Nair/ Nayar

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Contents |

Nāyar

Several distinct occupations call themselves Nair

The Nāyars,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes,49 “are a Dravidian caste, or rather a community, for we find several distinct elements with totally different occupations among the people who call themselves by this title. The original Nāyars were undoubtedly a military body, holding lands and serving as a militia, but the present Nāyar caste includes persons who, by hereditary occupation, are traders, artisans, oilmongers, palanquin-bearers, and even barbers and washermen. The fact seems to be that successive waves of immigration brought from the Canarese and Tamil countries different castes and different tribes; and these, settling down in the country, adopted the customs and manners, and assumed the caste names of the more respectable of the community that surrounded them. This process of assimilation is going on even yet.

Evolution into Nayars

Chettis of Coimbatore, for example, who settled in Palghāt and Valluvanād within living memory, have developed by this time into Nāyars. In the census schedules we find instances in which the males of a house affix the term Nāyar to their names, while the names of the females end in Chettichi. Gollas entering the country from the north have similarly, in course of time, assumed Nāyar customs and manners, and are now styled Nāyars. Again the rājahs and chieftains of the country sometimes raised individuals or classes who had rendered them meritorious service to the rank of Nāyars. These men were thereafter styled Nāyars, but formed a separate sub-division with little or no communion with the rest of the Nāyar class, until at least, after the lapse of generations, when their origin was forgotten. Nāyar may thus at present be considered to be a term almost as wide and general as Sūdra.”

Offspring of Nambūdri men with Dēva, Gandharva and Rakshasa women?

According to the Brāhman tradition, the Nāyar caste is the result of union between the Nambūdris with Dēva, Gandharva and Rakshasa women introduced by Parasurāma; and this tradition embodies the undoubted fact that the caste by its practice of hypergamy has had a very large infusion of Aryan blood. In origin the Nāyars were probably a race of Dravidian immigrants, who were amongst the first invaders of Malabar, and as conquerors assumed the position of the governing and [285]land-owning class. The large admixture of Aryan blood combined with the physical peculiarities of the country would go far to explain the very marked difference between the Nāyar of the present day and what may be considered the corresponding Dravidian races in the rest of the Presidency.50

Protectors of the State

In connection with the former position of the Nāyars as protectors of the State, it is noted by Mr. Logan51 that “in Johnston’s ‘Relations of the most famous Kingdom in the world’ (1611), there occurs the following quaintly written account of this protector guild. ‘It is strange to see how ready the Souldiour of this country is at his Weapons: they are all gentile men, and tearmed Naires. At seven Years of Age they are put to School to learn the Use of their Weapons, where, to make them nimble and active, their Sinnewes and Joints are stretched by skilful Fellows, and annointed with the Oyle Sesamus [gingelly: Sesamum indicum]: By this annointing they become so light and nimble that they will winde and turn their Bodies as if they had no Bones, casting them forward, backward, high and low, even to the Astonishment of the Beholders. Their continual Delight is in their Weapon, perswading themselves that no Nation goeth beyond them in Skill and Dexterity.’ And Jonathan Duncan, who visited Malabar more than once as one of the Commissioners from Bengal in 1792–93, and afterwards as Governor of Bombay, after quoting the following lines from Mickle’s Camoens, Book VII—

’Poliar the labouring lower clans are named:

By the proud Nayrs the noble rank is claimed;

The toils of culture and of art they scorn:

The shining faulchion brandish’d in the right—

Their left arm wields the target in the fight’—

went on to observe: ‘These lines, and especially the two last, contain a good description of a Nayr, who walks along, holding up his naked sword with the same kind of unconcern as travellers in other countries carry in their hands a cane or walking staff. I have observed others of them have it fastened to their back, the hilt being stuck in their waist band, and the blade rising up and glittering between their shoulders’ (Asiatic Researches, V. 10, 18). M. Mahé de la Bourdonnais, who had some experience of their fighting qualities in the field, thus described them: ‘Les Nairs sont de grands hommes basanés, légers, et vigoureux: Ils n’ont pas d’autre profession que celle des armes, et seraient de fort bons soldats, s’ils étiaent disciplinés: mais ils combattent sans ordre, ils prennent la fuite dès qu’on les serre de près avec quelque supèrioritê; pourtant, s’ils se voient pressés avec vigueur et qu’ils se croient en danger, ils reviennent à la charge, et ne se rendent jamais’ (M. Esquer, Essai sur les Castes dans l’Inde, page 181).

Their modes of fighting

Finally, the only British General of any note—Sir Hector Munro—who had ever to face the Nāyars in the field, thus wrote of their modes of fighting:—

‘One may as well look for a needle in a Bottle of Hay as any of them in the daytime, they being lurking behind sand banks and bushes, except when we are marching towards the Fort, and then they appear like bees out in the month of June.’ ‘Besides which,’ he continued, ‘they point their guns well, and fire them well also.’ (Tellicherry Factory Diary, March, 1761). They were, in short, brave light troops, excellent in skirmishing, but their organization into small bodies with discordant interests unfitted them to repel any serious invasion by an enemy even moderately well organised. Among other strange Malayāli customs, Sheikh [287]Zin-ud-din52 noticed the fact that, if a chieftain was slain, his followers attacked and obstinately persevered in ravaging the slayer’s country, and killing his people till their vengeance was satisfied. This custom is doubtless that which was described so long ago as in the ninth century A.D. by two Muhammadans, whose work was translated by Renaudot (Lond., 1733).

‘There are kings who, upon their accession, observe the following ceremony. A quantity of cooked rice was spread before the king, and some three or four hundred persons came of their own accord, and received each a small quantity of rice from the king’s own hands after he himself had eaten some. By eating of this rice they all engage themselves to burn themselves on the day the king dies or is slain, and they punctually fulfil their promise.’ Men, who devoted themselves to certain death on great occasions, were termed Amoucos by the Portuguese; and Barbosa, one of the Portuguese writers, alluded to the practice as prevalent among the Nāyars. Purchas has also the following:—‘The king of Cochin hath a great number of Gentlemen, which he calleth Amocchi, and some are called Nairi: these two sorts of men esteem not their lives anything, so that it may be for the honour of the king.’ The proper Malayālam term for such men was Chāver, literally those who took up, or devoted themselves to death. It was a custom of the Nāyars, which was readily adopted by the Māppillas, who also at times—as at the great Mahāmakkam, twelfth year feast, at Tirunāvāyi53—devoted themselves to death in the company of Nāyars for the honour of the Valluvanad Rāja. And probably the frantic fanatical rush of the Māppillas on British bayonets, which is not even yet a thing of the past, is the latest development of this ancient custom of the Nāyars. The martial spirit of the Nāyars in these piping times of peace has quite died out for want of exercise. The Nāyar is more and more becoming a family man. Comparatively few of them now-a-days even engage in hunting.” According to an inscription of the King Kulōttunga I (A.D. 1083–84), he conquered Kudamalai-Nadu, i.e., the western hill country (Malabar), whose warriors, the ancestors of the Nāyars of the present day, perished to the last man in defending their independence.54

Nairs are the gentry

The following description of the Nāyars at the beginning of the sixteenth century is given by Duarte Barbosa.55 “The Nairs are the gentry, and have no other duty than to carry on war, and they continually carry their arms with them, which are swords, bows, arrows, bucklers, and lances. They all live with the kings, and some of them with other lords, relations of the kings, and lords of the country, and with the salaried governors, and with one another. They are very smart men, and much taken up with their nobility.... These Nairs, besides being all of noble descent, have to be armed as knights by the hand of a king or lord with whom they live, and until they have been so equipped they cannot bear arms nor call themselves Nairs....

Schooling

In general, when they are seven years of age, they are immediately sent to school to learn all manner of feats of agility and gymnastics for the use of their weapons. First they learn to dance and then to tumble, and for that purpose they render supple all their limbs from their childhood, so that they can bend them in any direction.... These Nairs live outside the towns separate from other people on their estates which are fenced in. When they go anywhere, they shout to the peasants, that they may get out of the way where they have to pass; and the peasants do so, and, if they did not do it, the Nairs might kill them without penalty. And, if a peasant were by misfortune to touch a Nair lady, her relations would immediately kill her, and likewise the man that touched her and all his relations. This, they say, is done to avoid all opportunity of mixing the blood with that of the peasants.... These are very clean and well-dressed women, and they hold it in great honour to know how to please men. They have a belief amongst them that the woman who dies a virgin does not go to paradise.”

Writing in the eighteenth century, Hamilton states56 that “it was an ancient custom for the Samorin (Zamorin) to reign but twelve years, and no longer. If he died before his term was expired, it saved him a troublesome ceremony of cutting his own throat on a public scaffold erected for that purpose. He first made a feast for all his nobility and gentry, who were very numerous. After the feast he saluted his guests, went on the scaffold, and very neatly cut his own throat in the view of the assembly. His body was, a little while after, burned with great pomp and ceremony, and the grandees elected a new Samorin. Whether that custom was a religious or a civil ceremony I know not, but it is now laid aside, and a new custom is followed by the modern Samorin, that a jubilee is proclaimed throughout his dominion at the end of twelve years, and a tent is pitched for him in a spacious plain, and a great feast is celebrated for ten or twelve days with mirth and jollity, guns firing night and day, so at the end of the feast any four of the guests that have a mind to gain a crown by a desperate action in fighting their way through thirty or forty thousand of his guards, and kill the Samorin in his tent, he that kills him succeeds him in his empire.

In Anno 1695 one of these jubilees happened, and the tent pitched near Ponnany, a sea-port of his about fifteen leagues to the southward of Calicut. There were but three men that would venture on that desperate action, who fell on, with sword and target, among the guards, and, after they had killed and wounded many, were themselves killed. One of the desperadoes had a nephew of fifteen or sixteen years of age that kept close by his uncle in the attack on the guards, and, when he saw him fall, the youth got through the guards into the tent, and made a stroke at his Majesty’s head, and had certainly dispatched him if a large brass lamp which was burning over his head had not marred the blow, but, before he could make another, he was killed by the guards, and I believe the same Samorin reigns yet.”

It is noted by Sonnerat57 that the Nāyars “are the warriors; they have also the privilege of enjoying all the women of their caste. Their arms, which they constantly carry, distinguish them from the other tribes. They are besides known by their insolent haughtiness. When they perceive pariahs, they call out to them, even at a great distance, to get out of their way, and, if any one of these unfortunate people approaches too near a Nair, and through inadvertence touches him, the Nair has a right to murder him, which is looked upon as a very innocent action, and for which no complaint is ever made. It is true that the pariahs have one day in the year when all the Nairs they can touch become their slaves, but the Nairs take such precautions to keep out of the way at the time, that an accident of that kind seldom happens.” It is further recorded by Buchanan58 that “the whole of these Nairs formed the militia of Malayala, directed by the Namburis and governed by the Rajahs. Their chief delight is in arms, but they are more inclined to use them for assassination or surprise, than in the open field. Their submission to their superiors was great, but they exacted deference from those under them with a cruelty and arrogance, rarely practised but among Hindus in their state of independence. A Nair was expected to instantly cut down a Tiar or Mucuai, who presumed to defile him by touching his person; and a similar fate awaited a slave, who did not turn out of the road as a Nair passed.”

Origin

Nāyar is commonly said to be derived from the Sanskrit Nāyaka, a leader, and to be cognate with Naik, and Nayudu or Naidu. In this connection, Mr. L. Moore writes59 that “if a reference is made to the Anglo-Indian Glossary (Hobson-Jobson) by Yule and Burnell, it will be found that the term Naik or Nayakan, and the word Nayar are derived from the same Sanskrit original, and there is a considerable amount of evidence to show that the Nayars of Malabar are closely connected by origin with the Nayakans of Vijayanagar.60 Xavier, writing in 1542 to 1544, makes frequent references to men whom he calls Badages, who are said to have been collectors of royal taxes, and to have grievously oppressed Xavier’s converts among the fishermen of Travancore.61 Dr. Caldwell, alluding to Xavier’s letters, says62 that these Badages were no doubt Vadages or men from the North, and is of opinion that a Jesuit writer of the time who called them Nayars was mistaken, and that they were really Nayakans from Madura.

I believe, however, that the Jesuit rightly called them Nayars, for I find that Father Organtino, writing in 1568, speaks of these Badages as people from Narasinga (a kingdom north of Madura, lying close to Bishnaghur).63 Bishnaghur is, of course, Vijayanagar, and the kingdom of Narasinga was the name frequently given by the Portuguese to Vijayanagar. Almost every page of Mr. Sewell’s interesting book on Vijayanagar bears testimony to the close connection between Vijayanagar and the West Coast. Dr. A. C. Burnell tells us that the kings who ruled Vijayanagar during the latter half of the fourteenth century belonged to a low non-Aryan caste, namely, that of Canarese cow-herds.64 They were therefore closely akin to the Nayars, one of the leading Rajas among whom at the present time, although officially described as a Samanta, is in reality of the Eradi, i.e., cow-herd caste.65 It is remarkable that Colonel (afterwards Sir Thomas) Munro, in the memorandum written by him in 180266 on the Poligars of the Ceded Districts, when dealing with the cases of a number of Poligars who were direct descendants of men who had been chiefs under the kings of Vijayanagar, calls them throughout his report Naique or Nair, using the two names as if they were identical. Further investigation as to the connection of the Nayars of Malabar with the kingdom of Vijayanagar would, I believe, lead to interesting results.” In the Journal of the Hon. John Lindsay (1783) it is recorded67 that “we received information that our arms were still successful on the Malabar coast, and that our army was now advancing into the inland country; whilst the Nayars and Polygars that occupy the jungles and mountains near Seringapatam, thinking this a favourable opportunity to regain their former independence, destroyed the open country, and committed as many acts of barbarity as Hyder’s army had done in the Carnatic.”

“Some,” Mr. N. Subramani Aiyar writes in a note on the Nāyars of Travancore, “believe that Nāyar is derived from Nāga (serpents), as the Aryans so termed the earlier settlers of Malabar on account of the special adoration which they paid to snakes. The Travancore Nāyars are popularly known as Malayāla Sūdras—a term which contrasts them sharply with the Pāndi or foreign Sūdras, of whom a large number immigrated into Travancore in later times. Another name by which Nāyars are sometimes known is Malayāli, but other castes, which have long inhabited the Malayālam country, can lay claim to this designation with equal propriety. The most general title of the Nāyars is Pillai (child), which was once added to the names of the Brāhman dwellers in the south. It must, in all probability, have been after the Brāhmans changed their title to Aiyar (father), by which name the non-Brāhman people invariably referred to them, that Sūdras began to be termed Pillai.

We find that the Vellālas of the Tamil country and the Nāyars of Travancore called themselves Pillai from very early times. The formal ceremony of paying down a sum of money, and obtaining a distinction direct from the Sovereign was known as tirumukham pitikkuka, or catching the face of the king, and enabled the recipients to add, besides the honorary suffix Pillai, the distinctive prefix Kanakku, or accountant, to their name. So important were the privileges conferred by it that even Sanku Annavi, a Brāhman Dalava, obtained it at the hand of the reigning Mahārāja, and his posterity at Vempannūr have enjoyed the distinction until the present day. The titles Pillai and Kanakku are never used together. The name of an individual would be, for example, either Krishna Pillai or Kanakku Rāman Krishnan, Rāman being the name of the Karanavan or the maternal uncle. A higher title, Chempakaraman, corresponds to the knighthood of mediæval times, and was first instituted by Mahārāja Marthanda Varma in memory, it is said, of his great Prime Minister Rāma Aiyyan Dalawa.

Honouring the Nayars

The individual, whom it was the king’s pleasure to honour, was taken in procession on the back of an elephant through the four main streets of the fort, and received by the Prime Minister, seated by his side, and presented with pānsupāri (betel). Rare as this investiture is in modern times, there are many ancient houses, to which this title of distinction is attached in perpetuity. The title Kanakku is often enjoyed with it, the maternal uncle’s name being dropped, e.g., Kanakku Chempakaraman Krishnan. Tambi (younger brother) is another title prevalent in [295]Travancore. It is a distinctive suffix to the names of Nāyar sons of Travancore Sovereigns. But, in ancient times, this title was conferred on others also, in recognition of merit. Tambis alone proceed in palanquins, and appear before the Mahārāja without a head-dress. The consorts of Mahārājas are selected from these families. If a lady from outside is to be accepted as consort, she is generally adopted into one of these families. The title Karta, or doer, appears also to have been used as a titular name by some of the rulers of Madura. [At the Madras census, 1901, Kartākkal was returned by Balijas claiming to be descendants of the Nāyak kings of Madura and Tanjore.] The Tekkumkur and Vadakkumkur Rājas in Malabar are said to have first conferred the title Karta on certain influential Nāyar families.

In social matters the authority of the Karta was supreme, and it was only on important points that higher authorities were called on to intercede. All the Kartas belong to the Illam sub-division of the Nāyar caste. The title Kuruppu, though assumed by other castes than Nāyars, really denotes an ancient section of the Nāyars, charged with various functions. Some were, for instance, instructors in the use of arms, while others were superintendents of maid-servants in the royal household. Writing concerning the Zamorin of Calicut about 1500 A.D., Barbosa states that “the king has a thousand waiting women, to whom he gives regular pay, and they are always at the court to sweep the palaces and houses of the king, and he does this for the State, because fifty would be enough to sweep.” When a Mahārāja of Travancore enters into a matrimonial alliance, it is a Kuruppu who has to call out the full title of the royal consort, Panappillai Amma, after the presentation of silk and cloth has been performed.

The title Panikkar is derived from pani, work. [296]It was the Panikkars who kept kalaris, or gymnastic and military schools, but in modern times many Panikkars have taken to the teaching of letters. Some are entirely devoted to temple service, and are consequently regarded as belonging to a division of Mārans, rather than of Nāyars. The title Kaimal is derived from kai, hand, signifying power. In former times, some Kaimals were recognised chieftains, e.g., the Kaimal of Vaikkattillam in North Travancore. Others were in charge of the royal treasury, which, according to custom, could not be seen even by the kings except in their presence. “Neither could they,” Barbosa writes, “take anything out of the treasury without a great necessity, and by the counsel of this person and certain others.” The titles Unnithan and Valiyathan were owned by certain families in Central Travancore, which were wealthy and powerful. They were to some extent self-constituted justices of the peace, and settled all ordinary disputes arising in the kara where they dwelt. The title Menavan, or Menon, means a superior person, and is derived from mel, above, and avan he. The recipient of the title held it for his lifetime, or it was bestowed in perpetuity on his family, according to the amount of money paid down as atiyara. As soon as an individual was made a Menon, he was presented with an ola (palmyra leaf for writing on) and an iron style as symbols of the office of accountant, which he was expected to fill. In British Malabar even now every amsam or revenue village has an accountant or writer called Menon. The title Menokki, meaning one who looks over or superintends, is found only in British Malabar, as it was exclusively a creation of the Zamorin. [They are, I gather, accountants in temples.]

Sub-divisions

“There are numerous sub-divisions comprised under the general head Nāyar, of which the most important, mentioned in vernacular books, are Kiriyam, Illam, Svarupam, Itacheri or Idacheri, Pallichan, Ashtikkurichchi, Vattakātan, Otatu, Pulikkal, Vyapari, Vilakkitalavan, and Veluthetan. Of these Ashtikkurichchi and Pulikkal are divisions of Mārān, Vyapari is a division of Chettis, and Vilakkitalavan and Veluthetan are barbers and washermen respectively.

“The chief divisions of Nāyars, as now recognised, are as follows:—

1. Kiriyam, a name said to be a corruption of the Sanskrit griha, meaning house. This represents the highest class, the members of which were, in former times, not obliged to serve Brāhmans and Kshatriyas.

2. Illakkar.—The word illam indicates a Nambūtiri Brāhman’s house, and tradition has it that every illam family once served an illam. But, in mediæval times, any Nāyar could get himself recognised as belonging to the Illam division, provided that a certain sum of money, called adiyara, was paid to the Government. The Illakkar are prohibited from the use of fish, flesh, and liquor, but the prohibition is not at the present day universally respected. In some parts of Malabar, they have moulded many of their habits in the truly Brāhmanical style.

3. Svarupakkar.—Adherents of the Kshatriya families of Travancore. The members of the highest group, Parūr Svarupam, have their purificatory rites performed by Mārāns. It is stated that they were once the Illakkar servants of one Karuttetathu Nambutiri, who was the feudal lord of Parūr, and afterwards became attached to the royal household which succeeded to that estate, thus becoming Parūr Svarupakkar.

4. Padamangalam and Tamil Padam were not originally Nāyars, but immigrants from the Tamil [298]country. They are confined to a few localities in Travancore, and until recently there was a distinctive difference in regard to dress and ornaments between the Tamil Padam and the ordinary Nāyars. The occupation of the Padamangalakkar is temple service, such as sweeping, carrying lamps during processions, etc. The Tamil Padakkar are believed to have taken to various kinds of occupation, and, for this reason, to have become merged with other sections.

5. Vāthi or Vātti.—This name is not found in the Jatinirnaya, probably because it had not been differentiated from Mārān. The word is a corruption of vāzhti, meaning praying for happiness, and refers to their traditional occupation. They use a peculiar drum, called nantuni. Some call themselves Daivampatis, or wards of God, and follow the makkathāyam system of inheritance (in the male line).

6. Itacheri or Idacheri, also called Pantaris in South Travancore. They are herdsmen, and vendors of milk, butter and curds. The name suggests a relation of some kind to the Idaiyan caste of the Tamil country.

7. Karuvelam, known also by other names, such as Kappiyara and Tiruvattar. Their occupation is service in the palace of the Mahārāja, and they are the custodians of his treasury and valuables. Fifty-two families are believed to have been originally brought from Kolathanād, when a member thereof was adopted into the Travancore royal family.

8. Arikuravan.—A name, meaning those who reduced the quantity of rice out of the paddy given to them to husk at the temple of Kazhayakkuttam near Trivandrum, by which they were accosted by the local chieftain.

9. Pallichchan.—Bearers of palanquins for Brāhmans and Malabar chieftains. They are also employed as their attendants, to carry their sword and shield before them.

10. Vandikkāran.—A name, meaning cartmen, for those who supply fuel to temples, and cleanse the vessels belonging thereto.

11. Kuttina.—The only heiress of a Svarupam tarwad is said to have been a maid-servant in the Vadakketam Brāhman’s house, and her daughter’s tāli-kettu ceremony to have been celebrated in her master’s newly-built cowshed. The bride was called kuttilachchi, or bride in a cowshed, and her descendants were named Kuttina Nāyars. They intermarry among themselves, and, having no priests of their own, obtain purified water from Brāhmans to remove the effects of pollution.

12. Matavar.—Also known as Puliyattu, Veliyattu, and Kāllur Nāyars. They are believed to have been good archers in former times.

13. Otatu, also called Kusa. Their occupation is to tile or thatch temples and Brāhman houses.

14. Mantalayi.—A tract of land in the Kalkulam taluk, called Mantalachchi Konam, was granted to them by the State. They are paid mourners, and attend at the Trivandrum palace when a death occurs in the royal family.

15. Manigrāmam.—Believed to represent Hindu recoveries from early conversion to Christianity. Manigrāmam was a portion of Cranganore, where early Christian immigrants settled.

16. Vattaykkatan, better known in Travancore as Chakala Nāyars, form in many respects the lowest sub-division. They are obliged to stand outside the sacrificial stones (balikallu) of a sanctuary, and are not allowed to take the title Pillai. Pulva is a title of distinction among them. One section of them is engaged [300]in the hereditary occupation of oil-pressing, and occupies a lower position in the social scale than the other.”

Clans and professions

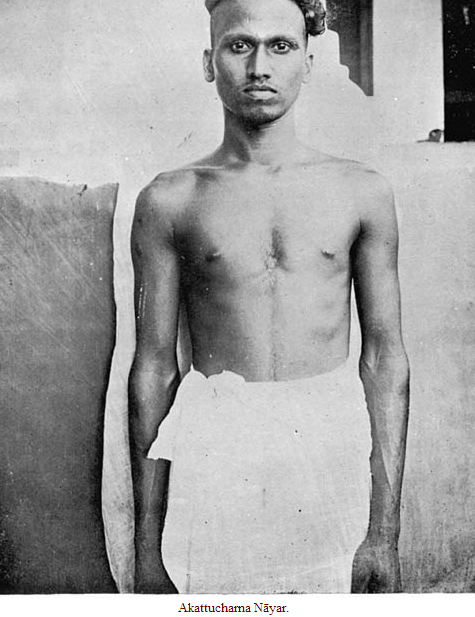

The following list of “clans” among the Nāyars of Malabar whom he examined anthropometrically is given by Mr. F. Fawcett68:—

Kiriyattil.

Sudra.

Kurup.

Nambiyar.

Urāli.

Nalliōden.

Viyyūr.

Akattu Charna.

Purattu Charna.

Vattakkād.

Vangilōth.

Kitāvu.

Pallichan.

Muppathināyiran.

Vīyāpāri or Rāvāri.

Attikurissi.

Manavalan.

Adungādi.

Adiōdi.

Amayengolam.

Inter-se hierarchies

“The Kurup, Nambiyar Viyyūr, Manavālan, Vengōlan, Nelliōden, Adungādi, Kitāvu, Adiōdi, Āmayengolam, all superior clans, belong, properly speaking, to North Malabar. The Kiriyattil, or Kiriyam, is the highest of all the clans in South Malabar, and is supposed to comprise, or correspond with the group of clans first named from North Malabar. The Akattu Charna clan is divided into two sub-clans, one of which looks to the Zamorin as their lord, and the other owns lordship to minor lordlings, as the Tirumulpād of Nilambūr. The former are superior, and a woman of the latter may mate with a man of the former, but not vice versâ. In the old days, every Nāyar chief had his Charnavar, or adherents. The Purattu Charna are the outside adherents, or fighters and so on, and the Akattu Charna are the inside adherents—clerks and domestics. The clan from which the former were drawn is superior to the latter.

The Urālis are said to have been masons; the Pallichans manchīl bearers.69 The Sūdra clan supplies female servants in the houses of Nambūdiris. The Vattakkād (or Chakkingal: chakku, oil press) clan, whose proper métier is producing gingelly or cocoanut oil with the oil-mill, is the lowest of all, excepting, I think, the Pallichan. Indeed, in North Malabar, I have frequently been told by Nāyars of the superior clans that they do not admit the Vattakkād to be Nāyars, and say that they have adopted the honorary affix Nāyars to their names quite recently. There is some obscurity as regards the sub-divisions of the Vattakkād clan. To the north of Calicut, in Kurumbranād, they are divided into the Undiātuna, or those who pull (to work the oil-machine by hand), and the Murivechchu-ātune, or those who tie or fasten bullocks, to work the oil-machine. Yet further north, at Tellicherry and thereabouts, there are no known sub-divisions, while in Ernād, to the eastward, the clan is divided into the Veluttātu (white) and Karuttātu (black).

The white have nothing to do with the expression and preparation of oil, which is the hereditary occupation of the black. The white may eat with Nāyars of any clan; the black can eat with no others outside their own clan. The black sub-clan is strictly endogamous; the other, the superior sub-clan, is not. Their women may marry men of any other clan, the Pallichchan excepted. Union by marriage, or whatever the function may be named, is permissible between most of the other clans, the rule by which a woman may never unite herself with her inferior being always observed. She may unite herself with a man of her own clan, or with a man of any superior clan, or with a Nambūtiri, an Embrāntiri, or any other Brāhman, [302]or with one of the small sects coming between the Brāhmans and the Nāyars. But she cannot under any circumstances unite herself with a man of a clan, which is inferior to hers. Nor can she eat with those of a clan inferior to her; a man may, and does without restriction.

Her children by an equal in race and not only in mere social standing, but never those by one who is racially inferior, belong to her taravād.70 The children of the inferior mothers are never brought into the taravād of the superior fathers, i.e., they are never brought into it to belong to it, but they may live there. And, where they do so, they cannot enter the taravād kitchen, or touch the women while they are eating. Nor are they allowed to touch their father’s corpse. They may live in the taravād under these and other disabilities, but are never of it. The custom, which permits a man to cohabit with a woman lower in the social scale than himself, and prohibits a woman from exercising the same liberty, is called the rule of anulōmam and pratilōmam. Dr. Gundert derives anulōmam from anu, with lōmam (rōmam), hair, or going with the hair or grain. So pratilōmam means going against the hair or grain. According to this usage, a Nāyar woman, consorting with a man of a higher caste, follows the hair, purifies the blood, and raises the progeny in social estimation. By cohabitation with a man of a lower division (clan) or caste, she is guilty of pratilōmam, and, if the difference of caste were admittedly great, she would be turned out of her family, to prevent the whole family being boycotted. A corollary of this custom is that a Nambūtiri Brāhman father cannot touch his own children by his Nāyar consort without bathing [303]afterwards to remove pollution.

The children in the marumakkatayam family belong, of course, to their mother’s family, clan, and caste. They are Nāyars, not Nambūtiris. The Nāyars of North Malabar are held to be superior all along the line, clan for clan, to those of South Malabar, which is divided from the north by the river Korapuzha, seven miles north of Calicut, so that a woman of North Malabar would not unite herself to a man of her own clan name of South Malabar. A Nāyar woman of North Malabar cannot pass northward beyond the frontier; she cannot pass the hills to the eastward; and she cannot cross the Korapuzha to the south. It is tabu. The women of South Malabar are similarly confined by custom, breach of which involves forfeiture of caste. To this rule there is an exception, and of late years the world has come in touch with the Malayāli, who nowadays goes to the University, studies medicine and law in the Presidency town (Madras), or even in far off England.

Women of the relatively inferior Akattu Charna clan are not under quite the same restrictions as regards residence as are those of most of the other clans; so, in these days of free communications, when Malayālis travel, and frequently reside far from their own country, they often prefer to select wives from this Akattu Charna clan. But the old order changeth everywhere, and nowadays Malayālis who are in the Government service, and obliged to reside far away from Malabar, and a few who have taken up their abode in the Presidency town, have wrenched themselves free of the bonds of custom, and taken with them their wives who are of clans other than the Akattu Charna. The interdiction to travel, and the possible exception to it in the case of Akattu Charna women, has been explained to me in this way. The Nāyar woman observes pollution for three days during [304]menstruation. While in her period, she may not eat or drink with any other member of the taravād, and on the fourth day she must be purified. Purification is known as māttu (change), and it is effected by the washerwoman, who, in some parts of South Malabar, is of the Mannān or Vannān caste, whose métier is to wash for the Nāyars and Nambūtiris, but who is, as a rule, the washerwoman of the Tīyan caste, giving her, after her bath, one of her own cloths to wear (māttu, change of raiment) instead of the soiled cloth, which she takes away to wash. Pollution, which may come through a death in the family, through child-birth, or menstruation, must be removed by māttu. Until it is done, the woman is out of caste. It must be done in the right way at the right moment, under pain of the most unpleasant social consequences. How that the influential rural local magnate wreaks vengeance on a taravād by preventing the right person giving māttu to the women is well known in Malabar. He could not, with all the sections of the Penal Code at his disposal, inflict greater injury. Now the Nāyar woman is said to feel compelled to remain in Malabar, or within her own part of it, in order to be within reach of māttu.

My informant tells me that, the Vannān caste being peculiar to Malabar, the Nāyar women cannot go where these are not to be found, and that māttu must be done by one of that caste. But I know, from my own observation in the most truly conservative localities, in Kurumbranād for example, where the Nāyar has a relative superiority, that the washerman is as a rule a Tīyan; and I cannot but think that the interdiction has other roots than those involved in māttu. It does not account for the superstition against crossing water, which has its counterparts elsewhere in the world. The origin of the interdiction to cross the river southwards has been explained to me as emanating from a command of the Kōlatirri Rājah in days gone by, when, the Arabs having come to the country about Calicut, there was a chance of the women being seized and taken as wives. The explanation is somewhat fanciful. The prohibition to cross the river to the northwards is supposed to have originated in much the same way.

As bearing on this point, I may mention that the Nāyar women living to the east of Calicut cannot cross the river backwater, and come into the town.” It may be noted in this connection that the Paikāra river on the Nīlgiri hills is sacred to the Todas, and, for fear of mishap from arousing the wrath of the river-god, a pregnant Toda woman will not venture to cross it. No Toda will use the river water for any purpose, and they do not touch it, unless they have to ford it. They then walk through it, and, on reaching the opposite bank, bow their heads. Even when they walk over the Paikāra bridge, they take their hands out of the putkuli (body-cloth) as a mark of respect.

The complexity of the sub-divisions among the Nāyars in North Malabar is made manifest by the following account thereof in the Gazetteer of Malabar. “There are exogamous sub-divisions (perhaps corresponding to original tarwāds) called kulams, and these are grouped to form the sub-castes which are usually endogamous. It is quite impossible to attempt a complete account of the scheme, but to give some idea of its nature one example may be taken, and dealt with in some detail; and for this purpose the portion of Kurumbranād known as Payyanād will serve. This is the country between the Kōttapuzha and Pōrapuzha rivers, and is said to have been given by a Rāja of Kurumbranād to a certain Ambādi Kōvilagam Tamburātti (the stānam or title of the senior lady of the Zāmorin Rāja’s family). In this tract or nād there were originally six stānis or chieftains, who ruled, under the Rāja, with the assistance, or subject to the constitutional control, of four assemblies of Nāyars called Kūttams. Each kūttam had its hereditary president.

Kulams

In this tract there are seven groups of kulams. The highest includes twelve kulams, Vengalat, Pattillat, Vīyyūr, Nelliōt, Atunkudi, Amayangalat, Nellōli, Nilanchēri, Rendillat, Pulliyāni, Orakātteri, and Venmēri. Of these, the Pattillat and Rendillat (members of the ten and members of the two illams or houses) affix the title Adiyōdi to their names, the last three affix the title Nambiyar, and the rest affix Nāyar. Of the six stānis already mentioned, three, with the title of Adiyōdi, belong to the Vengalat kulam, while two of the presidents of kūttams belonged to the Pattillat kulam. The younger members of the stāni houses are called kidavu. It is the duty of women of Viyyūr and Nelliōt kulams to join in the bridal procession of members of the Vengalat kulam, the former carrying lamps, and the latter salvers containing flowers, while the Rendillat Adiyōdis furnish cooks to the same class. Pattillat Adiyōdis and Orakātteri Nambiyars observe twelve days’ pollution, while all the other kulams observe fifteen. The second group consists of six kulams, Eravattūr, Ara-Eravattūr (or half Eravattūr), and Attikōdan Nāyars, Tonderi Kidāvus, Punnan Nambiyars, and Mēnōkkis. All these observe fifteen days’ pollution. The third group consists of three kulams, Tacchōli to which the remaining three stānis belong, Kōthōli, and Kuruvattānchēri.

All affix Nāyar to their names, and observe fifteen days’ pollution. The fourth group consists of three kulams, Peruvānian Nambiyars, Chellādan Nāyars, and Vennapālan Nāyars. All three observe fifteen days’ pollution. The name Peruvānian means great or principal oil-man; and it is the duty of this caste to present the Kurumbranād Rāja with oil on the occasion of his formal installation. The fifth group consists of the three kulams, Mannangazhi, Paramchela, and Pallikara Nāyars, all observing fifteen days’ pollution. A member of the first-named class has to place an āmanapalaga (the traditional seat of Nambūdiris and other high castes) for the Kurumbranād Rāja to sit on at the time of his installation, while a member of the second has to present him with a cloth on the same occasion. The sixth group consists of four kiriyams named Patam, Tulu, Manan, and Ottu respectively, and has the collective name of Rāvāri. The seventh group consists of six kulams, Kandōn, Kannankōdan, Kotta, Karumba, Kundakollavan, and Panakādan Nāyars. All observe fifteen days’ pollution, and the women of these six kulams have certain duties to perform in connection with the purification of women of the Vengalat, Pattillat, and Orakatteri kulams. Besides these seven groups, there are a few other classes without internal sub-divisions. One such class is known as Pāppini Nāyar. A woman of this class takes the part of the Brāhmini woman (Nambissan) at the tāli-kettu kalyanam of girls belonging to the kulams included in the third group. Another class called Pālattavan takes the place of the Attikurissi Nāyar at the funeral ceremonies of the same three kulams.”

Polyandry in by-gone days

In illustration of the custom of polyandry among the Nāyars of Malabar in by-gone days, the following extracts may be quoted. “On the continent of India,” it is recorded in Ellis’ edition of the Kural, “polyandry is still said to be practiced in Orissa, and among particular tribes in other parts. In Malayālam, as is well known, the vision of Plato in his ideal republic is more completely realised, the women among the Nāyars not being restricted to family or number, but, after she has been consecrated by the usual rites before the nuptial fire, in which ceremony any indifferent person may officiate as the representative of her husband, being in her intercourse with the other sex only restrained by her inclinations; provided that the male with whom she associates be of an equal or superior tribe.

But it must be stated, for the glory of the female character, that, notwithstanding the latitude thus given to the Nāyattis, and that they are thus left to the guidance of their own free will and the play of their own fancy (which in other countries has not always been found the most efficient check on the conduct of either sex), it rarely happens that they cohabit with more than one person at the same time. Whenever the existing connexion is broken, whether from incompatibility of temper, disgust, caprice, or any of the thousand vexations by which from the frailty of nature domestic happiness is liable to be disturbed, the woman seeks another lover, the man another mistress. But it mostly happens that the bond of paternity is here, as elsewhere, too strong to be shaken off, and that the uninfluenced and uninterested union of love, when formed in youth, continues even in the decline of age.”

In a note on the Nāyars in the sixteenth century, Cæsar Fredericke writes as follows.71 “These Nairi having their wives common amongst themselves, and when any of them goe into the house of any of these women, he leaveth his sworde and target at the door, and the time that he is there, there dare not be any so hardie as to come into that house. The king’s children shall not inherite the kingdom after their father, because they hold this opinion, that perchance they were not begotten of the king their father, but of some other man, therefore they accept for their king one of the sonnes of the king’s sisters, or of some other woman of the blood roiall, for that they be sure that they are of the blood roiall.”

In his “New Account of the East Indies, (1727)” Hamilton wrote: “The husbands,” of whom, he said, there might be twelve, but no more at one time, “agree very well, for they cohabit with her in their turns, according to their priority of marriage, ten days more or less according as they can fix a term among themselves, and he that cohabits with her maintains her in all things necessary for his time, so that she is plentifully provided for by a constant circulation. When the man that cohabits with her goes into her house he leaves his arms at the door, and none dare remove them or enter the house on pain of death. When she proves with child, she nominates its father, who takes care of his education after she has suckled it, and brought it to walk or speak, but the children are never heirs to their father’s estate, but the father’s sister’s children are.”

Writing in the latter half of the eighteenth century, Grose says72 that “it is among the Nairs that principally prevails the strange custom of one wife being common to a number; in which point the great power of custom is seen from its rarely or never producing any jealousies or quarrels among the co-tenants of the same woman. Their number is not so much limited by any specific law as by a kind of tacit convention, it scarcely ever happening that it exceeds six or seven. The woman, however, is under no obligation to admit above a single attachment, though not less respected for using her privilege to its utmost extent. If one of the husbands happens to come to the house when she is employed with another, he knows that circumstance by certain signals left at the door that his turn is not come, and departs very resignedly.” Writing about the same time, Sonnerat73 says that “these Brāhmans do not marry, but have the privilege of enjoying all the Nairesses. This privilege the Portuguese who were esteemed as a great caste, obtained and preserved, till their drunkenness and debauchery betrayed them into a commerce with all sorts of women.

The following right is established by the customs of the country. A woman without shame may abandon herself to all men who are not of an inferior caste to her own, because the children (notwithstanding what Mr. de Voltaire says) do not belong to the father, but to the mother’s brother; they become his legitimate heirs at their birth, even of the crown if he is king.” In his ‘Voyages and Travels’, Kerr writes as follows.74 “By the laws of their country these Nayres cannot marry, so that no one has any certain or acknowledged son or father; all their children being born of mistresses, with each of whom three or four Nayres cohabit by agreement among themselves. Each one of this cofraternity dwells a day in his turn with the joint mistress, counting from noon of one day to the same time of the next, after which he departs, and another comes for the like time. Thus they spend their time without the care or trouble of wives and children, yet maintain their mistresses well according to their rank. Any one may forsake his mistress at his pleasure; and, in like manner, the mistress may refuse admittance to any one of her lovers when she pleases.

These mistresses are all gentlewomen of the Nayre caste, and the Nayres, besides being prohibited from marrying, must not attach themselves to any woman of a different rank. Considering that there are always several men attached to one woman, the Nayres never look upon any of the children born of their mistresses as belonging to them, however strong a resemblance may subsist, and all inheritances among the Nayres go to their brothers, or the sons of their sisters, born of the same mothers, all relationship being counted only by female consanguinity and descent. This strange law prohibiting marriage was established that they might have neither wives nor children on whom to fix their love and attachment; and that, being free from all family cares, they might more willingly devote themselves entirely to warlike service.” The term son of ten fathers is used as a term of abuse among Nāyars to this day.75 Tīpū Sultān is said to have issued the following proclamation to the Nāyars, on the occasion of his visit to Calicut in 1788. “And, since it is a practice with you for one woman to associate with ten men, and you leave your mothers and sisters unconstrained in their obscene practices, and are thence all born in adultery, and are more shameless in your connections than the beasts of the field; I hereby require you to forsake these sinful practices, and live like the rest of mankind.”76

As to the present existence or non-existence of polyandry I must call recent writers into the witness-box. The Rev. S. Mateer, Mr. Fawcett writes,77 “informed me ten years ago—he was speaking of polyandry among the Nāyars of Travancore—that he had ‘known an instance of six brothers keeping two women, four husbands to one, and two to the other. In a case where two brothers cohabited with one woman, and one was converted to Christianity, the other brother was indignant at the Christian’s refusal to live any longer in this condition.’ I have not known an admitted instance of polyandry amongst the Nāyars of Malabar at the present day, but there is no doubt that, if it does not exist now (and I think it does here and there), it certainly did not long ago.” Mr. Gopal Panikkar says78 that “to enforce this social edict upon the Nairs, the Brāhmans made use of the powerful weapon of their aristocratic ascendancy in the country, and the Nairs readily submitted to the Brāhman supremacy. Thus it came about that the custom of concubinage, so freely indulged in by the Brāhmans with Nair women, obtained such firm hold upon the country that it has only been strengthened by the lapse of time. At the present day there are families, especially in the interior of the district, who look upon it as an honour to be thus united with Brāhmans. But a reaction has begun to take place against this feeling, and Brāhman alliances are invariably looked down upon in respectable Nair tarwads.

Marriage/ Malabar Marriage Act

This reactionary feeling took shape in the Malabar Marriage Act.” Mr. Justice K. Narayana Marar says: “There is nothing strange or to be ashamed of in the fact that the Nāyars were originally of a stock that practiced polyandry, nor if the practice continued till recently. Hamilton and Buchanan say that, among the Nāyars of Malabar, a woman has several husbands, but these are not brothers. These travellers came to Malabar in the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century. There is no reason whatever to suppose that they were not just recording what they saw. For I am not quite sure whether, even now, the practice is not lurking in some remote nooks and corners of the country.” Lastly, Mr. Wigram writes as follows.79 “Polyandry may now be said to be dead, and, although the issue of a Nāyar marriage are still children of their mother rather than of their father, marriage may be defined as a contract based on mutual consent, and dissoluble at will. It has been well said (by Mr. Logan) that nowhere is the marriage tie, albeit informal, more rigidly observed or respected than it is in Malabar: nowhere is it more jealously guarded, or its neglect more savagely avenged.”

In connection with the tāli-kattu kalyānam, or tāli-tying marriage, Mr. Fawcett writes that “the details of this ceremony vary in different parts of Malabar, but the ceremony in some form is essential, and must be performed for every Nāyar girl before she attains puberty.” For an account of this ceremony, I must resort to the evidence of Mr. K. R. Krishna Menon before the Malabar Marriage Commission.80

“The tāli-kattu kalyānam is somewhat analogous to what a dēva-dāsi (dancing-girl) of other countries (districts) undergoes before she begins her profession. Among royal families, and those of certain Edaprabhus, a Kshatriya, and among the Charna sect a Nedungādi is invited to the girl’s house at an auspicious hour appointed for the purpose, and, in the presence of friends and castemen, ties a tāli (marriage badge) round her neck, and goes away after receiving a certain fee for his trouble. Among the other sects, the horoscope of the girl is examined along with those of her enangan (a recognised member of one’s own class) families, and the boy whose horoscope is found to agree with hers is marked out as a fit person to tie the tāli, and a day is fixed for the tāli-tying ceremony by the astrologer, and information given to the Karanavan81 (senior male in a tarwad) of the boy’s family. The feast is called ayaniūnu, and the boy is thenceforth called Manavālan or Pillai (bridegroom). From the house in which the Manavālan is entertained a procession is formed, preceded by men with swords, and shields shouting a kind of war-cry.

In the meantime a procession starts from the girl’s house, with similar men and cries, and headed by a member of her tarwad, to meet the other procession, and, after meeting the Manavālan, he escorts him to the girl’s house. After entering the booth erected for the purpose, he is conducted to a seat of honour, and his feet are washed by the brother of the girl, who receives a pair of cloths. The Manavālan is then taken to the centre of the booth, where bamboo mats, carpets and white cloths are spread, and seated there. The brother of the girl then carries her from inside the house, and, after going round the booth three times, places her at the left side of the Manavālan. The father of the girl then presents new cloths tied in a kambli (blanket) to the pair, and with this new cloth (called manthravadi) they change their dress. The wife of the Karanavan of the girl’s tarwad, if she be of the same caste, then decorates the girl by putting on anklets, etc. The purōhit (officiating priest) called Elayath (a low class of Brāhmans) then gives the tāli to the Manavālan, and the family astrologer shouts muhurtham (auspicious hour), and the Manavālan, putting his sword on the lap, ties the tāli round the neck of the girl, who is then required to hold an arrow and a looking-glass in her hand. In rich families a Brāhmani sings certain songs intended to bless the couple. In ordinary families who cannot procure her presence, a Nāyar, versed in songs, performs the office.

The boy and girl are then carried by enangans to a decorated apartment in the inner part of the house, where they are required to remain under a sort of pollution for three days. On the fourth day they bathe in some neighbouring tank (pond) or river, holding each other’s hands. After changing their clothes they come home, preceded by a procession. Tom-toms (native drums) and elephants usually form part of the procession, and turmeric water is sprinkled. When they come home, all doors of the house are shut, and the Manavālan is required to force them open. He then enters the house, and takes his seat in the northern wing thereof. The aunt and female friends of the girl then approach, and give sweetmeats to the couple. The girl then serves food to the boy, and, after taking their meal together from the same leaf, they proceed to the booth, where a cloth is severed into two parts, and each part given to the Manavālan and girl separately in the presence of enangans and friends. The severing of the cloth is supposed to constitute a divorce.” “The tearing of the cloth,” Mr. Fawcett writes, “is confined to South Malabar. These are the essentials of the ceremony, an adjunct to which is that, in spite of the divorce, the girl observes death pollution when her Manavālan dies. The same Manavālan may tie the tāli on any number of girls, during the same ceremony or at any other time, and he may be old or young. He is often an elderly holy Brāhman, who receives a small present for his services. The girl may remove the tāli, if she likes, after the fourth day. In some parts of Malabar there is no doubt that the man who performs the rôle of Manavālan is considered to have some right to the girl, but in such case it has been already considered that he is a proper man to enter into sambandham with her.”

Of the tāli-kattu kalyānam in Malabar, the following detailed account, mainly furnished by an Urāli Nāyar of Calicut, is given in the Gazetteer of Malabar. “An auspicious time has to be selected for the purpose, and the preliminary consultation of the astrologer is in itself the occasion of a family gathering. The Manavālan or quasi-bridegroom is chosen at the same time. For the actual kalyānam, two pandals (booths), a small one inside a large one, are erected in front of the padinhātta macchu or central room of the western wing. They are decorated with cloth, garlands, lamps and palm leaves, and the pillars should be of areca palm cut by an Asāri on Sunday, Monday, or Wednesday. The first day’s ceremonies open with a morning visit to the temple, where the officiating Brāhman pours water sanctified by mantrams (religious formulæ), and the addition of leaves of mango, peepul and darbha, over the girl’s head. This rite is called kalasam maduga. The girl then goes home, and is taken to the macchu, where a hanging lamp with five wicks is lighted. This should be kept alight during all the days of the kalyānam.

The girl sits on a piece of pala (Alstonia scholaris) wood, which is called a mana. She is elaborately adorned, and some castes consider a coral necklace an essential. In her right hand she holds a vāalkannādi (brass hand mirror), and in her left a charakkal (a highly ornate arrow). In front of the girl are placed, in addition to the five-wicked lamp and nirachaveppu, a metal dish or talam of parched rice, and the eight lucky things known as ashtamangalyam. A woman, termed Brahmini or Pushpini, usually of the Nambissan caste, sits facing her on a three-legged stool (pidam), and renders appropriate and lengthy songs, at the close of which she scatters rice over her. About midday there is a feast, and in the evening songs in the macchu are repeated. Next morning, the ceremonial in the macchu is repeated for the third time, after which the paraphernalia are removed to the nearest tank or to the east of the household well, where the Pushpini sings once more, goes through the form of making the girl’s toilet, and ties a cocoanut frond round each of her wrists (kappōla). The girl has then to rise and jump over a kindi (vessel) of water with an unhusked cocoanut placed on the top, overturning it the third time. The party then proceed to the pandal, two men holding a scarlet cloth over the girl as a canopy, and a Chāliyan (weaver) brings two cloths (kōdi vastiram), which the girl puts on. In the evening, the previous day’s ceremonial is repeated in the macchu.

The third day is the most important, and it is then that the central act of the ceremony is performed. For this the girl sits in the inner pandal richly adorned. In some cases she is carried from the house to the pandal by her karnavan or brother, who makes a number of pradakshinams round the pandal (usually 3 or 7) before he places her in her seat. Before the girl are the various objects already specified, and the hymeneal ditties of the Pushpini open the proceedings. At the auspicious moment the Manavālan arrives in rich attire. He is often preceded by a sort of body guard with sword and shield who utter a curious kind of cry, and is met at the gate of the girl’s house by a bevy of matrons with lamps and salvers decorated with flowers and lights, called talams. A man of the girl’s family washes his feet, and he takes his seat in the pandal on the girl’s right. Sometimes the girl’s father at this stage presents new cloths (mantravādi or mantrokōdi) to the pair, who at once don them. The girl’s father takes the tāli, a small round plate of gold about the size of a two-anna bit, with a hole at the top, from the goldsmith who is in waiting, pays him for it,’ and gives it to the Manavālan. The karnavan or father of the girl asks the astrologer thrice if the moment has arrived, and, as he signifies his assent the third time, the Manavālan ties the tāli round the girl’s neck amidst the shouts of those present. The Manavālan carries the girl indoors to the macchu, and feasting brings the day to a close.

Tom-toming and other music are of course incessant accompaniments throughout as on other festal occasions, and the women in attendance keep up a curious kind of whistling, called kurava, beating their lips with their fingers. On the fourth day, girl and Manavālan go in procession to the temple richly dressed. The boy, carrying some sort of sword and shield, heads the party. If the family be one of position, he and the girl must be mounted on an elephant. Offerings are made, to the deity, and presents to the Brāhmans. They return home, and, as they enter the house, the Manavālan who brings up the rear is pelted by the boys of the party with plantains, which he wards off with his shield. In other cases, he is expected to make a pretence of forcing the door open. These two usages are no doubt to be classed with those marriage ceremonies which take the form of a contest between the bridegroom and the bride’s relatives, and which are symbolic survivals of marriage by capture. The Manavālan and the girl next partake of food together in the inner pandal—a proceeding which obviously corresponds to the ceremonious first meal of a newly-married couple. The assembled guests are lavishly entertained. The chief Kovilagans and big Nāyar houses will feed 1,000 Brāhmans as well as their own relations, and spend anything up to ten or fifteen thousand rupees on the ceremony.”

Concerning the tāli-kettu ceremony in Travancore Mr. N. Subramani Aiyar writes as follows. “After the age of eleven, a Nāyar girl becomes too old for this ceremony, though, in some rare instances, it is celebrated after a girl attains her age. As among other castes, ages represented by an odd number, e.g., seven, nine, and eleven, have a peculiar auspiciousness attached to them. Any number of girls, even up to a dozen, may go through the ceremony at one time, and they may include infants under one year—an arrangement prompted by considerations of economy, and rendered possible by the fact that no civil or religious right or liability is contracted as between the parties. The duty of getting the girls of the tarwad ‘married’ devolves on the karanavan, or in his default on the eldest brother, the father’s obligation being discharged by informing him that the time for the ceremony has arrived. The masters of the ceremonies at a Nāyar tāli-kettu in Travancore are called Machchampikkar, i.e., men in the village, whose social status is equal to that of the tarwad in which the ceremony is to be celebrated.

At a preliminary meeting of the Machchampikkar, the number of girls for whom the ceremony is to be performed, the bridegrooms, and other details are settled. The horoscopes are examined by the village astrologer, and those youths in the tarwads who have passed the age of eighteen, and whose horoscopes agree with those of the girls, are declared to be eligible. The ola (palm-leaf) on which the Kaniyan (astrologer) writes his decision is called the muhurta charutu, and the individual who receives it from him is obliged to see that the ceremony is performed on an auspicious day in the near future. The next important item is the fixing of a wooden post in the south-west corner or kannimula of the courtyard. At the construction of the pandal (booth) the Pidakakkar or villagers render substantial aid. The mandapa is decorated with ears of corn, and hence called katirmandapa. It is also called mullapandal. On the night of the previous day the kalati or Brāhman’s song is sung.

A sumptuous banquet, called ayaniunnu, is given at the girl’s house to the party of the young man. The ceremony commences with the bridegroom washing his feet, and taking his seat within the pandal. The girl meanwhile bathes, worships the household deity, and is dressed in new cloths and adorned with costly ornaments. A Brāhman woman ties a thread round the girl’s left wrist, and sings a song called Subhadraveli, which deals with the marriage by capture of Subhadra by Arjuna. Then, on the invitation of the girl’s mother, who throws a garland round his neck, the bridegroom goes in procession, riding on an elephant, or on foot. The girl’s brother is waiting to receive him at the pandal. A leading villager is presented with some money, as if to recompense him for the permission granted by him to commence the ceremony. The girl sits within the mandapa, facing the east, with her eyes closed.

The bridegroom, on his arrival, sits on her right. He then receives the minnu (ornament) from the Ilayatu priest, and ties it round the girl’s neck. A song is sung called ammachampattu, or the song of the maternal uncle. If there are several brides, they sit in a row, each holding in her hand an arrow and a looking-glass, and the ornaments are tied on their necks in the order of their ages. Unless enangans are employed, there is usually only one tāli-tier, whatever may be the number of girls. In cases where, owing to poverty, the expenses of the ceremony cannot be borne, it is simply performed in front of a Brāhman temple, or in the pandaramatam, or house of the village chieftain. In many North Travancore taluks the girl removes her tali as soon as she hears of the tali-tier’s death.” It is noted by the Rev. S. Mateer82 that “a Nair girl of Travancore must get married with the tāli before the age of eleven to avoid reproach from friends and neighbours. In case of need a sword may even be made to represent a bridegroom.” Sometimes, when a family is poor, the girl’s mother makes an idol of clay, adorns it with flowers, and invests her daughter with the tāli in the presence of the idol.

Tāli-kettu

In an account of the tāli-kettu ceremony, in the Cochin Census Report, 1901, it is stated that “the celebration of the ceremony is costly, and advantage is therefore taken of a single occasion in the course of ten or twelve years, at which all girls in a family, irrespective of their ages, and, when parties agree, all girls belonging to families that observe death pollution between one another go through the ceremony. The ceremony opens with the fixing of a post for the construction of a pandal or shed, which is beautifully decorated with cloth, pictures and festoons. The male members of the village are invited, and treated to a feast followed by the distribution of pān-supāri. Every time that a marriage ceremony is celebrated, a member of the family visits His Highness the Rāja with presents, and solicits his permission for the celebration. Such presents are often made to the Nambūdri Jenmis (landlords), by their tenants, and by castes attached to illams.

It may be noted that certain privileges, such as sitting on a grass mat, having an elephant procession, drumming, firing of pop-guns, etc., have often to be obtained from the Ruler of the State. The marriage itself begins with the procession to the marriage pandal with the eight auspicious things (ashtamangalyam) and pattiniruththal (seating for song), at the latter of which a Brāhmini or Pushpini sings certain songs based upon suitable Purānic texts. The girls and other female members of the family, dressed in gay attire and decked with costly ornaments, come out in procession to the pandal, where the Pushpini sings, with tom-toms and the firing of pop-guns at intervals. After three, five, or seven rounds of this, a cutting of the jasmine placed in a brass pot is carried on an elephant by the Elayad or family priest to the nearest Bhagavati temple, where it is planted on the night previous to the ceremonial day with tom-toms, fireworks, and joyous shouts of men and women. A few hours before the auspicious moment for the ceremony, this cutting is brought back. Before the tāli is tied, the girls are brought out of the room, and, either from the ground itself or from a raised platform, beautifully decorated with festoons, etc., are made to worship the sun.

The bridegroom, a Tirumulpād or an enangan, is then brought into the house with sword in hand, with tom-toms, firing of pop-guns, and shouts of joy. At the gate he is received by a few female members with ashtamangalyam in their hands, and seated on a bench or stool in the pandal. A male member of the family, generally a brother or maternal uncle of the girl, washes the feet of the bridegroom. The girls are covered with new cloths of cotton or silk, and brought into the pandal, and seated screened off from one another. After the distribution of money presents to the Brāhmans and the Elayad, the latter hands over the tāli, or thin plate of gold shaped like the leaf of aswatha (Ficus religiosa), and tacked on to a string, to the Tirumulpād, who ties it round the neck of the girl. A single Tirumulpād often ties the tāli round the neck of two, three, or four girls.

He is given one to eight rupees per girl for so doing. Sometimes the tāli is tied by the mother of the girl. The retention of the tāli is not at all obligatory, nay it is seldom worn or taken care of after the ceremony. These circumstances clearly show the purely ceremonial character of this form of marriage. The Karamel Asan, or headman of the village, is an important factor on this occasion. In a conspicuous part of the marriage pandal, he is provided with a seat on a cot, on which a grass mat, a black blanket, and white cloth are spread one over the other. Before the tāli is tied, his permission is solicited for the performance of the ceremony. He is paid 4, 8, 16, 32 or 64 puthans (a puthan = 10 pies) per girl, according to the means of the family. He is also given rice, curry stuff, and pān-supāri. Rose-water is sprinkled at intervals on the males and females assembled on the occasion. With the distribution of pān-supāri, scented sandal paste and jasmine flowers to the females of the village and wives of relatives and friends, who are invited for the occasion, these guests return to their homes.

The male members, one or two from each family in the village, are then treated to a sumptuous feast. In some places, where the Enangu system prevails, all members of such families, both male and female, are also provided with meals. On the third day, the villagers are again entertained to a luncheon of rice and milk pudding, and on the fourth day the girls are taken out in procession for worship at the nearest temple amidst tom-toms and shouting. After this a feast is held, at which friends, relatives, and villagers are given a rich meal. With the usual distribution of pān-supāri, sandal and flowers, the invited guests depart. Presents, chiefly in money, are made to the eldest male member of the family by friends and relatives and villagers, and with this the ceremony closes. From the time of fixing the first pole for the pandal to the tying of the tāli, the village astrologer is in attendance on all ceremonial occasions, as he has to pronounce the auspicious moment for the performance of each item.

During the four days of the marriage, entertainments, such as Kathakali drama or Ottan Tullal, are very common. When a family can ill-afford to celebrate the ceremony on any grand scale, the girls are taken to the nearest temple, or to the illam of a Nambūdri, if they happen to belong to sub-divisions attached to illams, and the tāli is tied with little or no feasting and merriment. In the northern taluks, the very poor people sometimes tie the tāli before the Trikkakkarappan on the Tiruvonam day.”

An interesting account of the tāli-kettu ceremony is given by Duarte Barbosa, who writes as follows.83 “After they are ten or twelve years old or more, their mothers perform a marriage ceremony for them in this manner. They advise the relations and friends that they may come to do honour to their daughters, and they beg some of their relations and friends to marry these daughters, and they do so. It must be said that they have some gold jewel made, which will contain half a ducat of gold, a little shorter than the tag of lace, with a hole in the middle passing through it, and they string it on a thread of white silk; and the mother of the girl stands with her daughter very much dressed out, and entertaining her with music and singing, and a number of people.

And this relation or friend of hers comes with much earnestness, and there performs the ceremony of marriage, as though he married her, and they throw a gold chain round the necks of both of them together, and he puts the above mentioned jewel round her neck, which she always has to wear as a sign that she may now do what she pleases. And the bridegroom leaves her and goes away without touching her nor more to say to her on account of being her relation; and, if he is not so, he may remain with her if he wish it, but he is not bound to do so if he do not desire it. And from that time forward the mother goes begging some young men to deflower the girl, for among themselves they hold it an unclean thing and almost a disgrace to deflower women.”

The tāli-kettu ceremony is referred to by Kerr, who, in his translation of Castaneda, states that “these sisters of the Zamorin, and other kings of Malabar, have handsome allowances to live upon; and, when any of them reaches the age of ten, their kindred send for a young man of the Nāyar caste out of the kingdom, and give him presents to induce him to initiate the young virgin; after which he hangs a jewel round her neck, which she wears all the rest of her life, as a token that she is now at liberty to dispose of herself to anyone she pleases as long as she lives.”

The opinion was expressed by Mr. (now Sir Henry) Winterbotham, one of the Malabar Marriage Commissioners, that the Brāhman tāli-tier was a relic of the time when the Nambūtiris were entitled to the first fruits, and it was considered the high privilege of every Nāyar maid to be introduced by them to womanhood. In this connection, reference may be made to Hamilton’s ‘New Account of the East Indies’, where it is stated that “when the Zamorin marries, he must not cohabit with his bride till the Nambūdri, or chief priest, has enjoyed her, and he, if he pleases, may have three nights of her company, because the first fruits of her nuptials must be an holy oblation to the god she worships. And some of the nobles are so complaisant as to allow the clergy the same tribute, but the common people cannot have that compliment paid to them, but are forced to supply the priests’ places themselves.”

Of those who gave evidence before the Malabar Commission, some thought the tāli-kettu was a marriage, some not. Others called it a mock marriage, a formal marriage, a sham marriage, a fictitious marriage, a marriage sacrament, the preliminary part of marriage, a meaningless ceremony, an empty form, a ridiculous farce, an incongruous custom, a waste of money, and a device for becoming involved in debt. “While,” the report states, “a small minority of strict conservatives still maintain that the tāli-kettu is a real marriage intended to confer on the bridegroom a right to cohabit with the bride, an immense majority describe it as a fictitious marriage, the origin of which they are at a loss to explain. And another large section tender the explanation accepted by our President (Sir T. Muttusami Aiyar) that, in some way or other, it is an essential caste observance preliminary to the forming of sexual relations.” In a recent note, Mr. K. Kannan Nāyar writes84:

“Almost every Nāyar officer in Government employ, when applying for leave on account of the kettukalliānam of his daughter or niece, states in his application that he has to attend to the ‘marriage’ of the girl. The ceremony is generally mentioned as marriage even in the letters of invitation sent by Nāyar gentlemen in these days....

This ceremony is not intended even for the betrothal of the girl to a particular man, but is one instituted under Brāhman influence as an important kriya (sacrament) antecedent to marriage, and intended, as the popular saying indicates, for dubbing the girl with the status of Amma, a woman fit to be married. The saying is Tāli-kettiu Amma āyi, which means a woman has become an Amma when her tali-tying ceremony is over.”

In summing up the evidence collected by him, Mr. L. Moore states85 that it seems to prove beyond all reasonable doubt that “from the sixteenth century at all events, and up to the early portion of the nineteenth century, the relations between the sexes in families governed by marumakkattayam were of as loose a description as it is possible to imagine. The tāli-kettu kalyānam, introduced by the Brāhmans, brought about no improvement, and indeed in all probability made matters much worse by giving a quasi-religious sanction to a fictitious marriage, which bears an unpleasant resemblance to the sham marriage ceremonies performed among certain inferior castes elsewhere as a cloak for prostitution. As years passed, some time about the opening of the nineteenth century, the Kērala Mahatmyam and Keralolpathi were concocted, probably by Nambūdris, and false and pernicious doctrines as to the obligations laid on the Nāyars by divine law to administer to the lust of Nambūdris were disseminated abroad.

The better classes among the Nāyars revolted against the degrading custom thus established, and a custom sprang up especially in North Malabar, of making sambandham a more or less formal contract, approved and sanctioned by the karnavan (senior male) of the tarwad to which the lady belonged, and celebrated with elaborate ceremony under the pudamuri form. That there was nothing analogous to the pudamuri prevalent in Malabar from A.D. 1550 to 1800 may, I think, be fairly presumed from the absence of all allusion to it in the works of the various European writers.” According to Act IV, Madras, 1896, sambandham means an alliance between a man and a woman, by reason of which they in accordance with the custom of the community to which they belong, or either of them belongs, cohabit or intend to cohabit as husband and wife.