Shahabad District, 1908

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

Contents |

Shahabad District

District in the Patna Division of Bengal, lying between 24 31' and 25 46' N, and 83 19' and 84 51' E., with an area of 4,373 square miles. It is bounded on the north by the Districts of Ghazipur and Ballia in the United Provinces and by the Bengal District of Saran ; on the east by Patna and Gaya Districts ; on the south by Palamau ; and on the west by the Districts of Mirzapur and Benares in the United Provinces. The Karamnasa river forms part of the western boundary.

Physical aspects

Shahabad consists of two distinct tracts differing in climate, scenery, and productions. The northern portion, comprising about three- fourths of the whole, presents the ordinary flat aspects. appearance common to the valley of the Ganges in the sub-province of Bihar ; but it has a barer aspect than the trans-Gangetic Districts of Saran, Darbhanga, and MuzafTarpur. This tract is entirely under cultivation, and is dotted over with clumps of trees. The south of the District is occupied by the Kaimur Hills, a branch of the great Vindhyan range. The Son and the Ganges may be called the chief rivers of Shahabad, although neither of them any- where crosses the boundary.

The District lies in the angle formed by the junction of these two rivers, and is watered by several minor streams, all of which rise among the Kaimur Hills and flow northwards towards the Ganges. The most noteworthy of these is the Karamnasa, the accursed stream of Hindu mythology, which rises on the south- ern ridge of the Kaimur plateau, and flows north-west, crossing into Mirzapur District near Kuluha. After a course of 15 miles in that District, it again touches Shahabad, which it separates from Benares ; finally, it falls into the Ganges near Chausa. The Dhoba" or Kao rises on the plateau, and flowing north, forms a fine waterfall and enters the plains at the Tarrachandi pass, 2 miles south-east of Sasaram. Here it bifurcates one branch, the Kudra, turning to the west and ulti- mately joining the Durgautl; while the other, preserving the name of Kao, flows north and falls into the Ganges near Gaighat. The DurgautI rises on the southern ridge of the plateau and, after flowing north for 9 miles, rushes over a precipice 300 feet high into the deep glen of Kadhar Kho \ eventually it joins the Karamnasa. It contains water all the year round, and during the rains boats of i-J- tons burden can sail up-strearn 50 or 60 miles from its mouth. Its chief tributaries are the- Sura, Kora, Gonhua, and Kudra.

The northern portion of the District is covered with alluvium. The Kaimur Hills in the south are formed of limestones, shales, and red sandstones belonging to the Vindhyan system.

Near the Ganges the rice-fields have the usual weeds of such locali- ties. Near villages there are often considerable groves of mangoes and palmyras (Borassus flabellifer)^ some date palms (Phoenix sylvestris\ and numerous isolated examples of Tamarindus and similar more or less useful species. Farther from the river the country is more diversi- fied, and sometimes a dry scrub jungle is met with, the constituent species of which are shrubs of the order of Euphorbiaceae^ Butea and other leguminous trees, species of Ficus^ Sehleichera, Wendlandia^ and Gmelina. The grasses that clothe the drier parts are generally of a coarse character. There are no Government forests, but the northern face of the Kaimur Hills is overgrown with a stunted jungle of various species, while their southern slopes are covered with bamboos.

Large game abounds in the Kaimur Hills. Tigers, bears, and leopards are common; five or six kinds of deer are found; and among other animals wild hog, jackals, hyenas, and foxes are also met with.

Owing to its distance from the sea, Shahabad has greater extremes of climate than the south and east of Bengal. The mean temperature varies from 62 in January to 90 in May, the average maximum rising to 102 in the latter month. Owing to the hot and dry westerly winds which prevail in March and April, the humidity at this season is only 52 per cent. With the approach of the monsoon the humidity steadily increases ; it remains steady at 88 throughout July and August, and then falls to 79 in November. The annual rainfall averages 43 inches,

VOL. XXII. N of which 5-5 fall in June, 11-7 in July, 12-3 in August, and 6-8 in September.

Floods are occasionally caused by the river Son overflowing its banks. In recent times the highest floods occurred in 1876 and 1901 j in the latter year the water rose 1-2 feet above any previously recorded level, and it is stated that the river was at one point 1 7 miles wide. Owing to the cutting of an embankment at Darara by some villagers, the flood found its way into Arrah town and caused con- siderable damage to house property.

History

Shahabad was comprised within the ancient kingdom of Magadha, whose capital was at Rajgir in Patna District, and its general history is outlined in the articles on MAGADHA and BIHAR, in which Magadha was eventually merged. It may be added that, when the country relapsed into anarchy on the decline of the Gupta dynasty, Shahabad came under the sway of a number of petty aboriginal chiefs and had a very small Aryan population. The ruling tribe at this period was the Chero, and the District was till a comparatively recent period in a great degree owned by the Cheros and governed by their chieftains. They were subsequently conquered by Rajput immigrants, and few of them arc now found in Shahabad, though they still number several thousands in the adjoining District of Palamau. Under the Muhauunadans Shahabad formed part of the Sitbah of Bihar, and in the sixteenth century was the scene of part of the .struggles which made Sher Shah emperor of Delhi. Sher Shah, after establishing himself at Chunar in the United Provinces, was engaged on the conquest of Bengal.

In 1537 Humayun advanced against him, and after a siege of six months reduced his fortress of Chunar and marched into Bengal. Sher Shah then shut himself up in Rohtasgdrh, which hti had captured by a stratagem, and made no effort to oppose his advance. Humayun spent six months in dissipation in Bengal ; but then, finding that Sher Shah had cut off his communications and that his brother at Delhi would not come to his assistance, he retraced his steps and was defeated at Chausa near Buxar. Buxar is also famous as the scene of the defeat in 1764 by Sir Hector Munro of Mir Kasim, in the battle which finally won the Lower Provinces of Bengal for the British. Since then the only event of historical interest is the defence of the Judge's house at ARRAH in the Mutiny of 1857.

Among Hindu remains may be mentioned the temple on the MUNDESWARI Hill dating from the sixth or seventh century. The short reign of Sher Shah is still borne witness to by one of the finest specimens of Muhammadan sepulchral architecture, his own tornb at SASARAM, which he originally held as IMS jaglr. His father's tomb in the same town and the tomb of Bakhtyar Khan, near Chainpur, in the Bhabua subdivision, are similar but less imposing.

The small hill fort of SHERGARH, 26 miles south-west of Sasaram, dates from Sher Shah's time, but at ROHTASGARH itself few traces of this period remain ; the palace at this place is attributed to Man Singh, Akbar's Hindu general. Other places of interest in Shahabad are the CHAINPUR fort with several interesting monuments and tombs* Ram- garh with a fort, and Darauti and Baidyanath with ruins attributed to the Savaras or Suars ; MASAR, the Mo-ho-so-lo of Hiuen Tsiang ; TILOTHU, near which are a fine waterfall and a very ancient Chero image ; Patana, once the capital of a Hindu Raja of the Suar tribe ; and Deo-Barunark and Deo-Markandeya, villages which contain several old temples and other remains, including an elaborately carved mono- lith at the former place. The sacred cave of Gupteswar lies in a valley in the Kaimur Hills, 7 or 8 miles from Shergarh.

Population

The population increased from 1,710,471 in 1872 to 1,940,900 in i88r,-and to 2,060,579 in 1891, but fell again to 1,962,696 in 1901. The increase in the first two decades was largely due to the extension of cultivation, owing to the opening of the irrigation canals. The climate of the northern part of the Dis- trict is said to be steadily deteriorating. The surface is so flat and low that there is no outlet for the water which accumulates, while the intro- duction of the canals is said to have raised the water-level and made the drainage even worse than before. Fever began to make its ravages felt in 1879, an d from that time the epidemic grew steadily worse until ,1886, when the District was stigmatized as the worst in Bengal in respect of fever mortality*

At the Census of 1891 a decrease was averted only by a large gain from immigration. From 1892 to 1900 the vital statistics showed an excess of deaths over births amounting to 25,000, and in 1894 the death-rate exceeded 53 per 1,000, After fever, the principal diseases are dysentery, diarrhoea, cholera, and small-pox. Blindness is very common. Plague broke out at Arrah just before the Census of 1901. The number of deaths reported was small, but the alarm which the epidemic created sufficed to drive to their homes most of the tem- porary settlers from other Districts.

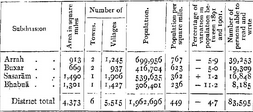

The principal statistics of the Census of 1901 are shown in the table on the next page.

The principal towns are ARRAH, the head-quarters, SASARAM, DUM- RAON, and BUXAR. With the exception of Sasaram, all the towns seem to be decadent, The population is densest in the north and east of the District, on the banks of the Ganges and Son, and decreases rapidly towards the south and south-east, where the Kaimur Hills afford but small space for cultivation. The Bhabua thana^ with i8r persons per square mile, has the scantiest population of any tract in South Bihar. The natives of this District are in demand all over Bengal as zamlndarf peons and club men \ they are especially numerous in Purnea, North Bengal, Dacca, and in and near Calcutta, and a large number find their way to Assam. Many also emigrate to the colonies. The vernacular is the Bhojpurl dialect of Bihari, but the Muhammadans and Kayasths mostly speak Awadhi Hindi. In 1901 Hindus numbered 1,819,641, or no less than 92-7 per cent, of the total, and Musalmans 142,213, or nearly 7-3 per cent.; there were 449 Jains and 375 Christians.

The most numerous castes are Ahirs or Goalas (256,000), Brahmans and Rajputs (each numbering 207,000), Koiris (155,000), Chamars (121,000), Dosadhs (87,000), Babhans (82,000), Kahars (70,000), Kurmis (66,000), Kandus (63,000), and Telis (51,000); and, among Muhammadans, Jolahas (53,000). Agriculture supports 64-8 per cent.- of the population, industries 17-7 per cent., commerce 0-5, and the professions 1-9 per cent.

The only Christian mission is a branch of the German Evangelical Lutheran Mission, whose head-quarters are at Ranch!. The number of native Christians in 1901 was 72.

Agriculture

Clay is the predominating soil, but in parts it is more or less mixed with sand. The clay soils, known as karail, kewal, matiyar^ and u gurmat) are suitable for all kinds of grain, and the level of the land and the possibility of irrigation are here the main factors in determining what crop shall be cultivated. Doras is a rich loam containing both clay and sand, and is suited for sugar-cane, poppy, mustard, and linseed. Sandy soil is known as balmat, and when it is of very loose texture as dkus. The alluvial tract in the north is extensively irrigated by canals and is entirely under cultivation. The low-lying land in the neighbourhood of the Ganges, locally known as kadai, is annually inundated so that rice cannot be grown, but it produces fine cold-season crops. Along the west bank of the Son within about 3 miles from the river the soil is sandy, and requires continuous irrigation to produce good crops* To the west of this the prevalent soil south of the grand trunk road is doras, which is annually flooded and fertilized by the hill streams. In the Sasaram subdivision karail soil is most common and grows excellent rabi crops. The undulating plateau of the Kaimur Hills in the south is unprotected by irrigation and yields poor and precarious crops.

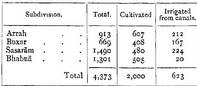

The chief agricultural statistics for 1903-4 are given below, areas being in square miles :

There are altogether about 311 square miles of cultivable waste, statistics for each subdivision not being available ; and it is estimated that 112 square miles are twice cropped.

The staple food-crop of the District is rice, grown on 1,307 square miles, of which 1,112 square miles are under aghani or winter rice. This crop is transplanted in June and July (except in very low lands, where it is sometimes sown broadcast), and the water is retained in the rice-fields by ridges till the middle of September, when it is allowed to drain off. The fields are left to dry for 12 to 14 days, after which the crop again needs water, for which it depends on the hathiya rain, or failing this, on irrigation. These late rains are the most important in the year, as they are required not only to bring the winter crop .

to maturity, but also to provide moisture for the sowing of the rabi crops. BorO) or spring rice, is grown in river-beds and on the edge of marshes ; it is sown in January and February, transplanted after a month, and cut in April and May. Of the other crops of the rainy season, the principal are maize or makaf t marua t jowar, and bajra these are grown on well-drained high lands. The rabi crops con- sist of cereals and pulses. The chief cereals are wheat (188 square miles), barley (81 square miles), and oats. They are sown in October and November, and harvested between the last week of February and the middle of April. The pulses include peas, gram, and linseed ; gram and linseed are grown as a second crop, being sown in the standing aghani rice about a fortnight before it is cut. Other impor- tant crops are poppy (25 square miles) and sugar-cane (54 square miles).

The opening of the Son Canals has resulted in a considerable increase in the cultivated area. An experimental farm is maintained at Dumraon, but even in the adjoining villages the cultivators are slow to profit by its lessons. Little advantage has been taken of the Land Improvement and Agriculturists' Loans Acts, except in the famine years 1896-8, when Rs. 75,000 was advanced under the latter Act.

The cattle are for the most part poor, but good bulls are kept at the Buxar Central jail, and their offspring find a ready sale. Pasture is scarce except in the Kaimur Hills, where numerous herds are sent to graze during the rains. A large cattle fair is held at Barahpur, at which agricultural stock and produce are exhibited for prizes.

The District is served by the SON CANALS system, receiving about ' 80 per cent, of the total quantity of water supplied by it. Wells and ahars^ or reservoirs, are also maintained all over the District for the purposes of irrigation. In 1901 it was estimated that 489 square miles were irrigated from the canals, 364 square miles from wells, and 937 square miles from ahars. The extent to which an artificial water- supply is used depends on the variations in the rainfall; in 1903-4 the area irrigated from the Government canals was 623 square miles,

Red sandstone from the Kaimur Hills is used extensively for build- ing purposes, for which it is admirably adapted. Limestone, which is obtained from the same locality, is commonly dark grey or blackish, and burns into a very good white lime. Kankar or nodular lime- stone is found in almost all parts of the plains, and especially in the beds of rivers and along the banks of the Son ; it is used for metalling roads and is also burnt to make lime. A small quantity of alum was formerly manufactured in the area north of Rohtasgarh from slates be- longing to the Kaimur group of the Vindhyan series. Copperas or iron sulphate is found in the same region.

Trade and Communication

Sugar is manufactured throughout the District, the principal centres of the industry being at Nasriganj and Jagdispur. Iron sugar-cane mills, manufactured at Bihiya, are now in general use communions. over a S reat P art of Northern India - Carpets and pottery are made at Sasaram ; the speciality of the pottery consists in its being painted with lac and overlaid with mercury and gilt. Blankets and cotton cloth are woven throughout the District. A small quantity of hand-made paper is produced at Hariharganj. Saltpetre is manufactured in small quantities, the out-turn in 1903-4 being 5,000 maunds.

The principal imports are rice, gram, and other food-grains from the neighbouring Districts, European cotton piece-goods and kerosene oil from Calcutta, and coal and coke from Hazaribagh and Palamau. The exports include wheat, gram, pulses, and oilseeds, chiefly to Calcutta, and raw sugar and gur to the United Provinces and elsewhere. The chief centres of trade are Arrah, Dumraon, Buxar, and Chausa on the East Indian Railway, Sasaram and Dehri on the Mughal Sarai-Gaya branch, and Nasriganj on the Son. The main lines of communication are the railways, the Ganges and Son rivers, and the Son Canals, to which goods are brought by bullock carts and pack-bullocks.

The main line of the East Indian Railway runs for 60 miles from east to west through the north of the District, and the Mughal Sarai- Gaya section opened in 1900 traverses the south. In addition to 58 miles of the grand trunk road from Calcutta to Benares, which passes through Dehri-on-Son, Sasarain, and Jahanabad, and is main- tained from Provincial funds, the District contains 186 miles of metalled and 532 miles of unmetalled roads under the control of the District board; there are also 1,218 miles of village tracks. The principal local roads are those which connect Arrah with Buxar and Sasaram. Feeder roads connect the main roads with the stations on the railway and with the principal places on the rivers.

The Ganges is navigable throughout the year, and a tri-weekly steamer service for passengers and goods traffic plies as far as Benares, touching at Buxar and Chausa in this District. Navigation on the Son is intermittent and of little commercial importance. In the dry season the small depth of water prevents boats of more than 20 maunds proceeding up-stream, while in the rains the violent floods greatly impede navigation, though boats of 500 or 600 rnaunds occasionally sail up. Of the other rivers the Karamnasa, the Dhoba, or Kao, the DurgautI, and the Sura are navigable only during the rainy season. The main canals of the Son Canals system are navigable; a bi- weekly service of steamers runs from Dehrl to Arrah. But here, as elsewhere, most of the water-borne traffic is carried in country boats, some of which have a capacity of as much as 1,000 maunds. The canal-borne traffic used to be considerable, but has suffered greatly from competition with the Mughal Sarai-Gaya branch of the East Indian Railway. The only ferries of any importance are those across the Ganges.

Famine

The District has frequently suffered from famine. The famine of 1866, having been preceded by two years of bad harvests, caused great distress. The Government relief measures were supplemented , by private liberality, but 3,161 deaths from starvation were reported. There was another, but less severe, famine in 1869. In 1873 more than three-fourths of the rice crop was destroyed by very heavy floods and the subsequent complete absence of rain ; the loss would have been even greater had not the Son water been turned into the unfinished canals and freely distributed. Relief works, in the shape of road repairs, were opened in December, and a sum of i'i8 lakhs was spent in wages, in addition to Rs. 30,000 paid to non-workers, and Rs. 1,600 advanced to cultivators for the purchase of seed-grain. In the famine of 1896-7 the distressed area comprised the whole of the Bhabua and the southern portion of the Sasaram sub- division. Relief works were started in October, 1896, and were not finally closed till July, 1897, during which period 560,031 days' wages were paid to adult males employed on piece-work, and 175,105 to those on a daily wage, the aggregate payments amounting to Rs. 74,000.

Gratuitous relief by means of grain doles was also given, and poor- houses and kitchens were opened, The cost of gratuitous relief was rather less than 2 lakhs, and the total cost of the famine operations was 3-36 lakhs, of which Rs. 30,000 was paid from District and the balance from Provincial funds.

Administration

For administrative purposes the District is divided into 4 subdivi- sions, with head-quarters at ARRAH, BUXAR, S AS ARAM, and BHABUA. Subordinate to the District Magistrate-Collector at A ministration, Arrahj ^ District head-quarters, is a staff consist- ing of an Assistant Magistrate-Collector, six Deputy-Magistrate- Collec- tors, and two Sub-Deputy-Collectors. The subdivisions of Sasaram and Buxar are each in the charge of an Assistant Collector aided by a Sub-Deputy-Collector, and the Bhabua subdivision is under a Deputy- Magistrate-Collector. The Executive Engineer of the Arrah division is stationed at Arrah ; an Assistant Engineer resides at Koath and the Executive Engineer of the Buxar division at Buxar.

The permanent civil judicial staff consists of a District Judge, who is also Sessions Judge, two Subordinate Judges and three Munsifs at Arrah, one Munsif at Sasaram and another at Buxar. For the disposal of criminal work, there are the courts of the Sessions Judge, District Magistrate, and the above-mentioned Assistant, Deputy, and Sub- Deputy-Magistrates. The District was formerly notorious for the number of its dacoits and for the boldness of their depredations ; but this crime is no longer common. The crimes now most preva- lent are burglary, cattle-theft, and rioting, the last being due to disputes about land and irrigation.

During the reign of Akbar, Shahabad formed a part of sarkar Rohtas, lying for the most part between the rivers Son and Karamnasa. Half of it, comprising the zamindari of Bhojpur, was subsequently formed into a separate sarkar called Shahabad. The land revenue demand of these two sarkars, which was fixed at 10-22 lakhs by Todar Mai in 1582, had risen to 13-66 lakhs at the time of the settlement under All Vardi Khan in 1750, but it had again fallen to 10-38 lakhs at the time of the Decennial Settlement which was concluded in 1790 and declared to be permanent in 1793. The demand gradually rose to 13-55 ^ ns in 1843 and 16-72 lakhs in 1862, the increase being due to the revenue survey which took place in 1846.

In 1903-4 the total demand was 17-27 lakhs payable by 10,147 estates, of which 9,463 with a demand of 14-98 lakhs were permanently settled, 544 with a demand of 1-38 lakhs were temporarily settled, while the remainder were held direct by Govern- merit. The incidence of land revenue is R. 0-13-9 P er cultivated acre, being about 22 per cent, of the estimated rental. Rents vary with the class of soil, and for very good land suitable for poppy as much as Rs. 30 per acre is occasionally paid. Rent is generally paid in kind, especially in the Bhabua and Sasaram subdivisions. The average hold- ing of a ryot is estimated at 5f acres. The only unusual tenure is the guzastha, which connotes not only a right to hold at a fixed rate in perpetuity but an hereditary and transferable interest in the land. The true guzasthd tenure is confined mainly to the Bhojpur pargana, but the term is used elsewhere to indicate the existence of occupancy rights. The following table shows the collections of land revenue and total revenue (principal heads only), in thousands of rupees :

Outside the municipalities of ARRAH, JAGDISPUR, BUXAR, DUMRAON,

BHABUA, and SASARAM, local affairs are managed by the District board

with subordinate local boards in each subdivision. In 1903-4 its

income was Rs. 2,63,000, of which Rs. 2,03,000 was derived from

rates ; and the expenditure was Rs. 2,89,000, the chief item being

Rs. 2,15,000 expended on public works.

In 1903 the District contained n police stations and 18 outposts. The force subordinate to the District Superintendent in that year consisted of 4 inspectors, 43 sub-inspectors, 46 head constables, and 526 constables; there was also a rural police force of 301 daffaddrs and 4,254 chauklddrs. In addition to the District jail at Arrah with accommodation for 278 prisoners, there is a Central jail at Buxar with accommodation for 1,391, while subsidiary jails at Sasaram, Buxar, and Bhabua can hold 69. The prisoners in the Central jail are chiefly employed in weaving and tent-making.

Of the population in 1901, 4-3 per cent. (8-6 males and 0-3 females) could read and write. The total number of pupils under instruction fell from 20,883 in 1883-4 to 16,922 in 1892-3, but increased again to 23,032 in 1900-1. In 1903-4, 26,218 boys and 445 girls were at school, being respectively 18-6 and 0-28 per cent, of the children of school-going age. The number of educational institutions, public and private, in that year was 1,004, including 23 secondary, 623 primary, and 358 special schools. Two small schools for aborigines are maintained at Rehal and Dahar. The expenditure on education was 1*36 lakhs, of which Rs. 17,000 was paid from Provincial funds, Rs. 40,000 from District funds, Rs. 3,000 from municipal funds, and Rs. 59,000 from fees.

In 1903 the District contained 12 dispensaries, of which 7 had accom- modation for 115 in-patients. The cases of 81,000 out-patients and 2,300 in-patients were treated, and 8,000 operations were performed. The expenditure was Rs. 35,000, of which Rs. 5,000 was derived from Government contributions, Rs. 7,000 from Local and Rs. 10,000 from municipal funds, and Rs. 10,000 from subscriptions.

Vaccination is compulsory only in municipal areas. In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 48,000, or 25-8 per 1,000 of the population.

[L. S. S. O'Malley, District Gazetteer (Calcutta, 1906) ; M. Martin (Buchanan-Hamilton), Eastern India, vol. i (1838).]