Chinese cuisine in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The Indianisation of Chinese food

An overview

Anoothi Vishal, June 21, 2020: The Times of India

From: Anoothi Vishal, June 21, 2020: The Times of India

Chinese is India’s most popular “foreign” cuisine — except that the food most Indians eat and love is not foreign at all! Indian-Chinese has been a legit genre since the 1970s at the very least; though much before that, in Kolkata, experiments in fusion between the cooking of second or third generation Hakka immigrants and Indian ingredients were already taking place.

Despite what a minister said recently about boycotting Chinese food, you don’t have to be a gobhi Manchurian, Chinjabi or karipatta chowmein fan to know that what you are eating is definitely Indian, and virtually unrecognisable in China.

Even at modern restaurants tomtoming “authenticity”, the chef, ingredients and food are all likely to be very desi. “There are hardly any expat chefs in Indian restaurants that serve Chinese or pan-Asian cuisines. Even, internationally, it is Filipino chefs who cook American-Chinese. In India, we have many cooks from the northeast,” points out chef Vikramjit Roy, who specialises in Asian cuisines.

He adds that dishes like chongquin chicken (a Sichuan-style dish, with red chillies and sichuan pepper corn) that you may find in top Indian restaurants are just approximations of Chinese food. “Your mouth will burn if you eat the dish in Chongquin,” he says.

Here, it is an entirely different entity not just because it is localised to suit our palates but also because of the local ingredients restaurants invariably use such as Kashmiri red chillies, triphal which is Sichuan pepper’s sister spice, and locally made soy. “You cannot use Chinese products because these are not vegetarian and Indian audiences don’t like those flavours,” says Saurabh Khanijo, owner of the popular Kylin brand of restaurants in the NCR. In fact, made in India products such as those by Cremica are preferred by many establishments because of suitability to local tastes as well as lower prices.

Stock, rice wine, chilli oil, “fishy products”, strong fermented smells — all these fundamentals of different regional Chinese cuisines are automatically ruled out in any Indian kitchen because of customer non-acceptance. Instead, commercial establishments know how to play around with ginger garlic paste, sweet and sour sauces, garam masala and cornflour to serve up popular “Chinese”, including the orange, glutinous American chopsuey that is neither Chinese nor even Indian but an American invention!

Chilli chicken aside, which is a desi not a Hakka dish, Kung Pao chicken is another Indianised, imported-from-western kitchens eaten more by foreigners than the Chinese. The sweet, sour, starchy sauce in the dish is hated by the Chinese, who find it “too intense and saucy” according to Anthony Zhao, chef and consultant quoted by CNN Travel.

In 1975, Mumbai restaurateur Nelson Wang, then not quite legendary but already running a successful business catering to the Cricket Club of India, invented chicken manchurian precisely because of local preferences. “Some members asked me to serve kuch naya,” Wang had narrated in an earlier interview, “so I fried the chicken, and tossed it in ginger garlic, soy sauce and some other condiments.” A spicy cornfloured pakora at its basic, the dish has nothing to do with Manchuria.

It heralded the coming of Indian Chinese as a widely popular cuisine in its own right in the subsequent decades with dishes such as chilli chicken, crispy lamb, golden fried prawns and hakka noodles. Restaurants in different parts of the country started fusing even this fusion and came up with subgenres, including the all veg, no oniongarlic Jain Chinese, Chinese dosas and bhel!

Indian Chinese, in fact, is India’s export to many countries around the globe such as the US, Canada, Australia. Consultants and chefs are often sought out to expressly set up Indian-Chinese restaurants. This global spread was aided by the emigration of many Chinese-Indians, second or third generation immigrants, in the aftermath of the last war with China. But memories of India are still alive in their mixed food and languages like Bengali and Hindi. In cities like Toronto, you can find Indian restaurants serving wok and kadhai dishes together without any seeming contradiction, much like in India, where popular Udupi restaurants or dhabas may have hakka noodles with tadka!

It is also important to realise how so many of our iconic Chinese restaurants are owned by Indian families, even if we don’t count the uber successful Mumbai restaurateurs of Chinese descent who are all very much Indian — the Lings, Wangs and Thams, at whose hands all the movers and shakers of society have eaten at landmarks such as Nanking, Ling’s Pavilion, China Garden and even the more recent Foo (that serves ceviche with as much aplomb as chilli chicken).

BarBQ in Kolkata, considered the best for Indian-Chinese, is owned by Rajiv Kothari, whose father set up the restaurant in 1960 as a place for Indian-Chinese-Continental, but expanded the Chinese section on realising the popularity of the cuisine. Till coronavirus struck, it was impossible to bag a table on the weekends without waiting in long queues.

Mainland China that took noodles and fried prawns to the masses in Tier II Bharat is owned by Speciality Restaurants founded by Anjan Chatterjee. It is the only Indian restaurant company in its segment to have gone public.

There is more than garam masala in Indian Chinese!

Noodles

2016: India was world’s no.5 consumer

January 7, 2018: The Times of India

From: January 7, 2018: The Times of India

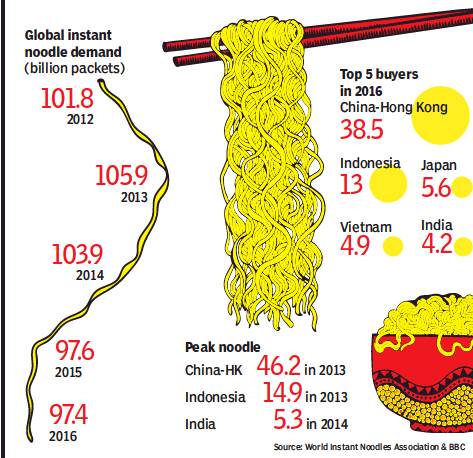

See graphic:

Global instant noodle demand (billion packets), 2012-16

In 2016, India ate less instant noodles than it did back in 2012. Sales in 2015 were far worse because of the Maggi controversy. Globally, sales slid 4.3% between 2012 and 2016. While they stagnated or slid marginally in most other countries, the China-Hong Kong region alone pulled down the world average. Last year, China ate 7.7 billion fewer packets than its peak in 2013, which is almost equal to the combined demand in India and South Korea. Why are the Chinese eating less noodles? Rising living standards means people are demanding more ‘real food’. A big chunk of demand came from rural workers in Chinese cities, but they have been returning home. Finally, ordering proper meals on apps has become cheap, posing competition to 2-minute treats.