Economic Reforms: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

How the reforms unfolded

Trade policy

Surojit Gupta, July 24, 2021: The Times of India

In an interview with TOI, Montek Singh Ahluwalia recalls how the government moved nimbly to make fundamental structural changes, with PMO not questioning the experts. Excerpts:

What do you think led to 1991’s historic decisions — political will or the reality of the economic crisis?

The crisis was clearly an important factor. We were in a desperate situation, with the foreign exchange reserves having more or less run out. The government outlined a two-part agenda. One was to stabilise the economy, and the other to introduce structural reforms, to transit to a higher rate of growth.

The stabilisation part was conventional: reducing the deficit and bringing in the IMF and World Bank to provide funds that would see the economy through a couple of years as stabilisation took effect. However, the decision to bring in reforms was innovative. It cannot be explained by the crisis, or the need to approach the IMF or World Bank, because the reforms went much beyond what those institutions were pressing for. In any case, the crisis was over in 1993…(but) the fact that the reforms continued showed the government was keen on the reforms independent of the crisis.

What’s your standout memory of 1991?

My favourite incident relates to the speed with which we were able to bring about changes in the trade policy in 1991. When Manmohan Singh announced the second devaluation on June 3, he wanted to abolish cash compensatory support (which was given to exporters as an incentive) from June 4 onwards. He asked me to brief minister of state for commerce P Chidambaram on the rationale for it. I did so, but also said we should try to persuade Singh to agree to an accelerated announcement of our proposals for trade liberalisation, including Eximscrip that was aimed at replacing import licences.

We went across to the finance minister’s office and he readily saw the merit of our proposal, overruled his officials who were not in favour, and asked us to come back with a written proposal, “on file” as they say in government, so we could get the Prime Minister to approve. We did that in a few hours and we all went to see Prime Minister Narasimha Rao at about 7pm. After Chidambaram explained our proposal, the PM asked Manmohan Singh whether he agreed. Singh said he had signed the file, at which Rao took the file and signed it, and it was done. There was no examination of the proposal by the PMO.

The whole process of abolishing import controls and moving to marketbased methods of allocating imports, with an ultimate shift to a marketbased exchange rate, was done in the space of eight hours.

Do you think the appetite for reforms has increased among politicians?

If you judge “appetite” by the acceptability of slogans, one could say there is now much greater acceptability of the notion that economic dynamism will be led by the private sector and that the government must not get into areas where the private sector can do a good job. But there are many areas where we see very little progress. Reforms of the land market are proving extremely difficult. Reforms in the labour market are also going slowly. I think the same is true of banking reforms.

We are now at a stage where the reforms we need are much more complex and their benefits will become evident only after many years. Education, for example, is an area where it will take 10 years for reforms introduced now to show up in terms of improved quality of the labour force.

Another problem is that most of our public discussion of reforms focuses on what the central government should do, but water, electricity distribution and health are critical areas which are all in the state sector. If you check what politicians are saying in state elections you will see that it does not reflect an awareness of the need for reforms.

Economic reforms reduced poverty but the Covid pandemic has eroded the gains. What do you think needs to be done now?

We have to act on two fronts. One, to do what we can during the pandemic to extend support to the poor, and the various measures taken for this are all in the right direction. This must be accompanied by concerted efforts to ensure the quickest possible recovery.

Unless we experience another setback in the form of a third wave, the economy will recover in the course of the year and by the start of the next year we will be back where we were in 2019-20. The most important thing to achieve this outcome is a successful vaccination strategy.

This will not by itself offset the negative effects of the pandemic on the poor because the informal sector has been hit much harder, and to that extent even if the economy gets back to the 2019-20 level the poor will still be worse off than they were in 2019-20.

All we can do is focus on ensuring healthy post-pandemic growth from 2022-23 onwards. If the economy only grows at the tepid pre-pandemic rate of a little over 4% or even 5% there is little hope of making a dent in poverty. We need to aim for 7% growth at least.

Devaluation

Surojit Gupta, July 24, 2021: The Times of India

From: Surojit Gupta, July 24, 2021: The Times of India

From: Surojit Gupta, July 24, 2021: The Times of India

From: Surojit Gupta, July 24, 2021: The Times of India

‘Hop, Skip and Jump was code word for devaluation’

C Rangarajan, who served as RBI governor and chairman of PM’s economic advisory council, recounts the anxiety in the lead-up to the actual measures in an interview with TOI. Excerpts:

There were decisions that the RBI took in 1991 which added to the reforms momentum. Could you identify the major ones and how they have fared?

RBI and I were deeply involved and associated with the reforms. From the decision to devalue the rupee to reforms in the monetary, banking and foreign exchange sectors, changes we introduced have stood the test of time.

The most important change was the phasing out of the system of the issue of ad hoc treasury bills by the government to the RBI and thus bringing to an end the automatic monetisation of fiscal deficit. This may indeed be considered as the first step towards giving autonomy to the Reserve Bank of India in relation to the conduct of monetary policy.

In all the areas, the initial changes were followed up by many other actions, all in the same spirit of liberalisation. Since 1991, we have had a comfortable balance of payments situation. The growth rate of the economy had also picked up to a much higher level, even though the recent decline in growth rate is a matter of concern and rethinking.

When did you learn about the historic measures?

I was part of the decision-making process. In adopting the various measures, we knew we were taking a risk. However, we felt these were needed and were confident we would succeed.

Were policymakers anxious about the measures?

I have written about the tension and anxiety while going through the two stage devaluation. The decision to have it in two stages and entrusting it to RBI were novel features. The code word for the exercise was ‘Hop, Skip and Jump’. The shipping of gold which in fact preceded reforms had its own anxious moments when the bullion van carrying gold to the airport had to stop, of course very briefly in between, because of some trouble.

What are the areas that the government needs to focus on in the year ahead?

The reform agenda of 1991 constituted a paradigm shift. Today we don’t need a paradigm shift. We need to look at individual sectors and see which one needs reforms in terms of creating a competitive environment and improving efficiency. Power sector, the financial system, governance and even agricultural marketing need reforms. But we need a lot more discussion and consensus building. Timing and sequencing are also critically important. For example, labour reforms are best introduced when the economy is on the upswing. Looking at the recent discussions on agricultural marketing reforms, the best course of action now may be to leave these measures to each state to decide whether they want these legislations or not. That will set the stage for experimental economics and farmers themselves will be able to see the best possible solution for different crops and conditions.

Some years ago there was talk about India becoming a $5 trillion economy. We are today a $2.7 trillion economy. To reach the goal of $5 trillion, India needs to grow at 9% per annum for at least five years.

The impact

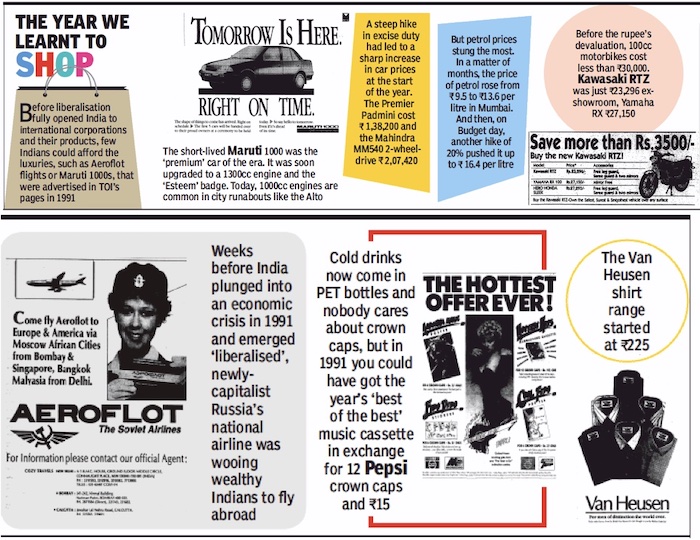

Indian consumers in 1991

From: July 24, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Indian consumers in 1991

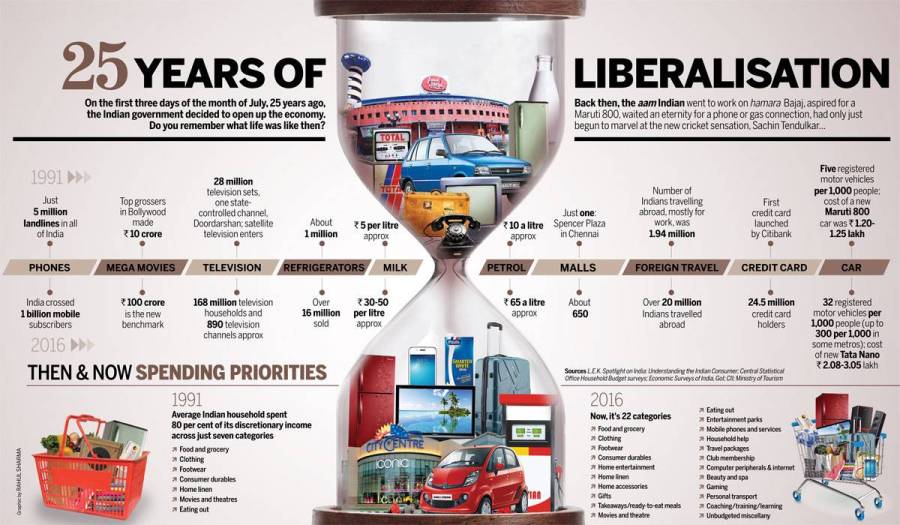

1991-2016

Damayanti Datta , 25 years of liberalization “India Today” 13/7/2016

“India Today”

See graphic

25 years of liberalisation

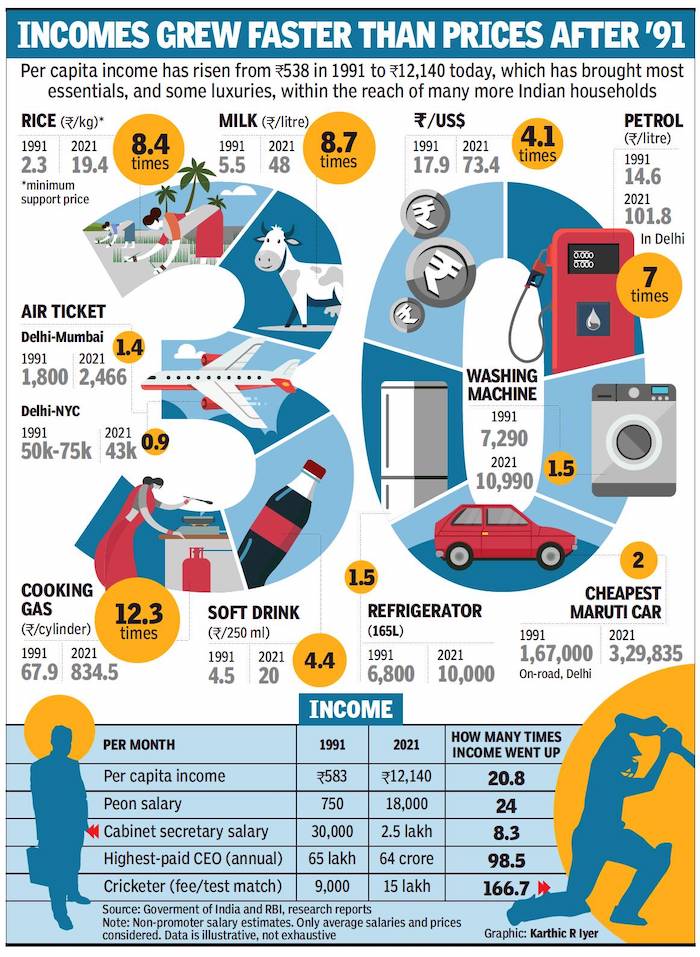

1991-2021

From: July 24, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

The impact of the economic reforms, 1991-2021.

Impact on politics, society

Renuka Bisht & Jiby Kattakayam, July 26, 2021: The Times of India

From: Renuka Bisht & Jiby Kattakayam, July 26, 2021: The Times of India

Perhaps the most symbolically powerful impact of reforms, which began in 1991, on Indian politics was the absence of the word ‘socialism’ from Congress’s 1996 manifesto.

The 30 years from 1991 have seen a dramatic transformation of Indian politics, much of it a result of forces unleashed by new economic policies.

To begin with, the number of successful political parties jumped. BJP, Shiv Sena, BSP, SP and RJD all formed their first governments in the 90s. As the number of parties in Lok Sabha went from 25 to 40 between 1991-96, the theory was also that politics would fractionalise endlessly. That proved false. We pick here some of the defining changes of the last three decades.

CMs on the global stage: Economic liberalisation enabled CMs to don industry-friendly avatars. As Table 1 shows, individual states could woo more investment during 1991-2001 than all of India the decade before.

Karnataka’s tax concessions and incentives spurred the IT industry’s growth there. Andhra Pradesh CM Chandrababu Naidu strode in reformist colours at the global arena, even founding the satellite township of Cyberabad/Hitec City.

Narendra Modi ascended to the national stage through Vibrant Gujarat summits which no CM could have facilitated with the pre-1991 curbs on investment and industrial licensing. Today’s powerful opposition CMs owe their rise in part to those changes 30 years back.

Bye GoI monopolies: Breaking erstwhile PSU-run monopolies gave states like Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand a new lease of life, equipping CMs to undertake development.

Here’s an example. In its 1990-91 budget, Odisha was hoping for a measly Rs 8 crore additional royalty from minerals extracted by GoI. By 2019-20 the state’s mining revenues grew from 2.8% to a whopping 75% of total non-tax revenues, coming to Rs 11,019 crore.

States’ ranking: In 1990-91, Maharashtra, UP, Bengal, undivided AP and TN in that order had the biggest state economies. Cut to 2018-19, the pecking order is Maharashtra, UP, TN, Karnataka and Gujarat.

In more instructive per capita terms, Delhi, Punjab, Maharashtra, Haryana and Gujarat led in affluence among big states in 1990-91, but in 2018-19, Punjab, Maharashtra and Gujarat dropped out, while Karnataka, Telangana and Kerala made their way in. Punjab’s fate highlights the cost of not doing farm reforms.

If you factor in UP’s massive population and Delhi’s melting pot, clearly the west and the south have put the north and the east behind.

Food then, jobs now: In the 1971 post-poll Lokniti-CSDS survey, when asked about the major problems facing the country, 25% respondents give top billing to ‘food and clothing’. By 2019 only 0.3% do the same for ‘hunger, starvation, lack of food’. To no one’s surprise, ‘lack of jobs, unemployment’ is now identified as the most important issue. Another dramatic transformation: In 1971, 25% of those surveyed identified bank nationalisation as their most-liked policy. But today the Union finance secretary can comfortably say that only a bare minimum public sector banks will eventually remain – even if the wait for privatisation, plus overall reforms upgrade, feels like waiting for Godot.

Prosperity’s children: Nineties were the first decade, especially in north India, in which a significant proportion of Dalits were able to exercise their franchise, another clear case of how intimately political and economic empowerment are tied. The turnout gap has declined not just between reserved and unreserved constituencies, but across many social groups. From a 10 percentage points chasm in 1991, women’s turnout is now almost at par with men’s. That their issues get a louder hearing is directly tied to them voting more.

In the past half-decade the number of voters self-identifying as ‘middle class’ has grown from 24% to 56%. And ADR estimates that the share of crorepati Lok Sabha MPs and MLAs has grown to 88% and 78%, respectively. Prosperity is now creed No 1 in once Gandhian India.

Political competition Up, Down: India’s best economic growth phase coincided with a lot of competitive politics. But as growth has slowed, so has political competition. One metric of competition is the average margin of victory in general elections (Table 2), which kept declining after 1991, until 2009. By 2019, the margin had widened to the highest level since 1984. For the first time in 30 years, the share of winning incumbents has also climbed back to the 1991 level.

Many expected a bold economic renewal following such great concentration of political power. That chapter is waiting to be written. But a 1996 Congress slogan reminds why it must be written: “Every rupee earned from reforms is a rupee gained for development.”

B

From: July 26, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

How reforms democratised Dalal Street, 2021

The stock market, 1993-2021

From: July 24, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

The Indian stock market, 1993-2021

Reforms and politics

Dec 18 2014

Political parties have been discussing two key economic policy issues -insurance and the goods and services tax (GST) -for over a decade.Both bills are seen to be critical for improving investor sentiment and efficiency in the economy. When the Congress was in power, the BJP erected roadblocks. With a change in seating arrangement in Parliament, the roles reversed -the BJP is now pushing for these two critical reforms but the Opposition is putting up roadblocks.