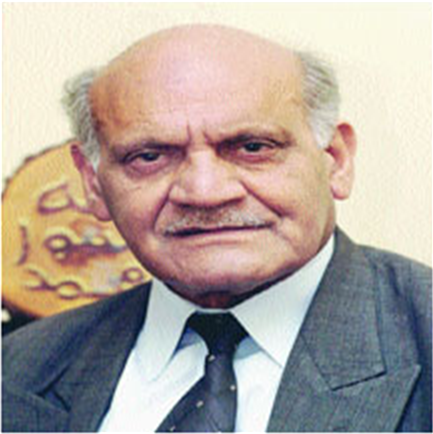

Anwar Masood

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Anwar Masood

Humour is like a cloud that thunders and flashes before bursting into rain

—Anwar Masood

By Naseer Ahmad

Selected and collected in Ik Dareecha, ik chiragh, Anwar Masood’s serious poetry, with vivid images and simple words, is a delightful contribution to Urdu literature by a poet known mostly for his humourous verses, provoking peals of laughter at poetry recitals (mushairas).

Chiqen giri theen dareechon mein charsoo Anwar/ Nazar jhuka kay na chaltay tau aur kiya kartay

(The curtains were drawn closed in the windows everywhere. So I had no choice but to walk by with eyes downcast.)

Another couplet of his says: Raat bhar teiz hawa chalti rahi hai Anwar/ Phool shakhon say giray hoangay na janay kitnay

(A strong wind blew the whole night. I fear countless blooms must have snapped off the twigs.)

Writing in Urdu, Punjabi and Persian, Anwar’s prose is also lucid. His Farsi adab kay chand goshay has been acclaimed by many noted writers and critics. Baat say baat is a collection of his radio columns, written in a light manner to highlight various social issues. In all, he has 11 books to his credit. But what he calls his “most important work” is yet to be published and that is his Urdu translation of Mian Mohammad Bakhsh’s Saiful Muluk. He admits that the classic fairytale, rendered in enchanting poetry, has been translated by Zameer Jaafri and Shafi Aqeel before him. “Zameer Jaafri has mainly focused on events rather than taking each and every couplet into account. Shafi Aqeel’s translation is good, but he too has skipped many verses. I have translated all the 10,000 couplets,” says Anwar, a great admirer of the saint-poet of Kashmir and his craft. Most of his books are so popular that they have run into multiple editions, Mela akhian da, for instance, has run into its 42nd edition. This was his first book, published in 1974. And that’s why he says, unlike other writers and poets, he has no complaint against his publisher as “the gentleman pays me royalty regularly”.

When I remind him during an interview that his serious work has been eclipsed by his immensely popular humour poetry, both in Urdu and Punjabi, he says, “It’s true though at mushairas abroad I’m introduced with my serious poetry. He says poets such as Nazir Akbarabadi, Akbar Allahabadi, Zameer Jaafri and Prof Inayat Ali Khan have also written good serious poetry, but they are also known for their humour poetry. Once I had put this question to Zameer Jaafri and he said ‘Whatever the people have accepted, we should be glad and thankful for it’.”He says that because of national and international gloomy conditions, people are so stressed that they long for something light to help them forget their worries. “It is natural that they should demand humorous poetry more than serious poetry at mushairas. Actually, laughter is another facet of grieving. Laughter and cries are inter-related. Sometimes people laugh only to suppress their cry.”

Continuing, he quotes his own couplet: “Baray numnaak say hotay hein Anwar qehqahay teray/ Koi deewar-i-girya hai teray ashaar kay peechhay

(Your laughs are tearstained, O Anwar. Your verses seem to have sprung from a wailing wall.)

“Light-hearted verses are like maze corn, when it burns, it laughs (pops up). A cloud laughs (flashes and thunders) before bursting into tears (rain).” A deeply religious man, he believes that making people smile is also an act of piety.

Anwar Masood began writing poetry when he was a young boy, growing up in the literary atmosphere of Gujrat. “At that time Gujrat was the hub of literary activities. My Taya ji (uncle) was very active in organising mushairas and even my naani (grandmother), Karram Bibi, had a poetry collection to her credit.”

And he has another reason to become a humour poet. “I belong to the mohalla in Gujrat where Imam Deen had lived his life,” famous for his satirical poems collected in Baang-i-Duhal, though he claims that the indiscreet publisher of the book had included a couple of poems not written by Imam Deen. “My Juma Bazaar has been attributed to him. If the publisher had any sense, he would have known that there was no concept of Juma bazaars in Imam Deen’s days,” says Anwar.

When I say that he is probably the most popular humour poet, particularly in Punjabi, he says, “No, no. I have never made such a claim. We have so many good humour poets, mostly concentrated in Islamabad and in Karachi.” He names them and is careful not to miss out even a single name worth naming.

Green campaigner

His Meili, meili dhoop makes him a rare kind of environmental activist. Appropriately illustrated, this book contains mostly short and crisp poems highlighting various environmental issues in a pleasant way. He has hardly left any aspect of the environment that he has not commented upon -- water contamination, air pollution, noise pollution, smoking, spitting paan juice, and the need to grow more and more trees and keep the environment clean. In a parody, he hums:

Phephron ko dhuain say bharta hoon/ Jab teray shehr say guzarta hoon

(Whenever I happen to pass through your city, I inflate my lungs with fumes.)

He also calls pop music a paap (sin) because of its noise-polluting effects. Amjad Islam Amjad seems right when he says, in his foreword to Meili, meili dhoop, that this is the only poetry collection in the world on the environment.

Anwar laments that the successive generations have gradually lost interest in Persian, depriving themselves of the joy of Persian poetry, particularly that of Ghalib and Allama Iqbal, whose major works are in Persian.

His wife, an Urdu-speaking woman, was his classmate. They both taught Persian in different colleges and became life partners. They have two daughters and three sons, all grown up, happily married and well settled. The elder daughter is also a professor of the Persian language. Ammar Masood, his middle son, hosts a cultural programme on a TV channel. Living a life of leisure in Islamabad, these days he doesn’t “do much reading and writing”, as he puts it. But he daily contributes a quatrain to an Urdu newspaper.

His books are: Baat say baat , Mela akhiyan da, Guncha phir laga khilnay, Hun ki kariay, Shakh-i-Tabassum, Ik dareecha, ik chiragh, Meli meli dhoop, Farsi adab kay chand goshay, Qataa kalami, Taqreeb and Darpesh.