The Languages of India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Additional information may please be sent as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Classical language status

What is a classical language?

Bhavika Jain, Oct 7, 2024: The Times of India

The Union Cabinet on Thursday expanded the list of India’s ‘Classical Languages’ to 11 by including Marathi, Pali, Prakrit, Assamese and Bengali in it. Tamil, Sanskrit, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam and Odia were already members of this league. Tamil was the first to get ‘classical’ status in 2004, while Odia, the sixth, got it in 2014.

“Classical Languages serve as a custodian of Bharat’s profound and ancient cultural heritage, embodying the essence of each community’s historical and cultural milestones,” Union minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said.

How Is A Language Selected For ‘Classical’ Status?

The category of ‘Classical Languages’ was created on Oct 12, 2004, with Tamil being the only entry. In November that year, the ministry of culture created a Linguistic Experts Committee (LEC) under the Sahitya Akademi to examine the eligibility of other possible contenders. Sanskrit was declared a ‘Classical Language’ in 2005, Telugu and Kannada in 2008, and Malayalam and Odia in 2013 and 2014, respectively.

A govt press release says selection criteria for a ‘Classical Language’ have been revised twice since 2004, the last time in July this year. These are:

➤ High antiquity of (its) early texts/recorded history over a period of 1,500-2,000 years. A body of ancient literature/texts which is considered a heritage by generations of speakers.

➤ Knowledge texts, especially prose texts in addition to poetry, epigraphical and inscriptional evidence.

➤ The ‘Classical Language’ and literature could be distinct from its current form or could be discontinuous with later forms of its offshoots.

➤ The older criterion that a language’s “literary tradition be original and not borrowed from another speech community” has been dropped.

What Changes For Language After Gaining ‘Classical’ Status?

The govt promotes the study and preservation of ‘Classical Languages’.

➤ Two major annual international awards for scholars of eminence in classical Indian languages.

➤ A Centre of Excellence for Studies in ‘Classical Languages’ has been established to support advanced research.

➤ University Grants Commission (UGC) is requested to create professional Chairs in central universities to support the study of ‘Classical Languages’.

For example, in 2020, three central universities — Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan, New Delhi; Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha, Tirupati; and Sri Lal Bahadur Shastri Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeeth, New Delhi — were established to promote Sanskrit. Likewise, the Central Institute of Classical Tamil was set up to facilitate the translation of ancient Tamil texts, promote research and offer courses for university students and language scholars of Tamil. Centres of excellence for studies in classical Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam, and Odia were established under the Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysuru.

States with ‘Classical Languages’, such as Odisha and Tamil Nadu, are entitled to annual grants for the study, research and promotion of their languages.

How Marathi, Bengali, Assamese Got This Status

In July 2013, a committee headed by Prof Rangnath Pathare submitted a report to the Centre. Professor Hari Narke, coordinator of the 10-member committee that gathered evidence to show that Marathi is at least 2,300 years old, said, “It is a wrong perception that Marathi is an offshoot of Sanskrit or that it is merely 800-1,000 years old.” Narke said the committee submitted 80 pieces of documentary evidence to show that Marathi is an original language.

In 2023, the state higher education department of the West Bengal govt established the Institute of Language Studies and Research (ILSR) to advance knowledge in language studies, translation and cultural research. The institute gathered evidence for two years and prepared a draft that was submitted to the Centre. West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee wrote to PM Modi in 2024, urging the acceptance of Bengali as a classical language.

Assam CM Himanta Biswa Sarma on October 1 said his govt is in “regular contact” with Modi and the Centre to recognise Assamese as a ‘Classical Language’. On his X handle, Sarma stressed why it should be granted ‘Classical Language’ status.

Is Conferring This Status Also A Political Tool?

Conferring ‘classical’ status on a language has political implications, particularly during the election season. Recognising the cultural heritage of a specific linguistic group allows parties to garner support in regions where language defines identity.

Language has long been a significant tool in identity politics. For example, the UPA-led Centre accorded ‘Classical Language’ status to Tamil after the DMK-led alliance swept the 2004 state elections. DMK patriarch M Karunanidhi offered support to Manmohan Singh’s UPA govt on condition that Tamil be granted the status of a ‘Classical Language’. Five of the first six ‘Classical Languages’ — barring Sanskrit — were spoken in South India. This time, the states whose languages have been chosen form a belt from west to east: Maharashtra (Marathi), Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (Pali and Prakrit), West Bengal (Bengali), and Assam (Assamese).

Was Marathi Included With Eye On Maharashtra Polls?

The first proposal to include Marathi in the list came from a Congress-led Maharashtra govt in 2013. The decision has come a decade later when BJP and its allies run both the Centre and the state. It’s also timed very close to the state elections. Political observers say this decision can be used to seek votes in the name of Marathi asmita (Marathi pride).

Do Such Titles Create Language Hierarchies?

Rating languages can give rise to the perception that some languages are more prestigious or culturally significant than others, especially in a multilingual country like India. The Marathi versus non-Marathi political narrative in Maharashtra that has fuelled several elections is a classic case of language hierarchy in the state. Sentiments against Hindi and Gujarati are reinforced during the elections. Even down south, leaders of political parties in Tamil Nadu, including the late M Karunanidhi, criticised the Union govt’s attempts to promote Sanskrit in schools by mandating the three-language formula.

Languages spoken in India

As in 2011

February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 21, 2020: The Times of India

See graphics:

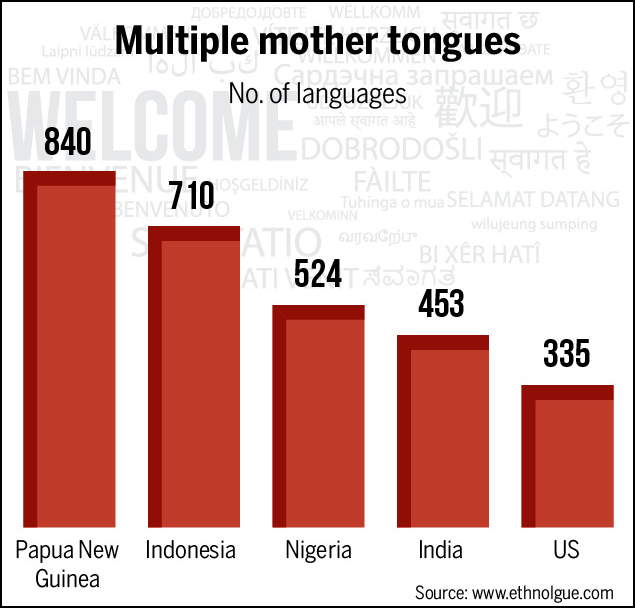

People with multiple mother tongues in India, the USA and other countries.

Endangered languages in India, presumably as in 2011

The presumed first language of the various states of India, as in 2011. This map makes easy generalisations and assumes that all of, say, Jammu & Kashmir (including Ladakh) speaks the same language, and that language is Kashmiri.

The presumed second languages of the various states of India, as in 2011. This map, too, makes easy generalisations. It does not show Lakshadweep where Hindi is widely studied.

The third language of the various states of India, as in 2011. This map makes easy generalisations

The languages that Indians speak, presumably as in 2011

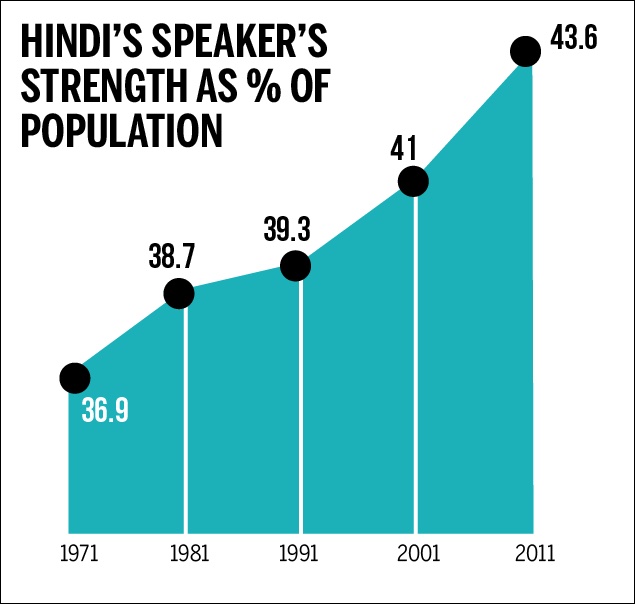

Hindi's speaker's strength as % of population, 1971- 2011

Distribution of people counted as Hindi speakers; Source- Census 2011

UNESCO, which designated February 21 as International Mother Language Day, says that every two weeks, a language disappears in the world. India, which was once home to the second largest number of languages spoken in a country, has seen several of its languages disappear.

Languishing languages

From 780 languages spoken actively, India today has fewer than 500 languages spoken. According to the People's Linguistic Survey of India conducted a decade back — in 2010 — 600 of these 780 languages are endangered. That means children do not learn these languages or their only speakers happen to be grandparents. Just how critical is the situation in India may be gauged from the survey's findings that of the 4,000 endangered languages globally, India’s share is 10%. Since Independence, India has already lost 250 languages.

North East is home to several endangered languages

According to the HRD ministry, in a reply given to the Parliament in 2014, based on data from UNESCO, 42 Indian languages are “critically endangered” — which means that "the youngest speakers are grandparents and older, and they speak the language partially and infrequently". However, there are several times that number which face the threat of extinction — called "definitely endangered", meaning that "children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home" and "vulnerable", which implies that while "most children speak the language, but it may be restricted to certain domains (such as home)". The worst affected is India's North East — with Arunachal Pradesh alone home to 29 endangered or vulnerable languages.

Counting them out

Part of the reason why India's languages 'die' is also due to the fact that after the 1971 Census, any language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people was not included in the list of official languages — which also include the 22 official languages under the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages). That, incidentally, is the highest number of official languages for any country. With the next Census due in 2021, it remains to be seen if any other languages went extinct in India — between the 2001 and 2011 Census, the number of official languages in India declined from 122 to 121.

India is truly multilingual

Although several of India's languages are under threat, the country continues to have rich linguistic diversity. Most Indians speak more than one Indian language from the 22 official languages under the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution . The three language maps below show the real mix of languages across the country. According to the 2011 Census data of scheduled languages (prior to Andhra Pradesh's division), more states and union territories speak Hindi as the second language (14) than first (12).

After Hindi, Punjabi is the most popular second language in most number of states or UTs (5), followed by Urdu (4). Urdu is the most popular third language (8). Nepali is the second language in one state (Manipur) and third language in five (Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Mizoram and Meghalaya).

However, it is Hindi that is spoken most widely

While several languages are spoken in the country, it is Hindi that is spoken by the majority. About 57% of Indians speak Hindi, although it has many dialects. Worldwide, English remains the most-spoken language. Even in India, it is the second-most spoken language — and it cuts across linguistic groups.

Among 22 scheduled Indian languages, Hindi grew fastest In fact, while other languages may be declining, Hindi speakers are growing. In 1971, people identifying Hindi (including dialects) as their mother tongue were 36.9% of India’s total population. This increased by 6.6 percentage points to 43.6% in 2011 — the highest for all scheduled Indian languages. That is about 52 crore of the total of 121 crore Indians. The growth in Hindi can largely be attributed to the higher fertility rate in the Hindi belt.

The many strands of Hindi Official Hindi, which is based on Khariboli dialect was developed in the late 19th century. Many of the dialects that are included in it predate the language, including Rajasthani and Braj, as well as the works of Tulsidas, Kabir and Amir Khusrow.

61% of all native Hindi speakers say they speak official Hindi. Overall this constitutes just over a quarter of India's population (26.6%). Hindi has about 60 regional dialects.

Language for all- India examinations

Test can’t be in just Hindi, English: HC

K Kaushik, Oct 26, 2021: The Times of India

The Madras high court has suspended an aptitude test for a centrally-sponsored scholarship programme — Kishore Vaigyanik Protsahan Yojana (KVPY) — slated for November 7 as the examination was to be held only in English and Hindi.

The first bench of Chief Justice Sanjib Banerjee and Justice M Duraiswamy ordered the postponement of the test while hearing a plea that sought the exam in all regional languages. The court also sought response from the Centre on the steps taken to conduct the exam in multiple Indian languages.

Rejecting the Centre’s submission that it does not have adequate personnel to assess answers given in various languages and that it may be difficult to find an equivalent term in local languages for scientific words and terminologies, the judges said, “It would not do for the Centre to say that it does not have qualified assessors to appreciate the material put up by non-Hindi- and non-English-speaking aspirants. If at all, it is the deficiency with the Centre, and young aspirants from non-Hindi- and non-English-speaking belts in the country should not suffer on such grounds.”

KVPY is a national programme of fellowship in basic sciences funded by the Centre’s department of science and technology. The main objective of the exam is to identify students with talent and aptitude for research, to help them realise their academic potential and to encourage them to take up research careers in science by providing fellowships. Even if it is a token scholarship of Rs 5,000, it amounts to recognition of a young mind, said the court.

The local language and students from outside the state

The local language cannot be imposed on outside students

Oct 27, 2021: The Times of India

Can’t force outside students to learn Kannada, says HC

BENGALURU: Students coming from outside Karnataka cannot be compelled to learn Kannada language, be it classical or functional, the high court orally observed, granting time to the state government to reconsider the issue.

A division bench headed by Chief Justice Ritu Raj Awasthi adjourned the hearing to November 10 vis-a-vis a petition challenging two government orders making Kannada a compulsory subject for degree students, following a request from advocate-general Prabhuling K Navadgi.

“With the understanding that the government will reconsider the issue, we adjourn the matter,” the division bench orally said. Earlier, the advocate general said people have to learn Kannada for employment purpose and they need not learn Kannada in a classical sense and he would get more instructions in the matter. However, the bench queried as to how the state government can compel a student coming from outside to learn Kannada and added that the state government has to reconsider the issue and the court will grant time for the same. Senior advocate SS Naganand, appearing on behalf of the petitioners, told the court that the academic year had already commenced and students will have to make a choice.

Orders take away freedom to choose language: Petitioners

Samskrita taka) Trust Bharati , Bengaluru (Karna , - and three other institutions associated with the promotion of Sanskrit language/ study have filed this petition, challenging the validity of government orders dated August 7, 2021 and September 15, 2021, saying it goes against National Education Policy.

The petitioners have sought declaration to the effect that NEP 2020 does not impose any restriction upon the student to choose any particular language as part of the curricula for higher education. According to the petitioners, it will impede the admissions and rights of minority institutions, students and especially the teachers who are at the risk of losing employment as the options of choosing a language is now restricted.

They claim 1.3 lakh students and 4,000 teachers, who were teaching Sanskrit (600 teachers), Hindi (3,000 teachers), Urdu (300 teachers) and other languages (100 teachers), are going to be affected by this move of the government.

“The said orders take away the freedom to choose a language for study and makes it mandatory for all students in Karnataka to take up Kannada as a language in degree courses offered in all streams of science, commerce and arts. There is a restriction on the freedom of speech and expression enshrined under the Constitution. Though, Article 19(2) of the Constitution enables the state to impose restrictions upon the fundamental rights, the restrictions ought to be reasonable..,” the petitioners contended.

Further, they have argued that equating those students who have not studied Kannada at any point time till plus level with those who have studied Kannada is also equally opposed to Article 14 of the Constitution.