Motherhood: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Adolescent fertility

2015, 2021

Sushmita Choudhury, May 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury, May 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury, May 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury, May 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: Sushmita Choudhury, May 14, 2022: The Times of India

Four in 10 Indian adolescent girls aged 15-19 years, who have had a live birth or who are pregnant with their first child, are just 16 years old or under. Nearly 60% of the country's teenaged mothers are under the legal marriage age.

Yet, as per the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), there are no premarital teenaged pregnancies in India.

That means that the eradication of child marriages — something India has promised to do as part of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development — is still a distant dream. In the survey, over 13% of the adolescent girls in the country declared themselves as married.

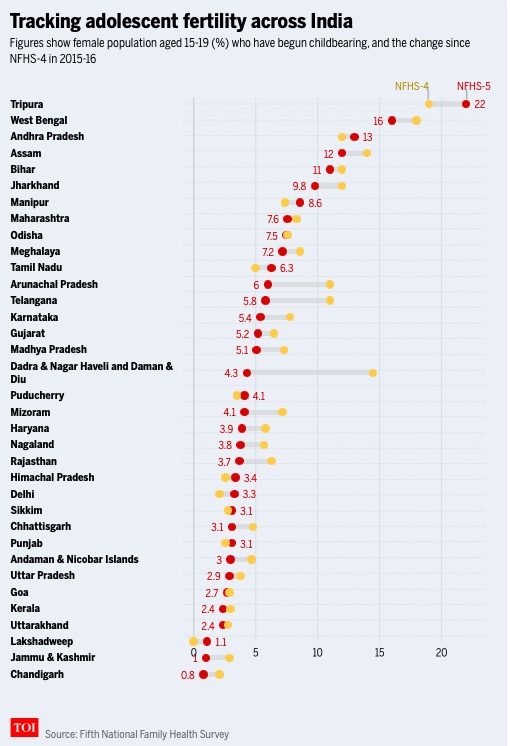

The recently published data carries plenty more surprises. Like the fact that although the level of teenage motherhood in the country declined slightly from 8% in 2015-16 — NFHS-4 survey — to 6.8% in 2019-21, 10 states and Union Territories including Delhi, Punjab and Tamil Nadu have posted an uptick.

In Tripura, the number of minors who are mothers increased by three percentage points to 22%, or three times the national average, in the latest survey. For context, in Rajasthan, a state long infamous for child marriages, the corresponding figures have reduced from 6.3% to 3.7%.

More than half (53%) of currently married adolescent girls have already begun childbearing. That’s a slight rise of two percentage points since the previous survey. Although over 95% of this demographic segment claim to know at least one modern method of contraception, including condoms, pills and sterilisation, their actual usage among the married girls of this age group is under 19%.

The good news is that the proportion of women who have started childbearing rises sharply from 2% at the age of 17 to 6% at 18 years and 17% at 19 years.

The best and worst performers

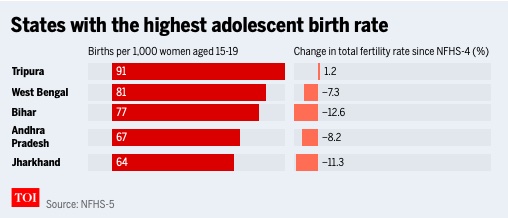

Age-specific fertility rates in the five-year period before the survey show that fertility has declined in all age cohorts from NFHS-3 to NFHS-5. The average adolescent fertility rate, or births per 1,000 women in the 15-19 age group, has dived down from 90 to 43. But on a state-level, the survey throws up massive differences.

The states with the highest adolescent fertility rate are Tripura, West Bengal, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh and Jharkhand. Tripura is also the only northeastern state — and one of just four states and UTs across India — to post a marginal rise in the total fertility rate since NFHS-4.

When even one child born to girls under 14 is one too many, Tripura posted 3 births per 1,000 girls in the 10-14 age bracket for the 3-year period preceding the survey. The only other states reporting age-specific fertility rates for this age bracket are West Bengal and Arunachal Pradesh (1 each).

The states with the lowest percentage of teenaged mothers are Uttarakhand, Kerala, Goa, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab.

The correlation with education levels

Across the country, although only 4.4% of female adolescents have no schooling — against close to half of women aged 45-49 years — this group bears the lion’s share of teenaged pregnancies. The proportion of childbearing adolescents is much higher among those who never went to school (17.7%) compared to those with 12 or more years of schooling (4.2%). In the case of Tripura, for example, a vast majority — close to 40% — of women in the 15-49 age bracket have completed only nine years of schooling, or less.

The other factors at play

Teenage pregnancy is relatively high in rural areas, no surprises there. Nearly 8% of girls in this age group in rural areas have begun childbearing — down from 9.2% in NFHS-4 — compared to 3.8% of urban adolescents. In the previous survey, the urban figure stood at 5%.

Adolescent birth rates are also inversely related to the level of a household’s wealth: 10% of teenagers in the lowest wealth quintile in the survey have begun childbearing against 2% in the wealthiest households.

The survey reveals that teenage childbearing is higher among scheduled tribe women (nearly 9%) compared to among scheduled castes and other backward classes. But this rule does not apply evenly across the states and UTs. For instance, in Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur and Jharkhand, where the scheduled tribes account for at least a quarter of the state population, adolescent birth rates are very high.

Yet, there are shining examples like Nagaland and Chhattisgarh that have made huge strides in curbing this problem despite being poor states with tribal communities accounting for 30-87% of the population.

The impact on maternal and child health

Teenage pregnancies not only rob the girl child of her childhood but also spell adverse economic impacts for the rest of her life. It is also associated with a significantly increased risk to maternal and child health. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading killer of 15- to 19-year-old girls globally and it is a major factor contributing to low baby birth weight and severe neonatal conditions.

In NFHS-5, the perinatal mortality rate for women under 20 years at the time of birth is estimated at 42.3 per 1,000 births. This is the sum of the number of stillbirths and early neonatal deaths for the 5-year period preceding the latest survey, divided by the number of pregnancies of 7+ months. In addition, these young mothers were more likely to face complications like massive vaginal bleeding (24.3%) compared to older mothers.

Teenaged mothers are also less likely to pay heed to birth intervals. The median birth interval in the 15-19 age group is just 21 months, while the country average is 32.7 months. Short birth intervals (<24 months) are associated with increased health risks to mother and baby. The under-five mortality rate for children born less than 2 years after the preceding birth is more than twice as high as that for children born three years apart.

Impacting India’s future

Adolescent fertility is not just an individual household’s problem; it holds the key to India’s future development. “Teenage mothers are less likely to continue going to school, which prevents them from realising their full potential and finding better economic opportunities, and often results in reduced lifetime earnings,” says the World Bank, adding that adolescent pregnancy can also affect future generations.

For example, there are multiple studies proving that daughters and sisters of teenage mothers are at a greater risk of teenage pregnancy themselves, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty.

Childbearing, age of mother at

1992-2021

Rema Nagarajan, July 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 6, 2023: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 6, 2023: The Times of India

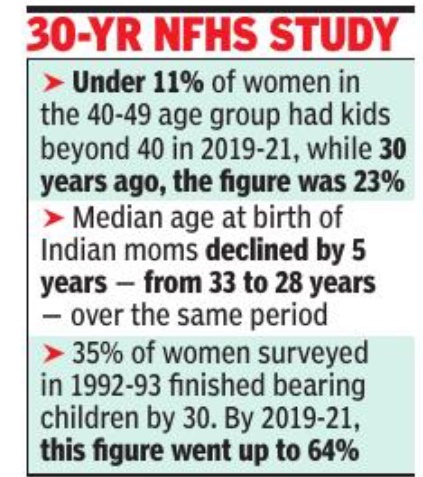

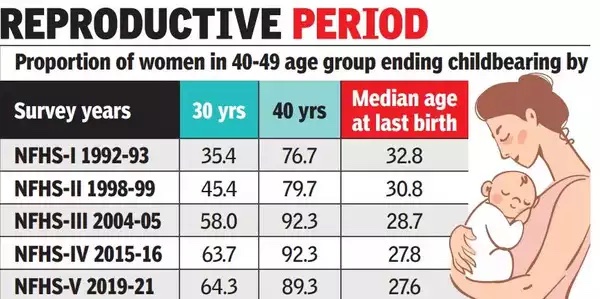

Over the last 30 years, India has witnessed a shortening of women’s reproductive period as they are ending childbearing at an earlier age than they did in the past. A comparison of data from the first National Family Health Survey (NFHS) in 1992-93 with the latest (2019-21) shows that a little under 11% of women in the 40-49 age group had children beyond the age of 40, while 30 years ago, that proportion was over 23%. The median age at birth has declined by five years, from 33 years to 28 years, over the same period.

The study by researchers of the International Institute for Population Studies, which conducts the NFHS, was published recently in the journal ‘Nature’. The study shows while 35% women surveyed in 1992-93 had completed bearing children by 30, by 2019-21, this proportion went up to 64%.

Interestingly, the proportion of women who ended childbearing by 40 was slightly lower in 2019-21 than in the previous two NFHS. One of the authors of the study, Chander Shekhar explained that this was due to two reasons. First, with women often having the first child at an older age than in the past, in cases where they have more than one child, the second child would also come later. Also, with fertility treatment becoming more common, child birth could happen late since the treatment can take time.

Though the mean age at last birth ranged from 26 years in Tamil Nadu to 33 years in Meghalaya during NFHS-III (2004-05), in the next two surveys Andhra Pradesh had the lowest (about 25) and Meghalaya (over 30) showed the highest mean age at last birth.

The study found that the age at last birth was higher among women who got married before 15 years of age, women who had a higher number of births where pregnancies lasted at least 24 months, and among Muslim women.

“Pressure to have a child immediately after marriage and little control over their reproductive rights among uneducated women leads to higher rates of unintended pregnancies and continued childbearing at higher ages,” stated the study noting that even women with low levels of education had better access to and knowledge about contraception. Studies based on labour-force participation and fertility indicate that women with long work histories bear children later than those with little or no work experience, it added.

Although the focus of policy has mostly been on the need to delay the age at first childbirth, the age at last childbirth also plays an important role in the health of women and their children, noted the study. It pointed out that many studies have reported higher incidence of pre-term birth, intra-uterine growth restriction, fetal malformation and neonatal deaths among children born to older mothers. It added that women having a pregnancy at older ages are at higher risk of pregnancy complications, including maternal mortality and severe morbidities.

“The evidence indicates that during the 1970s, the age at first birth was deficient, and women started childbearing at very early ages with the average age at last birth ranging from 39 to 42 years, resulting in higher fertility levels. However, in recent years, most nations have seen a decrease in the number of young women giving birth, which has been driven by increased educational attainment, family planning methods, and behavioural changes,” stated the study.

STATE-WISE

Delhi

2016: teenage pregnancies, maternal mortality

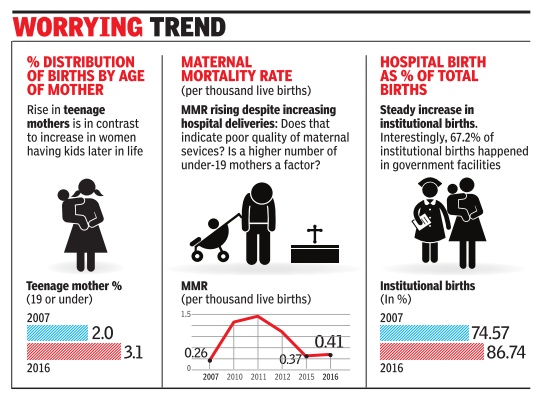

See graphic.

Durgesh Nandan Jha,3 out of 100 mothers 19 yrs or below, August 3, 2017: The Times of India

Ironically, Number Of Children Dying Before Turning One Shows A Decline

Maternal mortality rates in Delhi have increased marginally--from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2015 to 0.41 in 2016. In another worrying trend, the percentage of teenage pregnancies has gone up significantly . According to government data, three out of every 100 women (3.10%), who delivered kids in Delhi in 2016, were 19 years and below. The percentage of women from this age group delivering kids stood at 2.75, 1.93, 2.03 and 2.21 in 2015, 2014, 2013 and 2012, respectively .

Dr Alka Kriplani, professor and head of obstetrics and gynaecology division at AIIMS, said lack of education and poor knowledge about the use of contraceptive methods is the main reason behind the increase in teenage pregnancy .

“Younger women are at a higher risk of developing anaemia and hypertension if they get pregnant. It increases the risk of mortality too,“ she said.Another gynaecologist said that teenagers from sound economic background are able to get abortion done for unwanted pregnancy , but those from poor families often have to car ry through the motherhood risking their own life.

“Some girls do not know how to avoid getting pregnant: sex education is lacking. They may feel inhibited or ashamed to seek contraception services,“ states the World Health Organisation (WHO). It adds that reducing marriage before the age of 18 and creating understanding and support to reduce pregnancy before the age of 20 can help prevent teenage pregnancy .

On the brighter side, the Delhi government's birth and death registration data shows significant reduction in infant mortality rate (IMR), children who die before turning a year old. IMR in Delhi has gone down from 23.25 per 1,000 live births in 2015 to 21.35 in 2016. It is the lowest since 2009s when IMR was recorded at 18.96, officials said.

Deputy chief minister Manish Sisodia, while releasing the data on Wednesday , said 3,79,161 births were registered in Delhi in 2016 compared with 3,74,012 in 2015 and 3,73,693 a year ago. Sisodia said institutional births increased from 84.41% in 2015 to 86.74% in 2016.Age-group of the mother at the time of delivery reveals that in maximum (43.58%) cases, it was 20-24 years followed by 36.52% cases in 25-29 age-group and in 16.8% cases, the age of mother was more than 30 years, the deputy CM said.

=Teenaged mothers/ teenaged motherhood/ adolescent pregnancies=