time for the wedding, of course) to sticking to the time-tested ‘my way or the highway’ philosophy, I had a whole mess of theories about how exactly I wanted my wedding to be. Less is more, they say, and that is exactly what I was intent on pursuing –– with a vengeance.

But that was then. Now as D-Day draws perilously close, I am honestly beginning to believe that the universe has conspired against me. Of course, in my case, the universe we are talking about is the meddlesome, cumbersome society that we are accustomed to putting up with in a subservient, apathetic fashion. It began with the little things –– things like scented candles, elaborate bedspreads and yards of silks and chiffons for my trousseau. “But why?” I would often ask my mother only to be told that it was a custom that she felt compelled to follow right down to the T.

Don’t get me wrong, my in-laws have never pushed my parents into doing the needful –– giving their daughter every conceivable thing that she could possibly need during the course of her marriage –– unlike tales about jahez-hungry, greedy parents of the groom that one gets to hear every now and then. In spite of that, they feel like they owe it to me and to the world in general to give things to their daughter.

Added to this is the fact that I belong to a family in which the sky’s the limit when it comes to a girl’s trousseau. There have been stories about the prospective bride and her folks flying off to places like Dubai, Singapore and Bangkok to indulge in many a shopping spree. Furniture from up-scale home stores, platinum and diamonds, silverware and Teflon-coated pots and pans are some of the extravagances that the bride’s family takes great pride in.

So not surprisingly, at some level, the pressure to give one’s daughter a decent trousseau is always lurking. What’s worse is the brazen display of these items during one of the kick-off wedding functions for the benefit of all-too-curious aunties and their progeny. Probing questions like the amount of gold that went into a particular jewellery set, who gave what to so and so, whether the bridal bed spread was made to order or one of those god-awful, mass produced things, and the colour of the lingerie are considered to be commonplace, nay, a birthright that must be exercised at all costs, at weddings in my family.

So parents have to go to great lengths to buy extravagant items for their daughter to keep the gossip at bay. But people being people talk anyway and all that effort goes right down the drain. It turns out that no matter what one does, chances are that malicious gossip will go around for months after the wedding.

No matter what the circumstances, marriage is a stressful time for both the boy and girl and their respective families, given the emotional baggage that comes with the process of tying the knot. Making unreasonable demands from the bride’s family only makes matters worse, who in most cases feel that they do not have a choice and must live up to the expectations of the society.

In all of this, one often forgets that marriage is about two people who are willing to go the distance and spend the rest of their lives with each other –– a Herculean task to say the least. It is hardly up to the Armani suits, Persian carpets and Japanese DVD players to make the marriage work, so why bother splurging on such things when it is clearly the responsibility of the bride and the groom to value their commitment to each other?

For this reason, it is probably a good idea for both of them to put their foot down when it comes to dowry. Talking to their families about the futility of dowry could set the ball rolling in the right direction. If that doesn’t work then both sides could make an equal monetary contribution to the newly-wed couple to help them out, if financial assistance is at all needed. That would significantly reduce the burden that the girl’s family is forced to bear. Also, they won’t have to bother about wagging tongues, because let’s face it, we are prone to losing sleep over what people think.

Easier said than done, right? Here’s what I think should really happen: the girl’s parents should be given lavish gifts because after all, they are sending off their daughter to uncharted territory (depending on whether the marriage is arranged or not) where she may or may not be treated well.

It makes perfect sense if you think about it for since marriage is tantamount to winning the lottery for the groom and his family and the stakes in most cases are rather high for the girl, the latter’s parents should at the very least receive some sort of compensation for their irreplaceable loss.

Dowry

Dowry — alive and kicking

By Shehar Bano Khan

We call ourselves Muslim because we pray five times a day, give zakat, perform Haj, fast during Ramazan and believe there is one God and Muhammad (PBUH) is His Messenger. But the relationship between Allah and a human is more than the performance of rituals. It lies in how the religious code is undertaken to touch people’s lives. By those standards only a few can truly call themselves Muslims!

Whether it is inheritance, remarriage or dowry, we try to skirt around the religious code to make it fit our demands. Families try to deprive women of their rightful inheritance; widowhood or divorces are frowned upon, and in extreme cases considered dissolute if the will to remarry is shown. One of the most blatant defiance of the Islamic religious code is at full play when marriage meets flamboyance in the form of dowry and display.

Austerity preached by religion is forgotten. Consideration to avoid extremity is overtaken by the need to sustain customs and traditions antithetical to Islam. Dowry is one of those customs which has no precedence in our religion, and yet forms an elemental part of our society. Right from the most affluent down to the most financially deprived, the custom of dowry is a direct violation of the essence of this dynamic religion called, Islam. But nobody has the desire or the will to dismantle it.

The concept of dowry does not exist in Islam. On the contrary it enjoins the groom to give a ‘bridal-gift’ or ‘dower’ as a token of love and assurance to his wife at the time of marriage without which marriage cannot be solemnised. An Islamic wedding following the religious code is a simple nikah ceremony performed by a qazi and witnessed by close relatives and friends. There is no compulsion on the bride’s family to host lavish banquets, as is mostly the case. In fact, the groom is required to give a reception (valima) after the nikah.

Those precedents set by the Prophet (PBUH) to suit women are wilfully forgotten. Marriage nowadays is a series of extravagant events, according to the social placement of families, taking expenditure to a level of vulgarity. A bride’s parents end up overstretching their means, if they are limited, for the sake of tradition they dare not go against. Dowry has become a statement on the stature of parents and in all its moral morbidity a token of validation of their daughters’ worth.

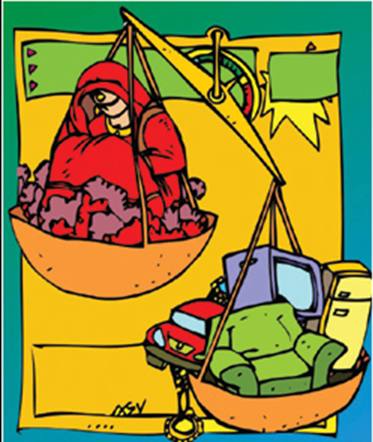

The existence of dowries in developing countries like Pakistan as pre-empted bequest to daughters undermines the concept of gender equality, making them appear as inferior partners in marriage unless supported by material accompaniments.

Contrary to religion, women in our society usually have no ownership rights to inheritance or property making them economically vulnerable. A dowry intended primarily to endow daughters with some financial security in a marriage has had a reverse effect on their positions. Instead of giving them security the institution of dowry as transfers from parents to daughters has helped to maim their independence. Their economic dependence from the time of birth to marriage puts them in a weak position giving perpetuity to the ‘burden’ legacy.

It is difficult to put a date to the establishment of dowry. Some sociologists document it to the ancient Greco-Roman time. During the Middle Ages dowry as bride-price prevailed through much of Europe and continued to exist in the Renaissance period. Then came the era of enlightenment, progress and development and brought in its wake the awareness among women not to be bartered as commodities.

Even though brides in South Asia are not bartered literally, their bride-price as dowry has little to show by way of nuptial development. According to a study, Dowry and Property Rights done by Siwan Anderson, professor of economics at the University of British Columbia, in 2004, approximately 4,700 households were surveyed in Pakistan to collect data on dowry.

Information on dowries was collected from females who had married in the past five years. “Nearly 800 responded to the dowry question and of those, roughly 700 received a dowry from their parents and reported the value and contents of the transfer. A very large proportion of the sample, 87 per cent, paid a dowry (88 per cent in urban areas and 86 per cent in rural areas).”

Not only is the payment of dowry a contradiction to Islamic values, it is a breach of the 1976 Dowry and Bridal Gift Restriction Act. The Act fixed the upper limit of Rs5,000 for dowry and Rs2,000 as maximum expenditure on meals at a marriage ceremony. Of course, nobody adhered to the legally prescribed upper limit in Pakistan and dowry continued as an essential part in every social stratum. But interestingly enough the same upper limit of Rs5,000 was used by the groom’s side at the time of divorce suits filed to recover dowry. Since the upper limit could not exceed Rs5,000, the groom’s side was not legally bound to pay the rest. There have been many instances of women being deprived of their dowry after divorce as a consequence of legal misinterpretation.

In 1993, the Pakistan Law Commission recommended amending and updating the 1976 Act and suggested the limit for dowry to be increased to Rs50,000 in the case of urban areas and Rs20,000 in rural areas. The wedding expenditure was raised to Rs25,000 in the urban and Rs10,000 in the rural areas. The law continued to be flouted and in 2003 the Law Commission again announced that it was preparing a draft law on Marriage and Expenses, Dowry and Bridal Gift (Restriction) Act 2003 to replace the 1976 Act.

But laws have never made this society compliant for the simple reason that accountability in case of non-compliance has become a non-compulsion. Twenty-four-year-old Zubeida does not know of any dowry restricting laws. Since she got married two years back her life has been an account of misery and torture given to her by her husband and in-laws for failing to bring adequate dowry. She refuses to admit the left side of her charred face is caused by a deliberate attempt on her life by her in-laws. “No, it was my fault. I did not check the stove before lighting it. It’s been two months now that it burst and burnt me. My husband came to my rescue and doused the fire. I was taken to the Mayo Hospital where I stayed for a month and underwent two operations,” narrates Zubeida. But her elder sister, Gulshan, has an altogether different perspective on it.

She accuses Zubeida’s in-laws of trying to kill her so that her husband can remarry a financially stronger woman. “My father had promised Zubeida’s in-laws a dowry worth Rs500,000. At the time of marriage he could only arrange Rs200,000. He begged my sister’s in-laws to look after Zubeida and told them that within three months he would pay the remaining amount in cash,” says Gulshan.

Zubeida’s father, Hameed gave the remaining amount, not realising the in-laws’ demands would not end with payment. “Sometimes they want a new TV, at other times Farooq, Zubeida’s husband asked her to get money for a new motorbike. My father owns a small shop in Dharampura and has a huge family to support. We couldn’t afford their demands,” reveals Gulshan.

A few weeks into marriage gave Zubeida her first encounter with domestic violence. For an entire year her husband’s beating bouts were kept secret from her family till Gulshan came to visit her. “Her upper lip was cut and swollen. She had bruises on her forehead and walked with a limp. I wasn’t stupid and knew something was wrong. Zooby made me promise not to tell the family that Farooq was beating her for not getting him a motorbike from the father. He also doesn’t want her to have any children and is always threatening to divorce her. I’ve told her to leave him but she wouldn’t listen. She says that all the money abba gave as dowry would be wasted if she was divorced. I’m sure they tried to burn her alive. Zooby would rather die than come back to us,” says her tearful sister.